Continuing Education Activity

Ancylostoma duodenale, the human hookworm, is the most common parasitic infection in countries with poor access to adequate water, sanitation, and hygiene. Anclyostoma duodenale along with other soil-transmitted helminths (STH) are transmitted through contact with contaminated soil. This activity reviews the pathophysiology, presentation, and diagnosis of ancylostoma and stresses the role of the interprofessional team in the care of patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the pathophysiology of ancylostoma infection.

- Review the presentation of a patient with ancylostoma infection.

- Outline the treatment and management options available for ancylostoma.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and outcomes in patients with ancylostoma infection.

Introduction

Ancylostoma duodenale, the human hookworm, is the most common parasitic infection in countries with poor access to adequate water, sanitation, and hygiene. A. duodenale along with other soil-transmitted helminths (STH) are transmitted through contact with contaminated soil. In the last few decades, zoonotic transmission of 3 other Ancylostoma species has been documented. In these cases, the transmission occurred from domesticated animals to humans.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

A. duodenale as well as, Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma caninum, and Ancylostoma ceylanicum, are anthropophilic human hookworms transmitted from infected soil and transmitted via contact with domesticated animals, such as dogs and cats which are the definitive host of these species. A. duodenale and A. ceylanicum cause intestinal infections with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, anemia, and physical and cognitive impairment. Moreover, A. duodenale pulmonary symptoms can occur in infected humans. Furthermore, all Ancylostoma species can cause creeping skin eruption called cutaneous larva migrans (CLM). Although it is rare, eosinophilic enteritis may occur due to A. caninum infection.[5][6][7]

Epidemiology

It is estimated that more than 1.5 billion people worldwide are at risk for infection with Ancylostoma and other STH. Half of the infections occur in Asia and the Pacific where tropical climate, overcrowded population, poor hygiene, and poor sanitation are present. Ancylostoma, along with the other hookworms, cause more disability than mortality. Hookworm-associated malnutrition and anemia account for the loss of up to 4.1 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALY) annually. The highest at-risk population to contract Ancylostoma infections are the pre-school and school-aged children and travelers who returned from tropical countries. Additionally, people in close contact with dogs and cats are at risk to acquire zoonotic Ancylostoma infection. The incidence of Ancylostoma infection is tied to seasonal distribution where during the summer-autumn period, the incidence is more prevalent. Mixed infections with more than one Ancylostoma species are common in humans.

Pathophysiology

After the eggs of Ancylostoma pass from the stool of their host, the eggs hatch into larvae. In favorable conditions, this occurs in 1 to 2 days. The hatched rhabditiform (non-infective) larvae grow in the feces or soil for 5 to 10 days and mature into filariform (infective) larvae. The filariform larvae can penetrate the human skin via hair follicles, enter the lymphatic system, and migrate to the heart and lungs. In the lungs, the larvae penetrate the pulmonary alveoli, where they ascend from the bronchial tree to the pharynx, can be coughed up, swallowed, and reach the small intestine where they mature into male or female blood-feeding-adults. The mating adult worms can produce thousands of eggs, and the cycle starts over. Furthermore, the filariform larvae can spread via oral ingestion and trans-mammary route where the larvae directly mature in the small intestine or stay dormant in human skeletal musculature. The dormant larvae have been proven responsible for vertical transmission during breastfeeding and are possibly the cause of transplacental infection.

History and Physical

The majority of people who are infected with Ancylostoma are from the endemic areas, or they are travelers who visit endemic areas. Healthcare practitioners should take a careful history, including asking whether patients walk barefoot in endemic areas, have contact with domesticated animals, and inquire about nutritional status and growth of pediatric patients to determine the presence of Ancylostoma infection.

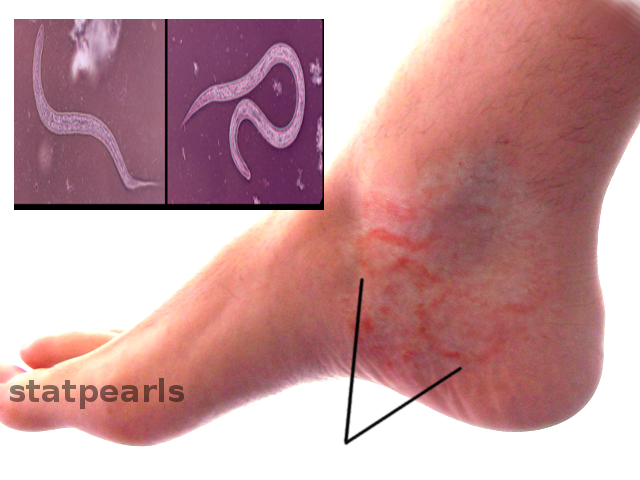

Some people can develop an Ancylostoma infection without any symptoms, while others may have mild to severe symptoms. There are 3 phases: invasion, migration, and establishment in the intestine. During the invasion stage, the filariform larvae penetrate the skin causing local irritation, intense itchiness, and vesicular rash lesions that are called ground itch. In some cases, zoonotic Ancylostoma, for which humans are incompatible hosts, the larvae only penetrate and live at the skin causing the condition known as CLM or creeping eruption. During the CLM, erythema and itchy papules are present. These are followed by linear, serpiginous, and elevated ridges due to the larvae tunneling phenomenon. The CLM lesions usually occur on the upper and lower extremities, although they have been reported on some unusual sites such as the abdomen and penis. However, in rare cases, A. caninum can induce eosinophilic enteritis marked by abdominal pain and peripheral blood eosinophilia.

In the migration phase, larvae escape to the lungs and GI tract and produce organ-related symptoms such as a cough, sore throat, and GI discomfort. Loeffler syndrome, the pulmonary hypersensitive response due to A. duodenale larval migration through lung tissue can occur; although, it is rare. Serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) and peripheral blood eosinophilia are elevated during Loeffler syndrome. If A. duodenale infects a person through the oral route (known as Wakana syndrome), they may experience nausea, vomiting, pharyngeal irritation, cough, dyspnea, and hoarseness.

The most serious symptoms of Ancylostoma infection develop during the last phase when the adult worms establish themselves in the human intestine. Using their buccal capsule and teeth, the adult worms attach to the mucosa and rupture capillaries and arterioles to feed, and this results in blood and protein loss. Chronic infection in the intestine results in iron deficiency anemia, accompanied by the loss of appetite, abdominal discomfort, and malnutrition due to protein deficiency. This can cause physical and cognitive impairment.

Evaluation

Clinical symptoms of Ancylostoma infection can be misleading because the symptoms are also present with other infections and nutritional-deficiency status. Routine blood findings can reveal iron-deficient anemia, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and sometimes, elevated IgE levels. Chest radiography may reveal diffuse alveolar infiltrates during the migration phase, but this is not helpful when the worms have already invaded the gut. These tests should be interpreted carefully since other helminth infections such as strongyloidiasis and ascariasis show the same blood and radiologic profile.

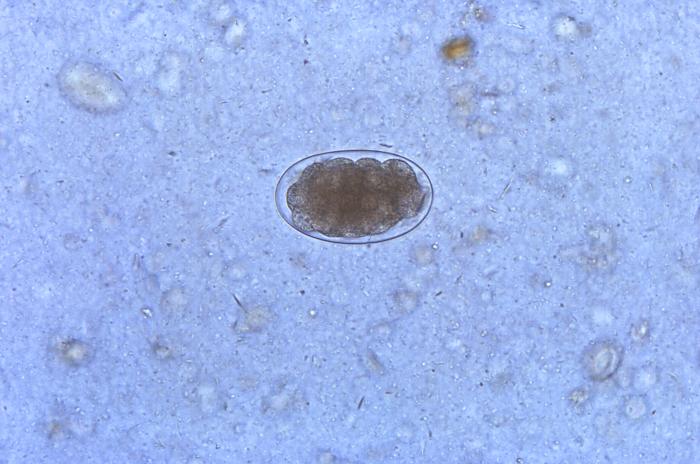

Conventional stool examinations, such as the Kato-Katz and formalin-ether concentration technique, are the gold standard for diagnosing Ancylostoma infection by detecting the presence of the eggs and adult worms. The morbidity of Ancylostoma infection can be determined by measuring the number of eggs per gram (EPG) in the stool. However, in some cases when the number of eggs is very low or after mass drug administration (MDA), stool examination is not helpful. Therefore, several laboratories have developing molecular-based examinations targeting the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) and 5.8S of the worms in the last few years. These molecular assays are still being validated to replace conventional methods.

In the case of CLM, stool examination is not very helpful, and diagnosis can be made clinically based on skin presentation since the larvae will be confined to the skin. If eosinophilic enteritis is suspected, the eggs will not be found in the stool because humans are not definitive hosts of A. caninum. Colonoscopy and laparotomies to obtain eosinophilic tissues for histopathology features to assess eosinophilic enteritis can be performed, but they are not recommended for routine testing. Serologic tests for A. caninum are not widely available, but several research laboratories have developed serologic testing for this species.

Treatment / Management

A single dose of albendazole or mebendazole or a 3-day dose of albendazole, mebendazole, or pyrantel pamoate is the recommended treatment for Ancylostoma infection. Ivermectin and pyrantel pamoate are the recommended treatment for A. ceylanicum infection, although benzimidazole drugs are effective as well. For pregnant women, deworming treatments are recommended during the second or third trimester of pregnancy after considering the risks and benefits of treatment. Iron replacement and nutritional support should be included in Ancylostoma management of infection to reduce the morbidity rates. After 2 to 3 weeks of treatment, stool examination and blood workup should be performed to evaluate treatment efficacy and to exclude the presence of any reinfection.[8][9][10]

Although CLM is a self-limited disease, complications such as secondary bacterial infection may occur if the CLM is untreated. A single dose of ivermectin or a 3-day course of albendazole can be used to stop the movement of the larvae. The topical application of 10% to 15% thiabendazole is also proven effective for CLM. Domesticated animals should be treated as well with anthelminthic drugs such as pyrantel pamoate, dichlorvos, febantel, fenbendazole, and mebendazole to stop the transmission cycle of the zoonotic Ancylostoma species.

Differential Diagnosis

All diseases that can cause chronic blood loss and iron-deficient anemia, for example, intestinal malignancy, intestinal polyps, hemolytic anemia, and other STH infection, should be ruled out to establish infection by Ancylostoma diagnosis. Contact dermatitis, migratory myiasis, scabies infection, and cercarial dermatitis have a common clinical presentation with CLM. Thus, they are hard to distinguish.

Prognosis

The prognosis for Ancylostoma infections is very good with proper treatment. Mortality is low, but morbidity can be significant, especially when reinfection occurs. Appropriate anthelmintic medication, iron supplementation, and proper diet will typically result in complete recovery, though some intellectual disability may remain.

Complications

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Intellectual disability

- Malabsorption

- Stunted growth

- Acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage

- Congestive heart failure

Deterrence and Patient Education

Mass drug administration of benzimidazole drugs such as albendazole and mebendazole are used as control strategies using preventive chemotherapy in endemic areas. However, other than preventive chemotherapy, improving general sanitation and hygiene can have a great impact on preventing infection and reinfection by Ancylostoma. Other easy preventive measurements include avoiding walking barefoot on beaches or endemic areas, cleaning up and preventing animal waste in public areas, and improving sanitary disposal of human waste.

Pearls and Other Issues

After many years of using anthelmintic MDA to treat and control Ancylostoma and other STH infections, the transmission of these worms is still ongoing. Hence, drug resistance exists. The increasing rates of drug failure and the inability to provide long-term protection raise concern for new ways to manage Ancylostoma and other STH infections, especially in endemic areas. Vaccines that could provide long-term protection and the ability to stop disease transmission have been developed and target several antigens of Ancylostoma species. The availability of the vaccine will be a huge benefit for public health in combating these infections.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of Ancylostoma infection is best accomplished with an interprofessional team consisting of an infectious disease expert, emergency and primary care clinicians, and pharmacists. The diagnosis can be difficult because the infection is not common in the US. The clinicians should be aware that the majority of people who are infected with Ancylostoma are from the endemic areas, or they are travelers who visit the endemic areas. Healthcare practitioners should take a careful history, including asking whether patients walk barefoot in endemic areas, have contact with domesticated animals, and inquire about the nutritional status and growth of pediatric patients to determine the presence of Ancylostoma infection. Once the diagnosis is made, the treatment with drugs like albendazole and mebendazole is highly effective. Public health clinicians and nurses play an important role in endemic areas by maintaining MDA programs and educating patients on the importance of improved sanitation and hygiene.