Continuing Education Activity

Corneal foreign bodies account for the second most common form of ocular trauma, with corneal abrasions being number one. In general, major morbidity such as visual acuity loss is not common. Many corneal foreign bodies are superficial and benign, albeit uncomfortable. This activity reviews the presentation of a patient with a corneal foreign body, its diagnosis, and management by an interprofessional team.

Objectives:

- Describe the presentation of a patient with a corneal foreign body.

- Review the evaluation of a patient with a corneal foreign body.

- Summarize the treatment options for corneal foreign bodies.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by a corneal foreign body.

Introduction

Corneal foreign bodies account for the second most common form of ocular trauma, with corneal abrasions being number one. In general, major morbidity such as visual acuity loss is not common. Many corneal foreign bodies are superficial, and benign, albeit uncomfortable.

Etiology

The etiology of corneal foreign bodies varies. Most commonly, it is a combination of a lack of protective eye-wear and high-risk activities. This includes grinding, hammering, drilling, and welding. In addition to these common causes, unexpecting causes are also seen, such as debris from driving or walking.

Epidemiology

The incidence of a corneal foreign body varies based on the text, but a Swedish study revealed the incidence of eye injuries was 8.1 per 1000, with 40% composed of corneal or conjunctival foreign bodies. The majority of these occur at work while performing high-risk activities, as mentioned previously. Noncompliance with well-fitting eye protection was common. In fact, during the 1991 Gulf War, data from one army field hospital showed 14% of the injuries seen were due to ocular trauma. Of these, 17% were corneal foreign bodies, and only 3% of the injured patients were wearing their provided protective goggles.[1]

Pathophysiology

The cornea is the anterior surface of the eye. It has attachments circumferentially to the sclera, at the level of the limbus. There are five total layers, with the top layer undergoing disruption in the setting of corneal abrasions, but a foreign body can lodge in any of the five layers. Foreign bodies can continue forward, creating an open globe injury, but outside the scope of this chapter.

Histopathology

Histopathology of the cornea will reveal five epithelial type layers. The first and outmost is called the epithelium. Classically this is 5 to 6 cell layers thick, consisting of epithelial cells. Below lies a single layer of basal epithelial cells referred to as Bowman’s layer. The stroma is the thickest layer, the thickest layer, comprises keratocytes. Beneath this lies Descemet membrane, and finally, a monolayer of corneal endothelium cells derived from neural crest cells. The five-layered cornea contains no vasculature and derives its nutrients from the aqueous humor of the anterior chamber itself. On microscopic exam, disruption with a foreign body can occur at any level.[2]

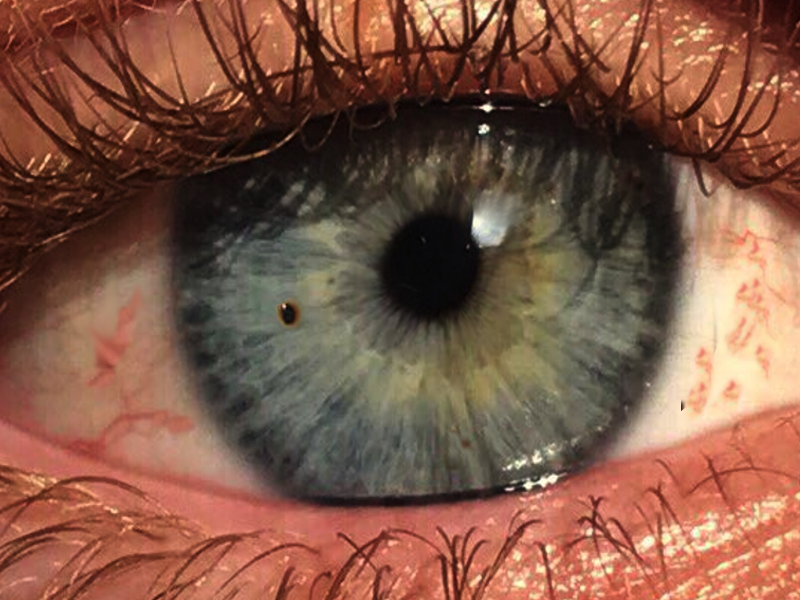

History and Physical

The history of present illness will typically be consistent with a sudden onset event. Persistent discomfort without relief causes people to seek care. History of visual acuity deficits is uncommon, although this may be perceived as such since the patient will have copious tearing and difficulty keeping their eye open. Accompanying symptoms are consistent with a generalized ocular inflammatory response, which will consist of tearing, redness, foreign body sensation, inability to find comfort with the eye opened or closed, and photophobia and blurred vision without overt visual acuity deficit. Most patients will report a high-risk activity such as hammering or grinding, and some will tell you the location of the foreign body.

Caution regarding permitting patients to guide your inspection is in order since although most patients will localize their pain from corneal foreign bodies, this has been shown to be inaccurate.

If present for greater than 24 hours, WBCs may migrate into the cornea/ anterior chamber as a sign of iritis. Gross hyphema, however, may indicate globe perforation. Other gross exam findings may show eyelid edema, as well as generalized or focal injection of the conjunctiva.

Evaluation

All suspected corneal foreign bodies, or ocular trauma in general, should be evaluated in a systematic, thorough, and meticulous. It is recommended to develop a standard routine eye examination to avoid the common mistake of focusing on the most obvious finding and missing something more subtle.

First, all ocular trauma patients should be administered adequate pain control to assist in obtaining an accurate and thorough exam.

Following pain control, the exam should start with what is often referred to as the three vital signs of the eye. This exam criterion is well documented as the visual acuity, pupillary exam, consisting of shape, reactivity, equality, accommodation, as well as any afferent pupillary defects seen. The third is the pressure of the anterior chamber. This should be obtained with care, although it may be skipped in some cases where globe perforation or rupture is highly suspected.

All patients suspected of having a corneal foreign body should also undergo a slit lamp examination. Care should be taken to inspect the entire eye as well as flipping the upper lid, as foreign bodies can hide under the tarsal plate and introduce micro-trauma with every blink of the eye. This should first be without fluorescein dye, inspecting the lids and lashes, the conjunctiva, the sclera, looking for injection, chemosis, anterior chamber depth, cell and flare within the anterior chamber, and as well as any readily apparent foreign bodies.

Upon adding the fluorescein, a general inspection should be performed again, looking for any corneal abrasions or lacerations. The dye will also allow you to perform the Seidel test, which, when positive, indicates globe perforation. In a positive test, you would expect to see a flow of aqueous humor as a waterfall appearance at the site of trauma. Another more subtle finding which indicates a positive Seidel test is a lighter color dye in one location due to the dilution of the dye by the aqueous humor. This is a finding in very small globe perforations.

Once the slit lamp examination is completed, there are other exams and diagnostics that you may choose to obtain as an adjunct. This may include a full dilated funduscopic exam or CT imaging to assess for intraocular or even intracranial foreign body. Limited bedside ultrasound is also useful to assess for vitreous hemorrhage or retinal detachment. However, extreme caution is recommended again, as any pressure to the globe may cause extrusion of inner contents through a possible globe perforation.

Treatment / Management

With any possible penetrating ocular injury, such as corneal abrasion, foreign body, or globe perforation, the mainstay of initial treatment is pain control, removal of contact lenses, and protection of the eye to prevent further trauma. Ocular patches are not recommended in the initial management, however protective eye shields may be helpful in children, or altered patients, to prevent further trauma from digitization.

Pain management can is obtainable with topical, oral, intramuscular, or intravenous medications. The most efficacious is topical tetracaine. However, overuse can lead to long-term cornea breakdown, and its use is reserved for the initial hour or two.

Cycloplegic eye drops may be helpful, as well as placing a patch over the unaffected eye, to minimize as much pupillary movement as possible. Topical ketorolac has also recently been shown to be of benefit. However, this is avoided in the pregnant population.

Finally, systemic pain relief may be necessary if the patient cannot tolerate your examination. However, caution should be used with this approach, as dependence and misuse syndrome has become more prevalent in recent years.

Foreign body removal should commence as soon as possible; within 24 hours is ideal, as, after this time, the foreign body can become embedded within the stroma of the cornea, and this makes removal more difficult. If the foreign body is thought to be or has physical exam findings consistent with full stromal thickness, the object should be removed on an emergent basis by an ophthalmologist.

There are many ways to remove a foreign body, but there is a consensus that a step-wise approach is most reasonable. The following techniques are the recommendations after thorough examination rules out globe perforation.

Simple irrigation and a moist cotton swab is the first step. The majority of recent and superficial foreign bodies can be successfully removed this way. If this is unsuccessful, the bevel of a needle is usable under slit lamp guidance. The physician may use their personal preference, but most texts recommend a 25 to 30 gauge needle connected to a TB syringe for the utmost control.[3]

Another method to remove it is with an ophthalmic corneal burr also referred to as a spud, or more commonly the “Alger brush.” This has a couple of distinct functions. As it rotates, it can be used to essentially flick out the foreign body, although more commonly, it is used to shave down the rust ring from a metallic foreign body.

When a foreign body is full-thickness or intra-ocular, there are limited options. If the object is thought to be inert, such as glass or plastic, the patient can be observed serially. All metallic foreign bodies should be removed regardless of the depth, as they react with the stroma, causing a rust ring. Small rust rings can be left, as they will often go away on their own, or they can be serially shaved away as the stroma continues to regenerate. Central corneal foreign bodies or rust rings should undergo aggressive removal, as they have the most impact on future vision. Secondary iritis can be a finding with inadequate removal of rust rings.

Upon successful removal of the corneal foreign body, treatment consists of pain control, follow-up, and consideration given to prophylactic antibiotics. When choosing an antibiotic, contact lens wearers should have anti-pseudomonas coverage. In one study, 90% of the bacteria cultured from corneal foreign bodies were sensitive to fluoroquinolone drops.[4] Pain relief with topical ketorolac has not been shown to impair corneal healing. Cycloplegics can also be used for comfort, although atropine should be avoided, as this can last up to 2 weeks. Lubricating eye drops are also helpful. There has been considerable controversy over employing an eye patch. It is contraindicated in contact lens wearers, as well as organic foreign bodies, as it can increase the rate of infection. However, patches have not shown to be of benefit in time to corneal healing or reduction in symptomatic days. After removal of a foreign body, treatment is the same as an abrasion, and a prospective, three-arm, randomized study showed patching showed no difference in days to comfort or healing.[5]

Differential Diagnosis

With any painful red eye, with a foreign body sensation, other etiologies must be ruled out. A broad differential diagnosis is helpful. The following differential for corneal foreign bodies includes but is not limited to:

- Corneal abrasion or laceration

- Globe perforation or rupture

- Intraocular foreign body

- Retinal or vitreous; detachment or hemorrhage

- Uveitis

- Iritis,

- Endophthalmitis

- Ultraviolet keratitis

- Exposure

- Chemical injuries

Infectious causes include corneal ulcers, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, herpes simplex keratoconjunctivitis, or other simple viral or bacterial conjunctivitis.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Most complications, toxicities, and side effects occur with metallic foreign bodies. Full-thickness foreign bodies leading to globe perforation comes with its particular complications; however, that is outside the scope of this topic.

Metallic foreign bodies cause a previously described rust ring. This can progress to reactive iritis, causing significant pain and vision loss and put the patient at risk for secondary infection or keratitis.

These complications and side effects can be managed effectively by prompt foreign body removal, rust ring removal, and close outpatient follow-up with an ophthalmologist.

Prognosis

The prognosis for corneal foreign bodies varies with location and depth, and type of substance. Superficial and peripheral corneal foreign bodies have an excellent prognosis, without long-term vision deficits, in most cases.

Centrally located or full-thickness corneal foreign bodies still have an excellent long-term prognosis. However, they are associated with more complications and require closer and more frequent follow-up appointments.

All centrally located rust rings come with a greater risk of visually significant scarring. However, close and frequent follow up can help avoid this outcome.

Complications

Complications are uncommon, although they are serious. These consist mostly of reactive iritis due to corneal foreign bodies not removed within 24 hours or also seen with retained rust rings. There is also the risk of visually significant scarring with centrally located foreign bodies, especially with retained rust rings.

Consultations

All patients with a corneal foreign body require close follow-up with an ophthalmologist.

Patients with peripherally located corneal foreign bodies, without retained foreign material, can follow up as an outpatient in 2-3 days.

Centrally located corneal foreign bodies or retained rust rings should be seen immediately (ideally), although within 24 hours of the event is reasonable.

Retained inert foreign bodies should be followed up with regularly, with exact timing determined on a case by case basis, which is also the case with an intraocular foreign body.

Once the patient is back to their baseline, a yearly ophthalmologic follow-up is recommended unless otherwise specified.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Most corneal foreign bodies directly result from non-compliance with well-fitting safety goggles. Patients should receive education on wearing these while performing high-risk activities and the appropriate fit, as loose-fitting or inadequate protective eyewear can also result in ocular trauma.

Pearls and Other Issues

It is important to recall that when examining a patient with ocular trauma, finding one site of traumatic injury does not rule out additional corneal foreign bodies elsewhere.

Always complete your examination in a standard, routine, thorough, and meticulous manner.

Always remember to flip the upper eyelid and remove contact lenses before the examination.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Any patient with a corneal foreign body comes into contact with multiple health care providers. A significant number of patients are seen by primary care providers, including physicians, nurse practitioners, and optometrists. Many of these patients arrive at the emergency department. Here, nurses will perform triage, and they may already notice an irregular pupil and opted to cover the eye to protect it like an open globe. They may also take out an intraocular pressure meter, which will guide the exam. As one retrospective chart review study showed, intraocular pressure was one determining factor in open globe outcomes.[6] [Level 4]Patients may also seek the counsel of pharmacists, who will instruct them on the proper use of eye drops. Interprofessional teamwork is essential. Once the initial stages of this condition are under control, close follow-up with a specialist is needed. Many healthcare providers play an essential role.