Introduction

The pericardium is a fibrous sac that encloses the heart and great vessels. It keeps the heart in a stable location in the mediastinum, facilitates its movements, and separates it from the lungs and other mediastinal structures. It also supports physiological cardiac function.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

The pericardium consists of two layers: the fibrous and the serous. The fibrous pericardium is a conical-shaped sac. Its apex is fused with the roots of the great vessels at the base of the heart. Its broad base overlies the central fibrous area of the diaphragm with which it is fused. Weak sterno-pericardial ligaments connect the anterior aspect of the fibrous pericardium to the sternum. The serous pericardium is a layer of serosa that lines the fibrous pericardium (parietal layer), which is reflected around the roots of the great vessels to cover the entire surface of the heart (visceral layer). Between the parietal and visceral layers is a potential space that may be filled with a small amount of fluid. The part of the visceral layer that covers the heart, but not the great vessels is called the epicardium.

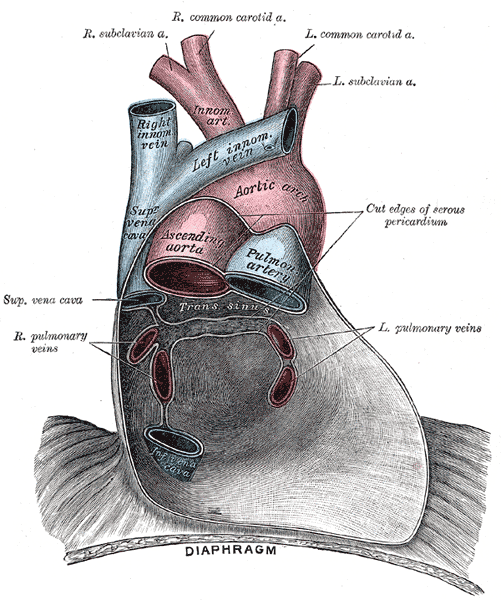

As the serous pericardium reflects off various cardiac structures, it forms two sinuses: the transverse sinus and the oblique sinus. The oblique sinus is a cul-de-sac extending superiorly from the inferior vena cava between the two left pulmonary veins on one side and the two right pulmonary veins on the other. Its anterior wall is formed by the posterior wall of the left atrium, between the four pulmonary veins. The oblique sinus provides expansion space for the left atrium. The transverse sinus is open at both ends and formed by the reflection of visceral serosal pericardium from the posterior aspects of the aortic and pulmonary trunks over to the anterior aspect of the atrium. Thus, a finger in the transverse sinus will pass behind the aortic and pulmonary trunks, in front of the superior vena cava on the right, and the left atrial appendage on the left.

The pericardial sac positions the heart in the mediastinum and limits its motion while providing a lubricated slippery surface for the heart to beat inside and the lungs to move outside. The pericardium prevents the excessive dilatation of the heart, and in pathological states, it can limit the overfilling of the heart, which would result in low cardiac output. It also influences the pressure-volume relationships of cardiac chambers by providing limited space for the heart as a whole. The pericardium also equalizes hydrostatic, inertial, and gravitational forces maintain the geometry of the left ventricle, and acts as a mechanical barrier to infection.

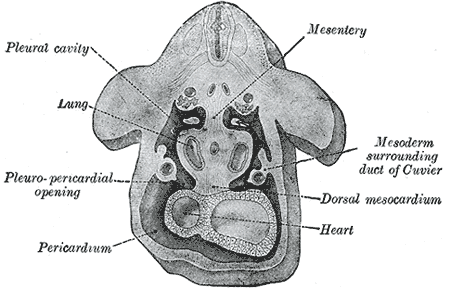

Embryology

The fibrous pericardium is derived from the septum transversum in the embryo. The septum transversum is a thick mass of cranial mesenchyme that is formed on day 22. During craniocaudal folding, it assumes a position caudal to the developing heart. Both the diaphragm and the pericardium, among other structures, develop from the septum transversum.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

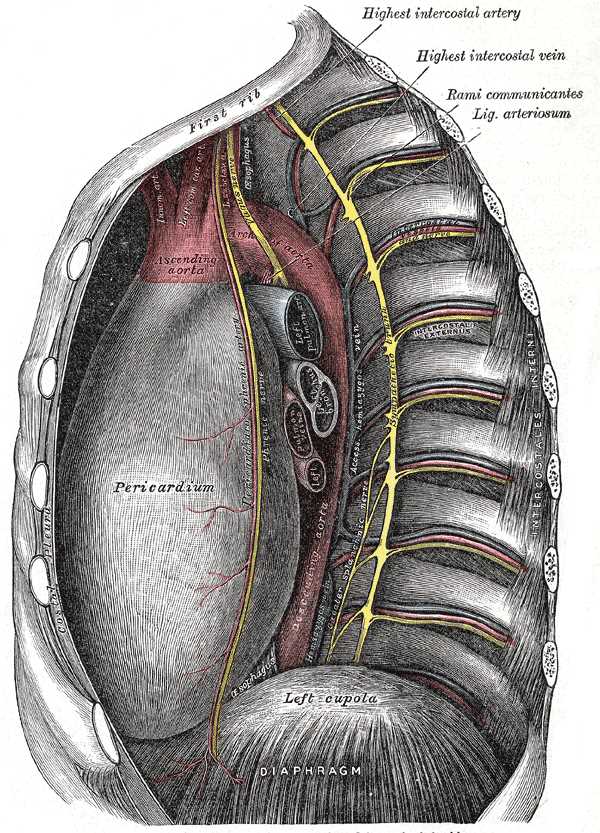

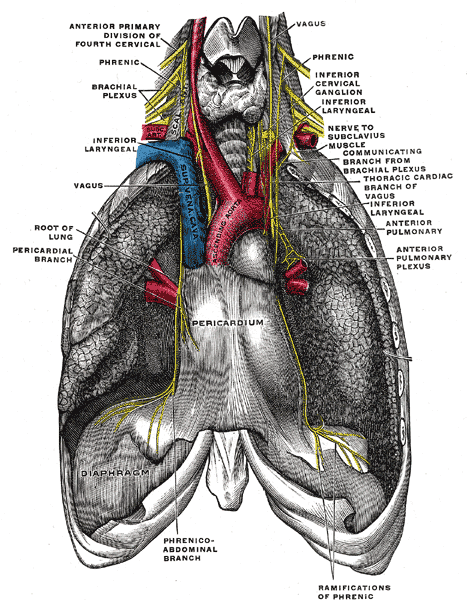

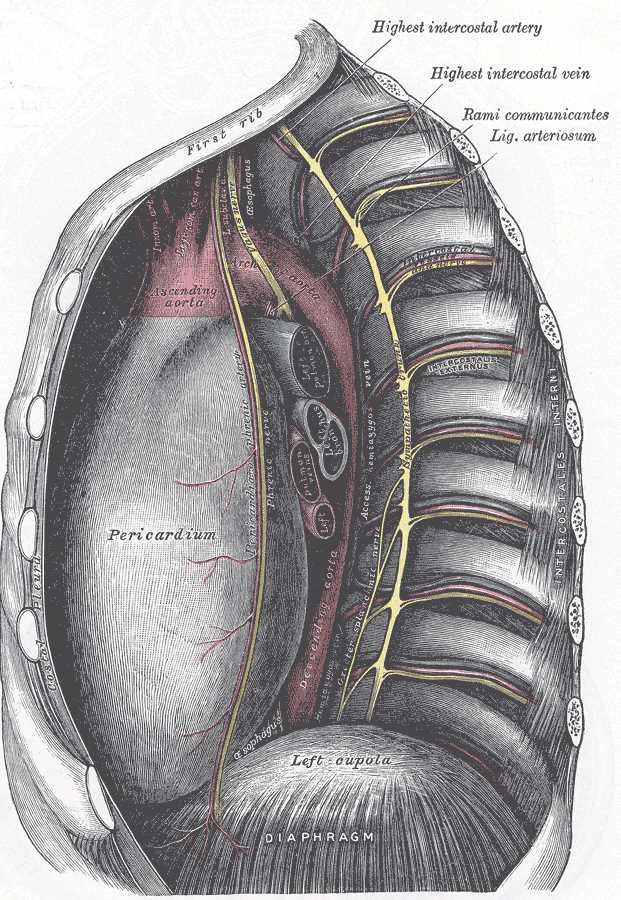

The pericardium is supplied by the pericardio-phrenic branches of the internal thoracic arteries. The visceral pericardium drains lymph into the tracheal and bronchial lymph chain. The parietal pericardium has lymphatic drainage similar to that of the sternum and diaphragm. [2] The lymphatics from the ventral surface of the parietal pericardium pass along the phrenic nerves cranially. On the lateral and posterior surfaces, the lymphatics anastomose with lymphatics of the reflected mediastinal pleura. [4]

Nerves

The fibrous pericardium and the parietal part of the serosal pericardium are supplied by the phrenic nerve. The visceral pericardium is insensitive; therefore, the pain from the pericardium originates in the parietal layer only and is transmitted by the phrenic nerve.

Physiologic Variants

Rarely the pericardium may be congenitally absent. This usually involves a portion or the whole of the left parietal pericardium. Pericardial cysts are rare remnants of defective embryologic development and are benign; their importance lies in differentiation from a neoplasm. [5]

Surgical Considerations

During cardiac surgery, an incision is made through the pericardium to access the heart. Such handling of the pericardium can result in inflammation and thickening of the pericardium. This may cause the pericardium to become attached to the back of the sternum around the incision site, making repeat surgery very complicated.

A needle passed just below and to the left of the xiphoid process and pointed towards the left shoulder will pass above the diaphragm to enter the pericardial space next to the right ventricle. This approach is used to drain pericardial effusions but also can be used as access for performing catheter-based procedures over the epicardial surface of the heart, such as catheter ablation for arrhythmias.[6][7][8]

Clinical Significance

Pericarditis

Inflammation of the pericardium is called pericarditis. Its origin can be infectious, immunologic, metabolic, neoplastic, traumatic, or idiopathic. A myocardial infarction can also cause localized pericarditis of the area overlying the infarct. Postinfectious fibrinous pericarditis occurs within 1-3 days of myocardial infarction, whereas Dressler syndrome occurs weeks to months after myocardial infarction. Acute pericarditis often produces fever, “pleuritic” pain in the center of the chest that radiates to the back and varies with deep breathing, and a pericardial friction rub on auscultation. The pain increases upon lying flat and is relieved by sitting upright. An electrocardiogram will show diffuse ST elevation and PR depression. The condition is usually short-lived and is treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and colchicine. NSAIDs inhibit the activity of cyclooxygenase enzymes, whereas colchicine blocks mitotic cells in metaphase. [9]

Pericardial Effusion

Normally the pericardium contains only a few milliliters of fluid that act as a lubricant, but pericarditis and other conditions may lead to the pericardium filling with hundreds of milliliters of exudative or transudative fluid. This is called pericardial effusion and can be easily recognized on an echocardiogram. A chest x-ray may also show an enlarged and bag-like cardiac shadow when a significant pericardial effusion is present.[10]

Cardiac Tamponade

Pericardial effusion or bleeding into the pericardium due to injury can limit the space available for the expansion of the heart. If this is severe enough to limit venous return, cardiac output falls drastically as a result of the heart not being able to fill with blood. This condition is called cardiac tamponade. Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition and often requires urgent attention. It is recognized clinically by the triad of hypotension, muffled heart sounds, and jugular venous distension. Patients can also have a phenomenon known as pulsus paradoxus, which is a decrease in systolic blood pressure by more than 10 mm Hg during inspiration. Echocardiography is the first-line imaging modality used. Treatment consists of draining the pericardial fluid using a needle, placement of a catheter in the pericardium for continuous drainage, or surgical creation of a 'window' between the pericardial and pleural spaces.

Constrictive Pericarditis

Constrictive pericarditis occurs when long-term inflammation of the pericardium causes thickening, scarring, and often calcified pericardium, which limits the diastolic filling of the ventricles. This can be a complication of acute pericarditis, especially when the cause of pericarditis is neoplastic, bacterial, or radiational. It is also common in patients with tuberculosis and following cardiac surgery. Patients typically present with symptoms of fluid overload, including jugular venous distension, hepatomegaly, and peripheral edema. Additional findings include Kussmaul's sign, which is a paradoxical increase in jugular venous pressure during inspiration, and a pericardial knock, which is is an extra-systolic heart sound heard immediately after S1.