Continuing Education Activity

Platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome (POS) is a rare clinical condition characterized by dyspnea (shortness of breath) and hypoxemia (low blood oxygen levels) worsening in the upright position and improving in the supine position. The condition is usually a symptom of an underlying disease. Specialists in the interprofessional team have the crucial role of determining the right management approach for patients with this condition, which often presents a diagnostic dilemma for medical practitioners.

This activity reviews the causes of POS, explains the condition's pathophysiology, highlights the important parts of the evaluation process, discusses the general management approach, and describes the interprofessional team members' roles in caring for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Identify the key clinical features associated with platypnea in patients, recognizing its unique symptomatology.

Implement evidence-based diagnostic and therapeutic interventions to address the specific etiology of platypnea in individual patients.

Apply current guidelines and best practices in the management of platypnea, tailoring interventions to each patient's unique needs.

Collaborate with interprofessional healthcare teams to optimize care for patients with platypnea, fostering a comprehensive and coordinated approach.

Introduction

Platypnea is a descriptive term for breathing difficulty in the upright position that improves in the supine position. Orthodeoxia has a similar meaning but emphasizes the association of breathlessness with the upright position. The diagnosis of platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome (POS) is made when shifting from the supine to the upright position is accompanied by a reduction of oxygen saturation (SaO2) greater than 5% and of arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) greater than 4 mm Hg.

POS is commonly associated with intracardiac shunting, as in cases of patent foramen ovale (PFO), atrial septal defect (ASD), atrial septal aneurysm (ASA), and congenital cardiomyopathy. Extracardiac shunting, as in pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (PAVM), hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS), and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), is also a possible cause. Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) mismatches, seen in conditions like pneumonectomy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), interstitial lung disease (ILD), and cryptogenic organizing fibrosis, can contribute to the symptoms. PFO is the most common structural anomaly associated with POS, often remaining asymptomatic for many years.[1]

Platypnea-orthodeoxia is a clinical syndrome first observed in 1949 and originally called "orthostatic cyanosis." The terms "platypnea" and "orthodeoxia" were later introduced in 1969 and 1976, respectively, to characterize the condition in which breathlessness and SaO2 reduction worsen when upright and improve when lying down.[2]

Etiology

The literature has broadly classified the etiology of POS into intracardiac and extracardiac shunts. Intracardiac shunting-related conditions most commonly associated with POS include PFO, ASD, and ASA.[3] Extracardiac pathologies are further divided into intrapulmonary and extrapulmonary shunts. Examples of intrapulmonary causes are PAVM and lung parenchymal disease. HPS produces extrapulmonary shunting that gives rise to POS. Other articles implicate fat embolism and Parkinson disease as possible causes of POS, though the precise mechanism giving rise to POS in these disorders remains controversial.[4]

Epidemiology

No data currently exists estimating the incidence of POS. Most cases go undetected unless clinicians specifically ask about the symptoms. Additionally, the degree of positional dyspnea or SaO2 reduction is not routinely determined during physical examination. Therefore, positional oxygenation level alterations can be easily overlooked.[5][6]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of POS is not entirely understood, but the condition is highly associated with positional intracardiac or intrapulmonary right-to-left shunting. The shunts may arise from congenital cardiac disorders like PFO and acquired ones like pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism, pneumonectomy, and significant pericardial effusions.

POS may also result from worsening V/Q mismatch in patients with underlying lung disease, especially when the lung bases are most affected. This mechanism has been reported in cases of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in the lung bases and severe basilar pneumonia. The same can develop in HPS, as the upright position causes more blood to flow to the lung bases.[7]

The shunt fraction of total cardiac output (Qs/Qt) can be calculated by supplying the patient with 100% oxygen for 20 to 30 minutes and then using this equation:[8]

Qs/Qt (Shunt Fraction): (CcO2 - CaO2) / (CcO2 - CvO2)

In this equation, CcO2 is the end capillary O2 content, CaO2 is the arterial blood's oxygen content, and CvO2 is the mixed venous blood's oxygen content. In healthy individuals, the physiologic shunt fraction is about 5%.

History and Physical

POS is a symptom and not a disease. History and physical examination should focus on determining the condition's underlying cause.[9] On history, patients may describe dyspnea precipitated by assuming an upright position that improves when reclining. A history of a longstanding primary or secondary cardiopulmonary condition and poor exercise tolerance may be elicited. The patient may likewise report associated symptoms like chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, and fainting spells.

Physical examination is notable for hypoxemia in the upright position, improving in the reclining position. Other findings depend on POS' underlying cause. Cardiac auscultation may reveal murmurs in patients with congenital heart anomalies, though individuals with PFO may have normal heart sounds. Positional hypoxemia in the presence of a right-to-left shunt may not respond to oxygen supplementation.[16] Abnormal breath sounds, cyanosis, and clubbing may be present in patients with either heart or lung pathology. Signs of chronic hepatic disease, such as spider nevi, palmar erythema, ascites, and anasarca, may be present in patients with HPS.

Evaluation

Laboratory tests should focus on determining POS' underlying etiology. Patients with PFO may have a normal electrocardiogram, chest x-rays, blood counts, and metabolic panels. However, echocardiography will reveal the pathology.

Agitated saline bubble echocardiography distinguishes intracardiac from extracardiac shunts, making it an excellent initial imaging tool for POS evaluation. The appearance of microbubbles in the left atrium during the first 3 beats after opacification of the right chambers suggests an intracardiac shunt. Meanwhile, microbubble appearance after 3 to 6 beats is more consistent with extracardiac shunting. The Valsalva maneuver may help intensify right-to-left shunting. Other tests that can help evaluate shunts include contrast-enhanced echocardiography, macroaggregated-albumin scintigraphy, and invasive angiography.[10]

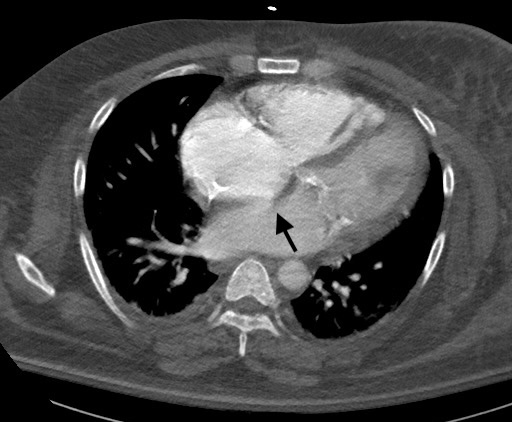

Plain chest radiography is usually not sensitive but may show an underlying lung disease that can explain POS occurrence. PFO may be detectable on computed tomography (CT) without contrast (see Image. Patent Foramen Ovale Computed Tomography). CT with contrast is useful when looking for an arteriovenous malformation (AVM).[11]

Patients with hepatic disease will have abnormal liver enzyme levels and coagulation test results. HPS arises from the triad of liver disease, arterial deoxygenation from pulmonary gas-exchange abnormalities, and evidence of intrapulmonary vascular dilatations. The following are the diagnostic criteria for this condition:[12]

- The presence of liver disease, portal hypertension, or both

- An elevated room air alveolar-arterial oxygen gradient {P(A-a)O2 gradient} >15 mm Hg or >20 mm Hg in individuals older than 65

- Evidence of intrapulmonary vascular dilatations in the basal parts of the lungs

- Absence of other significant cardiopulmonary disease

Referral to specialists, such as pulmonologists, cardiologists, hepatologists, or interventional radiologists, is essential to determine the need for other specific tests.

Treatment / Management

POS interventions should be directed toward addressing the underlying disorder. Detailed management of each disease is beyond the scope of this review, but persistent hypoxia warrants oxygen supplementation. Early referral to specialists like cardiologists or pulmonologists can help refine the evaluation and management strategies.

Patients with a possible cardiac condition may be referred to a cardiologist. PFO usually does not require any treatment as it may be present in up to 25% of people. However, POS and concerns for a paradoxical embolic stroke warrant a referral to a cardiovascular surgeon for possible surgical closure.

Underlying lung diseases must be treated appropriately and in a timely fashion. Patients with pneumonia may be given antibiotics. A pulmonology referral is required to treat complex pulmonary conditions like ILD. Interventional radiologists may perform embolotherapy for large PAVMs.[13]

Liver transplantation, performed by a liver transplant specialist, is warranted in cirrhosis with HPS. Supportive treatment may be given to patients while waiting for surgery.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

Positional dyspnea is a symptom of many disorders. The differential diagnosis of POS includes an extensive list but may be classified into the following:

- Intracardiac shunting: PFO, ASD, ASA, valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathy

- Pulmonary vascular disorders: PAVMs, pulmonary hypertension

- Respiratory conditions: COPD, pneumonia, ILD

- Extrapulmonary conditions: diaphragmatic hernia or paralysis, liver failure

- Miscellaneous: orthostatic hypotension from causes like severe dehydration and blood loss, sleep-related breathing disorders

POS is a rare condition requiring a multidisciplinary approach for complete evaluation and appropriate management.

Prognosis

The prognosis of POS mainly depends on the severity of the underlying condition and the appropriateness of management.[15] Outcomes are generally excellent if the underlying cause is treated promptly and the patient completes rehabilitation. Poor prognostic factors include delayed management, poor treatment response, suboptimal cardiac function, and the presence of systemic complications.

Complications

POS' underlying conditions cause complications, not POS itself. These complications include the following:

- Persistent hypoxemia, leading to chronic heart failure and multiple organ dysfunction

- Risk of thromboembolic events, which usually accompanies intracardiac shunts

- Reduced quality of life, which may be due to shortness of breath and related symptoms like fatigue and cognitive impairment

- Surgical complications, including anesthesia-induced reactions, bleeding, and infection, in conditions treated surgically

- Progression of the underlying conditions, which may ultimately lead to death, as in cases of liver and heart failure

Accurate diagnosis and timely treatment are crucial in preventing or mitigating POS' potential complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Managing the underlying conditions causing POS should be the main focus of POS-preventive strategies. Healthcare providers must emphasize several aspects when counseling patients. First is awareness of the possible causes of the condition. Health literacy helps improve health-seeking behaviors. Second is the importance of regular medical checkups. Routine health examinations can detect conditions that can give rise to POS early. Timely treatment of such illnesses can prevent this complication.

Third is the importance of maintaining a healthy lifestyle. POS may arise from preventable diseases like pneumonia, liver failure, and COPD. Personal hygiene, sanitation, a balanced diet, exercise, and smoking abstinence can help prevent these illnesses and, consequently, POS. Fourth is controlling chronic conditions and POS triggers. Adherence to long-term treatment plans helps delay the onset of complications in people with conditions putting them at risk of POS.

Fifth is genetic counseling for patients with POS that may arise from a hereditary condition. Parents concerned about passing on POS-related genetic disorders may be offered guidance for family-planning decisions and prenatal testing. Sixth is seeking medical attention promptly for new or worsening symptoms. Prompt management of conditions that can produce POS usually results in better outcomes.

The occurrence of POS may be hard to predict for most people. However, awareness of the condition's possible origins and preventive strategies can help patients avoid its development.

Pearls and Other Issues

The most important points to remember about POS diagnosis and management are the following:

- POS is a rare condition usually resulting from significant intracardiac or extracardiac right-to-left shunting.

- Measuring oxygen saturation in different positions should be performed any time POS is reported.

- Treatment of POS focuses on managing the underlying cause.

- Early referral to specialists is essential in optimizing diagnostic tools and management strategies.

- Preventive measures include actions that help prevent or treat the underlying causes of POS.

Prompt detection and intervention improve outcomes in patients with POS.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis of platypnea is usually complex and requires a thorough clinical and radiological assessment of the patient. The clinical outcomes depend on identifying the underlying etiology. Care coordination and early involvement of an interprofessional team are essential for early diagnosis and targeted treatment.[9] The interprofessional team who will care for patients with POS include the following members:

- Primary care or emergency medicine physician: These providers are the most likely to encounter patients with POS for the first time. These physicians will order the proper monitoring of vital signs and diagnostic tests and provide the initial treatment.

- Nursing staff: These professionals will properly monitor changes in the patient's vital signs and confirm the presence of positional hypoxia in patients with POS. Nurses will also ensure patient comfort, administer medications, help educate patients, and coordinate care with other healthcare team members.

- Radiologist: This physician will evaluate imaging findings to diagnose the underlying cause of POS.

- Pulmonologist, cardiologist, internist, or hepatologist: The expertise of these specialists is valuable in determining the etiology of POS and the appropriate management approach.

- Respiratory therapist: This provider will help patients improve lung function.

- Thoracic and cardiovascular surgeon, interventional radiologist, or liver transplant specialist: These physicians will perform surgical procedures if necessary in managing POS.

- Rehabilitation team: Physical and occupational therapists will help patients recover function and return to normal activities.

Collaborative efforts among team members are essential for accurate diagnosis, appropriate management decisions, and improved patient outcomes.