Continuing Education Activity

Temporal arteritis (TA), also called giant cell arteritis (GCA) or cranial arteritis, is a systemic inflammatory vasculitis of medium and large-sized arteries occurring most frequently in adults. TA leads to ischemic optic neuropathy with potentially irreversible vision loss on the affected side with potential contralateral involvement. Left untreated, it can result in many systemic, neurologic, and ophthalmologic complications. Although the temporal artery is most commonly involved, other arteries may be affected. These include the aorta and the subclavian, iliac, ophthalmic, occipital, and vertebral arteries. Although they do not always coexist, TA is commonly associated with polymyalgia rheumatica. This activity will review the pathophysiology of temporal arteritis, the population most at risk, and the best treatment approach according to current evidence. This activity will highlight the role of the interprofessional team in recognizing and treating patients affected by this condition.

Objectives:

Describe the etiology of temporal arteritis.

Review the potential differential diagnoses of temporal arteritis.

Outline the treatment strategy for a patient with temporal arteritis.

Summarize the importance of collaboration and coordination amongst the interprofessional team in optimizing the outcomes for patients with temporal arteritis.

Introduction

Sir Jonathan Hutchinson first described giant cell arteritis (GCA) in 1890, and later, Dr. Bayard T. Horton described the histologic appearance of granulomatous arteries of temporal arteritis. [1][2] GCA has also been known by many other names, including Horton arteritis, temporal arteritis, arteritis of the aged, cranial arteritis, and granulomatous arteritis. GCA is a systemic inflammatory vasculitis of medium and large-sized arteries and is the most common form of vasculitis affecting adults in western countries. Over the past decade, there has been significant progress in understanding the pathophysiology and diagnosis, and management of GCA. Typically, GCA is a disease of the elderly and does not occur before the age of 50. It is frequently associated with polymyalgia rheumatica. The majority of symptoms of temporal arteritis result from the involvement of the cranial branches of the aorta although the involvement of other large vessels such as thoracic/abdominal aorta and its branches is not uncommon. The most feared complication of GCA is irreversible visual loss caused by ischemic optic neuropathy, which can be bilateral. Early treatment with corticosteroids can be vision-saving, and recent studies showing the efficacy of interleukin-6 inhibitors in GCA have shown a promising future in the management of GCA.

Etiology

Giant cell arteritis results from immune-mediated inflammatory changes in the vessel wall. The exact etiology is unknown, although several genetic and environmental factors have been hypothesized. Advancing age and Scandinavian ancestry are known risk factors.[3] An association with Toll-like receptor 4 gene polymorphism as well as HLA-DRB1*04 has been identified.[4][5] Of all systemic vasculitides, GCA is most closely associated with HLA Class II genes. Smoking has been associated with a higher risk of GCA, especially in women. Several infectious etiologies have been investigated, including parvovirus B19, Mycoplasma, VZV, parainfluenza virus, Herpes virus, Chlamydia, and only circumstantial evidence without any confirmatory proof of an infectious etiology exists.

Epidemiology

GCA is the most common vasculitis affecting adults in western countries, with an incidence of 20/100,000 in people older than 50 years of age. It does not occur in adults below 50 years of age, and the mean age of onset is 75 years. It is more common in females with a male to female ratio of about 1 to 2. The incidence is highest in Scandinavians, Americans of Scandinavian accent, and is lowest in African Americans, Northern Indians, and Japanese.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

The exact cause of giant cell arteritis is unknown. Inflammation of medium-large-sized arteries originating from the arch of the aorta is the hallmark of the disease. GCA is characterized by innate and adaptive immune system dysregulation, and the pathophysiology is thought to involve the body's inappropriate response to vascular endothelial injury. GCA is characterized by a predominant Th-1 immune-mediated response with significant expression of IFN-Gamma. A Th-17 immune response has been identified recently, which responds better to glucocorticoids.[8]

The initial insult to the endothelium (injury, trauma, infection, drug, autoantigen) results in activation of the dendritic cells residing in the adventitia. The activated dendritic cells release chemokines attracting CD4+ helper T cells and macrophages into the arterial wall. The activated dendritic cells also release IL-6 and IL-18, which activate the T-cells and promote IFN-gamma release from the T-cells. The IFN-gamma release from T-cells promotes inflammation, macrophage activation, and granuloma formation. The activated macrophages release matrix metalloproteinase and oxygen free radicals causing endothelial damage and disruption of the internal elastic lamina. They also secrete nitric oxide in the intima and unite to form syncytia, leading to "giant cell" formation. The macrophages also contribute to systemic inflammation by releasing IL-1 and IL-6.[9][10]

Histopathology

Histopathology is the gold standard for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Early in the disease, the histopathological changes are confined to the region of the internal or external elastic lamina or adventitia or sometimes only vasa vasorum. Later in the disease, transmural inflammation with intimal thickening and marked inflammation of the inner portion of media adjacent to the internal elastic lamina are evident. In addition to the inflammatory infiltrate, other histopathological features of GCA are luminal narrowing, intimal proliferation, and disruption of the internal elastic lamina. Thrombotic changes can be seen at active sites.

Fibrinoid necrosis is not a feature of GCA and usually indicates alternate diagnoses such as ANCA-associated vasculitis. Inflammation is often segmental, leading to skip lesions. Inflammatory infiltrate typically consists of CD4+ T-cells and macrophages. Histiocytes, plasma cells, and fibroblasts are frequently present, while neutrophils and eosinophils are very rarely seen. Multinucleated giant cells are present in only 50% of the cases of GCA and are not a requirement for the diagnosis of GCA.[11]

History and Physical

Constitutional Symptoms

Although non-specific, almost all patients with giant cell arteritis have one or more constitutional symptoms (weight loss, fever, fatigue, anorexia, malaise), which are the most common symptoms of GCA. Fever is usually low-grade and is present in up to 40% of GCA patients at presentation.[12] Further, GCA accounts for more than 15% of all fevers of unknown origin in patients 65 years of age and older.[13]

Headache

New-onset headaches or a change in baseline headaches in an elderly patient shall always raise a concern about the possibility of GCA. However, headaches may be absent in patients with isolated extra-cranial large vessel involvement, accounting for 10 to 15% of GCA. More than 75% of patients with GCA have headaches as a symptom, which is usually temporal but can be occipital, periorbital, or non-focal as well. Headaches have an insidious onset and gradually progress over time, although they may spontaneously resolve rarely, even in the absence of treatment (even while the disease process is ongoing). The intensity and quality of headaches vary, and headaches can be severe and not respond to typical over-the-counter analgesics. Scalp tenderness while combing or brushing hair is frequent and can be focal in the temporal areas or diffuse. In rare and severe cases, scalp necrosis can be seen.

Jaw Claudication

Jaw claudication or pain and discomfort while chewing or talking due to decreased blood supply to jaw muscles is a rather specific symptom for GCA and is seen in more than 30% of patients with GCA. Jaw claudication carries a high positive likelihood ratio for a positive temporal artery biopsy. Severe compromise in blood flow can lead to tongue necrosis which is rarely seen.

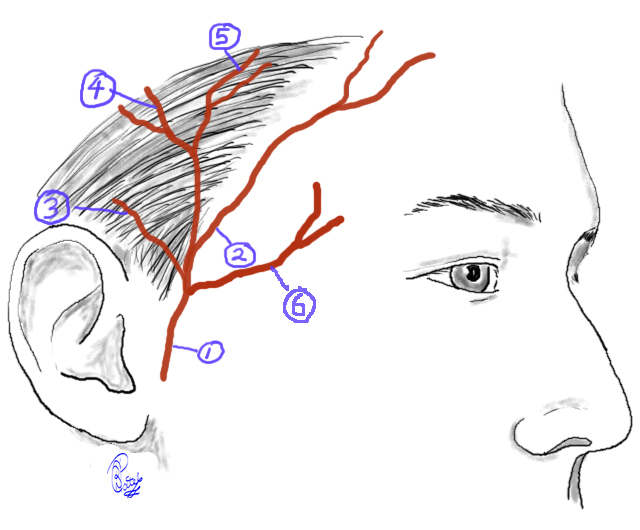

Temporal Artery Abnormality

Enlargement, nodular swelling, tenderness, loss of pulse of the temporal artery, either unilateral or bilateral, are seen in up to 50% of patients with GCA. Temporal artery nodularity also carries a high positive likelihood ratio for a positive temporal artery biopsy.

Visual Symptoms

Visual complications are seen in up to 15% of patients with GCA and, most commonly, are due to anterior ischemic optic neuropathy caused by vasculitis involving the ophthalmic artery or the posterior ciliary arteries (although can be due to ischemia anywhere in the optic pathway).[14] Patients may initially have transient vision loss or amaurosis fugax. Vision loss is usually sudden and painless. It can be initially unilateral or bilateral, and there is a high risk of bilateral vision loss if unilateral vision loss is not urgently treated with high-dose corticosteroids. Vision loss can be partial or complete and is irreversible.[13] Fundoscopy initially reveals pallor and edema of the disc and, eventually, optic atrophy. Diplopia can also be seen in GCA due to oculomotor nerve palsy due to ischemia and usually precedes vision loss.

Polymyalgia Rheumatica (PMR)

Both PMR and GCA share similar pathogenesis. PMR is characterized by synovitis and periarthritis involving the shoulder and hip girdles, leading to pain, stiffness, and loss of range of motion of the bilateral shoulder and hip girdles. PMR can occur before, with, or after GCA. Further, 40 to 60% of GCA patients have PMR, and 15 to 20% of PMR patients have GCA.[15]

Neurological Symptoms

Up to 30% of GCA patients experience neurological symptoms. Transient ischemia or strokes, especially involving the posterior circulation, can be seen in GCA. Mononeuropathies or peripheral neuropathies can also be seen, especially C5 nerve root involvement, leading to a loss of shoulder abduction. Notably, GCA does not affect intra-cerebral arteries.

Respiratory Symptoms

Up to 10% of patients with GCA experience dry or a productive cough (w or without sputum), sore throat, or hoarseness of voice. Throat pain can also occur due to pharyngeal ischemia.

Extracranial Symptoms

10-15% of cases of GCA have extracranial involvement, including the thoracic or abdominal aorta and its branches, including the carotid, subclavian, axillary, and brachial arteries. Lower extremity arterial involvement is less common. Extracranial involvement may occur in association with cranial involvement or even in the absence of cranial involvement. Up to 50% of these patients do not have the typical cranial symptoms and have a negative temporal artery biopsy. Involvement is usually unilateral but can be bilateral. Initial symptoms are upper extremity claudication, bruits, lack of pulses in upper extremities, asymmetric pulse and blood pressure readings in upper extremities, and Raynaud's phenomenon with or without digital ischemia/gangrene. Eventually, aortic aneurysms, thoracic, more commonly than abdominal aortic aneurysms, may form, although dissection is rare.[16]

Evaluation

Laboratory Evaluation

Marked elevation in acute phase reactants is the hallmark of giant cell arteritis. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is usually elevated, although normal ESR has been reported in biopsy-confirmed cases of GCA. In steroid-naive patients with biopsy-confirmed GCA, 90% of patients have ESR greater than 50 mm/hr, up to 10% of patients can have ESR less than 50 mm/hr, and only 3.6% of patients have ESR less than 30 mm/hr.[17] Notably, ESR levels increase with advancing age and due to the presence of other comorbidities such as anemia and chronic kidney disease. Thus, elevation in ESR is a non-specific marker in itself. C-reactive protein (CRP) is considered a more sensitive marker of inflammation in GCA, and a normal CRP carries a high negative predictive value. Elevation in both ESR and CRP provides better specificity, and normal value for both ESR and CRP is associated with decreased odds of having a positive temporal artery biopsy. Serum IL-6 levels are also elevated in GCA but are difficult to interpret due to variation with circadian rhythm.

Complete blood counts may be normal or may initially show normocytic normochromic anemia and/or thrombocytosis. Serum albumin levels can be low, and elevated alkaline phosphatase can be present. Autoantibodies such as antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and ANCAs are negative.

Histopathological Confirmation

There is no specific serological or laboratory marker for diagnosis of GCA, and temporal artery biopsy is the "gold-standard" diagnostic test for GCA and must always be performed when clinical suspicion exists. When performed correctly and timely, temporal artery biopsy has a very high yield with a sensitivity of 90 to 95%. Only 5 to 10% of patients with negative bilateral temporal artery biopsy are later proven to have GCA and usually are cases with extra-cranial involvement such as aortitis.[18] Conversely, up to 50% of patients with extracranial GCA can have a negative temporal artery biopsy.

Timing of Biopsy

Biopsy shall be performed earliest possible after suspicion of GCA has been raised. However, given the risk of irreversible visual loss, treatment with corticosteroids shall not be delayed in cases with high clinical suspicion. The yield of biopsy is still very high until 2 weeks after initiation of corticosteroids. In such cases, after prompt initiation of corticosteroids, temporal artery biopsy shall be performed within 2 weeks.[19]

Procedural Considerations

In patients with headaches, the biopsy shall be performed first on the symptomatic side. The frozen section of the specimen can then be evaluated immediately evaluated, and if positive, no further biopsy is indicated. In cases with negative unilateral biopsy frozen section, the contralateral side shall be biopsied. The second biopsy can increase the yield by 5 to 14%.[20] Due to the presence of "skip-lesions" in GCA, a longer segment of 4 to 6 cm shall be excised, and the pathologist shall examine multiple segments.

Biopsy Interpretation

As mentioned above, negative bilateral temporal artery biopsy is very rarely associated with GCA when performed accurately and promptly. If suspicion still exists, further imaging studies such as angiography and evaluation of extracranial vasculitis are options. The absence of giant cells can be seen in up to 50% of cases of GCA and therefore does not exclude this diagnosis. More sensitive pathology features include lymphocytic and macrophage infiltration, disruption of the internal elastic lamina, luminal narrowing, and intimal proliferation. The presence of fibrinoid necrosis shall prompt a search for alternate diagnoses such as ANCA-associated vasculitis.

Imaging

Imaging of blood vessels has gained importance, especially in patients with extracranial GCA, 50% of whom can have negative temporal artery biopsies. Several imaging modalities have been utilized, including conventional angiography, computed tomography angiography (CTA), and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). Evaluation of the aorta and its branches, including the subclavian, axillary, vertebral, and carotid arteries, shall be pursued. Typical imaging findings are long-segment luminal narrowing with smooth tapering at the ends.

Color doppler ultrasonography is an evolving modality given the ease of performing and lack of radiation exposure. However, it is heavily user-dependant, and there is a lack of expertise in physicians to perform this test at most centers. The classic "hao sign" reveals a dark halo around the temporal artery lumen and has a sensitivity of 69% and specificity of 82%.[21][22]

The utility of other imaging modalities such as MRI with vessel wall enhancement and FDG-PET is debatable but can be considered in rare cases with strong clinical suspicion and negative temporal artery biopsy.

Classification Criteria

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has developed a set of criteria for diagnosing temporal arteritis.[23] Three of the five criteria must be present to make the diagnosis. These include:

- Age greater than or equal to 50 at the onset of symptoms

- New headache

- Temporal artery abnormalities such as tenderness of the superficial artery or decreased pulsation

- ESR greater than or equal to 50 mm/hr

- Abnormal artery biopsy, including vasculitis, a predominance of mononuclear cell infiltration or granulomatous inflammation, or multinucleated giant cells.

It must be noted that while these criteria can help diagnose GCA, they are developed for research purposes, and a clinical diagnosis of GCA shall not be made or excluded solely based on these criteria.

Treatment / Management

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids stay the main modality of treatment to date and have been shown to prevent blindness and suppress disease activity. The main goal of treatment is to prevent visual loss, which is irreversible. Initiation of corticosteroids shall be considered as soon as possible in suspected cases.

Dosing

Early treatment with a daily divided dose of prednisone 1mg/kg/day or 40 to 60 mg/day (or equivalent) in divided doses is adequate in most cases. This dose shall continue until all the symptoms resolve and acute phase reactants normalize, usually taking 2 to 4 weeks.[24] Subsequently, the dose can be decreased by 10% of the total dose every 2 weeks until the daily dose of 10 mg is reached. Thereafter, tapering shall be by 1mg every month. Alternate-day dosing of corticosteroids is not recommended. Faster tapering of steroids is usually associated with more relapses. Even with the slow tapering, relapses are common and seen in up to 50% of cases and can be associated with recurrence of symptoms and elevation in CRP. The dose of prednisone can be increased by 10mg from the dose during relapse, and once relapse resolves, tapering can resume with careful monitoring.

Duration

Almost all patients with GCA need corticosteroids for more than 1 year, and some may need long-term low doses of corticosteroids.

Role of Intravenous (IV) Corticosteroids

The role of initial IV pulse steroids (1000 mg methylprednisolone for 3 days) is debatable. One study did show the use of pulse steroids to be associated with more rapid tapering of steroids and more patients being steroid-free eventually.[25] The efficacy of IV pulse steroids in preventing contralateral vision loss in a patient with unilateral vision loss is not well established; however, due to this feared outcome, IV pulse steroids are usually used and recommended in patients with GCA presenting with unilateral vision loss.

Tocilizumab

IL-6 levels are significantly elevated in patients with GCA, and IL-6 is thought to play a pathogenic role in GCA by activating the T-cells and promote IFN-gamma release from the T-cells. Tocilizumab, an IL-6 inhibitor, was evaluated in a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial and was associated with relapse-free survival in 85% of patients in the tocilizumab+corticosteoid arm compared to 20% in placebo+corticosteroid arm by week 52.[26] In another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, sustained steroid-free remission was observed in more than 50% of patients treated with tocilizumab and corticosteroids for 26 weeks compared to 14% of those treated with corticosteroids for 26 weeks and 18% of those treated with corticosteroids for 52 weeks.[27] Further, relapses were seen in 23% of those treated with tocilizumab compared to 68% of those treated with corticosteroids.

Tocilizumab has gained significant importance in the treatment of GCA, especially in patients who are intolerant to corticosteroids. However, unanswered questions about the timing of initiation, duration of therapy, and planning of treatment tapering exist and need further investigation.

Methotrexate

While one study showed the potential steroid-sparing efficacy of methotrexate in GCA, another study failed to reciprocate these results.[28][29] The role of methotrexate in GCA is debatable, and with the advent of tocilizumab, methotrexate use is generally not recommended for GCA.

Aspirin

Low dose aspirin was associated with a reduction in rates of vision loss and strokes in GCA and can be considered as adjuvant therapy if no contraindications exist.[30]

Other Agents

Several other agents have been studied, and unfortunately, not shown to be efficacious in GCA. The use of statins was not associated with steroid dose reduction or change in the disease course.[31] Other agents, including tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, antimalarials, and cytotoxic agents, have not shown efficacy in GCA.

Other Treatment Considerations

Patients with GCA require moderate to high doses of corticosteroids for several months, which is associated with bone loss. Baseline bone density scan and treatment with bisphosphonates shall be strongly considered to prevent steroid-induced osteoporosis and fractures. Vitamin D deficiency, if present, shall be corrected. Pneumocystis jiroveci prophylaxis with sulphamethoxazole, atovaquone, or pentamidine in patients on prednisone doses of more than 5 mg/day shall be considered. Patients shall be counseled to quit smoking. Appropriate management of diabetes mellitus and hypertension, which can be accelerated by high-dose corticosteroid treatment, is important.

Differential Diagnosis

There can be several non-vasculitic disorders associated with unilateral or bilateral vision loss. In the elderly population, atherosclerosis and thromboembolism have to be considered. Infections such as bacterial endocarditis, tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus can mimic symptoms and laboratory findings of GCA. Malignancies such as lymphoma and myeloma can be associated with constitutional symptoms, arthralgia, and elevated acute phase reactants. Other vasculitis disorders, especially ANCA-associated vasculitis, can be differentiated by the absence of fibrinoid necrosis on temporal artery biopsy and lack of serological markers in GCA. Finally, amyloidosis shall be considered as it can also cause jaw claudication, and congo-red staining of the biopsy can help diagnose amyloidosis.

Prognosis

GCA is a systemic disease of variable presentation and duration. In some patients, it has a course of a few years, while in others, the course is more chronic. The majority of the patients are able to taper and discontinue the corticosteroids after a few years of the disease onset, but some may require long-term use of low-dose corticosteroids. However, GCA does not affect the overall survival rate of an individual except for those patients with aortitis and aortic dissection involvement.[32]

Complications

The most feared complication of giant cell arteritis is irreversible vision loss. Other complications include aortic aneurysms, which can rarely rupture, and cerebrovascular events in the vertebrobasilar distribution.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Giant cell arteritis is a chronic systemic disorder. Interprofessional care is needed for the best management of the patients—close collaboration between the patients' primary care physician, rheumatologist, ophthalmologist, and neurologist. Long-term use of corticosteroids, which is the cornerstone of GCA management, correlates with several adverse effects, which need to be promptly addressed. Close monitoring with laboratory and clinic evaluations can be crucial in managing GCA and its relapses and preventing GCA-induced and treatment-induced complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of temporal arteritis is with an interprofessional team that consists of an internist, neurologist, rheumatologist, ophthalmologist, nursing staff, pharmacist, and surgeon. Education is the essential step as patients need to know the complications of this disorder and the need for close monitoring related to both the condition and its treatment. All patients should be urged to follow up with an ophthalmologist to ensure that vision loss is not occurring. Anyone with weakness, loss of vision, difficulty with gait, dysphagia, or speech problems should immediately seek medical assistance. The pharmacist should educate the patient on corticosteroid compliance and the potential side effects. Nursing will often be the patient's first point of contact for questions and can also coordinate activities and information sharing between the various disciplines involved in care. All patients should understand that they may develop problems with other blood vessels in the future despite treatment.[33][34] [Level 5]

Outcomes

For the majority of patients, who get prompt treatment, there is a complete recovery. Symptomatic improvement occurs in 2 to 4 days after treatment. To avoid the adverse effects of the corticosteroids, tapering is recommended after 4 to 6 weeks. Blindness from temporal arteritis is very rare today. However, the course of the disease does vary from patient to patient and may last 3 months to 5 years. The biggest problem with the treatment of temporal arteritis today is the morbidity associated with corticosteroids. Thus, nursing should be familiar with and monitor for these adverse events and report them to the team if present. Individuals likely to require prolonged treatment with steroids include females, older age, and those with a higher baseline ESR. The prognosis is poor for untreated individuals; these individuals may have blindness, develop a stroke, or an MI. Overall, about 1 to 3% of patients with temporal arteritis die from a stroke or an MI.[35]