Continuing Education Activity

Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency is a clinically under-recognized genetic disorder that causes the defective production of alpha-1 antitrypsin protein. AAT protein protects the body from the neutrophil elastase enzyme, which is released from white blood cells to fight infection. This activity discusses the evaluation and management of AAT and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing and treating the disease to improve patient care.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology and epidemiology of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- Explain the common physical exam findings associated with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- Outline the evaluation and management options available for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- Explain the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to ensure prompt diagnosis of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency to optimize patient management.

Introduction

Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) deficiency is a clinically under-recognized genetic disorder that causes the defective production of alpha-1 antitrypsin protein. AAT protein protects the body from the neutrophil elastase enzyme which is released from white blood cells to fight infection. This inherited disorder leads to decreased AAT activity in the blood and lung and deposition of excessive abnormal AAT protein in the liver.

Both deficiency and an abnormal form of AAT are due to mutations in the SERPINA1 gene. Without enough functional AAT, neutrophil elastase destroys alveoli and causes lung disease. Abnormal AAT can also accumulate in the liver and cause damage to this organ. People with AAT deficiency usually develop the first signs and symptoms of lung disease between ages 20 and 50. It is well-documented that the rate of decline in lung function is strongly dependent on cigarette smoking.[1][2][3]

Etiology

AAT deficiency is inherited by the autosomal co-dominant transmission which means that affected individuals have inherited an abnormal AAT gene from each parent. The gene that encodes AAT is called SERPINA1 and is located on the long arm of chromosome 14.

At least 150 alleles of AAT (SERPINA1) have been identified, and each has a letter code based upon electrophoretic mobility of the protein produced. The normal allele is referred to as “M,” and it is the most common version (allele) of the SERPINA1 gene. Most people in the general population have two copies of the M allele (MM) in each cell. Other versions of the SERPINA1 gene lead to reduced levels of alpha-1 antitrypsin. For instance, the S allele produces moderately low levels of this protein, and the Z allele produces very little AAT. Individuals with two copies of the Z allele (ZZ) in each cell are likely to have AAT deficiency. Those with the SZ combination have a higher risk of developing lung diseases (such as emphysema), particularly if they smoke.

Worldwide, it is estimated that 161 million people have one copy of the S or Z allele and one copy of the M allele in each cell (MS or MZ). Individuals with an MS (or SS) combination usually produce enough alpha-1 antitrypsin to protect their lungs. People with MZ alleles have a slightly increased risk of impaired lung or liver function.

AAT phenotypes are based on the electrophoretic mobility of the proteins produced by the various abnormal AAT alleles. Genotyping is performed by identifying specific alleles in DNA.

Based on this, variants of AAT can be categorized into four basic groups:

- Normal that is associated with normal levels of AAT and normal function. The family of normal alleles is referred to as M, and the normal genotype is MM.

- Deficient that is associated with plasma AAT levels less than 35% of the average normal level. The most common deficient allele associated with emphysema is the Z allele, which is carried by about two to three percent of the Caucasian population in the United States.

- Null alleles that lead to no detectable AAT protein in the plasma. Individuals with the null genotype are the least common and are at risk for the most severe form of associated lung disease but not liver disease.

- Dysfunctional alleles produce a normal quantity of AAT protein, but the protein does not function properly.

Environmental factors, such as exposure to tobacco smoke, chemicals, and dust, likely impact the severity of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

Severe deficiency of AAT has a strong risk factor for early-onset emphysema, but not every severely deficient individual would develop emphysema. Risk factors for emphysema include cigarette smoking, dusty occupational exposure, parental history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and a personal history of asthma, chronic bronchitis, or pneumonia.

Epidemiology

AAT deficiency occurs worldwide, but its prevalence varies by population. This disorder affects about one in 1500 to 3500 individuals with European ancestry. It is uncommon in people of Asian descent.

Although AAT deficiency is considered to be rare, estimates that 80,000 to 100,000 individuals in the United States have a severe deficiency of AAT suggest that the disease is under-recognized. It is estimated that more than three million people worldwide have allele combinations associated with severe deficiency of AAT.[4][5]

Pathophysiology

Emphysema in AAT deficiency is considered due to an imbalance between neutrophil elastase in the lung. This destroys elastin, and the elastase inhibitor AAT, which protects against proteolytic degradation of elastin. This mechanism is known as a “toxic loss of function.” Specifically, cigarette smoking and infection increase elastase production in the lung, therefore increasing lung degradation. Also, the polymers of “Z” antitrypsin are chemotactic for neutrophils, which may contribute to local inflammation and tissue destruction in the lung.

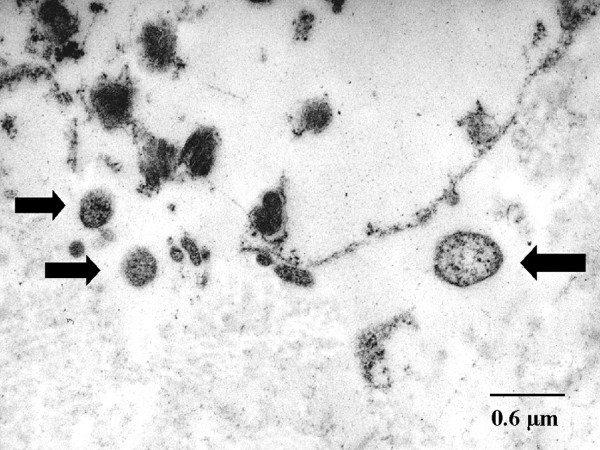

The pathogenesis of the liver disease is different and is called a “toxic gain of function.” The liver disease results from accumulation within the hepatocyte of un-secreted variant AAT protein. Only those genotypes associated with pathologic polymerization of AAT within the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes produce disease. Most patients are homozygous for the Z allele (i.e., PI*ZZ); liver disease does not occur in null homozygotes who have severe AAT deficiency but no intra-hepatocytic accumulation.

History and Physical

The main clinical manifestation of AAT deficiency is related to the involvement of three separate organs: the lung, the liver, and, rarely, the skin.

Clinical presentation of lung diseases, namely emphysema due to AAT deficiency, has many features in common with usual COPD. Dyspnea is the most common presenting symptom, and many patients have a cough, sputum production, and wheezing, either chronically or with upper respiratory tract infections. Spontaneous secondary pneumothorax may be the presenting manifestation of AAT deficiency, or it may be a complication of the known disease. Bronchiectasis has also been associated with a severe deficiency of AAT.

Clinical presentation of extrapulmonary disease in patients with at-risk alleles (e.g., Z, S[iiyama], and M[malton]) may develop adult-onset chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Other extrapulmonary manifestations of AAT deficiency include necrotizing panniculitis, hot, painful, erythematous nodules, or plaques on the thigh or buttocks that are the major dermatologic manifestation of AAT deficiency. Others are systemic vasculitis, psoriasis, urticaria, angioedema, and possibly inflammatory bowel disease, intracranial and intra-abdominal aneurysms, fibromuscular dysplasia, and glomerulonephritis.

Evaluation

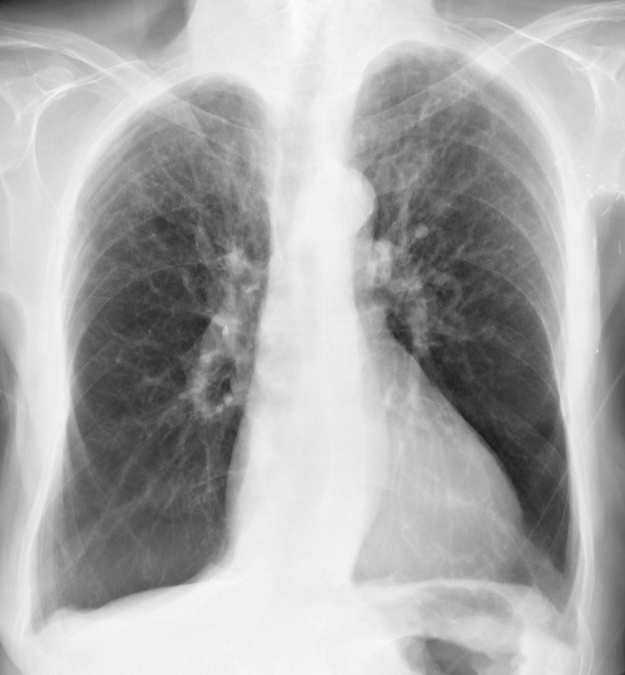

Imaging: A chest x-ray is used to determine the pattern and extent of emphysema and exclude other causes of dyspnea. The “classic” pattern of emphysema in AAT deficiency is basilar predominant emphysematous bullae, although a range of patterns from basilar predominant to apical predominant emphysema may be seen. Some clinicians perform chest computed tomography (CT) scans for an initial assessment.[6][7]

- Bronchodilator responsiveness (defined as a post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] rise of 200 mL and 12%) is common.

- Pulmonary function testing is used to assess the presence and severity of lung disease. Spirometry is typically obtained before and after bronchodilator, lung volumes, and diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO). If DLCO is below normal or if the patient reports exertional dyspnea, a six-minute walk test should be obtained.

- All adults with persistent airflow obstruction on spirometry should be tested for AAT deficiency, mainly those from geographic areas with a high prevalence of AAT deficiency.

Additional features that should lead clinicians to test for AAT deficiency include:

- Emphysema in a young individual (e.g., age 45 years or younger).

- Emphysema in a person who does not smoke or smokes minimally

- Emphysema characterized by predominant basilar changes on the chest radiograph.

- A family history of emphysema or liver disease. Clinical findings or history of panniculitis

- Clinical findings or history of unexplained chronic liver disease.

The diagnosis of severe AAT deficiency is confirmed by demonstrating a serum level below 11 micromols/L (approximately 57 mg/dL by nephelometry) in combination with a severe deficient phenotype assessed by testing for the most common deficient alleles (i.e., S, Z, I, F).

If the AAT serum level is greater than 20 micromol/L, it is unlikely that the patient has a clinically significant AAT deficiency, but if we are evaluating for the presence of particular mutations, genotyping is necessary to identify heterozygotes and mutations that have incomplete penetrance.

The normal plasma concentration of AAT ranges from 80 mg/dL to 220 mg/dL (20 to 48 micromol/L using nephelometry or 150 mg/dL to 350 mg/dL by radial immunodiffusion). However, given the variability in reference ranges, patients with a serum AAT level below 100 mg/dL (18.4 micromols/L) should be evaluated further with isoelectric focusing or genotyping.

Isoelectric focusing is the gold standard blood test for identifying AAT variants and is considered a phenotype test.

Genotyping of the protease inhibitor (Pi) locus is performed on a blood sample using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology or restriction fragment length polymorphisms. These tests detect the most common known variants (F, I, S, Z). Gene sequencing of exonic DNA can be used if both tests fail to determine the genetic variant.

In monitoring asymptomatic patients, i.e., those with no respiratory symptoms and normal baseline spirometry (i.e., FEV1 80% or greater of predicted), spirometry should be repeated when symptoms change or at 6 to 12-month intervals. An unexplained decrease in the post-bronchodilator FEV1 to less than 805 predicted is an indication to initiate augmentation therapy.

Guidelines are lacking regarding monitoring for liver disease in patients homozygous for PiZ, PiS[iiyama], or PiM[malton]. It is advised to assess serum aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase, and bilirubin on an annual basis. Some clinicians also obtain a complete blood count (CBC), looking for thrombocytopenia, and an abdominal ultrasound looking for cirrhosis every 6 to 12 months.

Treatment / Management

Intravenous augmentation via the infusion of pooled human alpha-1 antitrypsin, which is an alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor. This therapy is the most direct and efficient means of elevating AAT levels in the plasma and the lung interstitium. [8][9][10][11]

The American Thoracic Society suggests weekly augmentation therapy with human pooled AAT for individuals who have plasma levels of AAT less than 11 micromols/L and established airflow obstruction, defined as an FEV1 less than 80% predicted. On the other hand, the Canadian Thoracic Society suggests keeping AAT augmentation therapy for AAT-deficient patients (AAT level less than 11 micromols/L) with an FEV1 of 25% to 80% predicted who have quit smoking and are on optimal medical therapy.

The selection criteria for augmentation therapy include:

- High-risk phenotype

- Plasma AAT level below 11 micromols/L

- Airflow obstruction by spirometry (e.g., FEV1 less than 80% of predicted)

- Likely compliance with the protocol

- Age equal to or greater than 18 years

- Nonsmoker or ex-smoker.

Augmentation therapy is not recommended for patients with heterozygous phenotypes, whose plasma AAT level exceeds 11 micromols/L.

Side effects associated with intravenous AAT infusion are uncommon, and no long-term reactions have been noted. Some side effects can occur, including:

- Low-grade fever and mild flu-like symptoms are usually self-limited.

- Anaphylaxis with IgE antibody formation to AAT has been reported, and that is extremely rare.

- A syndrome of transient fever, chest and low back pain, and thrombocytopenia has been reported. It is due to a high molecular weight contaminant in the stabilizer added to the AAT product in the late 1980s

- Pooled human plasma alpha 1-antiprotease contains small amounts of IgA so that IgA-deficient individuals with anti-IgA antibodies are at risk of anaphylaxis with current infusions. Before initiating intravenous AAT therapy, it is recommended to check for IgA deficiency or anti-IgA antibodies.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of AAT deficiency lung disease:

- Emphysema

- Chronic bronchitis

- Bronchiectasis

The differential diagnosis of AAT deficiency liver disease:

- Chronic viral hepatitis

- Hereditary hemochromatosis

- Wilson disease

- Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

Prognosis

In patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency who develop cirrhosis, the prognosis is grave.

Complications

Complications of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency include:

- Asthma

- Emphysema

- Chronic bronchitis

- Chronic liver disease

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency should be advised to quit smoking, avoid exposure to occupational dust, and have yearly influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations. This will prevent the progression of lung disease.

To prevent secondary complications related to liver disease, they should be advised to limit alcohol intake and undergo hepatitis A and B vaccinations.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

AAT is best managed by an interprofessional team of health professionals that includes a pediatrician, geneticist, pulmonologist, gastroenterologist, and internist. During the first three decades of life: liver dysfunction is a major threat to the health of affected individuals, while pulmonary dysfunction is not a major concern. Beyond the first two to three decades of life, the natural history of people with severe deficiency of AAT is less clear, and the survival estimates for subjects with severe deficiency of AAT vary among series, presumably due to differences in study populations. Relatively normal survival appears possible for nonsmoking asymptomatic individuals, although long-term follow-up in a population-based study is needed for confirmation. The FEV1 is a major determinant of survival in AAT-deficient individuals, with the mortality rising as FEV1 falls below 35% of predicted. Other parameters that are used to predict are decreased lung density as assessed by chest CT.[12][13]