Introduction

Medical standards are put in place to prevent hazards during a flight that could be caused by the physical, medical, and psychological conditions held by the pilot or the crew. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) agreed at the Chicago Convention in 1944 to standardize practices where uniformity would improve air navigation. In subsequent annexes to the original convention, the regulations that standardize personnel licensing and rules of the air were established that guide the medical requirements for pilots and aircrew today. After evaluation of available data and the potential risks at different times during a flight, ICAO set a goal of less than 1% risk of pilot incapacitation per year to guide the standards for medical examinations. Gastrointestinal issues, earaches, faintness, headache, and vertigo are the most common causes of incapacitation[1]. Less common but more dangerous debilitations such as alcohol intoxication and sudden cardiac death have been implicated in mishaps, so screening for these risks carries high importance[2][3]. Mental health is also extremely important given mishaps like Germanwings Flight 9525 and other cases of suicide by aircraft.[4] While some research has been done in the field of pilot incapacitation, there is not a significant evidence base for many recommendations, but rather it is a consensus of professional opinion. Member states, therefore, often have different interpretations of the guidelines and therefore different regulations.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) governs the standards in the United States for civilians, and the military has a separate set of directives for active-duty aviators, with military rules generally being more stringent. In general, military aviators have to be physically fit for duty as military officers as well as passing requirements for aviation. This article will discuss the major medical statutes as laid out by the FAA and any differences in requirements in the Navy, Army, and Air Force. The FAA lays out slightly different regulations for airline transport pilots and commercial pilots versus private pilots, with private pilots having less rigorous requirements. The military also distinguishes medical requirements for aviators versus aircrew or other individuals within the aviation community. All organizations have disqualifying conditions that are not conducive to aviation due to an adverse impact on safety and health, but many conditions may be considered for waiver. All initial physical exams for licensing and fitness for duty must be conducted by an Aviation Medical Examiner (AME) or its military equivalent. If the AME finds the candidate is medically disqualified, the candidate may be referred to a Federal Air Surgeon for evaluation for a Special Issuance of Medical Certificate. Air Transport Pilots require a first-class medical certificate valid for 12 months for those aged less than 40 and 6 months for those over 40. Commercial pilots and aircrew need a second-class certificate valid for 12 months for all ages. Private pilots require a third-class certificate valid for 24 months for those over 40 and 60 months for those under 30.

Issues of Concern

Disqualifying Conditions

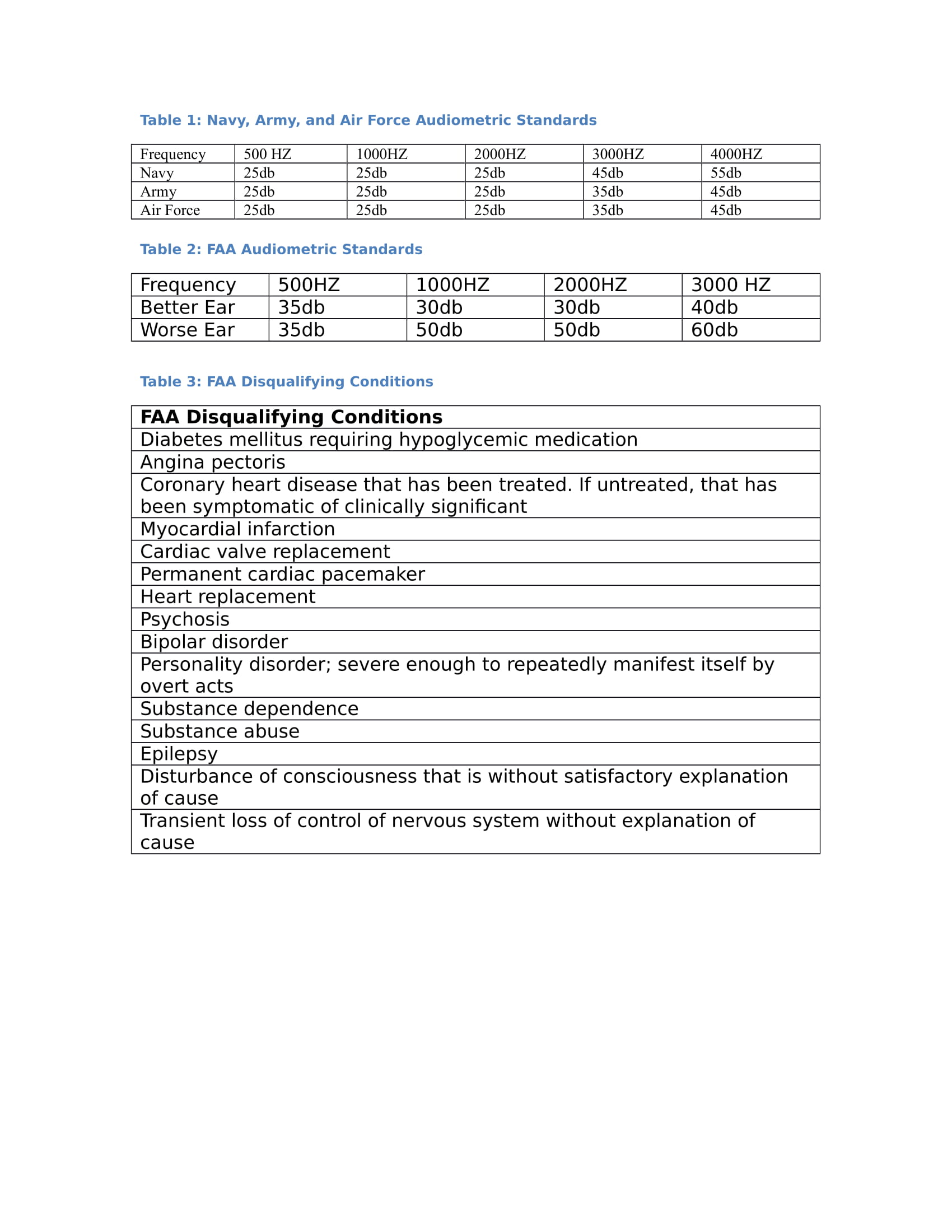

Evaluation of any pilot or pilot candidate begins with a thorough history. The FAA has multiple disqualifying conditions that are listed in the table below. The Navy, Army, and Air Force first have medical directives for any person obtaining active duty status. The disqualifying conditions below would likely also disqualify a person from becoming an active duty member of the military. The Navy states that all conditions can be considered for a waiver if personnel has met general active-duty medical standards. The Army and Air Force also have similar rules. Whether the waiver is granted is ultimately up to the authorities within the aerospace medicine division of the different branches of the military.

Table 3: FAA Disqualifying Conditions, See image

Distance Vision

The FAA regulates that all airline and commercial pilots have 20/20 or better vision in each eye with or without correction, where private pilots can have 20/40 or better with or without correction. There are no limits to how poor vision can be as long as it is corrected to 20/20. Navy standards for students state 20/40 or better uncorrected in each eye which must correct to 20/20. Other aircrew members in the Navy have no limits to vision as long as vision can be corrected to 20/20. Army regulations state that an aviator has to have 20/50 vision or better, which is correctable to 20/20. The Air Force requires the same. The Air Force states that aviators may have a refractive error between -1.50 to -3.00 for myopia, +2.00 and +3.00 for hyperopia, and 1.50 to 3.00 for astigmatism. All errors must be correctable to 20/20.

Near Vision

Near vision for all pilots, according to the FAA, should be 20/40 or better with or without correction measured at sixteen inches. The Navy directives are slightly stricter with 20/40 or better uncorrected and 20/20 with correction. The Air Force notes no standard for uncorrected vision but must correct to 20/20. Aircrew members have no restrictions with near uncorrected vision as long as near vision can be corrected to 20/20. The Army holds the same limits as the Navy.

Color Vision

The FAA states that airmen must have the ability to perceive color necessary for the safe performance of duties. Examiners must use specific color vision plates for testing, such as Pseudoisochromatic Plates (PIP). The Army also uses color vision plates to test vision. The FAA prohibits web-based color vision tests. The Navy considers PIP as the primary test for color vision, and a passing rate is interpreting 12 out of 14 plates. Computerized Color Vision tests like Waggoner CCVT, Colour Assessment & Diagnosis, and Cone Contrast Test are also approved as color vision tests within the Navy. The Air Force uses the Cone Contrast Test (CCT) as their standard test. ACCT test score below 75 for red/green vision is considered evidence of deficiency.

Ophthalmology

A slit lamp exam is required by the Navy to rule out any anatomical abnormalities in the eye. Intraocular pressure is also tested and must be below 22 mmHg with a minimum of 4 mmHg difference between eyes.

Hearing

The Navy, Army, and Air Force have stricter requirements on hearing than that of the FAA. All military aviators and crew have to pass an audiometric exam. With the FAA, a pilot can demonstrate good hearing with an audiometric test or through a basic hearing exam in an exam room. The FAA states that a pilot has to demonstrate hearing of a conversational voice in a quiet room at a distance of six feet with both ears with his back turned to the examiner.

Audiology

The audiometric limits for the military are once again more demanding than the FAA standards for student pilots. Standards can be waived to FAA levels (with exception of hearing at 30db at a frequency of 100HZ) depending on the type and severity of hearing loss and the ability to hear warning tones and radio transmissions in the cockpit.

Table 1: Navy, Army, and Air Force Audiometric Standards (see image)

Table 2: FAA Audiometric Standards, See image

ENT

The FAA does not allow any ear condition that causes vertigo, a disturbance of equilibrium, or speech. The military branches have many more ENT conditions that are discussed in all of the regulations, but waivers are not granted for conditions that cause the above deficits. These conditions include Meniere disease and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Conditions such as chronic sinusitis, cleft palates (not able to be repaired with surgery), or any condition that inhibits speech are disqualifying for aviators as well.

Pulse

The FAA states that a pulse rate of less than 50 is disqualifying, but with no sign of underlying coronary artery disease, they may still obtain a certificate. The Navy notes that the pulse must be less than 100 and greater than 45 but if less than 45, the anomaly can be waived if appropriate cardiac response to exercise is noted. The Army has no lower limit so long as the candidate is asymptomatic. The Army notes persistent tachycardia greater than 100 is disqualifying. The Air Force sets no rate limits, but various arrhythmias are disqualifying.

Blood Pressure

The FAA allows for a pilot to be more hypertensive than all of the military branches. The maximum blood pressure value for the FAA is 155/95 mmHg, whereas blood pressure is not to exceed 140/90 for the military. If a diagnosis of hypertension is made, the FAA has approved alpha-blockers, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), direct renin inhibitors, direct vasodilators, and thiazide diuretics. The aviator is required to be grounded for seven days when initiating the approved medications to rule out any side effects. The Navy states that all hypertension medications are downing for flight except ACE-I, ARBs, thiazide diuretics (HCTZ only), and calcium channel blockers (amlodipine only), which are forgone due to limited side effects. When initiating a medication, the aviator must be downed for 30 days to prove blood pressure control and no evidence of side effects. The Air Force does not require a waiver for hypertension if blood pressure is controlled via lifestyle modifications or monotherapy with a thiazide diuretic, ACE-I or ARB.

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

An ECG is required at age thirty-five and annually after the age of forty, according to the FAA. The Navy requires an ECG every five years from the age of twenty-five and annually after the age of fifty. Common variances include sinus bradycardia, first-degree AV block, and incomplete right bundle branch block.[5] These are considered normal in young and otherwise healthy aviator and aircrew members. Per the Air Force, Mobitz II second-degree AV block and third-degree block are disqualifying for all applicants with no chance of waiver. Further information can be found in the StatPearls article specifically written for the cardiology portion for fitness for duty.

Mental Health

Per the FAA, any diagnosis of psychosis, bipolar disorder, or severe personality disorder is disqualifying. Severe depression with suicidal ideations or a suicide attempt or requiring multiple medications is disqualifying. There are considerations for minor depressive disorders, anxiety, and grief. Aviators may be granted a certificate if entirely off of medication, completion of psychotherapy, and stable for six months. FAA regulations state that individuals on monotherapy with specific SSRIs ( fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram) for major depression for an extended period may be granted a waiver if they have medical proof of stability for at least six months.

Psychiatric disorders in any military aviation community are generally disqualifying, but all disorders may be considered for waiver. For example, if a member has been diagnosed with attention deficit disorder in the past but has been off medication for twelve months without issue, they may obtain a waiver. Overall, the use of all psychotropic medications, including SSRIs, is disqualifying. All military aviators must be off of all prescriptions and have stopped psychotherapy from being considered fit for duty. Generally, diagnoses of psychosis, bipolar disorder, or personality disorder are not granted waivers in aviation and sometimes require a medical discharge from the military as a whole since the use of antipsychotic medication, and routine psychiatric evaluation is disqualifying for duty.

Substance Dependence and Use

The FAA states that a diagnosis or medical history of substance dependence is disqualifying unless there is clinical evidence of total abstinence for the preceding two years. Substances include alcohol and other drugs, for example, opioids, amphetamines, marijuana, and cocaine. Substance use may be identified by case history with an appropriate medical review, the use of a substance in a physically hazardous situation, a positive drug test or alcohol level greater than 0.04 on a Department of Transportation required a drug test, or a refusal to complete a Department of Transportation drug test. There is currently no duty to report a known pilot identified with substance abuse disorder or other substance-related diagnoses if they present for care in emergency rooms.

Pharmaceuticals

The different military branches and the FAA have a list of pharmaceutical agents that can down an aviator permanently or for the period that the person is using a specific drug. The list of these medications is readily available on the FAA website. There are two basic categories of medications Do Not Issue and Do Not Fly. An airman may not receive a medical certificate if they are on a Do Not Issue medication such as angina medicines, seizure medicines, anticholinergics, hypoglycemia inducing diabetes medicine, centrally acting antihypertensives, and others. Do Not Fly drugs may be taken temporarily, but pilots are not to supposed to fly until a certain period after taking them. The period is defined as five times the half-life. Or if the half-life is unknown five times the maximum time interval. For example, if a patient is taking a medication on the list every six to eight hours, then the downtime would be 40 hours or five times the maximum interval of 8 hours. Other medications may have a specific downtime; for example, the acne medicine isotretinoin must be ended at least two weeks before flying due to concern for visual and psychiatric side-effects. Multiple other medications have specific guidelines and are available in the FAA guide. The waiver guides for the separate military branches also have a list of medicines that are temporarily downing. The military restrictions are much more severe, and therefore there are many more medications that are temporarily downing when compared to FAA guidelines. For example, in the Navy, nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are temporary downing, but erythromycin is not. All nasal decongestants are downing, but non-sedating antihistamines, such as loratadine, may be used.

Clinical Significance

All aviators, whether civilian or military, have to meet certain medical standards to help prevent potential incapacitation and provide for a safe flight environment. While an AME will complete medical exams for certification, pilots and aircrew may present to emergency rooms, urgent care, and outpatient clinics for acute issues. It is essential that providers are aware of the basics of flight fitness and the implications of specific diagnoses and medications. This article outlines basic guidelines for an assessment of fitness for duty, but complete information is available in the specific guides for the regulating body. Overall the guidelines set by the FAA are similar to those established by the military. However, military instructions are overall more demanding. The different military branches each have some particular differences but, in general, are similar requiring, both fitness for active duty and flight status. This article only covers a fundamental review of everything that should be included in an assessment of duty exam, but all the organizations discussed have guidelines available online to help medical examiners with an estimate of duty physicals. The instructions also contain extensive examples of what is abnormal and what may be granted a waiver. These guidelines should be used for every pilot and aircrew member.

All standards discussed above were laid out by the FAA, Navy, Army, and Air Force. The following regulations can be found as separate documents online.

ICAO Manual of Civil Aviation Medicine

FAA: Guide for Aviation Medical Examiners

Navy: Aeromedical Reference and Waiver Guide

Air Force: Waiver Guide

Army: Regulation 40-501