Continuing Education Activity

Tracheal trauma may be penetrating or blunt and acute or subacute. A blow or stab wound to the neck or crush injuries to the upper chest may cause acute traumatic disruption of the trachea, as can subacute insults, such as overinflation of an endotracheal tube (ETT) cuff pressing against the internal tissues of the trachea over time. Blunt trauma to the neck may result in shearing of the trachea, usually within 3 cm of the carina. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of tracheal trauma and highlights the role of interprofessional team members in collaborating to provide well-coordinated care and enhance patient outcomes.

Objectives:

- Identify when tracheal trauma should be considered.

- Review injuries commonly seen in conjunction with tracheal trauma.

- Describe the management options for tracheal trauma.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies for improving

coordination and communication to advance the management of tracheal trauma and improve outcomes.

Introduction

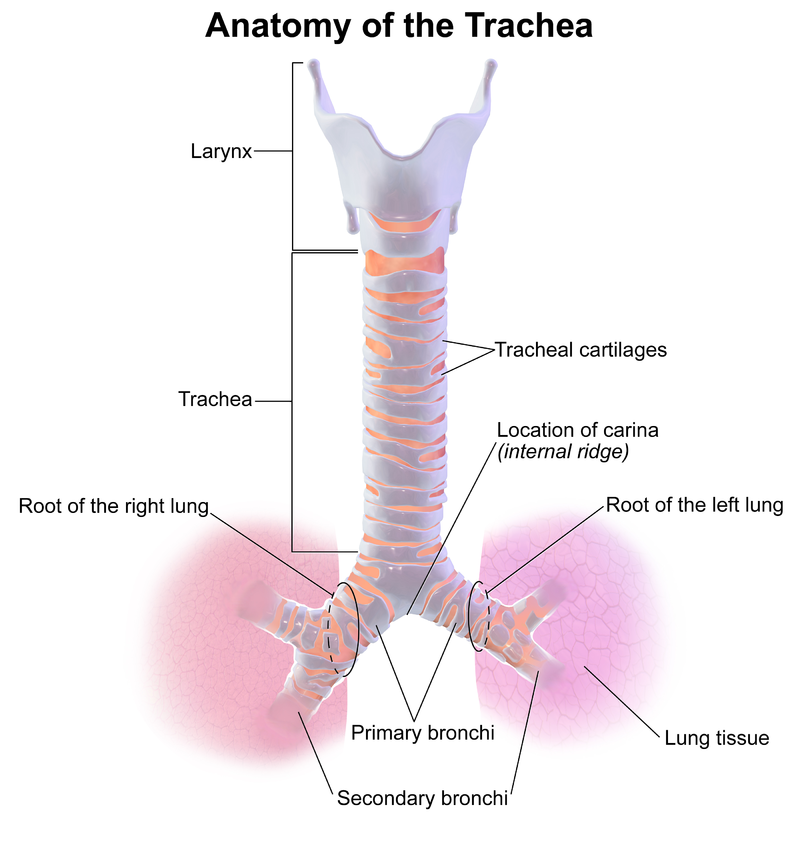

The trachea is a cartilaginous tube that courses through the neck and upper chest to connect the pharynx and larynx to the lungs. The trachea bifurcates at the carina into the right and left primary bronchi, via which inspired air is delivered to lung tissue, and expired out. The study of tracheal injury is often combined with adjacent airway structures (tracheobronchial trauma, laryngotracheal trauma). See image below.

Trauma to the trachea may be penetrating or blunt and acute or subacute. A blow or stab wound to the neck, or crush injuries to the upper chest, may cause acute traumatic disruption of the trachea, but subacute insults also occur (e.g., from an overinflated endotracheal tube [ETT] cuff pressing against the internal tissues of the trachea over time). Blunt trauma to the neck may result in shearing of the trachea, usually within 3 cm of the carina.[1] Depending on the mechanism, tracheal trauma may be associated with trauma to nearby structures including bony disruptions of the cervical spine, vascular injury to the great vessels, carotids, or jugulars, or digestive tract involvement. Regardless of the mechanism, early diagnosis and surgical repair are crucial to reducing complications and loss of respiratory function.[2]

Etiology

Tracheal trauma may follow from either cervical or thoracic injury; cervical injuries tend to be more visible and obvious; thoracic injury may go unnoticed. When there is an injury to the tracheobronchial tree, a bronchial injury is more common, especially in blunt trauma where shearing forces may act on the relatively fixed bronchial structures and disrupt them.[2]

Trauma to the trachea may be classified as either penetrating or blunt. Penetrating injuries to the neck and chest should always raise suspicion of, and prompt investigation of, potential tracheal trauma.

Blunt trauma to the trachea may result from direct blow (including compression/strangulation), severe neck flexion or extension injuries, or crush injuries to the chest (MVC most common). An endotracheal injury may result from inhalation or exposure to noxious or hot gas, vapor or fumes, or from foreign body aspiration. Iatrogenic causes of injury include intubation and tracheostomy (especially with positive pressure ventilation or an overinflated ETT cuff) as well as cricothyrotomy attempts. It should be noted that blunt trauma resulting in tracheal injury often causes other thoracic and cervical injuries.[3]

Epidemiology

Overall, a tracheobronchial injury is relatively uncommon in blunt trauma (less than 1% of hospitalized blunt trauma patients have this type of injury). However, the majority of tracheal injuries are due to blunt trauma including direct blows, compression or strangulation, and shearing injuries (e.g., clothesline injuries) from sudden flexion, extension or deceleration. Blunt trauma accounts for 60% of external laryngeal injuries. Approximately two-thirds of upper airway injuries involve the cervical trachea, while the remaining one-third are laryngeal injuries. While penetrating trauma to the trachea is also relatively uncommon, it is the most common airway structure injured by stab wounds to the neck. When found, it is more frequently seen in patients with concomitant cervical trauma and vascular or digestive tract injuries. In fact, when death results from this type of penetrating trauma, it is most commonly associated with concomitant vascular injury rather than the airway injury itself. Failed or flawed intubation attempts are another potential cause of death in this population. It should also be noted that most injuries requiring tracheal reconstruction are iatrogenic and related to tracheostomies and endotracheal intubation. The most common among these are tube cuff injuries.[1]

The thyroid cartilage is the tracheal structure most commonly fractured in both blunt and penetrating trauma. In blunt trauma, tracheal transection most commonly occurs distal to the cricoid cartilage and within 3 cm of the carina.

Up to 25% of patients with acute laryngotracheal trauma requiring surgery have no physical evidence of the injury at initial presentation, and signs may be delayed for 24 to 48 hours. A high index of suspicion is necessary to avoid missing an occult injury as delays in diagnosis and definitive treatment are associated with poorer outcomes. Mortality is relatively high in patients with acute trauma to the trachea with a reported 15% to 40% range depending on mechanism and classification.[4]

Pathophysiology

Tracheal disruption may involve tracheal cartilages (most commonly from direct, blunt trauma). Alternatively, tracheal tears or laryngotracheal separation may result from shearing forces in flexion/extension injuries. Chest crush injuries may cause sagittal tears of the membranous portions of the trachea and bronchi, often due to compression of the structures between the manubrium or sternum and vertebral column. See image below.

Injury types include laryngotracheal contusions, lacerations, hematomas, avulsions, and fracture/dislocation of the tracheal cartilages. In rare cases, a complete transaction of the trachea may occur.

History and Physical

Symptoms and signs range from mild (blood tinged sputum) to severe with frank hemoptysis, shortness of breath, dysphagia, and cyanosis. Hoarseness is the presenting symptom in 85% of cases.

On physical exam, pertinent findings include stridor, cyanosis, dyspnea, voice changes/hoarseness, subcutaneous emphysema, mediastinal crunch on auscultation. The absence of these findings does not exclude tracheal injury, as many of these patients may not have symptoms in the first 24 to 48 hours.

Evaluation

The initial approach in the emergency department, as always, is directed to the ABCs (Airway, Breathing, and Circulation). If signs of airway injury are present, ensuring and protecting airway patency are of paramount importance. There should be a low threshold for definitive airway management when a tracheal injury is suspected, as there is a significant risk of rapid progression of edema, and the patient may be required to lay supine which may further compromise their airway. Endotracheal intubation may be attempted, but a double set-up (with cricothyrotomy supplies at the bedside) is advisable. Because often there is a concern about induction and paralysis collapsing airway structures, awake intubation should be considered.[1]

Other adjunctive measures include suction of secretions to prevent aspiration and enhance ventilation, and oxygen supplementation as needed. Intravenous (IV) access should be secured, and fluid resuscitation started if indicated.

The diagnosis of tracheal trauma may be made by cervical or chest radiography, cervical or chest computed tomography (CT), or bronchoscopy. If a tracheal injury is suspected, CT of the neck and chest with IV contrast should be performed. Up to 70% of patients with acute tracheobronchial injury will have a pneumothorax; 60% will have pneumomediastinum and cervical emphysema. While chest CT is superior to radiographs in diagnosis, it may still yield false negatives due to adjacent edema, hemorrhage or secretions. CT has the added advantage of diagnosing injuries to adjacent structures including sternal fractures and mediastinal hematomas, as well as vascular disruptions when IV contrast is used. Concomitant injuries to the great vessels and esophagus (25% of penetrating upper airway injury), as well as cervical spine injuries (10% to 50% of patients with blunt airway injury), may be diagnosed via CT.

A patient with a potentially unstable unsecured airway should not be placed in a CT scanner as a supine position will increase the risk of airway collapse.

Treatment / Management

Conservative management is appropriate for mild injuries (less than 2 to 3 cm mucosal lacerations, involving less than one-third diameter, no other injury, stable patent airway and breathing, mild symptoms/signs). Humidified oxygen is given and the patient observed in a critical care setting for deterioration. Antibiotic prophylaxis is indicated.

If the airway is compromised, intubate early. The ETT may have the added benefit of stenting a partially collapsed trachea, and possibly tamponading or bridging acute tracheal disruptions with severe air leaks. Most patients can be managed with orotracheal intubation, but double set-up with preparation for surgical airway is advisable as unsuspected cricoid cartilage injury may convert a partially occluded airway into a completely occluded airway, particularly when an unsuspecting assistant gives the patient cricoid pressure. While rapid sequence intubation (RSI) may be performed, awake intubation should be considered in this patient population. Induction or paralysis may cause a partially stented airway to collapse potentially precluding both intubation and ventilation. Ideally, preoxygenation would be followed by awake intubation; positive pressure ventilation should only be started once the tube is past the injury (sometimes necessitating bronchial intubation) and neuromuscular blockade should follow the airway being secured. Patients with severe open cervical disruptions, especially in penetrating injury, may be intubated by guiding an ETT through the open wound. This may be preferable in fact as it spares otherwise intact tissue from being disrupted for a surgical airway, and facilitates subsequent repair.[5]

Inhalation injuries should also be managed with early and aggressive intubation (with escalation to cricothyroidotomy or tracheostomy as needed) due to risk of rapid deterioration from laryngeal edema.

In cases of thoracic injury and pneumothorax, a chest tube should be inserted, ensuring that there is lung reexpansion without persistent air leak. When there is coexisting severe pulmonary parenchymal injury, and severe persistent air leak, pneumonectomy may be considered.

Surgical repair of tracheal trauma may include repair of lacerations, reduction and closure of fractured cartilages, and potentially end to end anastomosis if complete transection has occurred.

When the injury is in the proximal two-thirds of the trachea, repair involves a cervical incision and endolaryngeal approach. The anterior neck muscles are dissected, revealing tracheal cartilages; a midline thyrotomy is then performed to reveal the endolarynx allowing for repair of mucosal lacerations, closed with chromic sutures. If indicated, a laryngeal stent may be inserted and secured in place. When the laryngeal cartilages are fractured, stabilization and fixation may be aided by plating, which reduces movement of the fractured fragments and inflammation. Four-point fixation is utilized to hold the plate in place. For complete transection of the trachea, following immediate airway rescue through a tracheostomy, the cricoid cartilage (if fractured) is repaired first. Primary re-anastomosis is then performed using absorbable sutures to repair the mucous membrane, while non-absorbable sutures are placed from the superior cricoid ring to the inferior portion of the first or second tracheal ring to distribute tension away from the anastomosis. Stenting may also be considered.[5]

Surgical exploration should occur within 24 hours of the injury to minimize subsequent scarring and airway stenosis. For similar reasons, if endolaryngeal stenting is used in the repair, it should be removed within 10 to 14 days.

Differential Diagnosis

- Digestive tract (esophageal) injury

- Other causes of hypoxia and dyspnea including pneumothorax, pulmonary contusion or laceration

- Airway obstruction with or without altered mental status due to a closed head or maxillofacial trauma

- Vascular injuries to great vessels of the thorax and neck with expanding hematoma

Staging

The Schafer-Fuhrman classification of laryngotracheal trauma is most commonly used[1]:

- Group 1: Minor endolaryngeal lacerations or hematomas; treatment is conservative with humidified oxygen, antibiotics and observation in intensive care unit (ICU) setting

- Group 2: Mucosal edema, hematoma without exposed cartilage, nondisplaced fracture; treatment is tracheostomy and panendoscopy

- Group 3: Massive edema, large mucosal lacerations, exposed cartilage, displaced fractures, vocal cord paralysis; treatment is tracheostomy followed by surgical exploration and repair

- Group 4: Similar to Group 3 but more severe disruption, unstable fracture or more than 2 fracture lines; treatment is emergent tracheostomy followed by surgical repair (and possible stent placement)

- Group 5: Complete laryngeal separation; treatment is emergent tracheostomy followed by surgical repair including stent placement

Prognosis

Prompt definitive care is associated with improved prognosis; delays may lead to scar tissue, strictures, infections, and other complications.[4]

Complications

- Aspiration

- Pneumothorax

- Airway obstruction due to hematoma or edema

- Chronic stenosis (long term) due to scar tissue and associated entities such as difficulties with phonation (generally more common following blunt trauma, especially when definitive treatment is delayed by 24 hours or more)

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury

- Pulmonary and wound infections

- Subcutaneous emphysema or pneumomediastinum (which may cause progressive obstruction of the airway lumen), air embolus

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

- Following surgery in cases requiring operative repair, the neck is fixed in flexion (Pearson position) for 1 to 2 weeks to take pressure off of the airway repair.

- Head of the bed elevation to decrease edema

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics prophylactically

- Ensure ETT balloon does not overlie repair as it will inhibit healing

Consultations

- Early otorhinolaryngology (ENT) involvement

- Interventional radiology (IR), gastroenterology (GI) to investigate potential concomitant injuries to vascular or digestive structures, respectively

Pearls and Other Issues

- Tracheal trauma may result from penetrating, inhalation or blunt mechanisms

- A salient iatrogenic cause of tracheal trauma is endotracheal damage from an overinflated ETT cuff

- The potential for tracheal trauma should be investigated early, as delays in diagnosis and treatment worsen prognosis

- Tracheal trauma may be associated with trauma to nearby structures including bony disruptions of the cervical spine, vascular injury or digestive tract involvement

- Securing and protecting the airway early is of paramount importance

- Potential complications include pneumothorax, aspiration, and infections, as well as delayed airway stenosis or vocal cord dysfunction from scar tissue formation

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Tracheal trauma represents a high-risk time-sensitive acute condition with the potential to adversely affect the patient's ability to maintain an airway. A team-based approach including emergency medicine, trauma and ENT specialists, as well as ancillary services including nursing and respiratory therapy, is required for optimal initial stabilization. Definitive treatment which often involves urgent surgical intervention, has been shown to be beneficial; delays in definitive treatment have been associated with poorer outcomes (Level V).