Introduction

Stable angina, also is known as typical angina or angina pectoris, is a symptom of myocardial ischemia. Stable angina is characterized by chest discomfort or anginal equivalent that is provoked with exertion and alleviated at rest or with nitroglycerin. This is often one of the first manifestations or warning signs of underlying coronary disease. Angina affects 10 million people in the United States (US); given this, it is important to not only recognize the signs and symptoms but also appropriately risk stratify and manage these individuals.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The mechanism behind stable angina is the result of supply-demand mismatch. The myocardial oxygen demand transiently exceeds the myocardial oxygen supply, which often leads to the manifestation of symptoms. There are several factors that contribute to stable angina; the most common etiology is coronary artery stenosis. This is further discussed below in the section titled ‘Pathophysiology.’[2]

Epidemiology

Coronary heart disease impacts over 17 million adults in the United States. Of the 17 million Americans affected, 55% of those are male. It contributes to over 500,000 deaths each year in the U.S. At age 40 years, the lifetime risk of developing coronary disease is estimated at 49% for men and 32% for women. The incidence of coronary events increases with age, although the male predominance with these events gradually narrows with advancing age.[3] Coronary heart disease/ischemic heart disease is not unique to the U.S., it is the leading cause of death in adults from low, middle, and high-income countries.[4]

Coronary heart disease can also cause significant debility. This debility can manifest in several ways, one of which is angina. Angina affects over 10 million people in the U.S., with over 500,000 new cases diagnosed each year.[1][3]

Pathophysiology

Simply put, the manifestation of angina is the result of an imbalance between the myocardial oxygen supply and the myocardial oxygen demand. It is important to understand the factors that contribute to each of these measures.

Endothelial cells line the coronary arteries; these cells are responsible for regulating vascular tone and preventing intravascular thrombosis. Any disruption in these two functions can lead to coronary heart disease. Multiple mechanisms can result in injury or impairment of the endothelial lining. These mechanisms include, but are not limited to, stress, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, viruses, bacteria, and immune complexes. Endothelial injury triggers an immune response, which ultimately leads to fibrous tissue formation. Smooth muscle remodeling/fibrous caps can lead to coronary artery stenosis or even acute coronary syndrome.

Coronary artery stenosis is the most common cause of myocardial ischemia. During times of increased myocardial oxygen demand, the stenosis prevents adequate myocardial oxygen supply. Four main factors contribute to oxygen demand: heart rate, systolic blood pressure, myocardial wall tension, and myocardial contractility. In states of increased demand such as illness, stress, and exercise – we rely on the body’s ability to up-regulate myocardial oxygen supply appropriately.

The four main factors that contribute to myocardial oxygen supply include coronary artery diameter and tone, collateral blood flow, perfusion pressure, and heart rate. While coronary artery stenosis is the most common, other conditions can lead to a decreased myocardial oxygen supply. These examples include, but are not limited, to coronary artery vasospasm, embolism, dissection, and micro-vascular disease.[2][5][6]

When the myocardial oxygen demand exceeds the myocardial oxygen supply, this will often manifest with symptoms. Myocardial ischemia stimulates chemosensitive and mechanoreceptive receptors within the cardiac muscle fibers and surrounding the coronary vessels. The activation of these receptors triggers impulses through the sympathetic afferent pathways from the heart to the cervical and thoracic spine. Each spinal level has a corresponding dermatome; the discomfort described by the patient will often follow the specific dermatomal pattern.[7][8]

It is important to conduct a thorough workup and evaluation to determine the cause of angina in each individual, understanding the etiology will allow for medical optimization and appropriate management of risk factors.

History and Physical

Individuals with stable angina will often have a subacute versus chronic presentation. It is important to use history and physical as a screening tool to identify high-risk individuals.

Routine screening of blood pressure, weight, sleep habits, stress, exercise tolerance, tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use should be incorporated.

As previously mentioned, typical angina usually presents as chest discomfort or anginal equivalent that is provoked with exertion and alleviated at rest or with nitroglycerin. Anginal equivalents vary, however, commonly can be described as shortness of breath, nausea, or fatigue that is out of proportion to the activity level.

It is important to distinguish between cardiac and non-cardiac chest discomfort. Discussing the details of the patient’s symptoms will further guide this differentiation. Relevant details include the quality, location, influencing factors, timing, and duration of the pain.[9]

Typical angina is often described as pressure-like, heaviness, tightness, or squeezing. Most commonly, it will affect a broad area of the chest rather than a specific spot. There may be radiation of the pain, depending on which dermatomes are affected.[10][11] Symptoms will be described as more severe with states of increased demand (i.e., walking, lifting, emotional stress, etc.) Symptoms generally last for two to five minutes, and relief is experienced when the provoking activity is stopped, or the patient takes nitroglycerin.[9]

The physical exam is most commonly unremarkable. You would not expect active ischemia in the setting of typical angina, leading to nonspecific physical exam findings.

Evaluation

Obtain an electrocardiogram to evaluate for active ischemia or evidence of previous infarction.

Obtain a chest x-ray to assist in ruling out noncardiac explanations for chest pain (i.e., infection, trauma, pneumothorax, etc.)

Obtain a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panel, and troponin. Lab work is important in risk stratification purposes and ruling out noncardiac explanations (i.e., anemia, infection, renal disease, etc.)

Use previous work up to risk stratify, consider stress testing versus further coronary evaluation in moderate to high-risk individuals.

Treatment / Management

Treatment for stable angina is geared toward reducing risk factors for presumed underlying coronary heart disease. An interdisciplinary approach would likely benefit individuals with multiple comorbidities; nutrition, diabetic educator, addiction counselor, physical and occupational therapy.

First-line Treatment Includes Lifestyle Modifications

- Tobacco cessation will result in the biggest risk reduction.

- Cigarette smoking is the leading avoidable cause of premature death. The risk of cardiovascular mortality in current smokers is roughly two times that of nonsmokers. Interestingly enough, the risk of cardiovascular mortality in former smokers is roughly equal to that of individuals who have never smoked. That said, it is imperative to continuously encourage smoking cessation regardless of age or duration of smoking history[12]

- Cholesterol reduction

- Evidence has supported that adherence to the Mediterranian diet (high in vegetables and fruits) reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease.[13]

- Blood pressure control

- The 2017 AHA/ACC guidelines define hypertension as systolic blood pressure ≥130 mmHg or diastolic pressure ≥80 mmHg.[14] Goal blood pressure will be unique to each patient; however, it is important to keep in mind that for each 20/10 mmHg increase in systolic/diastolic blood pressure, evidence has supported a two-fold increased risk of coronary heart and stroke-related mortality.[15]

- Diabetes mellitus management

- Recommend weight reduction, increased physical activity, and adequate control of comorbidities.[16]

- Weight loss

- Obesity is the second leading modifiable cause of premature deaths.[17] Weight-loss regimens should be catered to each patient, and the discussion should include lifestyle modifications and surgical options if appropriate.

- Aerobic exercise

- An average of 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week or 75 minutes of high-intensity exercise per week has been shown to decrease overall cardiac risk factors and, in turn, decrease the risk of coronary heart disease.[18]

(A1)

Pharmacologic

- Aspirin: Determine the risk of coronary heart disease in each patient. In low-risk individuals, the use of aspirin for primary prevention decreases the risk of nonfatal MI without benefit in all-cause mortality and nonfatal stroke.[19] Risk stratification is important as the use of aspirin comes with an increased risk of major bleeding.[20] Extracranial bleeding is the most common, however daily low-dose aspirin does increase the risk of intracranial hemorrhage as well.[21] As there is no evidence to support a mortality benefit for the use of aspirin in low-risk individuals, the risk of bleeding may outweigh the anticipated benefit. This should be decided on a case by case basis. High-risk individuals or individuals with known cardiovascular disease benefit from low dose daily aspirin. According to the meta-analysis performed by the Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration, daily aspirin significantly reduced the risk of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, and vascular death by 22%.[22]

- HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor: Statin therapy in high, moderate, and low-risk primary prevention subjects without clinical evidence of coronary disease has demonstrated a reduction in myocardial infarction, stroke, cardiovascular death, and total mortality.[23]

- ACE-inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB): May be used in primary prevention to assist in blood pressure control and recommended in the setting of high-risk individuals or known cardiovascular disease for cardioprotective efforts. The use of ACE-inhibitors or ARBs in high-risk individuals has been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.[24] (A1)

- Symptom Control

- Beta-blockers: Beta-blockers have been shown to decrease heart rate, blood pressure, and contractility, ultimately leading to decreased myocardial oxygen demand and decreasing anginal symptoms.[25]

- Nitrates: Nitrates relax vascular smooth muscle leading to dilation of veins primarily; this decreases cardiac preload and, in turn, decreases myocardial oxygen demand providing relief in anginal symptoms.[26]

- Ranolazine: The mechanism of action of this medication is not entirely understood; however, it is FDA approved for symptom control in stable angina.[27]

(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

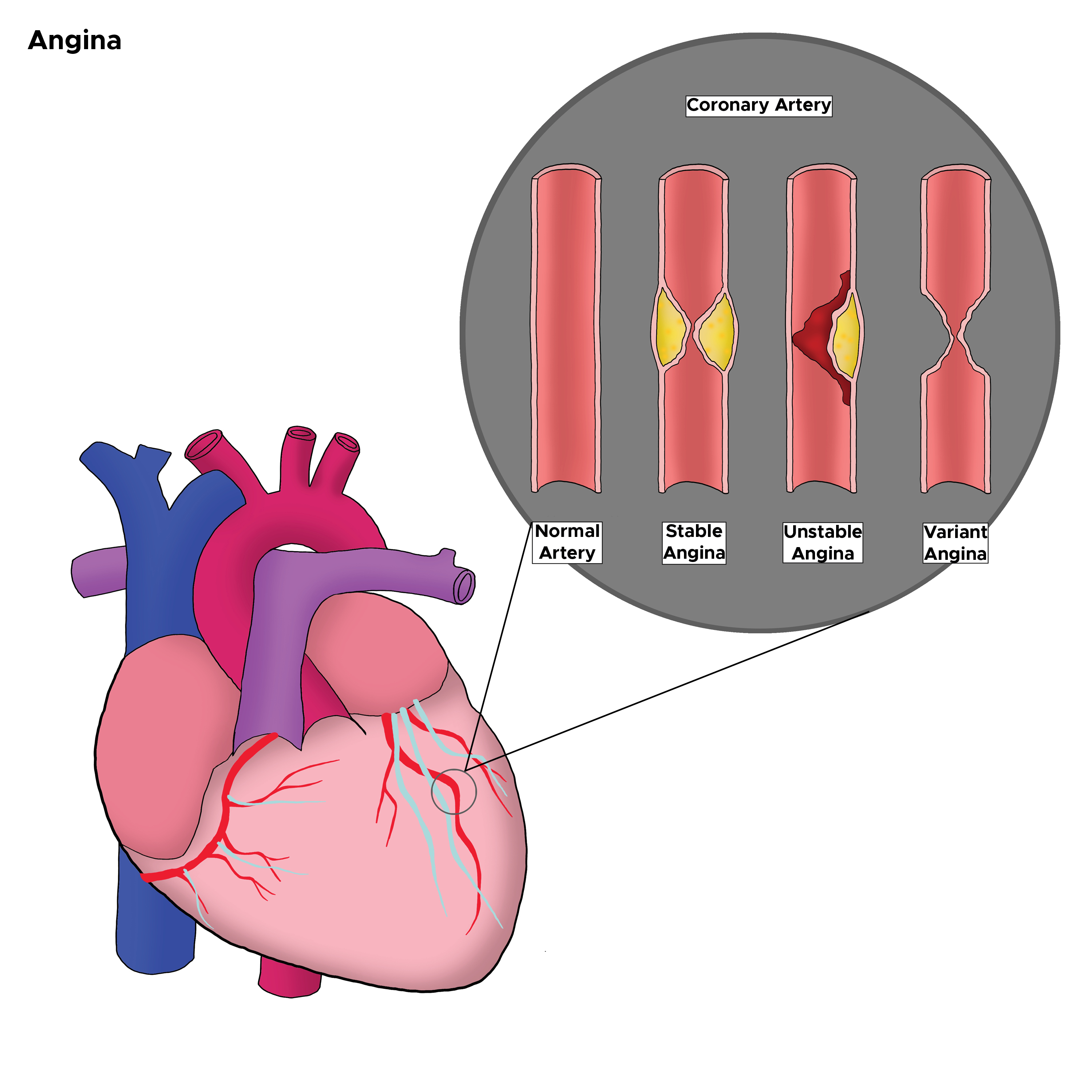

Listed below are several important differential diagnoses to consider (see Image. Types of Angina in the Coronary Artery). Brief details are listed next to each diagnosis to help differentiate from stable angina - for specific details and diagnostic criteria for each differential diagnosis, please reference their designated articles.

Cardiovascular

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Unstable angina: Detailed history is pertinent. Chest pain less likely to follow a predictable pattern, and the patient may even experience chest pain at rest.

- NSTEMI: Elevated cardiac enzymes with or without EKG changes.

- STEMI: Elevated cardiac enzymes with regional ST elevations noted on EKG.

- Myocarditis: Elevated cardiac enzymes with EKG changes.

- Pericarditis: Diffuse ST elevations noted on EKG with or without an elevation in cardiac enzymes. Chest pain is pleuritic and is often relieved with leaning forward.

Gastrointestinal

- Esophageal spasm: Temporal relationship to meals with or without dysphagia

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease: Temporal relationship to meals

Pulmonary

- Asthma: Abnormal lung sounds expected on the exam. Anticipate improvement in symptoms with pulmonary hygiene and inhaled beta-agonists.

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Abnormal lung sounds expected on the exam. Anticipate improvement in symptoms with pulmonary hygiene and inhaled beta-agonists.

- Pulmonary embolus: Chest pain pleuritic in nature. Typically, the presentation includes tachycardia and hypoxemia.

Musculoskeletal

- Costochondritis: Chest pain reproducible on the exam. History often reveals recent heavy lifting or exercise.

- Trauma: History reveals the mechanism of trauma. Imaging may reveal fractures.

Prognosis

Prognosis varies depending on the etiology of stable angina. In each case, regardless of etiology, aggressive risk factor modification is imperative. In individuals with stable angina, screening for increased frequency of symptoms or transition to unstable angina should be routinely performed.

Complications

The most important complication of stable angina is the possibility of progression to acute coronary syndrome. Risk factor modification and medical optimization should be utilized to decrease risk. These individuals require routine monitoring and attentive primary care providers.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Coronary heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, and efforts to educate the public regarding signs and symptoms of myocardial infarction, unstable angina, and stable angina should be continued. Efforts to educate the public regarding preventative measures such as risk factor modification and lifestyle modifications should also be a priority.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Typical angina affects over 10 million people in the United States. The presentation can vary from chest pressure to fatigue to shortness of breath to nausea. If this ultimately leads to myocardial infarction or unstable angina, the cardiology team is imperative in treatment; however, there are often many providers that will see this individual before that evolution. It is important to utilize an interprofessional team to best suit each patient. The primary care provider will play a large role in primary and secondary prevention, likely for many years prior to the development of symptoms. This provider may also recruit the help of a nutritionist, diabetic educator, addiction counselor, and physical and occupational therapy to help with modifying risk factors. The use of an interdisciplinary team is recommended to optimize patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kloner RA, Chaitman B. Angina and Its Management. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology and therapeutics. 2017 May:22(3):199-209. doi: 10.1177/1074248416679733. Epub 2016 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 28196437]

Ibáñez B, Heusch G, Ovize M, Van de Werf F. Evolving therapies for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015 Apr 14:65(14):1454-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.02.032. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25857912]

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O'Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2018 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018 Mar 20:137(12):e67-e492. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000558. Epub 2018 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 29386200]

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet (London, England). 2006 May 27:367(9524):1747-57 [PubMed PMID: 16731270]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGanz P, Abben RP, Barry WH. Dynamic variations in resistance of coronary arterial narrowings in angina pectoris at rest. The American journal of cardiology. 1987 Jan 1:59(1):66-70 [PubMed PMID: 3101476]

Hillis LD,Braunwald E, Coronary-artery spasm. The New England journal of medicine. 1978 Sep 28; [PubMed PMID: 210380]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceForeman RD. Mechanisms of cardiac pain. Annual review of physiology. 1999:61():143-67 [PubMed PMID: 10099685]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCrea F, Gaspardone A, Kaski JC, Davies G, Maseri A. Relation between stimulation site of cardiac afferent nerves by adenosine and distribution of cardiac pain: results of a study in patients with stable angina. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1992 Dec:20(7):1498-502 [PubMed PMID: 1452922]

Kreiner M, Okeson JP, Michelis V, Lujambio M, Isberg A. Craniofacial pain as the sole symptom of cardiac ischemia: a prospective multicenter study. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2007 Jan:138(1):74-9 [PubMed PMID: 17197405]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceConstant J. The clinical diagnosis of nonanginal chest pain: the differentiation of angina from nonanginal chest pain by history. Clinical cardiology. 1983 Jan:6(1):11-6 [PubMed PMID: 6831781]

Christie LG Jr, Conti CR. Systematic approach to evaluation of angina-like chest pain: pathophysiology and clinical testing with emphasis on objective documentation of myocardial ischemia. American heart journal. 1981 Nov:102(5):897-912 [PubMed PMID: 7304398]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLaCroix AZ, Lang J, Scherr P, Wallace RB, Cornoni-Huntley J, Berkman L, Curb JD, Evans D, Hennekens CH. Smoking and mortality among older men and women in three communities. The New England journal of medicine. 1991 Jun 6:324(23):1619-25 [PubMed PMID: 2030718]

Sotos-Prieto M, Bhupathiraju SN, Mattei J, Fung TT, Li Y, Pan A, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Hu FB. Changes in Diet Quality Scores and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Among US Men and Women. Circulation. 2015 Dec 8:132(23):2212-9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017158. Epub 2015 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 26644246]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWhelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC Jr, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA Sr, Williamson JD, Wright JT Jr. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979). 2018 Jun:71(6):e13-e115. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065. Epub 2017 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 29133356]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBlood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists' Collaboration, Ninomiya T, Perkovic V, Turnbull F, Neal B, Barzi F, Cass A, Baigent C, Chalmers J, Li N, Woodward M, MacMahon S. Blood pressure lowering and major cardiovascular events in people with and without chronic kidney disease: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2013 Oct 3:347():f5680. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5680. Epub 2013 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 24092942]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHennekens CH, Pfeffer MA, Newcomer JW, Jellinger PS, Garber A. Treatment of diabetes mellitus: the urgent need for multifactorial interventions. The American journal of managed care. 2014 May:20(5):357-9 [PubMed PMID: 25181565]

Hennekens CH, Andreotti F. Leading avoidable cause of premature deaths worldwide: case for obesity. The American journal of medicine. 2013 Feb:126(2):97-8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.06.018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23331433]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceManson JE, Hu FB, Rich-Edwards JW, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. A prospective study of walking as compared with vigorous exercise in the prevention of coronary heart disease in women. The New England journal of medicine. 1999 Aug 26:341(9):650-8 [PubMed PMID: 10460816]

Guirguis-Blake JM, Evans CV, Senger CA, O'Connor EA, Whitlock EP. Aspirin for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Events: A Systematic Evidence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of internal medicine. 2016 Jun 21:164(12):804-13. doi: 10.7326/M15-2113. Epub 2016 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 27064410]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAntithrombotic Trialists' (ATT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, Buring J, Hennekens C, Kearney P, Meade T, Patrono C, Roncaglioni MC, Zanchetti A. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet (London, England). 2009 May 30:373(9678):1849-60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19482214]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHuang WY,Saver JL,Wu YL,Lin CJ,Lee M,Ovbiagele B, Frequency of Intracranial Hemorrhage With Low-Dose Aspirin in Individuals Without Symptomatic Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA neurology. 2019 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 31081871]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAntithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2002 Jan 12:324(7329):71-86 [PubMed PMID: 11786451]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCollins R, Reith C, Emberson J, Armitage J, Baigent C, Blackwell L, Blumenthal R, Danesh J, Smith GD, DeMets D, Evans S, Law M, MacMahon S, Martin S, Neal B, Poulter N, Preiss D, Ridker P, Roberts I, Rodgers A, Sandercock P, Schulz K, Sever P, Simes J, Smeeth L, Wald N, Yusuf S, Peto R. Interpretation of the evidence for the efficacy and safety of statin therapy. Lancet (London, England). 2016 Nov 19:388(10059):2532-2561. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31357-5. Epub 2016 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 27616593]

Bangalore S, Fakheri R, Wandel S, Toklu B, Wandel J, Messerli FH. Renin angiotensin system inhibitors for patients with stable coronary artery disease without heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2017 Jan 19:356():j4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4. Epub 2017 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 28104622]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHauf-Zachariou U,Blackwood RA,Gunawardena KA,O'Donnell JG,Garnham S,Pfarr E, Carvedilol versus verapamil in chronic stable angina: a multicentre trial. European journal of clinical pharmacology. 1997; [PubMed PMID: 9174677]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAbrams J. Hemodynamic effects of nitroglycerin and long-acting nitrates. American heart journal. 1985 Jul:110(1 Pt 2):216-24 [PubMed PMID: 3925741]

Chaitman BR, Pepine CJ, Parker JO, Skopal J, Chumakova G, Kuch J, Wang W, Skettino SL, Wolff AA, Combination Assessment of Ranolazine In Stable Angina (CARISA) Investigators. Effects of ranolazine with atenolol, amlodipine, or diltiazem on exercise tolerance and angina frequency in patients with severe chronic angina: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004 Jan 21:291(3):309-16 [PubMed PMID: 14734593]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence