Introduction

Dysphonia is a widespread complaint affecting around one-third of the population worldwide during their life span.[1][2] Dysphonia is a general term to describe various changes in voice quality or production. This impairment of voice production diagnosed by a clinician is often used interchangeably with the complaint of hoarseness, a symptom of altered voice quality noticed by a patient.[3] While many patients experience dysphonia as a natural part of the aging process, it can be a symptom of a serious underlying condition. Clinicians must recognize that further evaluation is warranted when patients present with dysphonia for longer than four weeks or when it is associated with risk factors or other concerning signs and symptoms.[4][5][6]

Individuals with changes in voice production who fail to improve within four weeks should have a referral for further evaluation and visualization of the larynx. Sudden voice changes should always alarm clinicians as there could be an underlying sinister pathology. Evaluation should occur as early as possible whenever a severe pathology is suspected, irrespective of the timeframe.[5]

A wide range of laryngeal and extra-laryngeal conditions can lead to dysphonia, and there are many caveats associated with its evaluation. Early recognition of symptoms by the patient and provider, as well as visualization of the larynx, is crucial for early diagnosis. Various terminologies of the laryngeal lesions and insufficient laryngeal visualization make it difficult for providers to diagnose dysphonia. As a result, diagnosis and management are delayed due to misdiagnosis or lack of awareness. Management of dysphonia requires specialized knowledge and an interprofessional team approach.

Any individual of any age and sex can be affected by dysphonia; however, an increased prevalence is found in teachers, older adults, and other people with significant vocal demands.[7][8][9] Voice problems are experienced by 1 in 13 adults annually.[10]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The pathophysiology of dysphonia is characterized by irregularities in vocal fold oscillations related to muscle tone irregularity which may be due to hypertonicity, incomplete closure of the glottis during phonation, a change in vocal fold bulk, or a vocal fold lesion or tumor.[5][11] Vocal fold nodules are common and typically caused by voice misuse or overuse.[12]

The main risk factor for premalignant and malignant laryngeal cancer is smoking. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common vocal fold malignancy, comprising 85% to 95% of vocal fold cancers.[13][14] In laryngeal cancer, dysphonia is initially due to defective vibrations from the epithelial lesion, which may worsen as cancer progresses to involve the vocal ligament and thyroarytenoid muscle. The vocal fold can also become immobile or fixated, which is a sign of the involvement of the cricoarytenoid unit.[14]

Dysphonia is a symptom that can be attributed to many diseases. Some patients with head and neck tumors can present with dysphonia. It is crucial to recognize these, as evaluation delays can result in delayed diagnosis, higher staging, need for aggressive treatment, and poor outcomes.[15] Other conditions that may result in dysphonia include the following:

- Neurologic - vocal fold paralysis, spasmodic dysphonia, essential tremor, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Gastrointestinal - reflux esophagitis, eosinophilic esophagitis

- Rheumatologic/autoimmune - rheumatic arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Allergic

- Pulmonary - chronic pulmonary obstructive disease

- Musculoskeletal - muscle tension dysphonia, fibromyalgia, cervicalgia

- Psychological

- Traumatic - laryngeal fracture, iatrogenic injury, inhalational injury, blunt/penetrating trauma[16]

- Infectious - candidiasis

- Medication side effects - inhaled steroids, anticholinergics, antihistamines, decongestants, and antihypertensives[17]

The prevalence of dysphonia associated with these conditions varies. For instance, patients with spasmodic dysphonia or other laryngeal dystonia almost always manifest with dysphonia. On the contrary, not all patients with gastroesophageal reflux have dysphonia.

Epidemiology

Dysphonia has a lifetime prevalence of 29.9%. It can affect patients of all ages and genders, with an increased prevalence in patients who use their voice more often, such as singers, teachers, coaches, and telephone operators.[5][11] The incidence of vocal fold malignancy in the general population is 7 per 100,000.[14]

Analyses of cross-sectional data from the US in 2001 showed the point prevalence of dysphonia around 0.98% in a treatment-seeking population.[1] Consistent with previous studies, rates were higher among women (1.2% vs. 0.7% for men) and those over 70 (2.5% vs. 0.6%-1.8% for other age groups).[18][19] The true point prevalence of dysphonia-associated conditions is likely higher, as many patients with voice changes do not seek treatment, especially if dysphonia is transient and associated with an upper respiratory infection.[18]

History and Physical

The history obtained from patients with dysphonia should include a description of the voice problems. These include quality of the voice, fatigability, pitch range, loudness, phonatory effort, breathlessness or presence of conversational dyspnea, and impaired singing voice. Patient history should include past voice disorders and treatments, surgeries, medical history, current medications, environmental factors, and voice habits (hygiene). Understanding which component the patient finds most bothersome is critical.[20]

Associated signs and symptoms with dysphonia concerning for laryngeal malignancy may include weight loss, aspiration, and dysphagia. In later stages of laryngeal cancer, dyspnea and otalgia may be present. Other symptoms to ask about include cough and hemoptysis, which could indicate signs of malignancy. Questions about the history of reflux, such as heartburn, are also pertinent. Patients with dysphonia should receive screening for a history of smoking, alcohol use, neck radiation, and a family history of head and neck cancer.[14][21] Patients with an underlying neurological condition may present with dysphagia, tongue deviation or tremor, hand or extremity tremor, gait abnormalities, and cognitive delay.

Hoarseness may be the only abnormal physical exam finding. Voice assessment can be formal and informal while engaging the patient in conversation. At this time, the clinician can evaluate the components of voice, quality, pitch, nasality, loudness, prosody, and articulation. It is also important to note if any of the following are present: aphonia, tremor, glottic fry, diplophonia (two spontaneous pitches perceived simultaneously), and wet voice.

Assessment should include an auditory-perceptual evaluation of the voice; the two most common systems are the GRBAS and CAPE-V scales. The GRBAS scale is the gold standard in evaluating the perception of voice. It assesses the following components: grade (degree of voice dysfunction), roughness (irregularity), breathiness (air escape), asthenia (weakness), and strain (excessive effort). Each parameter receives a grade on a 4-point scale, with 0 being normal and 3 being severe.[20]

In addition to the perceptual voice assessment, a full head and neck examination should be performed at the initial encounter. Attention should be given to the patient’s respiratory pattern, noting any patterns of breath-holding or habitual use of residual air.

Evaluation

Several patient questionnaires help with the initial evaluation and ongoing management to assess for response to treatment. The Voice Handicap Index (VHI-10) provides insight into the functional and emotional aspects of the patient’s voice disturbance and is the most widely used patient survey.[22] Other surveys include the Voice Handicap Index (VHI), Voice-Related Quality of Life (VRQoL), and Glottal Function Index (GFI), which evaluates glottic insufficiency.[20][23]

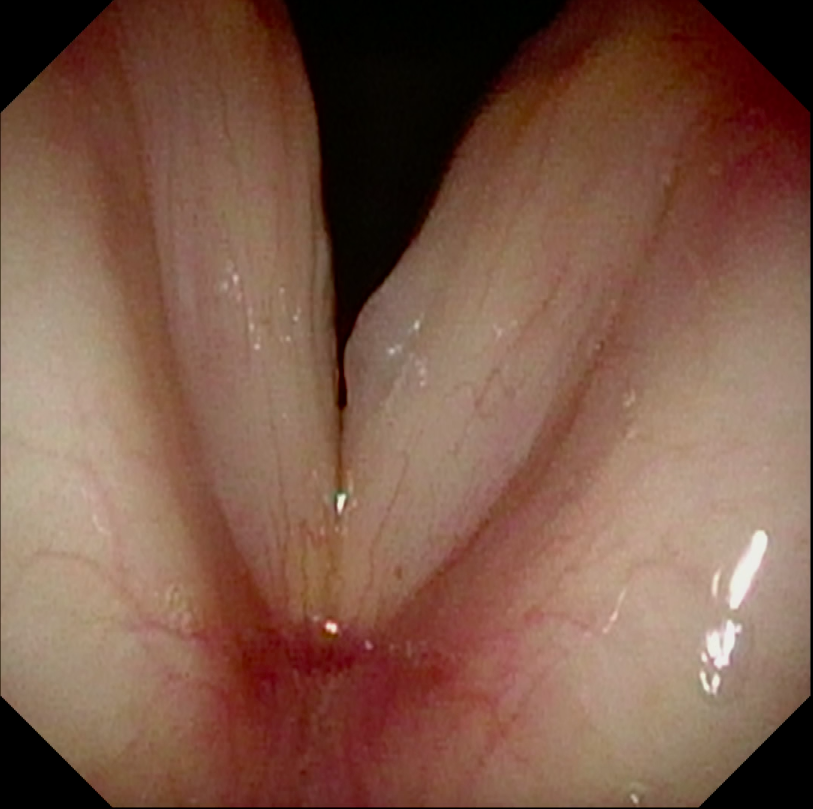

Patients with persistent dysphonia are referred to the otolaryngologist for an in-office laryngoscopy, which evaluates the laryngeal structure and function. The most commonly used instruments are mirrors, flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopes, or rigid endoscopes. During a flexible or rigid endoscopy, patient examinations can be quickly recorded and documented while the patient is vocalizing. These examinations provide valuable knowledge as the vocal folds can be directly visualized and may identify mucosal abnormalities that may not be seen on computed tomography scans or magnetic resonance imaging.[4] Radiographic imaging is not recommended as part of the routine evaluation, especially before an endoscopic evaluation.

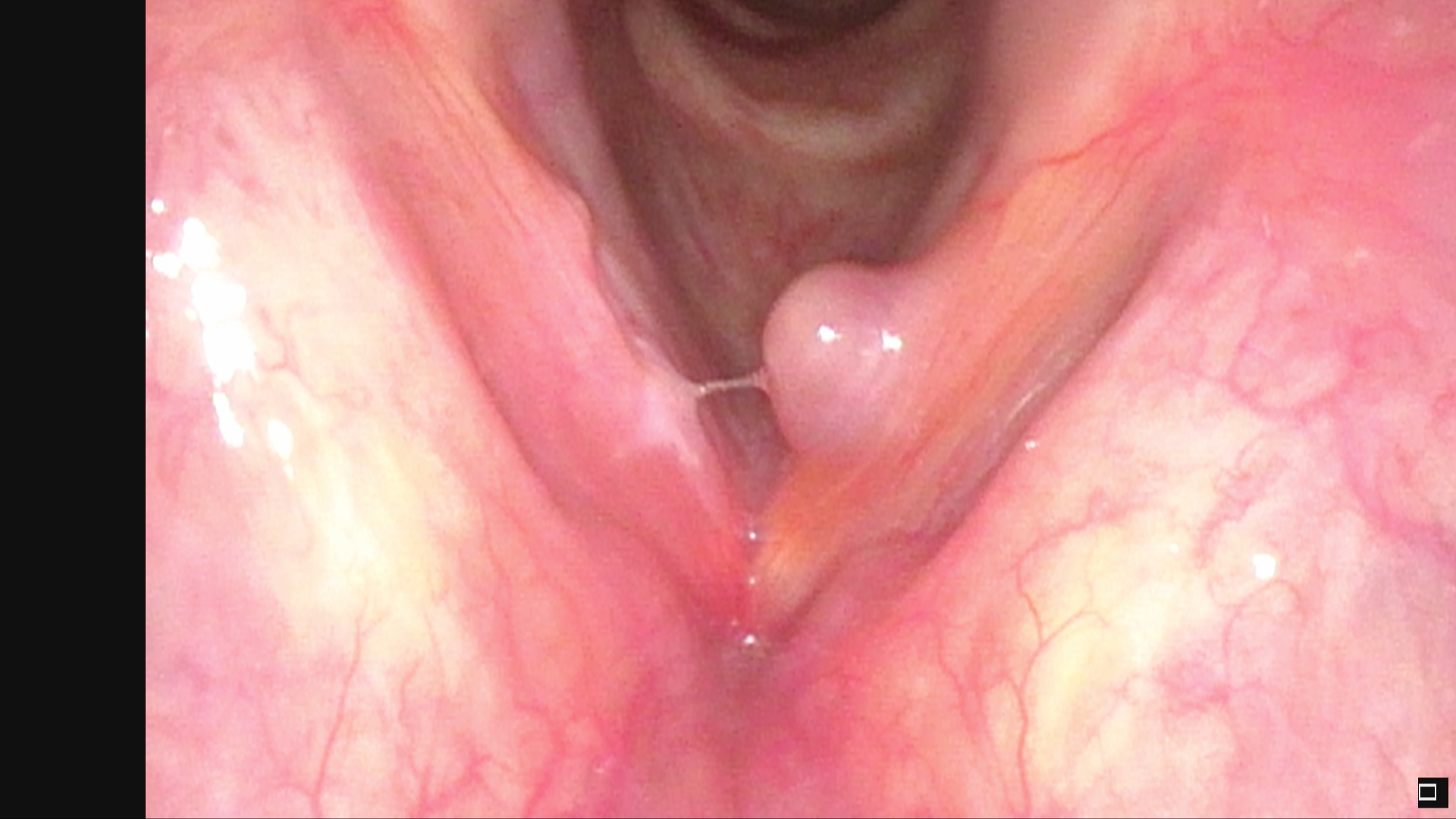

Laryngoscopy plays a crucial role in evaluating laryngeal patency in patients with laryngeal trauma, where visualization helps assess the need for surgical intervention (tracheotomy) and for follow-up cases where immediate surgery is not required.[24][25] Visualizing the larynx is also helpful in diagnosing fungal laryngitis from inhalers and must be distinguished from cancers by monitoring the response to antifungal medications or biopsy.[26] Unilateral vocal fold paralysis presents with breathy dysphonia and is routinely identified and followed with laryngoscopy.[27][28] Laryngoscopy is also helpful in patients with neuromuscular changes or cranial nerve deficits, as it helps identify neurologic causes of vocal dysfunction.[29] Benign vocal fold lesions, such as vocal fold cysts, nodules, and polyps, can be detected with laryngoscopy but are more easily identified and characterized with stroboscopy.

Videostroboscopy uses pulsed light synchronized with the patient’s vocal frequency to give the illusion of slow-motion mucosal oscillation of the vocal fold. This is the best diagnostic instrument for evaluating dysphonia to obtain information on mucosal pliability. The following components of the glottic cycle are obtained through stroboscopy: uniformity of glottic cycles (regularity), mucosal waveform, symmetry of the folds in both the lateral and vertical planes, and pattern of incomplete versus complete versus partial closure. Stroboscopy is helpful because it can detect abnormalities that may not be seen on a flexible or rigid endoscopy exam. Patients with malignant tumors may also benefit from surveillance via stroboscopy.

Treatment / Management

Treatment options for the underlying dysphonia diagnosis may include speech and language therapy, medical management, surgery, or a combination.[6] Clinical practice guidelines recommend against the initial treatment of dysphonia with medications such as proton-pump inhibitors, antibiotics, and steroids before evaluation by an otolaryngologist or laryngologist.[6][5][30](A1)

Generally, steroids and antibiotics should not be used to treat dysphonia with unclear etiology.

Speech and language therapy is typically the first-line treatment option for patients with dysphonia who do not otherwise meet indications for surgical intervention (eg, no suspicion of malignancy and vocal cord immobility identified on laryngoscopy or video stroboscopy examination). Speech therapy is often successful and the first line, even when patients present with benign vocal fold nodules.

Surgery is an option for patients with benign vocal fold lesions that do not respond to speech therapy. Meanwhile, patients who present with laryngeal dystonias may require interventions such as botulinum toxin injections, which have shown benefit in patients with disorders such as laryngeal dystonia/spasmodic dysphonia.[5] Patients with vocal fold granulomas may respond to steroid injections, which can be done in the office or the operating room. Patients with vocal fold immobility may require temporary measures such as injection of collagen-based products or calcium hydroxyapatite, which can also be performed in the office.[31] Alternatively, for permanent results, surgery can be performed to medialize the vocal fold with or without addressing the arytenoid, which not only addresses dysphonia but also prevents the risk of aspiration and subsequent development of pneumonia.[32] This procedure benefits post-stroke patients who may not recover from an injury or with iatrogenic recurrent laryngeal nerve injury from a thyroidectomy, spinal surgery, chest surgery, or an invasive lung tumor.(A1)

Patients diagnosed with laryngeal cancer may require chemotherapy, radiation, surgery, or a combination of these modalities, depending on the stage of their presentation.[21]

Differential Diagnosis

Consider the following list of differentials when managing a patient with dysphonia:

- Acute laryngitis (42.1%)[30]

- Chronic laryngitis (9.7%)

- Functional dysphonia

- Muscle tension dysphonia

- Benign lesions

- Vocal fold nodules

- Vocal fold cysts

- Malignant tumors

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Lymphoma

- Neurological conditions

- Multiple sclerosis

- Vocal tremor

- Laryngeal dystonia/Spasmodic dysphonia

- Parkinson disease[33]

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Myasthenia gravis

- Systemic conditions

- Hypothyroidism

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Systemic lupus

- Wegener granulomatosis

- Sarcoidosis

- Amyloidosis

- Tuberculosis

- Aging

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with dysphonia depends on the underlying condition. Patient prognosis can range from poor to excellent. Patients who have acute laryngitis only requiring symptomatic treatment will usually recover in 1 to 3 weeks. Meanwhile, patients with muscle tension dysphonia, vocal fold nodules/polyps, or other functional dysphonia may require voice rest or several speech therapy sessions to experience improvement in symptoms.

Patients with early-stage laryngeal cancer have reported 5-year survival rates of up to 95%, while those with late-stage laryngeal cancer have 5-year survival rates ranging from 30% to 63%, with the most frequent cause of death being Due to metastasis. The stark difference in prognosis between early and late-stage laryngeal cancer demonstrates the significance of early identification of laryngeal cancer.[14][21][13]

Complications

Dysphonia has generalized implications for various aspects of a patient's life, including psychological and physical. Treating multiple causes of dystonia, however, could also lead to several complications. Complications from injecting any material into the vocal fold are typically due to the inability to visualize the vocal folds fully. They include excessive secretions, paraglottic hemorrhage, bleeding, postoperative hematoma, and edema. Airway compromise and aspiration are rare complications of vocal fold injections, reported to be less than 5%.[31]

Complications of laryngeal surgery include postoperative hematoma, edema, infection, need for tracheostomy due to airway obstruction, implant migration or extrusion, failure to achieve adequate medialization, and need for revision surgery.[32]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Laryngeal cancer should be on the differential for patients with prolonged hoarseness or risk factors, which include: worsening dyspnea, aspiration, and weight loss. Clinicians should seek consultation with an otolaryngologist for further referral to exclude malignancy.

Patients presenting with persistent dysphonia that does not resolve after four weeks or worsens should seek attention from their medical provider. Voice rest and speech therapy is often the first-line treatment option for benign laryngeal lesions and muscle tension dysphonia.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Dysphonia is a common complaint affecting up to one-third of the adult population. All healthcare providers must recognize that dysphonia may be an underlying symptom of a condition that requires prompt medical attention and further evaluation. Failure to evaluate the larynx promptly can delay cancer diagnosis resulting in poorer patient outcomes. Dysphonia may be the first presenting symptom of an underlying neurological condition warranting further evaluation by a neurologist.[5]

Media

References

Cohen SM, Kim J, Roy N, Asche C, Courey M. Prevalence and causes of dysphonia in a large treatment-seeking population. The Laryngoscope. 2012 Feb:122(2):343-8. doi: 10.1002/lary.22426. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22271658]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCohen SM. Self-reported impact of dysphonia in a primary care population: an epidemiological study. The Laryngoscope. 2010 Oct:120(10):2022-32. doi: 10.1002/lary.21058. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20830762]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJohns MM 3rd, Sataloff RT, Merati AL, Rosen CA. Shortfalls of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery's Clinical practice guideline: Hoarseness (Dysphonia). Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2010 Aug:143(2):175-7; discussion 175-80. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.05.026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20647114]

Reghunathan S, Bryson PC. Components of Voice Evaluation. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2019 Aug:52(4):589-595. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2019.03.002. Epub 2019 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 31072640]

Stachler RJ, Francis DO, Schwartz SR, Damask CC, Digoy GP, Krouse HJ, McCoy SJ, Ouellette DR, Patel RR, Reavis CCW, Smith LJ, Smith M, Strode SW, Woo P, Nnacheta LC. Clinical Practice Guideline: Hoarseness (Dysphonia) (Update). Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2018 Mar:158(1_suppl):S1-S42. doi: 10.1177/0194599817751030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29494321]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFrancis DO, Smith LJ. Hoarseness Guidelines Redux: Toward Improved Treatment of Patients with Dysphonia. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2019 Aug:52(4):597-605. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2019.03.003. Epub 2019 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 31101359]

Jones K, Sigmon J, Hock L, Nelson E, Sullivan M, Ogren F. Prevalence and risk factors for voice problems among telemarketers. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2002 May:128(5):571-7 [PubMed PMID: 12003590]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLong J, Williford HN, Olson MS, Wolfe V. Voice problems and risk factors among aerobics instructors. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 1998 Jun:12(2):197-207 [PubMed PMID: 9649075]

Davids T, Klein AM, Johns MM 3rd. Current dysphonia trends in patients over the age of 65: is vocal atrophy becoming more prevalent? The Laryngoscope. 2012 Feb:122(2):332-5. doi: 10.1002/lary.22397. Epub 2012 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 22252988]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBhattacharyya N. The prevalence of voice problems among adults in the United States. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Oct:124(10):2359-62. doi: 10.1002/lary.24740. Epub 2014 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 24782443]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVan Houtte E, Van Lierde K, Claeys S. Pathophysiology and treatment of muscle tension dysphonia: a review of the current knowledge. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2011 Mar:25(2):202-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2009.10.009. Epub 2010 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 20400263]

Kraimer KL, Husain I. Updated Medical and Surgical Treatment for Common Benign Laryngeal Lesions. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2019 Aug:52(4):745-757. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2019.03.017. Epub 2019 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 31078305]

Badwal JS. Total Laryngectomy for Treatment of T4 Laryngeal Cancer: Trends and Survival Outcomes. Polski przeglad chirurgiczny. 2018 Aug 6:91(3):30-37. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0012.2307. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31243165]

Schultz P. Vocal fold cancer. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2011 Dec:128(6):301-8. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2011.04.004. Epub 2011 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 21959270]

Chen AY, Schrag NM, Halpern M, Stewart A, Ward EM. Health insurance and stage at diagnosis of laryngeal cancer: does insurance type predict stage at diagnosis? Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2007 Aug:133(8):784-90 [PubMed PMID: 17709617]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBiswas S, Saran M. Blunt Trauma to the Neck Presenting as Dysphonia and Dysphagia in a Healthy Young Woman; A Rare Case of Traumatic Laryngocele. Bulletin of emergency and trauma. 2020 Apr:8(2):129-131. doi: 10.30476/BEAT.2020.46455. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32420400]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHaft S, Farquhar D, Carey R, Mirza N. Anticholinergic Use Is a Major Risk Factor for Dysphonia. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2015 Oct:124(10):797-802. doi: 10.1177/0003489415585867. Epub 2015 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 25944595]

Roy N, Merrill RM, Gray SD, Smith EM. Voice disorders in the general population: prevalence, risk factors, and occupational impact. The Laryngoscope. 2005 Nov:115(11):1988-95 [PubMed PMID: 16319611]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRoy N, Kim J, Courey M, Cohen SM. Voice disorders in the elderly: A national database study. The Laryngoscope. 2016 Feb:126(2):421-8. doi: 10.1002/lary.25511. Epub 2015 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 26280350]

Hogikyan ND, Sethuraman G. Validation of an instrument to measure voice-related quality of life (V-RQOL). Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 1999 Dec:13(4):557-69 [PubMed PMID: 10622521]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSteuer CE, El-Deiry M, Parks JR, Higgins KA, Saba NF. An update on larynx cancer. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2017 Jan:67(1):31-50. doi: 10.3322/caac.21386. Epub 2016 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 27898173]

Rosen CA, Lee AS, Osborne J, Zullo T, Murry T. Development and validation of the voice handicap index-10. The Laryngoscope. 2004 Sep:114(9):1549-56 [PubMed PMID: 15475780]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBach KK, Belafsky PC, Wasylik K, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the glottal function index. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2005 Nov:131(11):961-4 [PubMed PMID: 16301366]

Mace SE. Blunt laryngotracheal trauma. Annals of emergency medicine. 1986 Jul:15(7):836-42 [PubMed PMID: 3729109]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchaefer SD. The acute management of external laryngeal trauma. A 27-year experience. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1992 Jun:118(6):598-604 [PubMed PMID: 1637537]

Ishizuka T, Hisada T, Aoki H, Yanagitani N, Kaira K, Utsugi M, Shimizu Y, Sunaga N, Dobashi K, Mori M. Gender and age risks for hoarseness and dysphonia with use of a dry powder fluticasone propionate inhaler in asthma. Allergy and asthma proceedings. 2007 Sep-Oct:28(5):550-6 [PubMed PMID: 18034974]

Rosenthal LH, Benninger MS, Deeb RH. Vocal fold immobility: a longitudinal analysis of etiology over 20 years. The Laryngoscope. 2007 Oct:117(10):1864-70 [PubMed PMID: 17713451]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHartl DA, Hans S, Vaissière J, Brasnu DA. Objective acoustic and aerodynamic measures of breathiness in paralytic dysphonia. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2003 Apr:260(4):175-82 [PubMed PMID: 12709799]

Mao VH, Abaza M, Spiegel JR, Mandel S, Hawkshaw M, Heuer RJ, Sataloff RT. Laryngeal myasthenia gravis: report of 40 cases. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2001 Mar:15(1):122-30 [PubMed PMID: 12269627]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceReiter R, Hoffmann TK, Pickhard A, Brosch S. Hoarseness-causes and treatments. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2015 May 8:112(19):329-37. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0329. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26043420]

Mallur PS, Rosen CA. Office-based laryngeal injections. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2013 Feb:46(1):85-100. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2012.08.020. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23177408]

Zimmermann TM, Orbelo DM, Pittelko RL, Youssef SJ, Lohse CM, Ekbom DC. Voice outcomes following medialization laryngoplasty with and without arytenoid adduction. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Aug:129(8):1876-1881. doi: 10.1002/lary.27684. Epub 2018 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 30582612]

Sewall GK, Jiang J, Ford CN. Clinical evaluation of Parkinson's-related dysphonia. The Laryngoscope. 2006 Oct:116(10):1740-4 [PubMed PMID: 17003722]