Nuclear Medicine PET Scan Cardiovascular Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation

Nuclear Medicine PET Scan Cardiovascular Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation

Introduction

Noninvasive imaging plays a pivotal role in assessing epicardial coronary artery anatomy, myocardial perfusion, and ventricular function in patients with known or suspected cardiovascular diseases. The increasing global burden of cardiovascular diseases has led to the introduction of highly sensitive and specific imaging modalities.[1][2] Over the last two decades, the development of new software has contributed tremendously and broadened non-invasive imaging dimensions. Molecular imaging has revolutionized diagnostic imaging by utilizing high spatial and temporal resolution, significantly improving sensitivity and specificity.[3] Because of increasing knowledge of cardiovascular biology and advances in imaging technologies, molecular imaging has become an essential tool in the fields of cardiovascular medicine.[4]

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a prime example of molecular imaging, which has contributed immensely to understanding cardiac anatomy and pathophysiology over the last two decades.[5][6] Similar to other molecular imaging, PET utilizes intrinsic tissue characteristics as the source of image contrast, which leads to a better understanding of integrative biology and provides earlier detection and accurate diagnosis of disease.[7] Stress myocardial positron emission tomography with Rubidium (Rb) provides a powerful estimate of cardiovascular mortality and accurately predicts prognosis in patients with coronary artery disease.[8] Whereas PET with 2-deoxy-2-(F) fluoro-D-glucose (F-FDG) has been utilized as the gold standard for assessing myocardial viability with the help of glucose metabolism.[9]

The introduction of hybrid positron emission tomography with computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging by utilizing 3-dimensional acquisitions has been demonstrated as an important milestone in the field of myocardial perfusion imaging. It has significantly shortened the imaging protocol and reduced radiation exposure.[10] Cardiac PET has also been proven as an effective non-invasive imaging modality for diagnosing myocardial infiltrative diseases, cardiac ischemia, and cardiac infections.[11][12][13]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The human myocardium utilizes fatty acids as a primary substrate for its metabolism and production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Glucose and ketone bodies are the secondary sources of ATP production for cardiac myocytes.[14] Although a central mechanism regulates the relative use of these resources, the conditions of stress, disease, metabolic insults, and availability can alter the relative utilization of these resources. It is reported that in patients with diabetes mellitus, the proportion of ATP produced from fatty acids increases.[15] On the other hand, in obstructive coronary artery disease and heart failure, metabolism shifts towards glucose as it requires less oxygen compared to fatty acid metabolism.[16] Cardiac positron emission tomography utilizes this relative substrate to assess pathology and the underlying mechanisms for disease.[17]

Indications

Indications of cardiac PET may include:[18][19]

- Assessment of hibernating myocardium in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction prior to revascularisation procedure.

- Assessment of myocardial viability in patients with a fixed defect on single-photon emission cardiac tomography (SPECT), who might benefit from revascularization.

- Assessment of patients prior to referral for cardiac transplantation.

- Diagnosis and assessment of the physiologic significance of coronary artery disease

- Assessment of coronary artery disease in symptomatic patients where other non-invasive investigations remain equivocal

- Differentiating ischemic and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.

- Differentiating underlying mechanisms and causes of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy.

- Differentiation of benign cardiac lesions from malignant lesions

- Identification of an unknown primary tumor when patients present with metastatic disease or paraneoplastic syndrome.

- Adjunct tool in detecting infiltrative diseases such as cardiac sarcoidosis

- Monitoring the cardiac effect of chemotherapy on known malignancies.

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications of Cardiac PET, and relative contraindications may include;

- Pregnancy

- Morbid obesity, when the patient dimensions are beyond the scanning chamber capability

- Claustrophobia

- The patient does not sign the informed consent

Equipment

The following equipment is required:

- Nuclear laboratory

- Scanning machine with a gamma camera

- Large-bore intravenous cannula, for injection of a radioisotope

- Computer with installed software and image display

- Standard radiation protection equipment

Personnel

- Nuclear laboratory technologist

- A registered nurse for cannulation and drug administration

- A physician with training in interpretation nuclear imaging

Preparation

The goal of preparation is to suppress glucose uptake in the myocardium and shift the cardiac metabolism to fatty acids.

- The patient is advised to avoid strenuous exercise 24 hours before going for a test.[20]

- The patient is advised to utilize a high-fat and low-carbohydrate diet 24-48 hours before undergoing a PET scan in order to enhance the sensitivity of the test.[11]

- Fasting could be an option as an alternative to a high-fat diet for enhancing myocardial fat metabolism.[21]

Technique or Treatment

Basic Principle

Radiotracer used in positron emission tomography undergoes radioactive decay, which releases a positron. A positron is an antiparticle of an electron. It travels a short distance (depending on the positron range) and interacts with an electron. This interaction between the electron and positron results in the destruction of both the particles and conversion into two photons of the same energy but in the opposite direction. PET depends on the detection of these photons simultaneously on the opposite side detectors. By this coincident detection of two photons per decay, PET provides greater spatial resolution and less noise than single-photon emission tomography (SPECT).[22]

A three-dimensional image of myocardial perfusion is generated by mapping the distribution of the radiotracer both at stress and rest. The absolute concentration of radiotracer can also be mapped dynamically as it distributes in the myocardium. After that, the high-quality three-dimensional perfusion images are collected over the period of 2–10 min. In hybrid PET/CT imaging, a PET scan is combined with a fast CT scan, which delineates anatomical structures around the heart. The hybrid CT scan can be used to correct attenuation artifacts and scattering of PET data, which allows an accurate measurement of myocardial perfusion.[23]

Radiotracers

Perfusion Tracers: Although there are multiple radiotracers available worldwide, rubidium-82 (Rb) and nitrogen-13-ammonia (N-ammonia) are most commonly used in clinical practice.

Rb is a potassium analog that is produced artificially in the nuclear laboratory via a generator. It has a short half-life of around 76 seconds, and it mimics Thallium-201 in its kinetic properties. Rb is the most commonly used radiotracer for the assessment of myocardial perfusion with PET.[24]

A cyclotron produces N-ammonia. It has a half-life of around 10 min. After injection, N-ammonia is converted to glutamine, and it disappears rapidly from the circulation. Its uptake in the lungs increases significantly in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and chronic lung diseases, which may affect the images' quality adversely by increasing background activity. This effect can be minimized by increasing the time between injection and image acquisition to optimize the contrast between myocardial and background activity. Although N-ammonia allows very high-resolution imaging, its use is limited due to its production by an on-site cyclotron.[25]

Although oxygen-15-water (O-water) radiotracer diffuses freely across the membrane and its retention in the cell is not affected by the metabolic factors, it produces noisy and low count images, so its use is not recommended for clinical imaging.[26]

Fluorine-18-flurpiridaz (F-flurpiridaz) is another radiotracer with relatively smaller kinetic positron energy, leading to a short positron range. F-flurpiridaz has a very long half-life of 110 min as compared to other radiotracers. It does not require cyclotron on-site, which makes it a favorable radiotracer for clinical use. Recent trial shows an added advantage of myocardial blood flow measurement with F-flurpiridaz cardiac PET, making it an excellent agent for coronary artery disease diagnosis.[27]

Viability Tracers: 18F-FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose) is a glucose analog globally used to assess myocardial viability. FDA also approves it for metabolic scanning in clinical oncology. It utilizes myocardial glucose use as an indicator of myocardial viability. Its increased uptake could be found in ischemic tissue, whereas reduced or absent uptake signifies a myocardial scar.[28]

Protocol

A positron emission tomography (PET) imaging usually takes less time than single-photon emission tomography (SPECT) due to the shorter half-life of radiotracers used in PET. Complete stress–rest myocardial perfusion study with Rb and can be completed within 30 min.

In a typical Rb protocol, a tomographic acquisition used for the patient positioning is followed by a CT transmission scan. Then the radiotracer is injected into the patient at rest. After injecting a radiotracer, six minutes rest imaging acquisition is initiated. After completion of rest imaging, a second CT transmission scan is performed, followed by pharmacologic stress. Pharmacologic stress is commonly produced by using dipyridamole, adenosine, or regadenoson infusion. At two minutes after the infusion of pharmacologic stressor, Rb is administered using a separate intravenous line. A 6-min stress imaging acquisition protocol is initiated with the start of the Rb infusion. Both the rest and stress CT transmission scans are acquired by holding the breath at the end of expiration, and patients are advised to breathe normally during the PET image acquisition.[29]

The O-water tracer has a short decay time similar to Rb. A similar protocol is followed with 10–30 mCi of the radiotracer is infused to measure the activity for both the stress and a rest image. The activity is measured for around 5–6 minutes.[30]

PET imaging with N-ammonia protocol usually requires a longer time due to the longer decay life. Immediately after the acquisition of a tomogram for patient positioning, a CT transmission scan is acquired. Then N-ammonia is injected into the patients at rest after starting a 10-min rest imaging acquisition protocol. After completion of the rest images, a stress CT transmission scan is usually acquired. Similar to the Rb PET protocol, pharmacologic stress is produced by dipyridamole, adenosine, or regadenoson. Three minutes later, N-ammonia is administered using a separate intravenous. Just like rest imaging, stress image acquisition starts a few seconds before the stress N-ammonia injection.[31]

Currently, available PET scanners operate in three-dimension detection mode without an interplane septum. This mode enables the scanners to detect all coincident photon pairs. The three-dimension model provides an advantage of up to six times higher photon sensitivity than the traditional two-dimensional model. The quantitative three-dimensional PET imaging still has substantial technical limitations due to scanner saturation with the radiotracers' standard bolus dose. Therefore, quantitative PET imaging may require a slow infusion of radiotracers to avoid scanner saturation during first-pass arterial activity.[32]

Attenuation Correction

Respiratory and cardiac motions are the major source of attenuation artifacts in PET scans. Easy availability of attenuation correction is a key component of PET scan, which is routinely not available in SPECT. It is usually performed with transmission sources on standalone PET scanners. Whereas in hybrid PET/CT, the attenuation correction map is formed with the help of non-contrast CT imaging, which is acquired separately for both the rest and stress studies to ensure perfect alignment with PET scan.[33] All new PET scanner models are available in the hybrid PET/CT configuration. Significant differences have been reported between traditional transmission CT-based and CT-based attenuation correction. Although the problem related to the attenuation artifacts has not yet been fully resolved, careful visual verification of alignment is required to minimize these artifacts. New methods, including automatic registration of CT and PET maps, are also proposed to reduce the attenuation artifacts.[34]

Cardiac PET and hybrid PET/ CT provides a highly accurate assessment of obstructive CAD. Overall, the average sensitivity for detecting at least one coronary artery was reported as 89% (range: 83–100%), whereas the average specificity was reported as high as 90% (range: 73% to 100%).[35] Kaster and colleagues achieved up to 100% sensitivity for detecting obstructive CAD while considering transient ischemic dilation. Every radiotracer has unique characteristics, so it is essential to have isotope-specific normal limits for PET perfusion analysis.[36]

Interpretation

Myocardial perfusion imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) is performed with the flow tracers, including Rubidium 82 and Nitrogen 13 ammonia. Images are taken at rest as well as during pharmacologic or physiologic stress. Metabolism imaging using positron emission tomography identifies metabolic activity in the myocardium. It is performed with fluorine 18 2-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG) as a metabolic radiotracer.

Perfusion and metabolic images taken by PET scan are displayed on a computer monitor by using linear grayscale, monochromatic color scale, or a multicolor scale, depending on the available display type or operator preference. Images are displayed in the following orientations:[37]

- Short-axis views are displayed by slicing the heart perpendicular to the left ventricle's long axis from apex to base.

- Vertical long-axis views are prepared by slicing the heart vertically from the septum to the lateral wall.

- Horizontal long-axis views are made by slicing the heart from the inferior to the anterior wall.

The above-mentioned views and slices are then aligned and displayed adjacent to each other to compare and interpret metabolic and perfusion images.

Following alignment, the perfusion images are first normalized with the metabolism images using the maximal myocardial pixel value in each of the aforementioned three image sets. The perfusion images are then normalized to their own maximum pixel value. The metabolism images are usually normalized to the maximum counts in the same myocardial region on the perfusion image.[38]

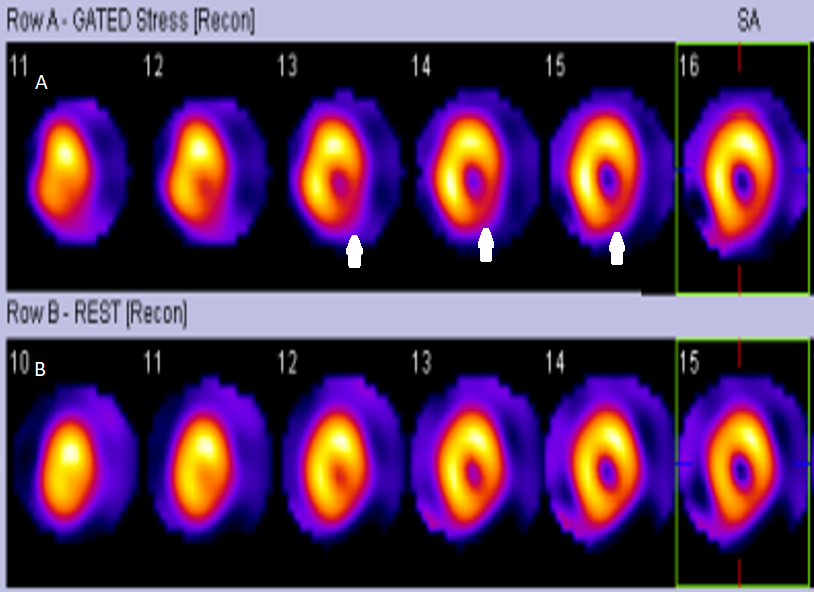

Perfusion images at rest and stress are compared. Normal myocardial perfusion signifies the absence of obstructive epicardial coronary artery disease. In contrast, stress-induced regional myocardial perfusion abnormalities (normalize at rest) imply ischemia due to obstructive epicardial or small vessel disease. (Figure 1)

On the other hand, impaired perfusion both at stress and rest suggests a myocardial scar. The size and extent of perfusion defect and reversibility are quantified using the 17-segment model of the left ventricle.[39]

In addition to this, cardiac chamber size, transient ischemia-induced cavity dilatation, right ventricular uptake, and pulmonary tracer uptake are also identified, and these findings signify different pathologies and diseases.

For interpretation of metabolism images, the extent and location of regional myocardial FDG uptake are compared and described according to the qualitative description of perfusion defect severity and extent. Regional increases in FDG uptake relative to myocardial blood flow is called perfusion-metabolism mismatch, and it a characteristic feature of hibernating myocardium.(Figure 2) While reductions in FDG uptake in proportion to the decreased myocardial perfusion are called the perfusion-metabolism match, they are characteristic features of myocardial scar.[39]

Complications

A cardiac PET scan is a pretty safe procedure in the contemporary era. Radiation exposure and radiation-related adverse reaction is the only considerable complication of PET scan. Although the initial three-dimensional PET/CT technology was associated with significant radiation exposure, the advances in image acquisition and new software methods offer dose reduction in cardiac PET imaging. The newer PET software allows the reconstruction of both the relative myocardial perfusion and absolute myocardial blood flow data from the same scan. Due to the increased sensitivity of PET, it is now possible to obtain high-quality perfusion images at doses as low as 20 mCi.[32]

Clinical Significance

Unique metabolic patterns are associated with the mechanism and pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases. Metabolic imaging in the form of positron emission tomography (PET) could be utilized to identify these patterns, which will guide towards early and accurate diagnosis and appropriate decision making.[40] Cardiac positron emission tomography can be used as an effective tool to assess new therapeutic strategies, which will ultimately help patients suffering from cardiovascular diseases.[41]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cardiovascular diseases are the major cause of death worldwide. Early and accurate diagnosis of cardiac diseases guides the therapeutic interventions, which would lead to a reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Cardiac positron emission tomography is a powerful, noninvasive imaging technology that is increasingly penetrating clinical cardiovascular imaging. The advantages of PET scan include clinical assessment of myocardial perfusion, quantification of myocardial blood flow, and assessment of viability with high accuracy. Despite high single-test costs, PET has been proven to be cost-effective due to its high accuracy leading to early diagnosis and treatment of disease. It has also made its place as an adjunct advanced cardiac imaging tool in the diagnosis of infiltrative cardiac diseases such as cardiac sarcoidosis. The advent of hybrid imaging with a combination of PET and CT-derived morphologic parameters has further improved the diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity.[42] Comprehensive knowledge of the imaging modalities is mandatory, especially for healthcare physicians, for the selection of an appropriate diagnostic test.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Shaw LJ, Marwick TH, Zoghbi WA, Hundley WG, Kramer CM, Achenbach S, Dilsizian V, Kern MJ, Chandrashekhar Y, Narula J. Why all the focus on cardiac imaging? JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2010 Jul:3(7):789-94. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.05.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20633864]

Bhattacharyya S, Lloyd G. Improving Appropriateness and Quality in Cardiovascular Imaging: A Review of the Evidence. Circulation. Cardiovascular imaging. 2015 Dec:8(12):. pii: e003988. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.115.003988. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26628582]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMankoff DA. A definition of molecular imaging. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2007 Jun:48(6):18N, 21N [PubMed PMID: 17536102]

Lindner JR, Sinusas A. Molecular imaging in cardiovascular disease: Which methods, which diseases? Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. 2013 Dec:20(6):990-1001. doi: 10.1007/s12350-013-9785-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24092271]

Ohira H, Mc Ardle B, Cocker MS, deKemp RA, Dasilva JN, Beanlands RS. Current and future clinical applications of cardiac positron emission tomography. Circulation journal : official journal of the Japanese Circulation Society. 2013:77(4):836-48 [PubMed PMID: 23486164]

Krumm P, Mangold S, Gatidis S, Nikolaou K, Nensa F, Bamberg F, la Fougère C. Clinical use of cardiac PET/MRI: current state-of-the-art and potential future applications. Japanese journal of radiology. 2018 May:36(5):313-323. doi: 10.1007/s11604-018-0727-2. Epub 2018 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 29524169]

Massoud TF, Gambhir SS. Molecular imaging in living subjects: seeing fundamental biological processes in a new light. Genes & development. 2003 Mar 1:17(5):545-80 [PubMed PMID: 12629038]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDorbala S, Di Carli MF, Beanlands RS, Merhige ME, Williams BA, Veledar E, Chow BJ, Min JK, Pencina MJ, Berman DS, Shaw LJ. Prognostic value of stress myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography: results from a multicenter observational registry. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013 Jan 15:61(2):176-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.043. Epub 2012 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 23219297]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKobylecka M, Mączewska J, Fronczewska-Wieniawska K, Mazurek T, Płazińska MT, Królicki L. Myocardial viability assessment in 18FDG PET/CT study (18FDG PET myocardial viability assessment). Nuclear medicine review. Central & Eastern Europe. 2012 Apr 24:15(1):52-60. doi: 10.5603/nmr-18731. Epub 2012 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 23047574]

Li Z, Gupte AA, Zhang A, Hamilton DJ. Pet Imaging and its Application in Cardiovascular Diseases. Methodist DeBakey cardiovascular journal. 2017 Jan-Mar:13(1):29-33. doi: 10.14797/mdcj-13-1-29. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28413580]

Blankstein R, Osborne M, Naya M, Waller A, Kim CK, Murthy VL, Kazemian P, Kwong RY, Tokuda M, Skali H, Padera R, Hainer J, Stevenson WG, Dorbala S, Di Carli MF. Cardiac positron emission tomography enhances prognostic assessments of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Feb 4:63(4):329-36. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.022. Epub 2013 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 24140661]

Tamaki N, Kawamoto M, Tadamura E, Magata Y, Yonekura Y, Nohara R, Sasayama S, Nishimura K, Ban T, Konishi J. Prediction of reversible ischemia after revascularization. Perfusion and metabolic studies with positron emission tomography. Circulation. 1995 Mar 15:91(6):1697-705 [PubMed PMID: 7882476]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSaby L, Laas O, Habib G, Cammilleri S, Mancini J, Tessonnier L, Casalta JP, Gouriet F, Riberi A, Avierinos JF, Collart F, Mundler O, Raoult D, Thuny F. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography for diagnosis of prosthetic valve endocarditis: increased valvular 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake as a novel major criterion. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013 Jun 11:61(23):2374-82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.092. Epub 2013 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 23583251]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJaswal JS, Keung W, Wang W, Ussher JR, Lopaschuk GD. Targeting fatty acid and carbohydrate oxidation--a novel therapeutic intervention in the ischemic and failing heart. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011 Jul:1813(7):1333-50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.015. Epub 2011 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 21256164]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmaral N, Okonko DO. Metabolic abnormalities of the heart in type II diabetes. Diabetes & vascular disease research. 2015 Jul:12(4):239-48. doi: 10.1177/1479164115580936. Epub 2015 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 25941161]

Barger PM, Kelly DP. Fatty acid utilization in the hypertrophied and failing heart: molecular regulatory mechanisms. The American journal of the medical sciences. 1999 Jul:318(1):36-42 [PubMed PMID: 10408759]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHamirani YS, Kundu BK, Zhong M, McBride A, Li Y, Davogustto GE, Taegtmeyer H, Bourque JM. Noninvasive Detection of Early Metabolic Left Ventricular Remodeling in Systemic Hypertension. Cardiology. 2016:133(3):157-62. doi: 10.1159/000441276. Epub 2015 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 26594908]

Wolk MJ, Bailey SR, Doherty JU, Douglas PS, Hendel RC, Kramer CM, Min JK, Patel MR, Rosenbaum L, Shaw LJ, Stainback RF, Allen JM, American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. ACCF/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2013 multimodality appropriate use criteria for the detection and risk assessment of stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Feb 4:63(4):380-406. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.009. Epub 2013 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 24355759]

Boellaard R, O'Doherty MJ, Weber WA, Mottaghy FM, Lonsdale MN, Stroobants SG, Oyen WJ, Kotzerke J, Hoekstra OS, Pruim J, Marsden PK, Tatsch K, Hoekstra CJ, Visser EP, Arends B, Verzijlbergen FJ, Zijlstra JM, Comans EF, Lammertsma AA, Paans AM, Willemsen AT, Beyer T, Bockisch A, Schaefer-Prokop C, Delbeke D, Baum RP, Chiti A, Krause BJ. FDG PET and PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour PET imaging: version 1.0. European journal of nuclear medicine and molecular imaging. 2010 Jan:37(1):181-200. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1297-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19915839]

Depre C,Vanoverschelde JL,Taegtmeyer H, Glucose for the heart. Circulation. 1999 Feb 2; [PubMed PMID: 9927407]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDemeure F, Hanin FX, Bol A, Vincent MF, Pouleur AC, Gerber B, Pasquet A, Jamar F, Vanoverschelde JL, Vancraeynest D. A randomized trial on the optimization of 18F-FDG myocardial uptake suppression: implications for vulnerable coronary plaque imaging. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2014 Oct:55(10):1629-35. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.138594. Epub 2014 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 25082852]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNakazato R, Berman DS, Alexanderson E, Slomka P. Myocardial perfusion imaging with PET. Imaging in medicine. 2013 Feb 1:5(1):35-46 [PubMed PMID: 23671459]

Koepfli P, Hany TF, Wyss CA, Namdar M, Burger C, Konstantinidis AV, Berthold T, Von Schulthess GK, Kaufmann PA. CT attenuation correction for myocardial perfusion quantification using a PET/CT hybrid scanner. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2004 Apr:45(4):537-42 [PubMed PMID: 15073247]

Dhar R, Ananthasubramaniam K. Rubidium-82 cardiac positron emission tomography imaging: an overview for the general cardiologist. Cardiology in review. 2011 Sep-Oct:19(5):255-63. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318224253e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21808169]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFathala A, Aboulkheir M, Shoukri MM, Alsergani H. Diagnostic accuracy of (13)N-ammonia myocardial perfusion imaging with PET-CT in the detection of coronary artery disease. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 2019 Feb:9(1):35-42. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2018.10.12. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30881875]

Knuuti J, Kajander S, Mäki M, Ukkonen H. Quantification of myocardial blood flow will reform the detection of CAD. Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. 2009 Jul-Aug:16(4):497-506. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9101-1. Epub 2009 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 19495903]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoody JB, Poitrasson-Rivière A, Hagio T, Buckley C, Weinberg RL, Corbett JR, Murthy VL, Ficaro EP. Added value of myocardial blood flow using (18)F-flurpiridaz PET to diagnose coronary artery disease: The flurpiridaz 301 trial. Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. 2021 Oct:28(5):2313-2329. doi: 10.1007/s12350-020-02034-2. Epub 2020 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 32002847]

Tillisch J, Brunken R, Marshall R, Schwaiger M, Mandelkern M, Phelps M, Schelbert H. Reversibility of cardiac wall-motion abnormalities predicted by positron tomography. The New England journal of medicine. 1986 Apr 3:314(14):884-8 [PubMed PMID: 3485252]

Nakazato R, Berman DS, Dey D, Le Meunier L, Hayes SW, Fermin JS, Cheng VY, Thomson LE, Friedman JD, Germano G, Slomka PJ. Automated quantitative Rb-82 3D PET/CT myocardial perfusion imaging: normal limits and correlation with invasive coronary angiography. Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. 2012 Apr:19(2):265-76. doi: 10.1007/s12350-011-9496-3. Epub 2011 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 22203445]

Lubberink M, Harms HJ, Halbmeijer R, de Haan S, Knaapen P, Lammertsma AA. Low-dose quantitative myocardial blood flow imaging using 15O-water and PET without attenuation correction. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2010 Apr:51(4):575-80. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.070748. Epub 2010 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 20237035]

Rosas EA, Slomka PJ, García-Rojas L, Calleja R, Jácome R, Jiménez-Santos M, Romero E, Meave A, Berman DS. Functional impact of coronary stenosis observed on coronary computed tomography angiography: Comparison with ¹³N-ammonia PET. Archives of medical research. 2010 Nov:41(8):642-8. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2010.11.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21199734]

Kaster T, Mylonas I, Renaud JM, Wells GA, Beanlands RS, deKemp RA. Accuracy of low-dose rubidium-82 myocardial perfusion imaging for detection of coronary artery disease using 3D PET and normal database interpretation. Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. 2012 Dec:19(6):1135-45. doi: 10.1007/s12350-012-9621-y. Epub 2012 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 22996831]

Gould KL, Pan T, Loghin C, Johnson NP, Guha A, Sdringola S. Frequent diagnostic errors in cardiac PET/CT due to misregistration of CT attenuation and emission PET images: a definitive analysis of causes, consequences, and corrections. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2007 Jul:48(7):1112-21 [PubMed PMID: 17574974]

Nordberg P, Declerck J, Brady M. Pre-reconstruction rigid body registration for positron emission tomography: an initial validation against ground truth. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Annual International Conference. 2010:2010():5612-5. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2010.5626800. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21096491]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBeanlands RS, Chow BJ, Dick A, Friedrich MG, Gulenchyn KY, Kiess M, Leong-Poi H, Miller RM, Nichol G, Freeman M, Bogaty P, Honos G, Hudon G, Wisenberg G, Van Berkom J, Williams K, Yoshinaga K, Graham J, Canadian Cardiovascular Society, Canadian Association of Radiologists, Canadian Association of Nuclear Medicine, Canadian Nuclear Cardiology Society, Canadian Society of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance. CCS/CAR/CANM/CNCS/CanSCMR joint position statement on advanced noninvasive cardiac imaging using positron emission tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and multidetector computed tomographic angiography in the diagnosis and evaluation of ischemic heart disease--executive summary. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2007 Feb:23(2):107-19 [PubMed PMID: 17311116]

Klingensmith WC 3rd, Noonan C, Goldberg JH, Buchwald D, Kimball JT, Manson SM. Decreased perfusion in the lateral wall of the left ventricle in PET/CT studies with 13N-ammonia: evaluation in healthy adults. Journal of nuclear medicine technology. 2009 Dec:37(4):215-9. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.109.062059. Epub 2009 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 19914976]

Nekolla SG, Miethaner C, Nguyen N, Ziegler SI, Schwaiger M. Reproducibility of polar map generation and assessment of defect severity and extent assessment in myocardial perfusion imaging using positron emission tomography. European journal of nuclear medicine. 1998 Sep:25(9):1313-21 [PubMed PMID: 9724382]

Porenta G, Kuhle W, Czernin J, Ratib O, Brunken RC, Phelps ME, Schelbert HR. Semiquantitative assessment of myocardial blood flow and viability using polar map displays of cardiac PET images. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 1992 Sep:33(9):1628-36 [PubMed PMID: 1517836]

Schelbert HR, Beanlands R, Bengel F, Knuuti J, Dicarli M, Machac J, Patterson R. PET myocardial perfusion and glucose metabolism imaging: Part 2-Guidelines for interpretation and reporting. Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. 2003 Sep-Oct:10(5):557-71 [PubMed PMID: 14569249]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKazakauskaitė E, Žaliaduonytė-Pekšienė D, Rumbinaitė E, Keršulis J, Kulakienė I, Jurkevičius R. Positron Emission Tomography in the Diagnosis and Management of Coronary Artery Disease. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2018 Jul 11:54(3):. doi: 10.3390/medicina54030047. Epub 2018 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 30344278]

Robson PM, Dey D, Newby DE, Berman D, Li D, Fayad ZA, Dweck MR. MR/PET Imaging of the Cardiovascular System. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging. 2017 Oct:10(10 Pt A):1165-1179. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.07.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28982570]

Bengel FM, Higuchi T, Javadi MS, Lautamäki R. Cardiac positron emission tomography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009 Jun 30:54(1):1-15. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.065. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19555834]