Introduction

The middle layer of the eye, also known as the uvea (uva or "grape" in Greek), is made up of the iris, the ciliary body, and the choroid. Uveitis is an inflammation of the middle layer of the eye which can involve one, two, or all three parts of the uveal tract. It can be classified in several ways; anatomically into anterior, intermediate, posterior, or panuveitis according to the site of inflammation, etiologically into infectious or non-infectious uveitis according to the underlying cause, and histopathologically into granulomatous or non-granulomatous uveitis according to the immunological response of the body to the cause of uveitis.[1]

Because many conditions, both ocular and systemic, may result in uveitis, these classifications are important as they may help in narrowing down the differential diagnosis in a case of uveitis since each condition usually presents a characteristic clinical picture. In this article, we will review the multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and management of granulomatous uveitis.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Many conditions can result in granulomatous inflammation of the uveal tract including infectious and non-infectious conditions.

Infectious Causes

- Tuberculosis

- Syphilis

- Herpes viruses[2]

- Cytomegalovirus[3]

- Lyme disease[4]

- Toxoplasmosis[5]

- Toxocariasis[6]

- Trematodes[7]

- Propionibacterium acnes[8]

- Post-streptococcal infections[9]

- Some fungal infections including following coronavirus disease-2019: candida, histoplasmosis, and cryptococcosis[10][11][12][11][13][11]

Non-infectious Causes

- Sarcoidosis[14][15]

- Multiple sclerosis[16]

- Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease[17]

- Sympathetic ophthalmia[18]

- Lymphoma[19]

- Blau syndrome[20]

- Histiocytosis[21]

- Granuloma annulare[22]

- Lens-induced[23]

- Drug-induced: brimonidine and pembrolizumab, [24][25]

- Idiopathic (as multifocal choroiditis),[26]

- Common variable immune deficiency[27]

- Juvenile idiopathic arthritis[28]

- High-density silicone oil tamponade[29]

- Intraocular foreign bodies including caterpillar hair[30][31]

- Tattoo-associated granulomatous uveitis[32][32]

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of granulomatous uveitis depends on several factors, including etiologic, geographic, and ethnic factors. For example, in areas that are endemic to tuberculosis, such as some developing countries as India and Egypt, tuberculosis is a common cause of granulomatous uveitis. At the same time, it is rare in developed countries such as the United States. However, cases of tuberculous uveitis have resurged in the United States following the HIV epidemic.[33][34][35][36]

Sarcoidosis may be more common in Blacks than in Whites but less common in Asians than in Whites. At the same time, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease is a common cause of non-infectious uveitis among Asians.[37][38] Toxoplasmosis is also a common cause of uveitis in Asia, South America, Central America, and parts of Africa.[38][39][40] Trematode-induced granulomatous uveitis is particularly common in Egypt and India, while Lyme disease is common in North America and Europe.[41][42] Blau syndrome occurs primarily in Whites.[43]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of granulomatous uveitis depends on the underlying cause. However, a similar general mechanism is responsible for forming granulomas in most granulomatous inflammations regardless of the causative antigen. Tissue-resident antigen-presenting cells, such as dendritic cells and monocytes circulating in the blood, are responsible for first detecting an antigen, which is then presented to T helper cells, which in turn results in recruitment and activation of more circulating monocytes and lymphocytes into the affected tissue, with the production of various cytokines and chemokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma that are responsible for regulating granulomatous immune responses, and the formation of epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells by the activated macrophages. These cells assemble around the culprit antigen, leading to granuloma formation.[44][45][46]

This antigen may be of bacterial origin as in tuberculosis or of unknown origin as in sarcoidosis.[47] In lymphoma cases, inflammation may be due to a host immune response to lymphomatous cells or a paraneoplastic granulomatous inflammation. In contrast, in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and sympathetic ophthalmia, the altered immune response may be directed towards melanocytes.[19][48]

Impairment in the immunosuppressive role of regulatory T cells may also contribute to the exaggerated immune response in granulomatous uveitis. Simultaneously, specific HLA class II antigens may play a role in the development of granulomatous inflammation.[47] Blau syndrome is a monogenic familial autoinflammatory systemic granulomatous disease associated with a mutation in the NOD2 gene. This gene encodes a protein that is a member of the pattern-recognition intracellular receptor family, expressed in macrophages, monocytes, and dendritic cells, and plays an important role in the innate immune defense system against pathogens.[43]

The mutation leads to the unfolding of the NOD2 protein from its autoinhibited state, leading to the hyperactivation of nuclear factor kappa B and the excessive production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which results in systemic granulomatous inflammation, including skin rash, arthritis, and granulomatous uveitis.[49]

Histopathology

Microscopically, granulomas consist of macrophages, epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes that may involve any part of the uveal tract. Granulomatous inflammation of the uvea is typically divided into three distinct morphologic categories: zonal, sarcoidal, and diffuse. In tuberculous uveitis, histopathology of microbiologically proven cases reveals zonal granulomatous inflammation of the uvea with central caseous necrosis that occasionally contains acid-fast bacilli.[50]

At the same time, in sarcoidal granulomas, they are typically non-caseating.[51] There may also be perivascular granulomas surrounding the retinal vessels in cases of retinal vasculitis with T-cell infiltration.[50] Fungal infections, foreign bodies, lymphomas, and tattoo-associated uveitis may also result in granulomatous inflammation of the sarcoidal type.[48][52][53]

In diffuse granulomatous inflammation, there is diffuse lymphocytic infiltration throughout the uvea with focal collections of epithelioid cells and occasionally multinucleated giant cells. Examples of diffuse granulomatous inflammation include Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease and sympathetic ophthalmia, which may also show focal clusters of lymphocytes and epithelioid cells with pigment located between the retina pigment epithelium and Bruch's membrane known as Dalen-Fuchs nodules.[48]

History and Physical

General Examination

Detailed history taking is an integral part of evaluating a patient with uveitis since it will help in directing further examinations and investigations. The history will differ according to the underlying etiology of uveitis. Attention to certain details in a quick review of systems, such as a history of coughing or dyspnea, may provide clues to the diagnosis of tuberculosis or sarcoidosis. In contrast, details in sexual history may point to a diagnosis of syphilis or herpes. A tick bite history with the subsequent development of a bulls-eye rash may indicate Lyme disease, especially when occurring in an endemic area. In contrast, a history of cat exposure may suggest toxoplasmosis. Traveling to an area that is endemic in tuberculosis or having a history of a contralateral eye injury may sometimes be the only clue to the diagnosis. This should be followed by a focused examination performed by a specialist tailored to the main complaints and symptoms of the patient. For example, chest examination of a patient with a history of dyspnea or skin examination of a patient with a history of a rash may help in ordering further imaging or laboratory investigations more efficiently.[54][55]

Ocular Examination

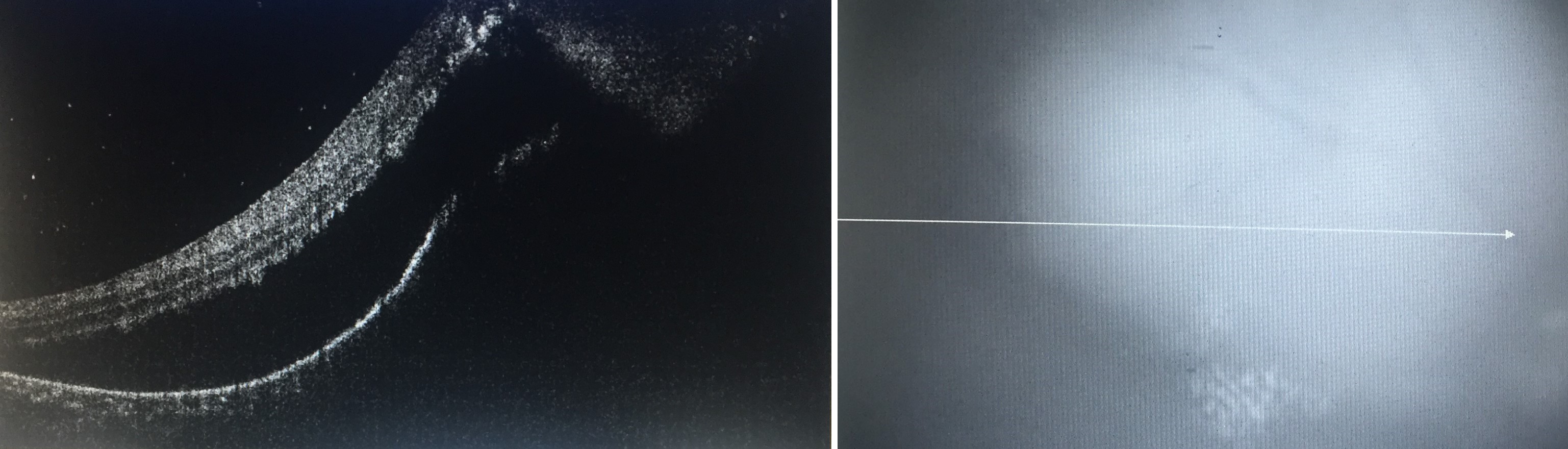

Patients with uveitis usually present with the blurring of vision, ocular pain, redness, and photophobia. These may vary according to the anatomical location of the inflammation. Anterior segment examination of a patient with granulomatous uveitis may reveal ciliary injection, elevated or decreased intraocular pressure, mutton fat keratic precipitates (large deposits on the back of the cornea), anterior chamber flare and cells, iris, and angle granulomas, anterior and posterior synechia, cataract especially posterior subcapsular, cataract surgery in phakoanaphylactic uveitis and anterior vitreous cells. Some signs may also be present that indicate specific etiologies such as corneal scars and iris atrophy in herpetic uveitis, vascularized iris nodules known as roseola in syphilis, and an anterior chamber granuloma in trematode uveitis.[56][7]

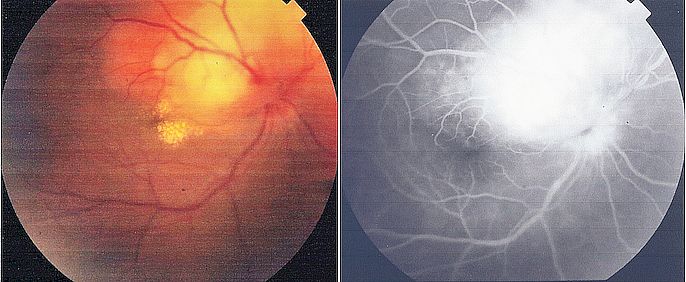

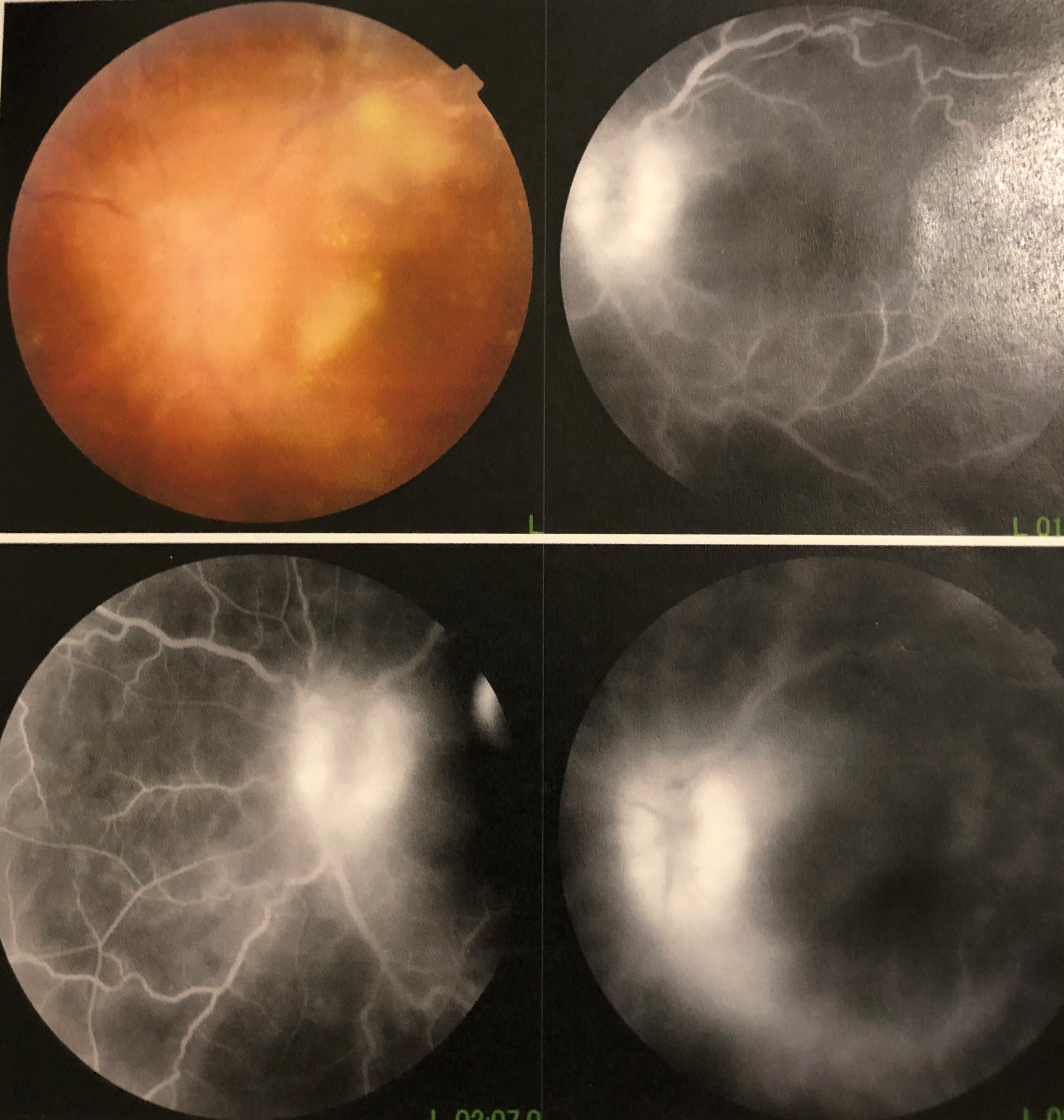

Posterior segment examination may show vitritis, vitreous opacities, snowballs, snow banking in intermediate uveitis, perivascular exudates, retinal hemorrhages in retinal vasculitis, cystoid macular edema, and optic disc edema, as well as posterior segment complications such as choroidal neovascularization, retinal neovascularization, and epiretinal membrane.[57] Certain posterior segment signs may be associated with specific conditions such as sunset glow fundus in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease, focal chorioretinitis adjacent to an area of old chorioretinal scarring in toxoplasmosis, optic disc granulomas in sarcoidosis, and a choroidal granuloma in tuberculosis (tuberculoma).[15][17][58]

Diagnostic Criteria

When available, the use of diagnostic criteria may assist in the diagnosis of specific causes of granulomatous uveitis[59]. These criteria usually include a combination of clinical and investigative findings.[60]

Evaluation

Systemic Investigations

Laboratory Investigations

Laboratory investigations should be directed towards the most probable cause of uveitis according to the patient's history and clinical picture. Knowledge of each test's positive and negative predictive value is particularly important to help reach the correct diagnosis and avoid false-positive and false-negative test results that may lead to an incorrect diagnosis and improper treatment. General investigations to be performed include complete blood picture, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C reactive protein level.

Investigations for infectious causes include tuberculin skin testing and Quantiferon-TB Gold for tuberculosis, venereal disease research laboratory test, rapid plasma reagin test, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test, and the microhemagglutination assay for treponema pallidum for syphilis, serum IgM and IgG antibodies against herpes and cytomegaloviruses, serum IgM and IgG antibodies against Borrelia and Toxoplasma using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, detection of antibodies against Histoplasma and Cryptococcus, and blood cultures for systemic bacterial and fungal infections.[61][62][63]

Investigations for non-infectious causes include serum angiotensin-converting enzyme and calcium levels for sarcoidosis and cerebrospinal fluid analysis for oligoclonal bands in multiple sclerosis. Some investigations may be required before starting specific medications, such as tuberculin skin testing before initiating anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment or testing for thiopurine S-methyltransferase polymorphisms in patients starting azathioprine therapy.[64][65][66][67]

Imaging

Imaging is required in the diagnosis or exclusion of several infectious and non-infectious causes of granulomatous uveitis such as chest x-ray or computed tomography scan of the chest for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis or sarcoidosis, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spine for the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis or central nervous system lymphoma, and computed tomography scan of the abdomen for abdominal sarcoidosis or lymphoma.[68][69] Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography scanning may help in the diagnosis of tuberculosis and sarcoidosis.[70][71] Specific investigations may be needed to exclude systemic complications associated with certain multisystemic conditions such as electrocardiography and echocardiography in cardiac sarcoidosis and MRI of the spine in Pott disease.[72][73]

Tissue Biopsy

A tissue biopsy, when available, is the gold standard for the diagnosis of several conditions associated with granulomatous uveitis by either allowing the detection of the causative organism by using special stains such as the Ziehl-Neelsen stain for Mycobacterium tuberculosis and fungal stains or by allowing the detection of characteristic histopathologic features associated with the condition such as non-caseating granulomas in sarcoidosis.[74] Tissue biopsy may also allow polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing or the culture of the causative organism to facilitate its detection.[75] Other uveitis-causing conditions mainly diagnosed using tissue biopsy include lymphoma and histiocytosis.[19][21]

Ocular Investigations

Laboratory Investigations

Aqueous humor sampling through anterior chamber paracentesis or vitreous humor sampling through a vitreous tap may allow the diagnosis of infectious and non-infectious causes of uveitis. The sample can be tested using western blotting to detect local antibody production to a specific organism, or it can be used to determine the Goldmann-Witmer coefficient.[76] PCR testing can also be used to amplify and identify the DNA or RNA of various viruses, bacteria, parasites, and fungi.[77] Both real-time PCR and multiplex PCR are useful and have their own set of advantages.[78] Cytopathological examination and microbiological testing of the sample can also be performed. Interleukin 10-to-interleukin 6 ratio obtained from aqueous or vitreous samples can be used to diagnose primary intraocular lymphoma.[79]

Imaging

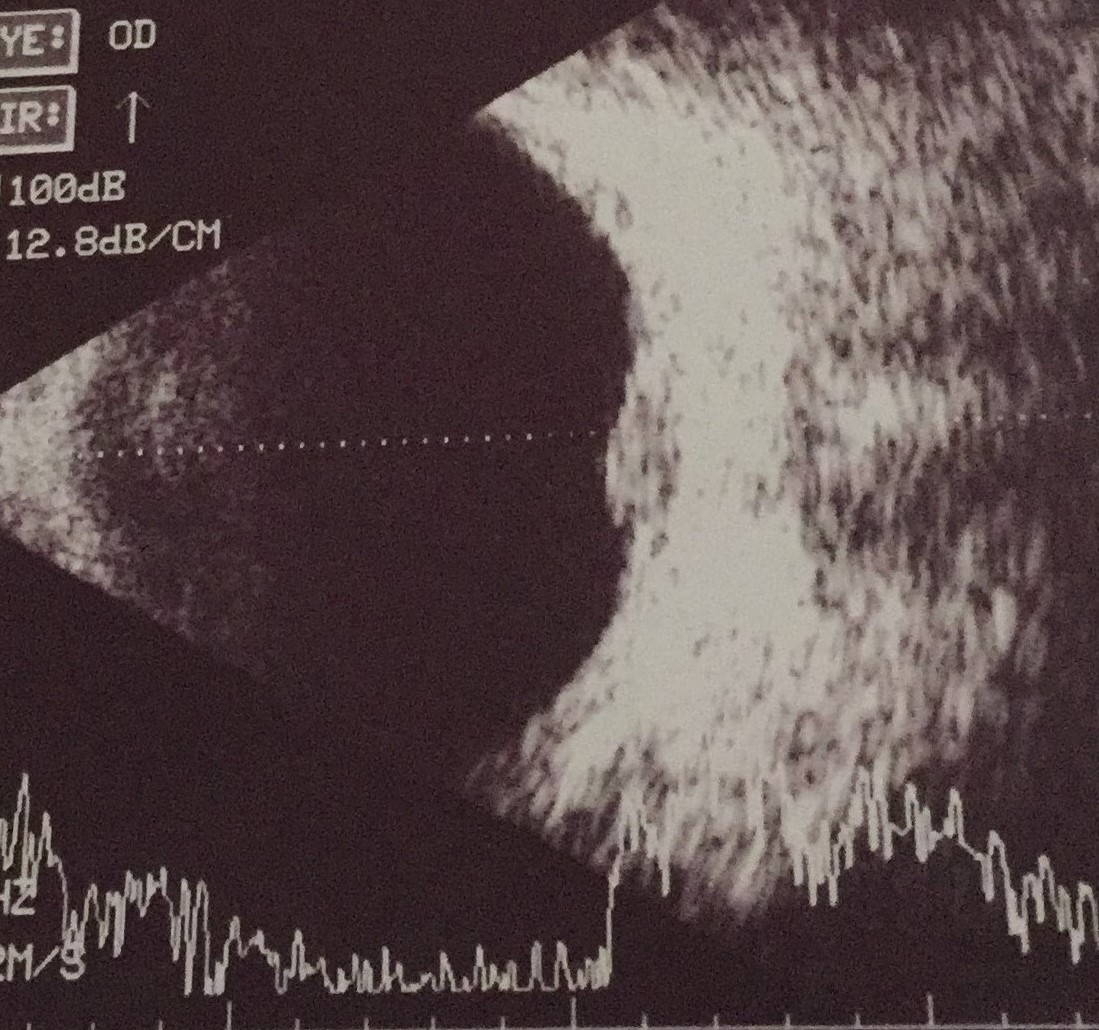

Ocular B-scan ultrasonography may be used in cases with media opacities obscuring fundus examination such as cataracts or severe anterior chamber reaction to evaluate posterior segment involvement. Laser flare meter and ocular fluorometry may be used to allow an objective measure of aqueous flare in uveitis.[80][81] Confocal microscopy can be used to differentiate between granulomatous and non-granulomatous keratic precipitates.[82]

Fluorescein angiography, including wide-field imaging, may assist in the evaluation of papillitis, optic disc granulomas, cystoid macular edema, choroiditis, choroidal neovascularization, and retinal vasculitis, while optical coherence tomography may be useful in the evaluation and follow up of cystoid macular edema, epiretinal membranes, and choroidal neovascularization, and in the evaluation of the choroid using enhanced depth imaging.[15][83]

Optical coherence tomography angiography allows the non-invasive evaluation of the foveal avascular zone, areas of retinal ischemia, and choroidal neovascular membranes without obscuration by dye leakage or macular xanthophyll pigments.[84][85] Indocyanine green angiography may allow enhanced imaging of choroidal lesions in cases of posterior uveitis.[86]

Tissue Biopsy

Biopsy of ocular tissues may also help diagnose the cause of granulomatous uveitis, but its use varies depending on the suspected underlying etiology. For example, a biopsy of the conjunctiva, whether directed or non-directed, is a simple and inexpensive method that may assist in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, while a chorioretinal biopsy is a complex procedure that may help provide useful information in patients with progressive chorioretinal lesions with an unknown etiology despite extensive testing.[87][88][89][90]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of granulomatous uveitis includes local (ocular) and systemic treatment and treatment of complications:

Ocular Treatment

Ocular treatment involves non-specific topical treatment for inflammation, such as topical steroids and cycloplegics. Periocular and intravitreal steroid injections, including steroid implants, may be given to rapidly and consistently control inflammation in non-infectious conditions or infectious conditions under appropriate anti-microbial cover.[91][92][93] (B2)

Intravitreal antimicrobial injections may be used, such as clindamycin for toxoplasma, and antifungals such as voriconazole for candida to achieve higher intraocular concentrations a better therapeutic response.[94] Intravitreal immunosuppressants such as sirolimus may also be used in the treatment of non-infectious uveitis.[95][96] Surgical aspiration may be useful in lens-induced (phakoanaphylactic) cases or cases associated with large trematodal anterior chamber granulomas.[97](B2)

Systemic Treatment

Systemic treatment is needed to control the systemic condition associated with uveitis and is directed towards the causative etiology. This is also associated with the improvement of ocular disease. Systemic steroids and immunomodulatory agents such as azathioprine, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil are used in non-infectious conditions such as Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada and sarcoidosis.[15][98]

In contrast, systemic antimicrobials are used to treat infectious conditions such as anti-tuberculous agents for tuberculosis, penicillin for syphilis, and acyclovir for herpetic uveitis.[99][100][101] Biological agents such as tumor necrosis factor inhibitors may also be useful in some non-infectious conditions.[102][103] In case of drug-induced uveitis, the offending drug should be discontinued.(A1)

Treatment of Complications

Treatment of complications includes cataract extraction with or without intraocular lens implantation.[104][105][106] Glaucoma can be treated medically using various topical and systematic medications or surgically if necessary. Some clinicians recommend avoiding prostaglandin analogs in cases of uveitis associated with active inflammation or cystoid macular edema, while other studies showed it to be a safe option.[107][108][109](B2)

Surgical treatment of glaucoma includes iridectomy, trabeculectomy, and glaucoma drainage devices. Some studies suggest that glaucoma drainage devices could be more effective than trabeculectomy for uveitic glaucoma over the long term, while other studies showed equal efficacy.[110][111] The use of glaucoma shunts may also possibly improve the outcome of trabeculectomy in uveitic glaucoma cases.[112] Intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents such as bevacizumab or ranibizumab may be used to treat cystoid macular edema and choroidal neovascularization associated with granulomatous uveitis.[113][114][115] (B2)

Laser photocoagulation can be used to treat retinal ischemia associated with retinal neovascularization to prevent vitreous hemorrhage and fibrovascular proliferation [116]. At the same time, pars plana vitrectomy can be performed in cases complicated by non-resolving vitreous hemorrhage, vitreous opacities, epiretinal membranes, and macular holes.[117][118](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Drugs used in the treatment of uveitis may have serious side effects. Steroids may result in cataract formation, glaucoma, hyperglycemia, and osteoporosis. Azathioprine may lead to myelosuppression and pancytopenia, while methotrexate may result in hepatotoxicity.[127][128]

Anti-tumor necrosis factors such as infliximab may cause the reactivation of latent tuberculosis, while anti-tuberculous treatment may also lead to toxicity such as ethambutol-associated optic neuropathy and the hepatotoxicity associated with isoniazid treatment.[129] Pyrimethamine, which is used in the treatment of toxoplasmosis, may be associated with bone marrow suppression.[130][131]

Prognosis

The prognosis of granulomatous uveitis depends on the underlying condition and its severity. Early and appropriate diagnosis and treatment may lead to a marked improvement of the condition and avoidance of vision and life-threatening complications.

Complications

- Cataract especially posterior subcapsular

- Posterior synechia and seclusio pupillae

- Peripheral anterior synechia

- Cyclitic membrane

- Ocular hypotony [132][133]

- Secondary open-angle glaucoma

- Secondary closed-angle glaucoma

- Steroid-induced glaucoma [134]

- Cystoid macular edema [115]

- Epiretinal membrane [118]

- Choroidal neovascularization [135]

- Retinal vasculitis

- Retinal neovascularization [135]

- Vitreous hemorrhage

- Retinal detachment [116]

- Macular hole [118]

- Band keratopathy

- Amblyopia

- Systemic complications associated with the underlying disease such as arrhythmias in cardiac sarcoidosis[136]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with granulomatous uveitis should be educated on their conditions, including their ocular and systemic manifestations and complications, their treatment and prognosis, and the complication of their treatment. Compliance with follow-up and treatment in patients with granulomatous uveitis is of utmost importance to follow up and control the disease activity, allow early detection and management of ocular complications, and monitor for systemic complications well as complications of local and systemic treatment. Patients on systemic medications may need to undergo routine laboratory testing to monitor for drug-induced adverse events.

Pearls and Other Issues

Granulomatous uveitis can be caused by many conditions, both infectious and non-infectious, which can be differentiated based on history, examination, and investigative findings. It is important to promptly exclude infectious causes of uveitis to allow the early institution of anti-inflammatory treatment using steroids and immunomodulatory agents, including in idiopathic cases, to allow the early and rapid control of inflammation and to improve prognosis.

If an infectious etiology is identified or suspected, steroid and immunomodulatory treatment may be commenced only after appropriate anti-microbial agents are initiated to avoid exacerbation of the condition.[137] In fact, the use of steroids and immunomodulatory agents in these conditions, in addition to the appropriate anti-microbial therapy, may be necessary to avoid the paradoxical worsening of inflammation that is known to occur following the treatment of infectious uveitis.[138][139][140]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of granulomatous uveitis and the associated systemic disease is challenging. It frequently requires the collaboration of an interprofessional team of specialists consisting of ophthalmologists, infectious disease specialists, pulmonologists, internists, rheumatologists, and dermatologists. The nurses are also vital members of this interprofessional group as they will monitor the patient's vital signs and assist with the patient and family's education.

Frequent and effective communication between the ophthalmologist and the systemic disease specialists is vital in managing granulomatous uveitis as frequently the ophthalmologist will be the one monitoring the ocular disease activity prescribing local ocular treatment. In contrast, a systemic disease specialist will prescribe the systemic treatment and monitor its systemic adverse events and systemic disease activity. Both uveitis and systemic disease specialists must be involved in the initial evaluation of a patient with uveitis to direct further testing and allow an accurate diagnosis of the underlying condition to formulate an effective management plan.[141]

The use of standardized red flags for the interprofessional referral may also assist in timely referral during follow-ups.[142] This will improve the quality of patient care and optimize treatment outcomes while minimizing complications and side effects of treatment. The evidence level available for granulomatous uveitis management varies and ranges from large randomized controlled clinical trials (Level 1) to case series and expert opinion (Level 5).[143][144]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tsirouki T, Dastiridou A, Symeonidis C, Tounakaki O, Brazitikou I, Kalogeropoulos C, Androudi S. A Focus on the Epidemiology of Uveitis. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2018:26(1):2-16. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2016.1196713. Epub 2016 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 27467180]

Kardeş E, Bozkurt K, Sezgin Akçay Bİ, Ünlü C, Aydoğan Gezginaslan T, Ergin A. Clinical Features and Prognosis of Herpetic Anterior Uveitis. Turkish journal of ophthalmology. 2016 Jun:46(3):109-113 [PubMed PMID: 27800272]

Chan NS, Chee SP, Caspers L, Bodaghi B. Clinical Features of CMV-Associated Anterior Uveitis. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2018:26(1):107-115. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2017.1394471. Epub 2017 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 29172842]

Bernard A, Seve P, Abukhashabh A, Roure-Sobas C, Boibieux A, Denis P, Broussolle C, Mathis T, Kodjikian L. Lyme-associated uveitis: Clinical spectrum and review of literature. European journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Sep:30(5):874-885. doi: 10.1177/1120672119856943. Epub 2019 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 31238716]

Hall BR, Oliver GE, Wilkinson M. A presentation of longstanding toxoplasmosis chorioretinitis. Optometry (St. Louis, Mo.). 2009 Jan:80(1):23-8. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2008.03.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19111254]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWoodhall D, Starr MC, Montgomery SP, Jones JL, Lum F, Read RW, Moorthy RS. Ocular toxocariasis: epidemiologic, anatomic, and therapeutic variations based on a survey of ophthalmic subspecialists. Ophthalmology. 2012 Jun:119(6):1211-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.12.013. Epub 2012 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 22336630]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmin RM,Goweida MB,El Goweini HF,Bedda AM,Lotfy WM,Gaballah AH,Nadar AA,Radwan AE, Trematodal granulomatous uveitis in paediatric Egyptian patients: a case series. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2017 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 28600298]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHuynh TH, Johnson MW. Delayed posttraumatic Propionibacterium acnes endophthalmitis in a child. Ophthalmic surgery, lasers & imaging : the official journal of the International Society for Imaging in the Eye. 2006 Jul-Aug:37(4):314-6. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20060701-09. Epub [PubMed PMID: 16898393]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBesada E, Frauens BJ. Unilateral granulomatous post-streptococcal uveitis with elevated tension. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 2008 Nov:85(11):E1110-5. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e31818b9622. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18981915]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKlintworth GK, Hollingsworth AS, Lusman PA, Bradford WD. Granulomatous choroiditis in a case of disseminated histoplasmosis. Histologic demonstration of Histoplasma capsulatum in choroidal lesions. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1973 Jul:90(1):45-8 [PubMed PMID: 4714795]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlzahrani YA, Aziz HA, Shrestha NK, Biscotti CV, Singh AD. Cryptococcal iridociliary granuloma. Survey of ophthalmology. 2016 Jul-Aug:61(4):498-501. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2015.12.005. Epub 2015 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 26731486]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRao NA, Nerenberg AV, Forster DJ. Torulopsis candida (Candida famata) endophthalmitis simulating Propionibacterium acnes syndrome. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1991 Dec:109(12):1718-21 [PubMed PMID: 1841584]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBhagali R, Prabhudesai NP, Prabhudesai MN. Post COVID-19 opportunistic candida retinitis: A case report. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2021 Apr:69(4):987-989. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_3047_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33727474]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNiederer RL, Ma SP, Wilsher ML, Ali NQ, Sims JL, Tomkins-Netzer O, Lightman SL, Lim LL. Systemic Associations of Sarcoid Uveitis: Correlation With Uveitis Phenotype and Ethnicity. American journal of ophthalmology. 2021 Sep:229():169-175. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.003. Epub 2021 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 33737030]

Elnahry AG, Elnahry GA. Abdominal sarcoidosis presenting as bilateral simultaneous optic disc granulomas. Neuro-ophthalmology (Aeolus Press). 2019 Apr:43(2):91-94. doi: 10.1080/01658107.2018.1467935. Epub 2018 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 31312232]

Zein G, Berta A, Foster CS. Multiple sclerosis-associated uveitis. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2004 Jun:12(2):137-42 [PubMed PMID: 15512983]

O'Keefe GA, Rao NA. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. Survey of ophthalmology. 2017 Jan-Feb:62(1):1-25. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.05.002. Epub 2016 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 27241814]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChang GC, Young LH. Sympathetic ophthalmia. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2011 Jul-Sep:26(4-5):316-20. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2011.588658. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21958181]

Alshamrani AA, Alsarhani WK, Aljasser AA, Rubio-Caso MJ. Granulomatous panuveitis associated with Hodgkin lymphoma: A case report with review of the literature. European journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Jan:32(1):NP102-NP108. doi: 10.1177/1120672120969036. Epub 2020 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 33153312]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWouters CH, Maes A, Foley KP, Bertin J, Rose CD. Blau syndrome, the prototypic auto-inflammatory granulomatous disease. Pediatric rheumatology online journal. 2014:12():33. doi: 10.1186/1546-0096-12-33. Epub 2014 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 25136265]

Moreker MR, Dudani AI, Sharma TR, Patel K, Smruti BK. Isolated intraocular histiocytosis-A rarely reported entity masquerading clinically as uveitis. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Sep:68(9):2054-2056. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_565_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32823479]

Reddy HS, Khurana RN, Rao NA, Chopra V. Granuloma annulare anterior uveitis. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2008 Jan-Feb:16(1):55-7. doi: 10.1080/09273940801899814. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18379945]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVandenbroucke S, Foets B, Wouters C, Casteels I. Bilateral congenital cataract with suspected lens-induced granulomatous uveitis. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2014 Oct:18(5):492-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2014.05.010. Epub 2014 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 25262559]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceComet A, Donnadieu B, Courjaret JC, Gascon P, Denis D, Matonti F. [Brimonidine and acute anterior granulomatous uveitis: A case report and literature review]. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2017 Apr:40(4):e127-e129. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2016.01.016. Epub 2017 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 28336279]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLise QK, Audrey AG. Multifocal choroiditis as the first sign of systemic sarcoidosis associated with pembrolizumab. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2017 Apr:5():92-93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2016.12.014. Epub 2016 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 29503956]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKanavi MR, Soheilian M, Naghshgar N. Confocal scan of keratic precipitates in uveitic eyes of various etiologies. Cornea. 2010 Jun:29(6):650-4. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181c2967e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20458232]

Carter S, Xie K, Knight D, Minckler D, Kedhar S. Granulomatous Uveitis and Conjunctivitis Due to Common Variable Immune Deficiency: A Case Report. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2019:27(7):1124-1126. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2018.1497666. Epub 2018 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 30142001]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePapasavvas I, Herbort CP Jr. Granulomatous Features in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis-Associated Uveitis is Not a Rare Occurrence. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2021:15():1055-1059. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S299436. Epub 2021 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 33727787]

Theelen T, Tilanus MA, Klevering BJ. Intraocular inflammation following endotamponade with high-density silicone oil. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2004 Jul:242(7):617-20 [PubMed PMID: 15029505]

Mahmoud A, Messaoud R, Abid F, Ksiaa I, Bouzayene M, Khairallah M. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography and retained vegetal intraocular foreign body masquerading as chronic anterior uveitis. Journal of ophthalmic inflammation and infection. 2017 Dec:7(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12348-017-0130-7. Epub 2017 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 28536985]

Doshi PY, Usgaonkar U, Kamat P. A Hairy Affair: Ophthalmia nodosa Due to Caterpillar Hairs. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2018:26(1):136-141. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2016.1199708. Epub 2016 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 27438993]

Ostheimer TA, Burkholder BM, Leung TG, Butler NJ, Dunn JP, Thorne JE. Tattoo-associated uveitis. American journal of ophthalmology. 2014 Sep:158(3):637-43.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.05.019. Epub 2014 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 24875002]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBiswas J, Kharel Sitaula R, Multani P. Changing uveitis patterns in South India - Comparison between two decades. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Apr:66(4):524-527. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_851_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29582812]

Abd El Latif E, Abdelhalim AS, Montasser AS, Said MH, Shikhoun Ahmed M, Abdel Kader Fouly Galal M, Ibrahim W, Samy Abd Elaziz M, Fathi Abuelkheir A, Elbarbary H, Elsayed AMA, Lotfy A, Elmorsy OA, Gab-Alla AA, Hatata RM, Abousamra AAH, Farouk MM, Elbakary MA, Awara AM, Amer I, Elzawahry WMAE, Kandil HW, Barrada OA, Bakr Elessawy K, Zayed MA, El Hennawi H, Tawfik MA. Pattern of Intermediate Uveitis in an Egyptian Cohort. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2020 Apr 2:28(3):524-531. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2019.1668429. Epub 2019 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 31642742]

Bajema KL, Pakzad-Vaezi K, Hawn T, Pepple KL. Tuberculous uveitis: association between anti-tuberculous therapy and clinical response in a non-endemic country. Journal of ophthalmic inflammation and infection. 2017 Oct 4:7(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12348-017-0137-0. Epub 2017 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 28980216]

Laovirojjanakul W, Thanathanee O. Opportunistic ocular infections in the setting of HIV. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2018 Nov:29(6):558-565. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000531. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30169465]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUngprasert P, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of sarcoidosis: an update from a population-based cohort study from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Reumatismo. 2017 May 22:69(1):16-22. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2017.965. Epub 2017 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 28535617]

Abaño JM, Galvante PR, Siopongco P, Dans K, Lopez J. Review of Epidemiology of Uveitis in Asia: Pattern of Uveitis in a Tertiary Hospital in the Philippines. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2017:25(sup1):S75-S80. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2017.1335755. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29083984]

Al Dhibi HA, Al Shamsi HN, Al-Mahmood AM, Al Taweel HM, Al Shamrani MA, Arevalo JF, Gupta V, The Kkesh Uveitis Survey Study Group. Patterns of Uveitis in a Tertiary Care Referral Institute in Saudi Arabia. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2017 Jun:25(3):388-395. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2015.1133836. Epub 2016 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 26910754]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePetersen E, Kijlstra A, Stanford M. Epidemiology of ocular toxoplasmosis. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2012 Apr:20(2):68-75. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2012.661115. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22409558]

Mead PS. Epidemiology of Lyme disease. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2015 Jun:29(2):187-210. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25999219]

El Nokrashy A, Abou Samra W, Sobeih D, Lamin A, Hashish A, Tarshouby S, Lightman S, Sewelam A. Treatment of presumed trematode-induced granulomatous anterior uveitis among children in rural areas of Egypt. Eye (London, England). 2019 Oct:33(10):1525-1533. doi: 10.1038/s41433-019-0428-9. Epub 2019 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 30944459]

PaÇ Kisaarslan A, SÖzerİ B, Şahİn N, Özdemİr ÇİÇek S, GÜndÜz Z, Demİrkaya E, Berdelİ A, Sadet Özcan S, PorazoĞlu H, DÜŞÜnsel R. Blau Syndrome and Early-Onset Sarcoidosis: A Six Case Series and Review of the Literature. Archives of rheumatology. 2020 Mar:35(1):117-127. doi: 10.5606/ArchRheumatol.2020.7060. Epub 2019 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 32637927]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJakubzick C, Gautier EL, Gibbings SL, Sojka DK, Schlitzer A, Johnson TE, Ivanov S, Duan Q, Bala S, Condon T, van Rooijen N, Grainger JR, Belkaid Y, Ma'ayan A, Riches DW, Yokoyama WM, Ginhoux F, Henson PM, Randolph GJ. Minimal differentiation of classical monocytes as they survey steady-state tissues and transport antigen to lymph nodes. Immunity. 2013 Sep 19:39(3):599-610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.007. Epub 2013 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 24012416]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCrouser ED, White P, Caceres EG, Julian MW, Papp AC, Locke LW, Sadee W, Schlesinger LS. A Novel In Vitro Human Granuloma Model of Sarcoidosis and Latent Tuberculosis Infection. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2017 Oct:57(4):487-498. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0321OC. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28598206]

Locke LW, Schlesinger LS, Crouser ED. Current Sarcoidosis Models and the Importance of Focusing on the Granuloma. Frontiers in immunology. 2020:11():1719. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01719. Epub 2020 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 32849608]

Broos CE, van Nimwegen M, Hoogsteden HC, Hendriks RW, Kool M, van den Blink B. Granuloma formation in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Frontiers in immunology. 2013 Dec 10:4():437. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00437. Epub 2013 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 24339826]

Rao NA. Pathology of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. International ophthalmology. 2007 Apr-Jun:27(2-3):81-5 [PubMed PMID: 17435969]

Rosé CD, Doyle TM, McIlvain-Simpson G, Coffman JE, Rosenbaum JT, Davey MP, Martin TM. Blau syndrome mutation of CARD15/NOD2 in sporadic early onset granulomatous arthritis. The Journal of rheumatology. 2005 Feb:32(2):373-5 [PubMed PMID: 15693102]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBasu S, Wakefield D, Biswas J, Rao NA. Pathogenesis and Pathology of Intraocular Tuberculosis. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2015 Aug:23(4):353-357. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2015.1056536. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29265968]

Usui Y, Goto H. Granuloma-like formation in deeper retinal plexus in ocular sarcoidosis. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2019:13():895-896. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S200519. Epub 2019 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 31213760]

Du J, Zhang Y, Liu D, Zhu G, Zhang Q. Hodgkin's lymphoma with marked granulomatous reaction: a diagnostic pitfall. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology. 2019:12(7):2772-2774 [PubMed PMID: 31934112]

Kluger N. Tattoo-associated uveitis with or without systemic sarcoidosis: a comparative review of the literature. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2018 Nov:32(11):1852-1861. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15070. Epub 2018 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 29763518]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGrumet P, Kodjikian L, de Parisot A, Errera MH, Sedira N, Heron E, Pérard L, Cornut PL, Schneider C, Rivière S, Ollé P, Pugnet G, Cathébras P, Manoli P, Bodaghi B, Saadoun D, Baillif S, Tieulie N, Andre M, Chiambaretta F, Bonin N, Bielefeld P, Bron A, Mouriaux F, Bienvenu B, Vicente S, Bin S, Labetoulle M, Broussolle C, Jamilloux Y, Decullier E, Sève P, ULISSE group. Contribution of diagnostic tests for the etiological assessment of uveitis, data from the ULISSE study (Uveitis: Clinical and medicoeconomic evaluation of a standardized strategy of the etiological diagnosis). Autoimmunity reviews. 2018 Apr:17(4):331-343. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.10.018. Epub 2018 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 29427823]

de Parisot A, Jamilloux Y, Kodjikian L, Errera MH, Sedira N, Heron E, Pérard L, Cornut PL, Schneider C, Rivière S, Ollé P, Pugnet G, Cathébras P, Manoli P, Bodaghi B, Saadoun D, Baillif S, Tieulie N, André M, Chiambaretta F, Bonin N, Bielefeld P, Bron A, Mouriaux F, Bienvenu B, Amamra N, Guerre P, Decullier E, Sève P, ULISSE group. Evaluating the cost-consequence of a standardized strategy for the etiological diagnosis of uveitis (ULISSE study). PloS one. 2020:15(2):e0228918. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228918. Epub 2020 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 32059021]

McCarron MJ, Albert DM. Iridocyclitis and an iris mass associated with secondary syphilis. Ophthalmology. 1984 Oct:91(10):1264-8 [PubMed PMID: 6542636]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBabu BM, Rathinam SR. Intermediate uveitis. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2010 Jan-Feb:58(1):21-7. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.58469. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20029143]

Aksoy FE, Altan C, Basarir B. Multimodal imaging of a choroidal granuloma as a first sign of tuberculosis. Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy. 2020 Mar:29():101580. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.101580. Epub 2019 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 31629876]

Mochizuki M, Smith JR, Takase H, Kaburaki T, Acharya NR, Rao NA, International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis Study Group. Revised criteria of International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Oct:103(10):1418-1422. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313356. Epub 2019 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 30798264]

Yang P, Zhong Y, Du L, Chi W, Chen L, Zhang R, Zhang M, Wang H, Lu H, Yang L, Zhuang W, Yang Y, Xing L, Feng L, Jiang Z, Zhang X, Wang Y, Zhong H, Jiang L, Zhao C, Li F, Cao S, Liu X, Chen X, Shi Y, Zhao W, Kijlstra A. Development and Evaluation of Diagnostic Criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. JAMA ophthalmology. 2018 Sep 1:136(9):1025-1031. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.2664. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29978190]

Ang M, Htoon HM, Chee SP. Diagnosis of tuberculous uveitis: clinical application of an interferon-gamma release assay. Ophthalmology. 2009 Jul:116(7):1391-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.02.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19576501]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOzdal PC, Berker N, Tugal-Tutkun I. Pars Planitis: Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics, Management and Visual Prognosis. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2015 Oct-Dec:10(4):469-80. doi: 10.4103/2008-322X.176897. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27051493]

Davis JL. Ocular syphilis. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2014 Nov:25(6):513-8. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000099. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25237932]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGodfrey MS, Friedman LN. Tuberculosis and Biologic Therapies: Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Beyond. Clinics in chest medicine. 2019 Dec:40(4):721-739. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2019.07.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31731980]

Schwab M, Schäffeler E, Marx C, Fischer C, Lang T, Behrens C, Gregor M, Eichelbaum M, Zanger UM, Kaskas BA. Azathioprine therapy and adverse drug reactions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: impact of thiopurine S-methyltransferase polymorphism. Pharmacogenetics. 2002 Aug:12(6):429-36 [PubMed PMID: 12172211]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDong XW, Zheng Q, Zhu MM, Tong JL, Ran ZH. Thiopurine S-methyltransferase polymorphisms and thiopurine toxicity in treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World journal of gastroenterology. 2010 Jul 7:16(25):3187-95 [PubMed PMID: 20593505]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLima BR, Nussenblatt RB, Sen HN. Pharmacogenetics of drugs used in the treatment of ocular inflammatory diseases. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology. 2013 Jul:9(7):875-82. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.783818. Epub 2013 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 23521173]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBansal R, Gupta A, Agarwal R, Dogra M, Bhutani G, Gupta V, Dogra MR, Katoch D, Aggarwal AN, Sharma A, Nijhawan R, Nada R, Nahar Saikia U, Dey P, Behera D. Role of CT Chest and Cytology in Differentiating Tuberculosis from Presumed Sarcoidosis in Uveitis. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2019:27(7):1041-1048. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2018.1425460. Epub 2018 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 29420114]

Akpek EK, Ahmed I, Hochberg FH, Soheilian M, Dryja TP, Jakobiec FA, Foster CS. Intraocular-central nervous system lymphoma: clinical features, diagnosis, and outcomes. Ophthalmology. 1999 Sep:106(9):1805-10 [PubMed PMID: 10485554]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDoycheva D, Deuter C, Hetzel J, Frick JS, Aschoff P, Schuelen E, Zierhut M, Pfannenberg C. The use of positron emission tomography/CT in the diagnosis of tuberculosis-associated uveitis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2011 Sep:95(9):1290-4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2010.182659. Epub 2010 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 20935307]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLe Reun S, Poulain M, Perlat A, Mortemousque B. [Role of PET-scan in the positive diagnosis of sarcoidosis in the work-up of uveitis]. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2015 Feb:38(2):103-11. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2014.09.009. Epub 2015 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 25641523]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKusano KF, Satomi K. Diagnosis and treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2016 Feb:102(3):184-90. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-307877. Epub 2015 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 26643814]

Dunn RN, Ben Husien M. Spinal tuberculosis: review of current management. The bone & joint journal. 2018 Apr 1:100-B(4):425-431. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B4.BJJ-2017-1040.R1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29629596]

Herbort CP, Rao NA, Mochizuki M, members of Scientific Committee of First International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis. International criteria for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis: results of the first International Workshop On Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS). Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2009 May-Jun:17(3):160-9. doi: 10.1080/09273940902818861. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19585358]

Bruijnesteijn Van Coppenraet ES, Lindeboom JA, Prins JM, Peeters MF, Claas EC, Kuijper EJ. Real-time PCR assay using fine-needle aspirates and tissue biopsy specimens for rapid diagnosis of mycobacterial lymphadenitis in children. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2004 Jun:42(6):2644-50 [PubMed PMID: 15184446]

Mathis T, Beccat S, Sève P, Peyron F, Wallon M, Kodjikian L. Comparison of immunoblotting (IgA and IgG) and the Goldmann-Witmer coefficient for diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis in immunocompetent patients. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Oct:102(10):1454-1458. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311528. Epub 2018 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 29343531]

Anwar Z, Galor A, Albini TA, Miller D, Perez V, Davis JL. The diagnostic utility of anterior chamber paracentesis with polymerase chain reaction in anterior uveitis. American journal of ophthalmology. 2013 May:155(5):781-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.12.008. Epub 2013 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 23415597]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMastropasqua R, Di Carlo E, Sorrentino C, Mariotti C, da Cruz L. Intraocular Biopsy and ImmunoMolecular Pathology for "Unmasking" Intraocular Inflammatory Diseases. Journal of clinical medicine. 2019 Oct 19:8(10):. doi: 10.3390/jcm8101733. Epub 2019 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 31635036]

Kuo DE, Wei MM, Knickelbein JE, Armbrust KR, Yeung IYL, Lee AY, Chan CC, Sen HN. Logistic Regression Classification of Primary Vitreoretinal Lymphoma versus Uveitis by Interleukin 6 and Interleukin 10 Levels. Ophthalmology. 2020 Jul:127(7):956-962. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.01.042. Epub 2020 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 32197914]

Sudhir RR, Murthy PP, Tadepalli S, Murugan S, Padmanabhan P, Krishnamurthy A, Dickinson SL, Karthikeyan R, Kompella UB, Srinivas SP. Ocular Spot Fluorometer Equipped With a Lock-In Amplifier for Measurement of Aqueous Flare. Translational vision science & technology. 2018 Nov:7(6):32. doi: 10.1167/tvst.7.6.32. Epub 2018 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 30619652]

Yilmaz M, Guven Yilmaz S, Palamar M, Ates H, Yagci A. The effects of tropicamide and cyclopentolate hydrochloride on laser flare meter measurements in uveitis patients: a comparative study. International ophthalmology. 2021 Mar:41(3):853-857. doi: 10.1007/s10792-020-01639-3. Epub 2020 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 33200390]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcKay KM, Jacobs DS. In Vivo Confocal Microscopy of Keratic Precipitates in Uveitis. International ophthalmology clinics. 2019 Fall:59(4):95-103. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000290. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31569137]

Adl MA, LeHoang P, Bodaghi B. Use of fluorescein angiography in the diagnosis and management of uveitis. International ophthalmology clinics. 2012 Fall:52(4):1-12. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e3182662e49. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22954925]

Invernizzi A, Cozzi M, Staurenghi G. Optical coherence tomography and optical coherence tomography angiography in uveitis: A review. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2019 Apr:47(3):357-371. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13470. Epub 2019 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 30719788]

Elnahry AG, Ramsey DJ. Optical coherence tomography angiography imaging of the retinal microvasculature is unimpeded by macular xanthophyll pigment. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2020 Sep:48(7):1012-1014. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13824. Epub 2020 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 32643270]

Agrawal RV, Biswas J, Gunasekaran D. Indocyanine green angiography in posterior uveitis. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2013 Apr:61(4):148-59. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.112159. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23685486]

Korkmaz Ekren P, Mogulkoc N, Toreyin ZN, Egrilmez S, Veral A, Akalın T, Bacakoglu F. Conjunctival Biopsy as a First Choice to Confirm a Diagnosis of Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis, vasculitis, and diffuse lung diseases : official journal of WASOG. 2016 Oct 7:33(3):196-200 [PubMed PMID: 27758983]

Hershey JM, Pulido JS, Folberg R, Folk JC, Massicotte SJ. Non-caseating conjunctival granulomas in patients with multifocal choroiditis and panuveitis. Ophthalmology. 1994 Mar:101(3):596-601 [PubMed PMID: 8127581]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBui KM, Garcia-Gonzalez JM, Patel SS, Lin AY, Edward DP, Goldstein DA. Directed conjunctival biopsy and impact of histologic sectioning methodology on the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. Journal of ophthalmic inflammation and infection. 2014 Mar 18:4(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1869-5760-4-8. Epub 2014 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 24641867]

Martin DF, Chan CC, de Smet MD, Palestine AG, Davis JL, Whitcup SM, Burnier MN Jr, Nussenblatt RB. The role of chorioretinal biopsy in the management of posterior uveitis. Ophthalmology. 1993 May:100(5):705-14 [PubMed PMID: 8493014]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHosoda Y, Hayashi H, Kuriyama S. Posterior subtenon triamcinolone acetonide injection as a primary treatment in eyes with acute Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2015 Sep:99(9):1211-4. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2014-306244. Epub 2015 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 25792626]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBor'i A, Mahrous A, Al-Aswad MA, Al-Nashar HY, Nada WM, Wagih M, Awad AMB, El-Haig WM. Intravitreal Clindamycin and Dexamethasone Combined with Systemic Oral Antitoxoplasma Therapy versus Intravitreal Therapy Alone in the Management of Toxoplasma Retinochoroiditis: A Retrospective Study. Journal of ophthalmology. 2018:2018():4160837. doi: 10.1155/2018/4160837. Epub 2018 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 29619254]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKim M, Kim SA, Park W, Kim RY, Park YH. Intravitreal Dexamethasone Implant for Treatment of Sarcoidosis-Related Uveitis. Advances in therapy. 2019 Aug:36(8):2137-2146. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-00989-4. Epub 2019 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 31140122]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBienvenu AL, Aussedat M, Mathis T, Guillaud M, Leboucher G, Kodjikian L. Intravitreal Injections of Voriconazole for Candida Endophthalmitis: A Case Series. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2020 Apr 2:28(3):471-478. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2019.1571613. Epub 2019 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 30810429]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNguyen QD, Merrill PT, Clark WL, Banker AS, Fardeau C, Franco P, LeHoang P, Ohno S, Rathinam SR, Thurau S, Abraham A, Wilson L, Yang Y, Shams N, Sirolimus study Assessing double-masKed Uveitis tReAtment (SAKURA) Study Group. Intravitreal Sirolimus for Noninfectious Uveitis: A Phase III Sirolimus Study Assessing Double-masKed Uveitis TReAtment (SAKURA). Ophthalmology. 2016 Nov:123(11):2413-2423. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.07.029. Epub 2016 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 27692526]

Nguyen QD, Merrill PT, Sepah YJ, Ibrahim MA, Banker A, Leonardi A, Chernock M, Mudumba S, Do DV. Intravitreal Sirolimus for the Treatment of Noninfectious Uveitis: Evolution through Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Ophthalmology. 2018 Dec:125(12):1984-1993. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.06.015. Epub 2018 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 30060978]

Nche EN, Amer R. Lens-induced uveitis: an update. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2020 Jul:258(7):1359-1365. doi: 10.1007/s00417-019-04598-3. Epub 2020 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 31907641]

Du L, Kijlstra A, Yang P. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: Novel insights into pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2016 May:52():84-111. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2016.02.002. Epub 2016 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 26875727]

. A controlled trial of oral acyclovir for iridocyclitis caused by herpes simplex virus. The Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1996 Sep:114(9):1065-72 [PubMed PMID: 8790090]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOliver GF, Stathis RM, Furtado JM, Arantes TE, McCluskey PJ, Matthews JM, International Ocular Syphilis Study Group, Smith JR. Current ophthalmology practice patterns for syphilitic uveitis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Nov:103(11):1645-1649. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313207. Epub 2019 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 31021330]

Gupta V, Shoughy SS, Mahajan S, Khairallah M, Rosenbaum JT, Curi A, Tabbara KF. Clinics of ocular tuberculosis. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2015 Feb:23(1):14-24. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2014.986582. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25615807]

Riancho-Zarrabeitia L, Calvo-Río V, Blanco R, Mesquida M, Adan AM, Herreras JM, Aparicio Á, Peiteado-Lopez D, Cordero-Coma M, García Serrano JL, Ortego-Centeno N, Maíz O, Blanco A, Sánchez-Bursón J, González-Suárez S, Fonollosa A, Santos-Gómez M, González-Vela C, Loricera J, Pina T, González-Gay MA. Anti-TNF-α therapy in refractory uveitis associated with sarcoidosis: Multicenter study of 17 patients. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2015 Dec:45(3):361-8. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.05.010. Epub 2015 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 26092330]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHasegawa E, Takeda A, Yawata N, Sonoda KH. The effectiveness of adalimumab treatment for non-infectious uveitis. Immunological medicine. 2019 Jun:42(2):79-83. doi: 10.1080/25785826.2019.1642080. Epub 2019 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 31315546]

Ganesh SK, Mistry S. Phacoemulsification with Intraocular Lens Implantation in Pediatric Uveitis: A Retrospective Study. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2018:26(2):305-312. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2016.1206944. Epub 2016 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 27598822]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChiu H, Dang H, Cheung C, Khosla D, Arjmand P, Rabinovitch T, Derzko-Dzulynsky L. Ten-year retrospective review of outcomes following phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation in patients with pre-existing uveitis. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2017 Apr:52(2):175-180. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2016.10.007. Epub 2017 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 28457287]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiu X, Zhao C, Xu T, Gao F, Wen X, Wang M, Pei M, Zhang M. Visual Prognosis and Associated Factors of Phacoemulsification and Intraocular Lens Implantation in Different Uveitis Entities in Han Chinese. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2017 Jun:25(3):349-355. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2015.1125512. Epub 2016 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 26902289]

Hu J, Vu JT, Hong B, Gottlieb C. Uveitis and cystoid macular oedema secondary to topical prostaglandin analogue use in ocular hypertension and open angle glaucoma. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2020 Aug:104(8):1040-1044. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2019-315280. Epub 2020 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 32532763]

Horsley MB, Chen TC. The use of prostaglandin analogs in the uveitic patient. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2011 Jul-Sep:26(4-5):285-9. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2011.588650. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21958176]

Razeghinejad MR. The Effect of Latanaprost on Intraocular Inflammation and Macular Edema. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2019:27(2):181-188. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2017.1372485. Epub 2017 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 29028372]

Kwon HJ, Kong YXG, Tao LW, Lim LL, Martin KR, Green C, Ruddle J, Crowston JG. Surgical outcomes of trabeculectomy and glaucoma drainage implant for uveitic glaucoma and relationship with uveitis activity. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2017 Jul:45(5):472-480. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12916. Epub 2017 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 28134460]

Bettis DI, Morshedi RG, Chaya C, Goldsmith J, Crandall A, Zabriskie N. Trabeculectomy With Mitomycin C or Ahmed Valve Implantation in Eyes With Uveitic Glaucoma. Journal of glaucoma. 2015 Oct-Nov:24(8):591-9. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000195. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25393037]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee JW, Chan JCh, Qing L, Lai JS. Early Postoperative Results and Complications of using the EX-PRESS Shunt in uncontrolled Uveitic Glaucoma: A Case Series of Preliminary Results. Journal of current glaucoma practice. 2014 Jan-Apr:8(1):20-4. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10008-1156. Epub 2014 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 26997803]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSakata VM, Morita C, Lavezzo MM, Rodriguez EEC, Abdallah SF, Pimentel SLG, Hirata CE, Yamamoto JH. Outcomes of Intravitreal Bevacizumab in Choroidal Neovascularization in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease- A Prospective Study. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2021 Apr 3:29(3):572-578. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2019.1687731. Epub 2019 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 31746659]

Cervantes-Castañeda RA, Giuliari GP, Gallagher MJ, Yilmaz T, MacDonell RE, Quinones K, Foster CS. Intravitreal bevacizumab in refractory uveitic macular edema: one-year follow-up. European journal of ophthalmology. 2009 Jul-Aug:19(4):622-9 [PubMed PMID: 19551679]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKozak I, Shoughy SS, Stone DU. Intravitreal Antiangiogenic Therapy of Uveitic Macular Edema: A Review. Journal of ocular pharmacology and therapeutics : the official journal of the Association for Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2017 May:33(4):235-239. doi: 10.1089/jop.2016.0118. Epub 2017 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 28165851]

Talat L, Lightman S, Tomkins-Netzer O. Ischemic retinal vasculitis and its management. Journal of ophthalmology. 2014:2014():197675. doi: 10.1155/2014/197675. Epub 2014 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 24839552]

Miyao A, Ikeda T, Matsumoto Y, Uchida K, Machida T, Hongo M, Kinoshita S. Histopathological findings in proliferative membrane from a patient with sarcoid uveitis. Japanese journal of ophthalmology. 1999 May-Jun:43(3):209-12 [PubMed PMID: 10413255]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePark UC, Yu HG. Ocular Inflammation and Choroidal Thickness after Pars Plana Vitrectomy in Chronic Recurrent Stage of Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2021 Feb 17:29(2):388-395. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2019.1677918. Epub 2019 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 31671005]

Kanavi MR, Soheilian M. Confocal Scan Features of Keratic Precipitates in Granulomatous versus Nongranulomatous Uveitis. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2011 Oct:6(4):255-8 [PubMed PMID: 22454748]

Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, Rodríguez-García A, Foster CS. Pigment dispersion syndrome masquerading as acute anterior uveitis. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2011 Jun:19(3):158-66. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2011.557759. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21595531]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFeng L, Zhu J, Gao T, Li B, Yang Y. Uveal melanoma in the peripheral choroid masquerading as chronic uveitis. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 2014 Sep:91(9):e222-5. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000350. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25036546]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKiratli H, Mocan MC, İrkeç M. In vivo Confocal Microscopy in Differentiating Ipilimumab-Induced Anterior Uveitis from Metastatic Uveal Melanoma. Case reports in ophthalmology. 2016 Sep-Dec:7(3):126-131 [PubMed PMID: 27790127]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTakahashi T, Oda Y, Chiba T, Ogasawara M, Kamao T. Metastatic carcinoma of the iris and ciliary body simulating iridocyclitis. Ophthalmologica. Journal international d'ophtalmologie. International journal of ophthalmology. Zeitschrift fur Augenheilkunde. 1984:188(4):266-72 [PubMed PMID: 6539888]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSOLL DB, TURTZ AI. Retinoblastoma diagnosed as granulomatous uveitis. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1960 Apr:63():687-91 [PubMed PMID: 13832619]

Kanavi MR, Soheilian M, Bijanzadeh B, Peyman GA. Diagnostic vitrectomy (25-gauge) in a case with intraocular lymphoma masquerading as bilateral granulomatous panuveitis. European journal of ophthalmology. 2010 Jul-Aug:20(4):795-8 [PubMed PMID: 20099241]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoktas A, Goktas S. Bilateral acute depigmentation of the iris first misdiagnosed as acute iridocyclitis. International ophthalmology. 2011 Aug:31(4):337-9. doi: 10.1007/s10792-011-9452-x. Epub 2011 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 21633847]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHadda V, Pandey BD, Gupta R, Goel A. Azathioprine induced pancytopenia: a serious complication. Journal of postgraduate medicine. 2009 Apr-Jun:55(2):139-40. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.52849. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19550063]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBath RK, Brar NK, Forouhar FA, Wu GY. A review of methotrexate-associated hepatotoxicity. Journal of digestive diseases. 2014 Oct:15(10):517-24. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12184. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25139707]

Metushi I, Uetrecht J, Phillips E. Mechanism of isoniazid-induced hepatotoxicity: then and now. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2016 Jun:81(6):1030-6. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12885. Epub 2016 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 26773235]

Ben-Harari RR, Goodwin E, Casoy J. Adverse Event Profile of Pyrimethamine-Based Therapy in Toxoplasmosis: A Systematic Review. Drugs in R&D. 2017 Dec:17(4):523-544. doi: 10.1007/s40268-017-0206-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28879584]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChoi SY, Hwang JM. Optic neuropathy associated with ethambutol in Koreans. Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 1997 Dec:11(2):106-10 [PubMed PMID: 9510653]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAman R, Engelhard SB, Bajwa A, Patrie J, Reddy AK. Ocular hypertension and hypotony as determinates of outcomes in uveitis. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2015:9():2291-8. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S90636. Epub 2015 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 26672771]

Marchese A, Giuffrè C, Miserocchi E, Cicinelli MV, Bandello F, Modorati G. Severe Hypotony Maculopathy in Anterior Uveitis Associated with Hodgkin Lymphoma. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2021 Apr 3:29(3):460-464. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2019.1668952. Epub 2019 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 31647699]

Moorthy RS, Mermoud A, Baerveldt G, Minckler DS, Lee PP, Rao NA. Glaucoma associated with uveitis. Survey of ophthalmology. 1997 Mar-Apr:41(5):361-94 [PubMed PMID: 9163835]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDyer G, Rohl A, Shaikh S. Ocular Sarcoidosis Limited to Retinal Vascular Ischemia and Neovascularization. Cureus. 2016 Oct 21:8(10):e839 [PubMed PMID: 27928517]

Birnie DH, Nery PB, Ha AC, Beanlands RS. Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2016 Jul 26:68(4):411-21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.605. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27443438]

Zafar S, Mishra K, Sachdeva MM. SYPHILITIC OUTER RETINOPATHY: A MASQUERADING DIAGNOSIS REVEALED AFTER STEROID-INDUCED PROGRESSION TO PANUVEITIS. Retinal cases & brief reports. 2023 Jan 1:17(1):9-12. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000001106. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33323897]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHasanreisoglu M, Gulpinar Ikiz G, Aktas Z, Ozdek S. Intravitreal dexamethasone implant as an option for anti-inflammatory therapy of tuberculosis uveitis. International ophthalmology. 2019 Feb:39(2):485-490. doi: 10.1007/s10792-018-0831-4. Epub 2018 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 29380185]

Sahin O, Ziaei A. The role of methotrexate in resolving ocular inflammation after specific therapy for presumed latent syphilitic uveitis and presumed tuberculosis-related uveitis. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2014 Jul:34(7):1451-9. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000080. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24531737]

Agarwal A, Handa S, Aggarwal K, Sharma M, Singh R, Sharma A, Agrawal R, Sharma K, Gupta V. The Role of Dexamethasone Implant in the Management of Tubercular Uveitis. Ocular immunology and inflammation. 2018:26(6):884-892. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2017.1400074. Epub 2017 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 29190170]

Villalobos-Pérez A, Reyes-Guanes J, Muñoz-Ortiz J, Estévez-Florez MA, Ramos-Santodomingo M, Balaguera-Orjuela V, de-la-Torre A. Referral Process in Patients with Uveitis: A Challenge in the Health System. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2021:15():1-10. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S287766. Epub 2021 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 33442226]

Olivieri I, Accorinti M, Abicca I, Bisceglia P, Cimino L, Latanza L, Leccese P, Lubrano E, Marchesoni A, Miserocchi E, Neri P, Salvarani C, Scarpa R, D'Angelo S, CORE Study Group. Standardization of red flags for referral to rheumatologists and ophthalmologists in patients with rheumatic diseases and ocular involvement: a consensus statement. Rheumatology international. 2018 Sep:38(9):1727-1734. doi: 10.1007/s00296-018-4094-1. Epub 2018 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 29961101]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDick AD, Rosenbaum JT, Al-Dhibi HA, Belfort R Jr, Brézin AP, Chee SP, Davis JL, Ramanan AV, Sonoda KH, Carreño E, Nascimento H, Salah S, Salek S, Siak J, Steeples L, Fundamentals of Care for Uveitis International Consensus Group. Guidance on Noncorticosteroid Systemic Immunomodulatory Therapy in Noninfectious Uveitis: Fundamentals Of Care for UveitiS (FOCUS) Initiative. Ophthalmology. 2018 May:125(5):757-773. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.11.017. Epub 2018 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 29310963]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAgrawal R, Testi I, Bodaghi B, Barisani-Asenbauer T, McCluskey P, Agarwal A, Kempen JH, Gupta A, Smith JR, de Smet MD, Yuen YS, Mahajan S, Kon OM, Nguyen QD, Pavesio C, Gupta V, Collaborative Ocular Tuberculosis Study Consensus Group. Collaborative Ocular Tuberculosis Study Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Tubercular Uveitis-Report 2: Guidelines for Initiating Antitubercular Therapy in Anterior Uveitis, Intermediate Uveitis, Panuveitis, and Retinal Vasculitis. Ophthalmology. 2021 Feb:128(2):277-287. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.06.052. Epub 2020 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 32603726]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence