Introduction

Cephalometric analysis evaluates lateral skull radiographs obtained with a cephalostat to help determine the skeletal pattern and assess treatment difficulty. Cephalometric analysis is indicated when anteroposterior movement is planned but is not required for all orthodontic treatments. The use of cephalometric analysis is justified when the incisor position will be significantly modified.

The technique of cephalometric analysis has a rich history dating back to the late 1800s when radiographs were first employed to study the head and neck. In the 1930s, Holly Broadbent, a professor of orthodontics at the University of Michigan, analyzed the correlation between the teeth and the skull. This pioneering work involved measuring various angles and distances on the radiographic image, establishing the foundations of cephalometric analysis.[1] Researchers continued to build upon this work throughout the following decades, developing other methods, like the Wits analysis. In current clinical practice, cephalometric analysis is essential in orthodontics to help diagnose and correct various dental and skeletal anomalies.[2]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

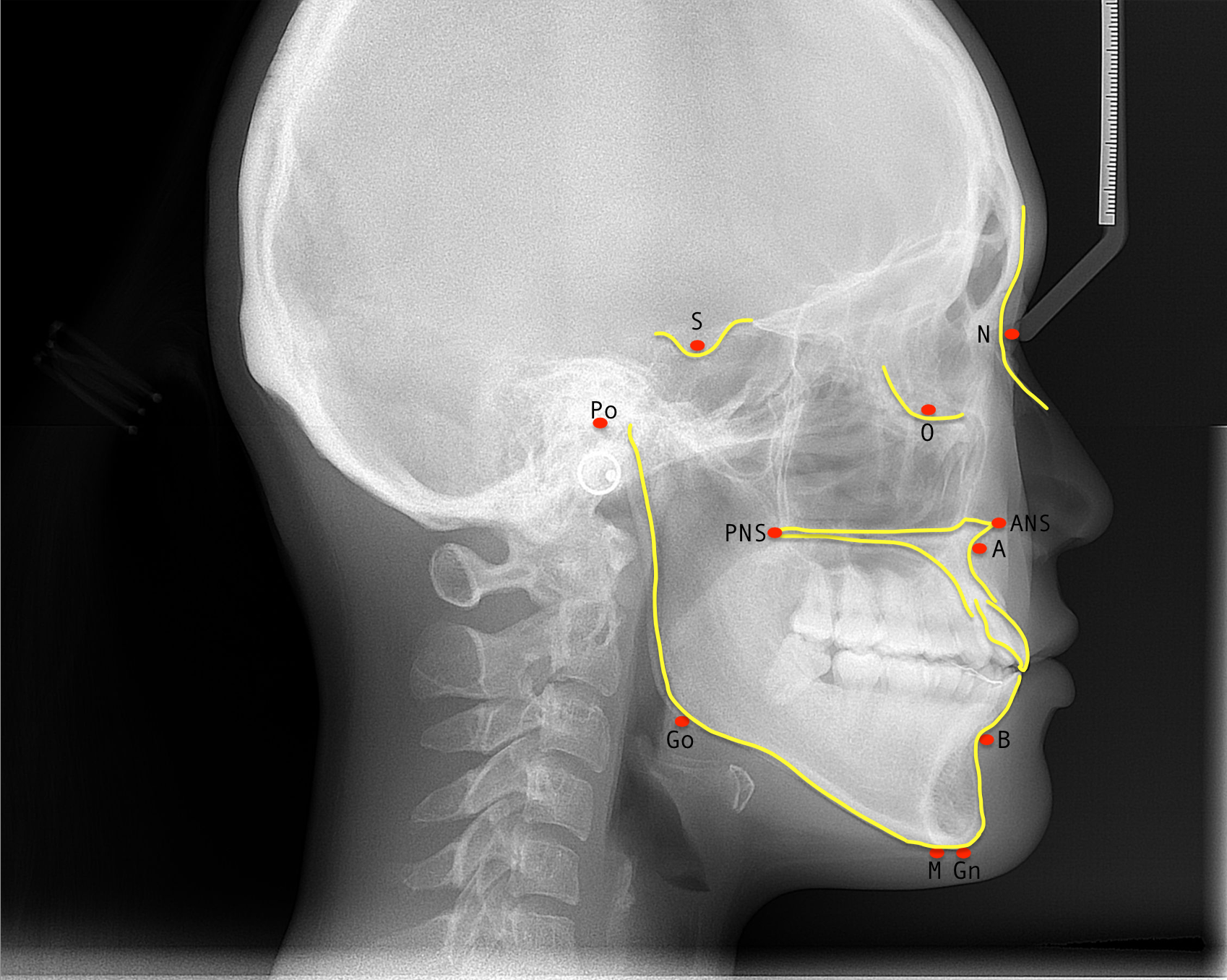

Cephalometric analysis evaluates the anteroposterior and vertical relationships of the mandible and maxilla with the cranial base and each other and the relationships of the upper and lower teeth to the mandibular and maxillary bones (see Image. Common Cephalometric Points). The analysis compares the patient-specific proportions and measurements of angles with average values for the population. These measurements can be manually traced or digitized. The results of cephalometric analysis are subject to errors in projection and measures and are operator-dependent. Therefore, the cephalometric values of a single patient must be interpreted within the clinical context; deviations from average values may be compensated elsewhere in the face or skull.

The following tables describe commonly used cephalometric points (Table 1) and planes (Table 2).[2][3]

Table 1. Cephalometric Points

| Cephalometric Point | Anatomical Description |

| Sella (S) | The midpoint of the sella turcica |

| Nasion (N) | The most anterior point of the frontonasal suture or the deepest point of the intersection of the frontal and nasal bones |

| Orbitale (Or) | The most anteroinferior point on the infraorbital margin using the average of the right and left shadows |

| Porion (Po) | The most superior and external point of the bony external auditory meatus or the level of the superior border of the mandibular condyle |

|

Anterior Nasal Spine (ANS) |

The tip of the anterior nasal spine |

| Posterior Nasal Spine (PNS) | The tip of the posterior nasal spine |

| A-point (A) | The most posterior point of the concavity of the maxilla between the anterior nasal spine and the maxillary alveolar process |

| B-point (B) | The most posterior point of the concavity of the mandible between the pogonion and the crest of the mandibular alveolar process |

| Menton (Me) | The most inferior point on the mandibular symphysis in the midline |

| Pogonion (Pog) | The most anterior point on the contour of the bony chin |

| Gnathion (Gn) | The lowest and most forward point on the chin outline |

| Condylion (Cd) | The lowest and most superoposterior point on the curvature of the average of the right and left outlines of the condylar heads |

Table 2. Cephalometric Planes

| Cephalometric Plane | Anatomical Description |

| Sella-Nasion (SN) plane | A horizontal plane passing through the sella turcica and nasion; a reference for measuring the anteroposterior relationship between the jaws and facial structures |

| Frankfort plane | A horizontal plane formed by a line that joins the porion and orbitale; a reference for assessing the vertical relationship between the jaws and facial structures |

| Mandibular plane | A line through the inferior border of the mandible joining the gonion and menton; a reference for evaluating the vertical position of the mandible |

| Maxillary plane | A line joining the anterior and posterior nasal spines; a reference for assessing the angulation and position of the maxilla |

| Occlusal plane | A horizontal plane touching the incisal edges of the maxillary and mandibular incisors and the tips of the occlusal surfaces of the posterior teeth |

| Camper's plane | A horizontal plane passing through the inferior margin of the nasal ala and the superior margin of the tragus; a reference for evaluating the inclination of the upper lip and the position of the incisors |

Indications

Cephalometric analysis aids in diagnosing dental and skeletal malocclusion, planning corrective treatment, and evaluating treatment and growth changes.

Technique or Treatment

Standardized Lateral Cephalometric Radiographs

Lateral skull radiographs provide a two-dimensional representation of the head and neck and measure the sagittal and vertical dimensions of the skull. The sagittal measurements study position and inclination of the maxilla and mandible, while vertical measurements evaluate the height of the facial structures and the relationship between the jaw.[4] Posteroanterior radiographs, on the other hand, are taken from the front of the head and measure both transverse and vertical dimensions. They provide information about the width of the face and the relationship between the jaws in the transverse plane.[5] However, in clinical practice, cephalometric analysis is mainly based on lateral radiographs since posteroanterior projections are much harder to interpret.

A standardized technique is used for obtaining radiographs to allow comparison over time and between patients. The quality of the image relies heavily on the position of the patient. The patient must be positioned so the Frankfort plane is horizontal, the ear rests are placed in the external auditory meatuses, the nasion on the bridge of the nose, and the teeth are in centric occlusion.[6] The radiographic source is at a fixed distance of 5 ft (150 to 180 cm) from the patient's mid-sagittal plane, and the film to midsagittal plane distance is 30 cm.[6] A calibrated steel ruler is recorded on each image. This setup ensures that precise measurements are documented.

Cephalometric Tracing

Lateral cephalometric radiographs are traditionally traced manually. First, a tracing acetate has to be attached to the film. After identifying the anatomical landmarks, they are drawn on the tracing acetate using a sharp 4H pencil. These points are joined, forming lines and angles, and the measurements obtained are recorded and interpreted.

Digital tracing with specialized software is also possible, facilitating the process of cephalometric analysis. The software automatically identifies the anatomical landmarks on the radiographs and calculates measurements. It also provides standards for comparison based on ethnicity, sex, and age and allows soft tissue alteration, growth, and surgical prediction.[7] Both manual and digital tracing techniques are appropriate for cephalometric analysis.

Clinical Significance

Interpretation of Cephalometric Analysis Results

Average angular measurements and proportions have been established for the general population. However, these values are general guides, as standard measures may vary by age, sex, and ethnicity.[8] A thorough orthodontic assessment must consider the unique skeletal and dental characteristics in combination with the cephalometric findings.

Anteroposterior Evaluation

SNA Angle

The SNA angle evaluates the anteroposterior position of the maxilla to the anterior cranial base.[9] The SNA angle is formed by joining the sella, nasion, and A point. The average SNA angle is 81 +/- 3 degrees. A patient with an SNA angle of 82 degrees presents a well-positioned maxilla concerning the cranial base.[10]

An increased SNA angle means that the maxilla is in a protrusive relationship to the cranial base compared to the average.[3] A decreased SNA angle means the opposite; the maxilla is in a retruded position to the cranial base compared to the norm.[3]

SNB Angle

The SNB angle evaluates the anteroposterior position of the mandible to the anterior cranial base.[9] The SNB angle is formed by joining the sella to nasion to B point. The average SNB angle is 78 +/- 3 degrees.[10] An increased SNB angle means the mandible is protruded to the cranial base compared to the average.[11] A decreased SNB angle means the mandible is retruded to the cranial base compared to the average.[11]

ANB Angle

The ANB angle measures the anteroposterior relationship between the maxilla and the mandible.[12] The ANB angle is the difference between SNA (sella-nasion to A point) and SNB (sella-nasion to B point). It is obtained using the equation: ANB = SNA - SNB.[10]

The average ANB angle for a class I skeletal pattern is 2 degrees. An ANB angle greater than 4 degrees indicates a class II skeletal pattern and an angle less than 2 degrees indicates a class III skeletal pattern.[13] However, the ANB angle varies according to the position of the nasion and the prominence of the lower face. When the ANB angle is abnormally increased or decreased, a different method, such as the Wits analysis, must be implemented.

Wits Analysis

The Wits analysis is an alternative method to evaluate the anteroposterior skeletal pattern, which does not rely on the cranial base. This method involves drawing perpendicular lines from points A and B to the occlusal plane – the line joining the tips of the cusps of posterior teeth.[14] The point of contact between the perpendiculars from the A and B points and the occlusal plane form points AO and BO.[14] The distance between AO to BO is measured, giving the following measures for class I skeletal pattern: BO 1 mm (+/- 1.9 mm) anterior to AO in males, and BO equals AO (+/- 1.77 mm) in females.[14]

Vertical Evaluation

The maxillary-mandibular plane angle (MMPA) evaluates the vertical relationship between the maxilla and mandible. The MMPA is formed by projecting lines from the mandibular and maxillary planes until they touch posteriorly. The average value for the MMPA is 27 +/- 4 degrees. An average MMPA value correlates with a well-proportioned lower face and a normal overbite. An increased MMPA value relates to a long lower face and an open bite, whereas a decreased MMPA value relates to a shorter lower face and a closed bite.[15]

Incisor Position: Angular Evaluation

The angular measurement of the maxilla is determined by measuring from the incisor to Nasion-A. The angular measures of the mandible are calculated from the incisor to Nasion-B. These values indicate tooth inclination: proclined teeth are tipped forwards, retroclined teeth are tilted backward, or normally inclined.[8] The normal incisor to nasion-A angle is 22 degrees, and the normal incisor to nasion-B angle is 25 degrees. An increased incisor to nasion-A or B angle indicates that the incisor is proclined, whereas a decreased angle suggests that the incisor is retroclined.[3]

The position of mandibular incisors is further evaluated by the angle formed by the intersection of the long axis of the tooth with the mandibular plane, which runs from gonion to gnathion.[10] The normal mandibular incisor to mandibular plane angle (Go-Gn) is 87 degrees. An increased mandibular incisor to mandibular plane angle indicates the incisors are proclined, and on the contrary, a decreased value indicates the incisors are retroclined.[8]

Incisor Position: Linear Evaluation

The linear measurement of the maxilla is determined by measuring from the maxillary incisor to Nasion-A, and the linear measurement of the mandible is measured from the incisor to Nasion-B. These measurements describe how the tooth relates to its supporting basal bone, be it normal, procumbent, where the tooth is ahead of its supporting bone, or recumbent, where the tooth is behind its supporting bone.[10]

The average value for both incisor to nasion-A and incisor to nasion-B is 4 mm. An increased incisor to nasion-A or -B value indicates that the incisor is procumbent, and a decreased value suggests that the incisor is recumbent.[16]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cephalometric analysis allows for the diagnosis and treatment of malocclusion, which requires an interprofessional team of dental health professionals, including but not limited to general dentists, orthodontists, and oral surgeons. Cephalometric analysis sheds light on the extent of skeletal and dental misalignments and possible causative factors. If a malocclusion is too severe to be treated by an orthodontist alone, a referral can be made for the patient to seek treatment by an oral surgeon, who can work with the orthodontist to correct the misaligned jaw utilizing orthognathic surgery, further emphasizing the need for an interprofessional approach to the diagnosis and management of complex orthodontic malocclusions. Meticulous planning and discussion with other professionals involved in managing orthodontic treatment are highly recommended to allow for successful patient outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jha MS. Cephalometric Evaluation Based on Steiner's Analysis on Adults of Bihar. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences. 2021 Nov:13(Suppl 2):S1360-S1364. doi: 10.4103/jpbs.jpbs_172_21. Epub 2021 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 35017989]

Hans MG, Palomo JM, Valiathan M. History of imaging in orthodontics from Broadbent to cone-beam computed tomography. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2015 Dec:148(6):914-21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2015.09.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26672697]

Bergman RT. Cephalometric soft tissue facial analysis. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 1999 Oct:116(4):373-89 [PubMed PMID: 10511665]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAldrees AM. Lateral cephalometric norms for Saudi adults: A meta-analysis. The Saudi dental journal. 2011 Jan:23(1):3-7. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2010.09.002. Epub 2010 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 24151411]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDinesh A, Mutalik S, Feldman J, Tadinada A. Value-addition of lateral cephalometric radiographs in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. The Angle orthodontist. 2020 Sep 1:90(5):665-671. doi: 10.2319/062319-425.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33378477]

Gupta S, Tandon P, Singh GP, Shastri D. Comparative assessment of cephalometric with its analogous photographic variables. National journal of maxillofacial surgery. 2022 Jan-Apr:13(1):99-107. doi: 10.4103/njms.NJMS_267_20. Epub 2022 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 35911811]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTsorovas G, Karsten AL. A comparison of hand-tracing and cephalometric analysis computer programs with and without advanced features--accuracy and time demands. European journal of orthodontics. 2010 Dec:32(6):721-8. doi: 10.1093/ejo/cjq009. Epub 2010 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 20554891]

Scheideman GB, Bell WH, Legan HL, Finn RA, Reisch JS. Cephalometric analysis of dentofacial normals. American journal of orthodontics. 1980 Oct:78(4):404-20 [PubMed PMID: 6933849]

Brevi B, Di Blasio A, Di Blasio C, Piazza F, D'Ascanio L, Sesenna E. Which cephalometric analysis for maxillo-mandibular surgery in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome? Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2015 Oct:35(5):332-7. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-415. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26824915]

Tenti FV. Cephalometric analysis as a tool for treatment planning and evaluation. European journal of orthodontics. 1981:3(4):241-5 [PubMed PMID: 6945994]

Schwendicke F, Chaurasia A, Arsiwala L, Lee JH, Elhennawy K, Jost-Brinkmann PG, Demarco F, Krois J. Deep learning for cephalometric landmark detection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical oral investigations. 2021 Jul:25(7):4299-4309. doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-03990-w. Epub 2021 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 34046742]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDi Blasio A, Di Blasio C, Pedrazzi G, Cassi D, Magnifico M, Manfredi E, Gandolfini M. Combined photographic and ultrasonographic measurement of the ANB angle: a pilot study. Oral radiology. 2017:33(3):212-218. doi: 10.1007/s11282-017-0275-y. Epub 2017 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 28890606]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePlaza SP, Reimpell A, Silva J, Montoya D. Relationship between skeletal Class II and Class III malocclusions with vertical skeletal pattern. Dental press journal of orthodontics. 2019 Sep 5:24(4):63-72. doi: 10.1590/2177-6709.24.4.063-072.oar. Epub 2019 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 31508708]

Jacobson A. The "Wits" appraisal of jaw disharmony. American journal of orthodontics. 1975 Feb:67(2):125-38 [PubMed PMID: 1054214]

Kotuła J, Kuc AE, Lis J, Kawala B, Sarul M. New Sagittal and Vertical Cephalometric Analysis Methods: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Jul 15:12(7):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12071723. Epub 2022 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 35885628]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLentini-Oliveira DA, Carvalho FR, Rodrigues CG, Ye Q, Prado LB, Prado GF, Hu R. Orthodontic and orthopaedic treatment for anterior open bite in children. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Sep 24:(9):CD005515. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005515.pub3. Epub 2014 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 25247473]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence