Extraocular Muscle Management With Orbital and Globe Trauma

Extraocular Muscle Management With Orbital and Globe Trauma

Introduction

Extraocular muscle (EOM) management from ocular, orbital, and cranial trauma can be varied and complex. In the known ocular or orbital trauma setting, elucidating the mechanism, type, and severity of the injury helps triage critical components of the physical exam. Recognition and treatment of life-threatening injuries following Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) principles hold precedence over all others. These injuries are more commonly encountered when the body has sustained high-velocity forces, such as motor vehicle accidents or firearm assault.

Addressing EOM management in trauma can be conceptualized in two ways: one where there is damage to the EOMs and one where there is not. Direct EOM involvement can range from mild: minimal displacement from adjacent soft tissue edema or hemorrhage; to moderate: contusion of the EOM itself; to severe: disinsertion, laceration, or incarceration of the EOM from the traumatic blow or by an orbital fracture. Indirectly, EOM motility may be impaired from cranial nerve palsy or supranuclear injury associated with head and neck trauma. Contrarily, the EOMs may not be damaged but may need to be iatrogenically detached from the globe to explore and repair open globe injuries.

The presence or suspicion of an open globe injury and mechanical causes of strabismus or neurologic involvement guides the planning and timing of surgery. The goal of EOM management during acute ocular or orbital surgery is to limit the amount of fibrosis that could occur and result in strabismus.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The anatomy of EOMs and their innervation is complex (Table 1). Damage to the cranial nerves at the level of the orbital apex, cavernous sinus, nuclei and fascicles of the brainstem, and supranuclear structures can cause paretic strabismus. This article is mainly concerned with EOM management distal to the orbital apex encountered during orbital and ocular trauma.

| EOM | Primary Action (of the globe, unless otherwise specified) | Secondary Action | Tertiary Action | Innervation |

| Medial rectus | Adduction | none | none | Inferior branch of the oculomotor nerve (CN III) |

| Lateral rectus | Abduction | none | none | Abducens nerve (CN VI) |

| Inferior rectus | Depression | Excyclotorsion | Adduction | Inferior branch of CN III |

| Superior rectus | Elevation | Incyclotorsion | Adduction | Superior branch of CN III |

| Inferior oblique | Excyclotorsion | Elevation | Abduction | Inferior branch of CN III |

| Superior oblique | Incyclotorsion | Depression | Abduction | Trochlear nerve (CN IV) |

| Levator palpebrae superioris | Upper eyelid elevation and retraction | none | none | Superior branch of CN III |

Table 1. The anatomy, actions, and innervation of EOMs.

The EOMs of the eye include the medial, inferior, lateral, and superior rectus, the superior and inferior oblique, and the levator palpebrae superioris (LPS). The rectus muscles originate from a fibrous ring termed the annulus of Zinn within the orbital apex. They insert onto the globe near the globe's equator at varying distances from the limbus: the medial rectus inserts the closest to the limbus, and the inferior rectus, lateral rectus, and superior rectus muscles each insert progressively further away, yielding an imaginary coil termed the spiral of Tillaux.[1]

The sclera is thinnest just posterior to the insertion of the rectus muscles (averaging about 0.3 mm in thickness), providing a potential site of rupture during globe trauma.[2] Notwithstanding breaks from the initial injury, sutures passing too deeply at or posterior to the rectus insertion site are at risk for scleral perforation and precipitating retinal breaks. Insertion distances vary among individuals, but conventionally taught measurements for the medial, inferior, lateral, and superior rectus muscles from the limbus are 5.5 mm, 6.5 mm, 6.9 mm, and 7.7 mm, respectively.[3] Patients with congenital fibrosis of extraocular muscles may have anomalously inserted tendons, thin tendons, or increased muscle tension.[4]

Accessory extraocular muscles or fibrotic structures have been described and may also be encountered during eyelid or orbital procedures.[5][6][7] Knowing this and the relationship of EOM globe insertion provides surgeons with an anatomical roadmap for globe exploration if an open wound is suspected but not obvious on the initial exam.

The EOMs are attached to check ligaments within an intermuscular membrane. This fibroelastic pulley system stabilizes the EOM bellies in space, preventing deep retraction of the muscle should it be disinserted or lacerated anteriorly, and may preserve muscle function on initial examination.[8] The Tenon capsule is an orbital fascia that envelopes the globe and anterior portion of the EOMs, forming a sleeve within which the eye can move. It fuses anteriorly with the intermuscular septum about 2 mm posterior to the limbus and posteriorly to the optic nerve sheath. These connections are advantageous for globe and strabismus surgeons if a muscle is "lost." The lateral rectus is connected to the inferior oblique muscle by a frenulum of the intermuscular septum. The superior rectus is loosely attached to the LPS and connected to the superior oblique by a frenulum of the intermuscular septum. The inferior rectus is attached to the lower eyelid retractors, the capsulopalpebral fascia, and the inferior tarsal muscle. Therefore, in traumatic cases where the lateral, superior, and inferior recti muscles are transected or must be detached for scleral exploration, these muscles should be isolated from their connective attachments so as not to advance or resect adjacent muscles unintentionally. The medial rectus is the only rectus muscle that does not have an oblique muscle running tangentially to it. Therefore there is no point of reference for finding the muscle if it is lost or slipped. It has been postulated that mechanisms of EOM flap tear injuries result from shearing forces created between the globe, orbital connective tissue, and bony orbit during high-velocity injuries.[9] Increased tension finally completes separation at the weakest point, usually at the EOM's tendinous portion or globe insertion. Further posterior EOM lacerations can make retrieval of the EOMs more challenging.

The oblique muscles course inferior to their corresponding rectus muscles and insert laterally onto the globe. The superior oblique muscle arises from the periosteum of the sphenoid bone body, but its functional origin is the trochlea. The trochlea acts as a pulley for the superior oblique and is situated on the superomedial aspect of the frontal bone, rendering it prone to trauma from penetrating hook injuries in the medial canthus.[10] The inferior oblique originates from the orbital portion of the maxillary bone, crosses the inferior rectus laterally, and inserts over the macula. Incarceration of the inferior oblique muscle or its branch of the oculomotor nerve (CN III) can occur with "trapdoor" fractures.[11] Additionally, the lateral inferior oblique runs with pupillomotor preganglionic parasympathetic nerves. Damage here can result clinically in a dilated pupil. Intraoperative considerations, such as a broad arc of contact with the globe and the possibility of the inferior oblique having more than one muscle belly, are likewise important.[12][13]

EOM entrapment or flap tears may follow orbital fractures, which comprise the most common cause of traumatic strabismus.[14] The resultant strabismus depends on the fracture location and extent of EOM involvement. The orbit is pyramidally shaped with the apex posteriorly and the base anteriorly. Seven bones form its boundaries (Table 2). Frontal force to the orbit or globe first impacts the orbital rim but can be transmitted posteriorly before buckling downwards. The orbital floor and medial wall are commonly affected, resulting in a blowout fracture. This type of injury usually results in a comminuted fracture pattern in adults.[15]

Bony fragments can impinge surrounding EOMs, commonly the inferior rectus, inferior oblique, and medial rectus, and less commonly, the superior oblique.[16] The bones are more elastic in pediatric patients, so upon initial blow, the bone bends, then entraps orbital tissue and muscle before closing back.[17] This fracture pattern has been described as a "trapdoor" because the fracture, which is linear and minimally displaced, opens transiently before rebounding back into place. Roof and lateral wall fractures are less common, and EOM entrapment is rare. In adult patients, the frontal sinus diffuses traumatic blunt force and prevents the extension of a fracture along the orbital roof. In pediatric patients, the frontal sinus is not yet fully pneumatized, and the ratio of the cranial vault to the midface is greater than in adults, so the frontal impact is more likely.[18] Regarding lateral wall fractures, isolated fracture through the greater wing of the sphenoid is rare. However, its articulation with the zygomatic bone, the sphenozygomatic suture, is prominent and susceptible to external trauma.[19][20]

| Orbital Wall | Bones Comprised Of |

| Inferior (floor) | zygomatic bone, maxilla bone, palatine bone |

| Superior (roof) | frontal bone, a lesser portion of the sphenoid bone |

| Medial | a lesser portion of the sphenoid bone, nasal bone, ethmoid bone, lacrimal bone |

| Lateral | the greater portion of the sphenoid bone, zygomatic bone |

Table 2. The bony walls of the orbit.

Though it does not insert onto the globe, the LPS is also considered an extraocular muscle. It indirectly facilitates eye movements by elevating and retracting the upper eyelid, allowing an unencumbered upward gaze. The LPS and the superior oblique originate from the lesser wing and body of the sphenoid bone, respectively. As it courses more anteriorly, the LPS encounters a superior transverse ligament, eponymously coined Whitnall's ligament, which pivots the path of the LPS from anterior-posterior to superior-inferior.[21] It widens and splits into two aponeurotic fibers: the deep fibers insert on the anterior surface of the superior tarsus; the superficial fibers, on the skin of the upper eyelid, after piercing the orbicularis oculi. The latter creates the eyelid margin.

The location of eyelid trauma to the eyelid margin can help surgeons distinguish whether or not the LPS or the deeper superior tarsal muscle (Muller's muscle) were injured, either indirectly from tissue edema, hemorrhage, or directly from penetrating eyelid injury. In the upper eyelid, the lower 5 mm has 4 layers (from superficial to deep): skin, orbicularis, tarsus, and conjunctiva; the middle 5mm contains the skin, orbicularis, LPS aponeurosis, tarsus, and conjunctiva; and above 10 mm, the eyelid contains the skin, orbicularis, septum, preaponeurotic fat, LPS aponeurosis, Muller's muscle, and conjunctiva.

Indications

Examination suggestive of globe perforation or intraocular (and sometimes intraorbital) foreign body (IOFB) usually requires immediate surgical exploration and repair by an ophthalmologist (or orbital surgeon).[22] Signs of an open globe injury may be obvious, such as direct visualization of the open wound or exposed uveal tissue, or more occult, such as conjunctival hemorrhage. With the latter, the wound may be underneath a rectus muscle. In these cases, the EOMs are explored at the time of globe repair and, if needed, detached then reattached to close the open wound. Other reasons for emergent exploration include "trapdoor" orbital fractures or clinical signs of muscle entrapment.[23]

In addition to the globe and orbital trauma, head trauma, including injury to the cranial nerve nucleus or fascicles (or both), subarachnoid space, cavernous sinus, and orbital apex, can cause immediate or delayed-onset strabismus.[24][25] Patient symptomology can range from subtle to dramatic, presenting unique challenges to the examiner. In the awake, alert patient, diplopia and gaze disturbance direct the examiner to test for limitations in EOM versions (binocular eye movement) or ductions (monocular eye movement).

Forced duction tests can further elucidate true restriction from entrapment or pseudo-restriction from surrounding edema. Forced ductions are beneficial when the patient can not participate in the subjective exam. Eye movement may stimulate the oculocardiac reflex, an arc whose afferent limb begins with stretch receptors via the ciliary ganglion and ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve. The efferent limb is mediated by the motor nucleus of the vagus nerve, causing bradycardia, pain, and nausea. The clinical history and exam are essential in management because not every orbital fracture warrants immediate, if any, repair. Oftentimes, waiting for the swelling to subside and watching for improvement in the patient's diplopia and ocular deviation, enophthalmos, and EOM motility may improve outcomes. The ideal watch and wait interval allows for the resolution of edema and avoids excessive scarring. The length of this period of observation varies among oculoplastic surgeons, but two weeks is often considered a good benchmark.[26]

Positively forced ductions and the presence of an oculocardiac reflex are signs of muscle entrapment and warrant immediate surgical exploration and repair. While computed tomography (CT) imaging is both helpful and used in concert with the clinical presentation and operative planning, EOM entrapment remains a clinical diagnosis. Without immediate repair, the entrapped muscle(s) is(are) at risk of atrophy or fibrosis from decreased arterial supply and can cause strabismus. The incidence of traumatic strabismus due to an EOM or cranial nerve (CN) palsy in orbital blow-out fractures is 17.5% in adults and about 10% in pediatric patients.[27][28] Forced duction testing is particularly useful when the etiology of strabismus, restrictive or paretic, is in question; in heavily sedated, medically uncooperative patients; and intraoperatively, before and after fracture reduction and implant placement.

The repair of direct EOM injury depends on the severity and extent of the injury. For example, muscle contusion or hemorrhage may be observed, while lacerated or disinserted EOMs may be repaired as early as possible to limit scarring.

Clinical signs suggestive of EOM entrapment (muscle involved):

- Dilated pupil (inferior oblique--damage to pupillomotor preganglionic parasympathetic nerves)

- Oculocardiac reflex with EOM versions or ductions (medial or inferior rectus)[29][30]

- Positively forced ductions (can occur with any EOM)

- Strabismus in primary or cardinal gazes (can occur with any EOM)

- Increased intraocular pressure (IOP) in upgaze compared to IOP in primary gaze (inferior rectus entrapment)

Patient symptoms suggestive of EOM entrapment or involvement:

- Diplopia and gaze disturbance

- Nausea, vomiting, pain, lightheadedness, increased vagal tone, especially in the direct muscle's primary action

- Younger age

- Asymptomatic*

*Of note, clinical exam findings could be absent, as is the case in white-eyed blowout fractures.

Certain history should elicit high suspicion for EOM involvement, including:

- Blunt head or facial trauma (motor vehicle accidents, firearm assault, physical assault, sports-related injury, falls)

- Penetrating injury to the globe, eyelid, or orbit (sharp, linear objects, hook objects)

Contraindications

Ophthalmic assessment treatment should not preclude life-threatening interventions.

If a metallic intraocular or intraorbital foreign body is suspected, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is contraindicated as the risk of dislodging the foreign body can damage surrounding structures.

Additionally, there are important considerations when evaluating EOM motility in patients with open globe injuries. If the wound is posterior to the limbus (Zone 2 or 3 injuries), the examiner may limit EOM assessment or any eye movement before primary repair. While this is not an absolute contraindication, doing so may risk expulsion of intraocular contents. Pre-operatively, a retrobulbar block is contraindicated in the presence of an open globe.

Equipment

Since ocular and orbital injuries can often occur in tandem with other head, neck, and bodily injuries, CT scans of the head, neck, and abdomen are generally ordered to evaluate for life-threatening injuries. Once those injuries have been addressed and managed, a complete ophthalmic exam can be performed. A comprehensive, 8-part ophthalmic exam is performed by an ophthalmologist or ophthalmologist-in-training. However, if an open globe is suspected, the single most important action nursing and emergency room staff can perform is to place a rigid shield over the affected eye. Signs of a ruptured globe, such as exposed uveal tissue, can halt a comprehensive ophthalmic exam until the primary repair is performed to prevent further damage and loss of vision.

Dedicated orbital or facial CT scans with 1-3 mm slice thickness help assess the bony orbit and extent of EOM and surrounding tissue injury. MRI, particularly dynamic (multi-positional) scanning, which has the patient looking in different gazes, provides detailed information of the entire length, contractility, and location relative to other orbital structures. Retained ferromagnetic (metallic) foreign bodies MUST be excluded before MRI. In the emergency setting, CT is more readily available than MRI.

Surgical trays for consideration:

- Globe exploration tray (if open globe or open globe suspect)

- IOFB removal tray (if IOFB is suspected based on history or imaging)

- Orbital tray (if orbital fracture)

- Strabismus tray (to isolate extraocular muscles)

While the type of surgical tray will vary depending on other orbital or ocular trauma, general instrumentation and supply for EOM management include:

- 0.12 mm, 0.3 mm, or 0.5 mm non-locking Castroviejo forceps

- 0.5 mm locking Stern-Castroviejo forceps

- Blunt Westcott scissors

- Eyelid speculum

- Curved needle holder

- Caliper

- Muscle hooks (Jameson, Green, Von Graefe, Stevens, Wright)*

- 4-0 silk suture (for traction)

- 5-0 or 6-0 absorbable polyglactin suture, double-armed with spatulated needles**

- 6-0 plain gut or 8-0 polyglactin suture (for conjunctival closure)

*When isolating muscles, having a variety of strabismus muscle hooks, ranging in size from larger muscle hooks with bulbous tips (such as a Jameson muscle hook) or flattened tips (like the Green and Von Graefe hooks) to smaller, curved tenotomy hooks (such as the Stevens hook), available can be helpful. Additional muscle hooks with a specialized groove to protect the sclera during muscle imbrication are also available (Wright hook).

**When detaching EOMs, a double-armed spatulated needle (typically 6-0 polyglactin suture) is useful. The double-armed nature facilitates easy reattachment to the globe. In addition, the spatulated needle has a flat top and bottom, which reduces the risk of inadvertent scleral perforation, especially when passing posterior to the rectus muscle previous insertion where it is thinnest.

Personnel

Before surgery, the patient has typically been evaluated by an emergency room or trauma provider to stabilize other injuries, if present. Intraoperative personnel includes the opthalmologist, orbital surgeon (an ophthalmologist trained in oculoplastic and orbital surgery, an otolaryngologist, or an oral and maxillofacial surgeon), first (and possibly, second) surgical assistant, anesthesia provider, operating room nurse, and surgical technician.

Preparation

Elucidating a history of chronically decreased vision, such as a history of amblyopia, cataracts, advanced glaucoma, or retinal pathology, can trick the examiner into thinking the patient has eye misalignment from trauma. However, this may be due to a sensory visual deprivation that results in sensory esotropia (more common in younger children) or sensory exotropia (more common in older children and adults). Other important clinical histories include previous head and neck trauma, vascular disease, or aneurysmal disease that resulted in a cranial nerve deficit that can also blur the etiology of diplopia and strabismus. In all of these groups of patients, the forced duction testing will be negative.

Important parts of the ophthalmic exam, such as visual acuity and EOM motility assessment, can be limited if the patient is sedated or uncooperative. Therefore, performing as much of the other parts of the ophthalmic exam as possible, forced duction testing, and CT imaging are critical.

Appropriate antibiotics should be given preoperatively to reduce the risk of infection. In the case of open globe injury, a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone is given pre-and post-operatively to prevent endophthalmitis. If Pseudomonas aeruginosa or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection are suspected, fortified topical antibiotics, such as fortified cefazolin or vancomycin and fortified tobramycin are recommended. Suspected fungal infections should be treated accordingly with antifungals. Intravitreal antibiotic injections are considered in eyes with heavy soil contamination, retinal periphlebitis, vitreous inflammation, hypopyon, or IOFB.[31]

Antibiotic prophylaxis in orbital surgery to prevent surgical site infections should be given pre- or intra-operatively.[32] Coordination between trauma teams and specialists is paramount to reduce overmedication and antibiotic resistance.

General anesthesia is the preferred anesthetic method for open globe and orbital fracture repair because it allows appropriate anesthesia and akinesia to perform safe microsurgery.

Technique or Treatment

Management of EOMs During Globe Repair

EOMs should be isolated and the sclera posterior to their insertion carefully examined for globe ruptures. During surgery, the surgeons must have excellent exposure, appropriate magnification, and adequate illumination. Surgical loupes or a zoom operating microscope are employed depending on the level of magnification and number of assistants during surgery (at least one). The surgical field is illuminated directly by the light microscope or by a separate headlamp.

If the surgeon is unfamiliar with the circulating operating room nurse, the surgeon should prepare the eye and surrounding area for surgery to avoid placing unnecessary pressure on the globe. An eyelid speculum that places minimal pressure on the globe, such as a Schott lid speculum or loose Jaffe speculum, is also positioned by the surgeon.

A 360-degree conjunctival peritomy is created to provide excellent exposure of the EOMs with minimal traction. Upon creation of the peritomy, blunt gentle dissection is carried out through adjacent, undamaged tissue quadrants (away from the suspected or injured EOM) so as not to cut residual EOM attachments inadvertently. Having a general idea of where the laceration or rupture is by clinical and radiographic exam is helpful. For example, if the wound is located posterior to the medial rectus muscle's insertion, dissection should be performed in the superonasal and inferonasal quadrants. Once this tissue is isolated from its superior and inferior attachments (or medial and lateral attachments if isolating vertical rectus muscle insertions), a muscle hook can be inserted through the quadrant dissections. Likewise, open wounds should be closed as they are encountered to reform the globe as expeditiously and judiciously as possible.

Using the Spiral of Tillaux as a geographic guide, the muscle hook is moved in the plane of the muscle, tangential to the globe and posterior to its insertion. If the muscle hook is passed too anteriorly, it may hook a pseudo-tendon or weaker connective tissue. If the EOM is attached, the more posterior dense muscle belly provides firm tactile feedback when the muscle is hooked. The surgeon should alert the anesthesia provider when hooking muscles to observe for an oculocardiac reflex. Once the muscle is hooked, blunt Westcott scissors or a cotton-tip applicator are used for gentle dissection of check ligaments and the intermuscular septum. The goal is to isolate the muscle without splitting or bruising it. Aggressive dissection is often not necessary.

Low-temperature or bipolar cautery on jeweler forceps may be necessary to achieve hemostasis but should be carefully considered near areas of exposed uveal tissue. If the EOM is bleeding because it is split, suture ligation is ideal for both hemostasis and muscle reformation.

Once the muscle is isolated, the sclera deep to it can be examined for lacerations. Most likely, the EOM will need to be detached for thorough evaluation and repair if a laceration is present. Next, a double-armed 5-0 or 6-0 absorbable polyglactin suture is placed in the middle of the muscle about 1 mm posterior to the muscle insertion. Each suture arm is passed within the muscle parallel to its insertion, exiting at the superior and inferior border if it is a horizontal rectus muscle or the medial and lateral border for a vertical rectus muscle. After the muscle is imbricated, the needle of each suture arm is reinserted back into the muscle and locked onto itself on both borders. These locking bites help to ensure the muscle does not slip.

The muscle can then be disinserted from its original insertion with blunt-tipped Westcott scissors, where the tips are placed between the muscle and suture lines. After disinsertion, the anterior and posterior muscle is inspected to ensure the muscle is contained in the suture. The globe is further examined and repaired if a laceration is present before reinsertion of the muscle. If the laceration extends more than 26 mm posterior to the muscle insertion, injury to the optic nerve should be considered.

Using a suture with a spatulated needle is helpful when reattaching the muscle. The spatulated needle is passed partial-thickness into the sclera. Oftentimes, the muscle stump of the previous insertion site leaves a suitable purchase point for reattachment. Otherwise, the muscle is reinserted 1 to 2 mm posterior to its previous insertion site barring the sclera is not compromised. Since the sclera is so thin here, the surgeon should be in a comfortable position and ensure that the patient or operating table does not move. The tip of the needle should be parallel to the sclera when starting the pass, and each arm should be about 10 mm apart in width to avoid sag in the middle of the muscle.

Management of Anteriorly Transected, Avulsed, or Retracted EOMs

Adopting the same principles above to ensure globe integrity, one should always attempt to determine if the EOM is attached to the globe. If the EOM is only partially attached to the sclera, the surgeon should survey the EOM insertion site and posterior sclera for any adherent muscle points, followed by inspection of the Tenon's capsule for the remainder of the transected muscle. If the EOM is not attached to the sclera because it is completely transected or avulsed, the surgeon should identify the anterior and posterior portions of the muscle. The EOM insertion site should be explored to determine if and how much of an anterior portion is present. If the posterior portion has retracted behind Tenon's capsule, the surgeon should locate the EOM capsule tunnel within Tenon's capsule. This can be accomplished by tracing the intermuscular septum from the adjacent rectus muscles toward the retracted EOM.

The assistant should maintain that the sleeve of the muscle pulley stays open while the surgeon searches for the retracted muscle within the sleeve. Fine, locking forceps can be used to grasp the recovered EOM and once isolated, secured, and imbricated per the technique described above. The suture bites should imbricate the axial length of the muscle and be secured with locking bites to ensure the muscle does not slip. Some surgeons may advocate for an adjustable suture to the sclera to account for the increased (from traumatic resection, contracture, or surrounding scar tissue) or decreased (from partial muscle tissue loss or palsy) new force of the recovered muscle. Adjusting the eye to orthotropia with a temporary knot can also be achieved by gauging the amount of traction or spring-back in the primary and opposing directions of the muscle when the eye is in the primary position. The extent of resistance or return can alert the surgeon to residual adhesions. These maneuvers should be performed with caution (if at all) before the primary closure of the globe.

The conjunctiva can be closed with a 6-0 plain gut or 8-0 polyglactin suture.

Antibiotic ointment with a mild steroid can be applied post-operatively.

Management of Posteriorly Transected EOMs and EOM Entrapment

Muscles that have been transected posteriorly can be difficult, if not futile, to retrieve from an anterior, transconjunctival approach described above. Access to the posterior orbit is also necessary for orbital fracture repairs and release of entrapped EOMs. The superior and lateral anterior orbit can be accessed via an upper eyelid skin crease incision, sub-brow incision, lateral canthotomy incision, or combination of these approaches where the eyelid crease or sub-brow incision is extended laterally (Stallard-Wright incision).[33]

The medial orbit can be accessed via a transcaruncular incision, medial transcutaneous (modified Lynch incision or Gullwing incision), or vertical lid split incision (Byron-Smith incision).[34] The inferior orbit can be accessed via a lower eyelid subciliary transcutaneous incision or lower lid transconjunctival incisions (where the incision is made posterior to the limbus, typically on the orbital rim). Transnasal endoscopic retrieval of the medial rectus muscle has also been described.[35] The combined efforts of an ophthalmologist and otolaryngologist may be required depending on the type of approach and experience of the orbital surgeon.

Care should be taken to isolate and avoid damage to the fascial planes or entering orbital fat to prevent orbital fat adherence and scarring.

The degree of EOM restriction from scarring or palsy from the trauma can be unpredictable, so every effort should be made to recover and repair damaged EOMs at the time of initial repair. The patient should be counseled pre-operatively (in addition to the globe or orbital fracture repair consents) that future strabismus surgery on one or both eyes may be necessary. Even if the EOM can not be retrieved, binocular vision may still be possible with a transposition procedure, though this is typically reserved for a later date.

Damage to the LPS

Traumatic ptosis, or eyelid drooping, is generally observed for at least six months before repair.[36] Adequate wound healing and tissue maturation occur during this interval.[37] In severe cases of post-traumatic scarring, the immediate repair of the aponeurotic or levator defect is advantageous in the hands of a skilled oculoplastic specialist. Typically, only the skin is closed on initial repair to avoid incorporating the septum into the closure, which can cause lagophthalmos and lid retraction. The type of repair is typically dictated by the margin reflex distance (MRD1) and how much levator function is present. Minimal ptosis with full LPS function is often corrected by Muller's muscle-conjunctiva resection; ptosis with moderate LPS function, by external levator advancement or resection; and ptosis with minimal to no LPS function, by frontalis sling procedure.[36]

Of note, in Asian populations, a thick subcutaneous fat layer and preaponeurotic fat pad protrusion preclude fibers from extending towards the skin. Thus, the orbital septum fuses to the levator aponeurosis below the superior tarsal border, and aponeurotic insertions to the eyelid skin are lower in Asian populations than their white counterparts.[38] Therefore, the patient's ethnicity can factor into the cosmetic outcome of repair, particularly if the injury is unilateral.

Complications

Serious complications after globe and orbital surgery requiring immediate intervention include:

- Endophthalmitis

- Persistent open globe wound

- Sympathetic ophthalmia

- Orbital compartment syndrome

- Orbital cellulitis

- Orbital implant impingement on the optic nerve

- Orbital implant impingement on the rectus muscle eliciting an oculocardiac reflex

- Bradycardia is caused by the oculocardiac reflex

- Scleral perforation resulting in retinal breaks, tears, or detachments

Complications also include:

- Anterior segment ischemia if multiple EOMs are transected, detached, and reattached

- Permanent mydriasis

- Infraorbital nerve hypoesthesia

- Upper or lower eyelid retraction

- Persistent diplopia

Persistent diplopia can be a complication of:

- EOM adherence to mesh or porous implants

- EOM adherence/entrapment from inadequate orbital fracture reduction

- Fibrosis from scar tissue or orbital fat adherence

- Fibrosis from a damaged trochlea or superior oblique tendon resulting in an acquired Brown syndrome (though this typically resolves)

- Inadvertently resecting too much of the EOM

- Lost or "slipped" EOM

- EOM palsy from the initial trauma

- Contracture of the antagonist muscle

Clinical Significance

To prevent a subsequent need for strabismus surgery, the extent of EOM injury during ocular and orbital emergencies is important to minimize, if not avoid. Patients with acquired strabismus from trauma suffer from diplopia and gaze disturbance, resulting in difficulties performing daily tasks. Apparent ocular misalignment negatively impacts one's ability to secure a job.[39]

Pre-operative counseling to include the possible need for future strabismus surgeries (apart from secondary surgeries related to complications from the globe or fracture repair) is vital. These patients often require long-term follow-up to address these complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Traumatic globe and orbital surgery often involve an interprofessional team approach. Management of EOMs during globe and orbital trauma often begins with emergency room medical and nursing staff. If the patient has polytrauma, trauma surgeons are also involved in the initial assessment. The patient's medical status should be optimized before surgery. In polytrauma, life-saving interventions are prioritized. In the setting of combined ocular and orbital trauma, ophthalmologists are routinely consulted along with otolaryngologists and/or oral and maxillofacial surgeons.

Ophthalmic sub-specialists, such as oculoplastic and orbital surgeons, often get involved in preoperative planning and surgery if a fracture needs repair. With few exceptions, nearly all globe and orbital trauma surgeries are performed under general anesthesia, so an anesthesiologist is also a part of the team. Prophylactic antibiotic medications are administered to prevent infection, and a pharmacist helps verify the appropriate dose and agent and ensures no drug-drug interactions. Intraoperative surgical technicians and nursing staff are vital to ensuring the appropriate equipment and medications are available. Post-operative nursing staff assists in reviewing aftercare instructions with the patient. Patients who undergo orbital surgery may require inpatient admission to monitor for retrobulbar hematoma.

Post-operative management of globe and orbital injuries is under the ophthalmologist or orbital surgeon. If residual diplopia or strabismus develops, the patient can be referred to a strabismus surgeon, who can follow the patient over time to assess for stability in ocular alignment measurements. Social workers may be employed to help certain patients keep these appointments if access to healthcare is challenging. A successful outcome can only be accomplished with this interprofessional healthcare team approach. [Level 5]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Pre-operatively, early recognition or suspicion of open globe trauma and placement of a rigid shield is an easy step to perform if an ophthalmic exam is delayed. At the same time, the patient is being treated for other trauma. In addition, managing the patient's pain and nausea can prevent unnecessary movement and intraocular and intraorbital pressure.

Intra-operatively, direct communication with the anesthesia provider on when an extraocular muscle will be manipulated can alert the anesthesia provider to medicate if an oculocardiac reflex is observed.

Post-operative education on avoiding strenuous activity, heavy lifting, or bending during the early postoperative period is imperative, as well as other sinus precautions, including no nose blowing or drinking through a straw or suction (if there is an orbital fracture). These are typically iterated by the operating surgeons and post-operative nursing team.

Post-globe repair management includes the installation of topical antibiotics and steroid eye drops. The steroid eye drop is continued until ocular inflammation is resolved and then tapered. Prolonged steroid tapers can result in elevated intraocular pressures. Often the elevation in intraocular pressure is transient and can be managed with eye drops. In cases with persistently elevated pressures or eyes refractory to conventional pressure-lowering drop therapy, the patient may need to be referred to a glaucoma specialist for surgical management.

Often an oral antibiotic is continued for a week after surgery. The antibiotic used is generally a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone. The patient should be counseled on side effects such as prolonged ventricular depolarization (QTc prolongation) and muscle tendonitis. The appropriate dose, agent, and concomitant drug interactions are monitored by a pharmacist. The use of antibiotics after orbital surgery is variable. Clear communication and consolidation of the plan for antibiotics among the ophthalmologist and orbital surgeons (if part of a different department, such as otolaryngology or oral and maxillofacial surgery), nursing staff, patient, and primary trauma team can eliminate confusion.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Long-term follow-up by the ophthalmologist and orbital surgeon should monitor the patient for possible complications including residual diplopia and EOM limitations.

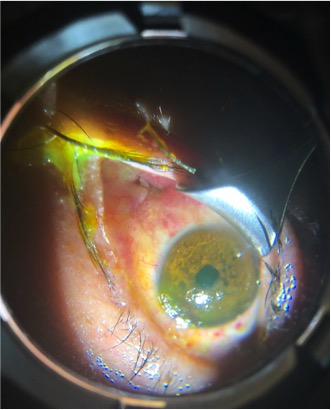

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

White MH, Lambert HM, Kincaid MC, Dieckert JP, Lowd DK. The ora serrata and the spiral of Tillaux. Anatomic relationship and clinical correlation. Ophthalmology. 1989 Apr:96(4):508-11 [PubMed PMID: 2726180]

Olsen TW, Aaberg SY, Geroski DH, Edelhauser HF. Human sclera: thickness and surface area. American journal of ophthalmology. 1998 Feb:125(2):237-41 [PubMed PMID: 9467451]

Marcon GB, Pittino R. Dose-effect relationship of medial rectus muscle advancement for consecutive exotropia. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2011 Dec:15(6):523-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.08.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22153393]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShoshany TN, Robson CD, Hunter DG. Anomalous superior oblique muscles and tendons in congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2019 Dec:23(6):325.e1-325.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2019.09.014. Epub 2019 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 31689500]

Jordan DR, Stoica B. The Gracillimus Orbitis Muscle. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Sep/Oct:33(5):e120-e122. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000842. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27930425]

von Lüdinghausen M. Bilateral supernumerary rectus muscles of the orbit. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 1998:11(4):271-7 [PubMed PMID: 9652543]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLueder GT, Dunbar JA, Soltau JB, Lee BC, McDermott M. Vertical strabismus resulting from an anomalous extraocular muscle. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 1998 Apr:2(2):126-8 [PubMed PMID: 10530977]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKrarup J, de Decker W. [Catalog of direct eye muscle injuries]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 1982 Dec:181(6):437-43 [PubMed PMID: 7169767]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePujari A, Saxena R, Sharma P, Phuljhele S. What decides the nature of extraocular muscle injury? The probable mechanism of flap tear and rupture. Medical hypotheses. 2019 Feb:123():115-117. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2019.01.011. Epub 2019 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 30696580]

Laure B, Arsene S, Santallier M, Cottier JP, Sury F, Goga D. [Post-traumatic disinsertion of the superior oblique muscle trochlea]. Revue de stomatologie et de chirurgie maxillo-faciale. 2007 Dec:108(6):551-4 [PubMed PMID: 17950768]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTakahashi Y, Sabundayo MS, Miyazaki H, Mito H, Kakizaki H. Incarceration of the inferior oblique muscle branch of the oculomotor nerve in patients with orbital floor trapdoor fracture. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2017 Oct:255(10):2059-2065. doi: 10.1007/s00417-017-3790-y. Epub 2017 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 28852825]

De Angelis D, Makar I, Kraft SP. Anatomic variations of the inferior oblique muscle: a potential cause of failed inferior oblique weakening surgery. American journal of ophthalmology. 1999 Oct:128(4):485-8 [PubMed PMID: 10577590]

Chatzistefanou KI, Kushner BJ, Gentry LR. Magnetic resonance imaging of the arc of contact of extraocular muscles: implications regarding the incidence of slipped muscles. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2000 Apr:4(2):84-93 [PubMed PMID: 10773806]

Lueder GT. Orbital Causes of Incomitant Strabismus. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2015 Jul-Sep:22(3):286-91. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.159714. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26180465]

Tooley AA, Levine B, Godfrey KJ, Lisman RD, Tran AQ, Sherman JE. Inferior Oblique Entrapment After Orbital Fracture With Transection and Repair. Craniomaxillofacial trauma & reconstruction. 2020 Sep:13(3):211-214. doi: 10.1177/1943387520928652. Epub 2020 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 33456689]

Gómez Roselló E, Quiles Granado AM, Artajona Garcia M, Juanpere Martí S, Laguillo Sala G, Beltrán Mármol B, Pedraza Gutiérrez S. Facial fractures: classification and highlights for a useful report. Insights into imaging. 2020 Mar 19:11(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s13244-020-00847-w. Epub 2020 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 32193796]

Wei LA, Durairaj VD. Pediatric orbital floor fractures. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2011 Apr:15(2):173-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.02.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21596296]

Cole P, Kaufman Y, Hollier LH Jr. Managing the pediatric facial fracture. Craniomaxillofacial trauma & reconstruction. 2009 May:2(2):77-83. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1202592. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22110800]

Rehman K, Edmondson H. The causes and consequences of maxillofacial injuries in elderly people. Gerodontology. 2002 Jul:19(1):60-4 [PubMed PMID: 12164242]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceUnger JM, Gentry LR, Grossman JE. Sphenoid fractures: prevalence, sites, and significance. Radiology. 1990 Apr:175(1):175-80 [PubMed PMID: 2315477]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWhitnall SE. A Ligament acting as a Check to the Action of the Levator Palpebrae Superioris Muscle. Journal of anatomy and physiology. 1911 Jan:45(Pt 2):131-9 [PubMed PMID: 17232869]

Ho TQ, Jupiter D, Tsai JH, Czerwinski M. The Incidence of Ocular Injuries in Isolated Orbital Fractures. Annals of plastic surgery. 2017 Jan:78(1):59-61 [PubMed PMID: 26835822]

Su Y, Shen Q, Bi X, Lin M, Fan X. Delayed surgical treatment of orbital trapdoor fracture in paediatric patients. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Apr:103(4):523-526. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-311954. Epub 2018 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 29858184]

Sugamata A. Orbital apex syndrome associated with fractures of the inferomedial orbital wall. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2013:7():475-8. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S42811. Epub 2013 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 23487509]

Brazis PW. Palsies of the trochlear nerve: diagnosis and localization--recent concepts. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1993 May:68(5):501-9 [PubMed PMID: 8479214]

Bhatti N, Kanzaria A, Huxham-Owen N, Bridle C, Holmes S. Management of complex orbital fractures. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2016 Sep:54(7):719-23. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2016.04.025. Epub 2016 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 27268464]

Wojno TH. The incidence of extraocular muscle and cranial nerve palsy in orbital floor blow-out fractures. Ophthalmology. 1987 Jun:94(6):682-7 [PubMed PMID: 3627717]

Young SM, Koh YT, Chan EW, Amrith S. Incidence and Risk Factors of Inferior Rectus Muscle Palsy in Pediatric Orbital Blowout Fractures. Craniomaxillofacial trauma & reconstruction. 2018 Mar:11(1):28-34. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1601884. Epub 2017 May 2 [PubMed PMID: 29387301]

Swamy L, Phan LT, Sadah ZM, McCulley TJ, Warwar RE. Oculocardiac reflex in a medial orbital wall fracture without clinically evident entrapment. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2013 Jul-Sep:20(3):268-70. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.114810. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24014996]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePham CM, Couch SM. Oculocardiac reflex elicited by orbital floor fracture and inferior globe displacement. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2017 Jun:6():4-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2017.01.004. Epub 2017 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 29260043]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAhmed Y, Schimel AM, Pathengay A, Colyer MH, Flynn HW Jr. Endophthalmitis following open-globe injuries. Eye (London, England). 2012 Feb:26(2):212-7. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.313. Epub 2011 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 22134598]

Hauser CJ,Adams CA Jr,Eachempati SR,Council of the Surgical Infection Society., Surgical Infection Society guideline: prophylactic antibiotic use in open fractures: an evidence-based guideline. Surgical infections. 2006 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 16978082]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLee RP, Khalafallah AM, Gami A, Mukherjee D. The Lateral Orbitotomy Approach for Intraorbital Lesions. Journal of neurological surgery. Part B, Skull base. 2020 Aug:81(4):435-441. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1713904. Epub 2020 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 33072483]

Osguthorpe JD, Saunders RA, Adkins WY. Evaluation of and access to posterior orbital tumors. The Laryngoscope. 1983 Jun:93(6):766-71 [PubMed PMID: 6304435]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLenart TD, Reichman OS, McMahon SJ, Lambert SR. Retrieval of lost medial rectus muscles with a combined ophthalmologic and otolaryngologic surgical approach. American journal of ophthalmology. 2000 Nov:130(5):645-52 [PubMed PMID: 11078843]

Jacobs SM, Tyring AJ, Amadi AJ. Traumatic Ptosis: Evaluation of Etiology, Management and Prognosis. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2018 Oct-Dec:13(4):447-452. doi: 10.4103/jovr.jovr_148_17. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30479715]

Stadelmann WK, Digenis AG, Tobin GR. Physiology and healing dynamics of chronic cutaneous wounds. American journal of surgery. 1998 Aug:176(2A Suppl):26S-38S [PubMed PMID: 9777970]

Jeong S, Lemke BN, Dortzbach RK, Park YG, Kang HK. The Asian upper eyelid: an anatomical study with comparison to the Caucasian eyelid. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1999 Jul:117(7):907-12 [PubMed PMID: 10408455]

Mojon-Azzi SM, Mojon DS. Strabismus and employment: the opinion of headhunters. Acta ophthalmologica. 2009 Nov:87(7):784-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01352.x. Epub 2008 Oct 30 [PubMed PMID: 18976309]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence