Introduction

Intermittent exotropia is the most common type of strabismus. It is defined as a non-constant exodeviation that manifests predominantly at distance fixation and may progress over a variable period to near fixation. This entity is also named distance exotropia, divergent squint, periodic exotropia, or exotropia of inattention. Small exophorias are common in newborns and can be present in 60 to 70%, which resolves by 4 to 6 months of age. This condition often presents in childhood.

The usual disease course begins with an exophoria that may progress to intermittent exotropia and eventually become constant. It is important to understand that all cases are not progressive, as some cases might remain stable over the years despite lack of treatment, and few may even improve. Von Noorden, in his analysis, found that among 51 untreated patients with intermittent exotropia, 75% showed progression, 9% remained stable, and 16% showed improvement.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of intermittent exotropia is not very clearly defined. However, the following theories have been proposed by different researchers, which explains the underlying pathogenesis.

- Innervational factors: Duane proposed that exodeviations occur secondary to innervational imbalance, which upsets the reciprocal relationship between active convergence and divergence mechanisms.[2]

- Mechanical factors: Bielschowsky suggested the role of the abnormal position of rest associated with exodeviations. This abnormal position is determined by anatomic and mechanical factors such as the orientation of orbit, shape, and size of orbits and globes, volume and viscosity of retrobulbar tissue, insertion, and functioning of the eye muscles, length, elasticity, the anatomical and structural arrangement of fascias and ligaments of the orbits.[3]

- Fusion faculty: Any obstacle which causes disturbance in binocular vision can lead to deviation of eyes. A defect of the fusion faculty has been suggested as the essential cause of squint. An inadequate fusion faculty of eyes lead to an unstable state of equilibrium, and eyes deviate inwards or outwards even on slight provocation.[4]

- AC/A ratio: Cooper and Medow proposed the role of high accommodative convergence/accommodation ratio in intermittent exotropias.[5] Kushner later found that close to 60% of patients with true divergence exotropias had a high AC/A ratio, and 40% had a normal AC/A ratio.[6]

- Refractive errors: Underlying uncorrected refractive errors have been postulated as a mechanism for exodeviations. Among uncorrected myopes, lesser than normal accommodative effort is needed for near vision. This decreased accommodative convergence has been described as the underlying cause for increased exodeviations among myopes.[7] Similarly, in uncorrected high hyperopes, clear vision is unattainable even with maximum accommodative accommodation or leads to asthenopic symptoms.[8] This results in an underactive convergence mechanism that causes a low AC/A ratio.

Anisomyopia and anisometropia result in unclear retinal images, which function as an obstacle to binocular fusion and thus facilitate suppression. This again predisposes to exodeviations.[9]

Epidemiology

The majority of cases of exodeviations start shortly after birth. In a study of 472 patients with intermittent exotropia, 204 had the deviation from birth, appeared around the age of 6 months among 16 patients, and between 6 to 12 months among 72 patients.[12] A study from China reported the prevalence of intermittent exotropia in the study population as 3.24%.[13]

Most studies describe a preponderance of female patients in exotropia. Another study of 10 years duration from the United States found 205 children with exotropia. An annual incidence of 64.1 of 100,000 patients was found among children lesser than 19 years of age.[14] Among these, 86% had either an intermittent exotropia, or an underlying convergence insufficiency, or a central nervous system pathology with an exotropia.

History and Physical

Patients with intermittent exotropia are often asymptomatic. The most common presentation is parents reporting either closure of one eye by the child when going in bright light or an occasional deviation noticed, particularly when the child is daydreaming or physically tired. Most patients are asymptomatic, which is related to a well-developed suppression mechanism. In addition, patients often exhibit normal retinal correspondence when the eyes are aligned but abnormal retinal correspondence on sensory testing when one eye deviates.

Various symptoms that may be reported in patients with intermittent exotropia are as follows.

- Transient Diplopia: Occasionally, patients may complain of intermittent binocular horizontal double vision or discomfort associated with eye deviation.

- Asthenopic symptoms are experienced in the initial phases when fusion begins to succumb and eyes deviate from the ortho position. Patients may complain of eyestrain, blurring, headache, and difficulty with prolonged reading.

- Diplophotophobia: Closure of one eye in bright sunlight. Bright sunlight dazzles the retina, disrupting the fusion and thus causing the deviation to manifest.[15]

- Micropsia: This can occur as a result of accommodative convergence to control the deviation.

Classification of Intermittent Exotropia: Burian classified intermittent exotropia into 4 groups based on distance and near deviations.[16] The differences are based on underlying fusional convergence and divergence mechanisms. The 4 types include:

- Basic type: when the difference between the distance deviation and near deviation is less than 10 prism diopters. These patients have normal fusional, accommodation, AC/A ratio, and proximal convergence.

- True divergence excess: after a patch test, the distance deviation exceeds the near deviation by at least 10 prism diopters. These patients can be associated with a high or a normal AC/A ratio. Patients with a high AC/A ratio have a potential for overcorrection if surgery is performed based on the distance deviation.

- Convergence insufficiency: the deviation for near exceeds the deviation for distance by at least 10 prism diopters.

- Pseudo-divergence excess: when distance deviation exceeds the near deviation by more than 10 prism diopters, but after monocular patch test, the difference between distance and near deviation decreases to less than 10 prism dioptres. The patch test breaks the associated higher tonic fusional convergence in these patients, and thus an increase in near deviation is noticed following this test bringing the near deviation close to distance deviation values. This has been described by Kushner as tenacious proximal fusion.[17]

Kushner modified this classification and expanded this to add categories like tenacious proximal fusion, high AC/A ratio, low AC/A ratio, proximal convergence, and pseudo-convergence insufficiency.[6]

Evaluation

Intermittent exotropia is a clinical diagnosis and does not need any specific laboratory or radiographic tests. It is important to do a detailed assessment of the control and measure the deviation. These patients usually have bilateral good vision and freely alternating fixation. However, patients with strabismic amblyopia might show a fixation pattern. The deviations are usually comitant, and ocular movements are full and free. A complete sensory and motor examination should be performed and deviations measured for near, distance, and all the 9 diagnostic gazes. This is useful in monitoring the deterioration or progression of exotropia on follow-up visits. The basic evaluation can be divided into:

Subjective Methods

The control of exodeviation is assessed using New Castle Scoring and divided into Home control and Office control. Scoring is done for each patient from 0 to 9, with 0 corresponding to the best control and 9 to the worst control.[18][19]

Home Control – Exodeviation noticed

- Never – 0

- <50% of the time when the child is awake, appears for distance only - 1

- >50% of the time when the child is awake, appears for distance only - 2

- Squinting observed for distance as well as for near fixation – 3

Office Control – while fixating at distance

- Manifests only after cover test, and re-fixates without need for blink (good) – 0

- Blinks or re-fixates after the cover test (fair) - 1

- Exotropia remains manifested after cover test, and no recovery happens even with blinking - 2

- Manifests exotropia spontaneously (poor) - 3

Office Control – while fixating at near

- Manifests only after cover test, and re-fixates without need for blink (Good) – 0

- Blinks or re-fixates after the cover test (Fair) - 1

- Exotropia remains manifested after cover test, and no recovery happens even with blinking - 2

- Manifests exotropia spontaneously (Poor) - 3

Total score = Home control+ Office control (distance) + Office control (near)

Objective Methods

- Distance Stereoacuity – Distance stereo acuity provides an objective assessment of the control of deviation. It is a significant indicator of the deterioration of fusion. Normal distance stereo acuity indicates good control with little or no suppression.[20][21]

- Near Stereoacuity - Near stereo acuity does not correlate well with the degree of control in intermittent exotropia.[22] This has a limited role in deciding for management of the patient.

- Measuring the angle of deviation – Patients with intermittent exotropia need a prolonged alternate cover test to break the tenacious proximal fusion and reveal full deviation. A patch test is advised if there is a significant difference in near and distance deviations.[23]

- 9 gaze measurements - Intermittent exotropia may be associated with other eye movement anomalies, mainly overaction of the inferior oblique muscle and lateral incomitance (a decrease in the amount of exodeviation on side gaze).[24]

- Patch test – This is indicated when there is a near-distance deviation disparity. The patch test is used to dissociate the tonic fusional convergence and helps in differentiating true divergence excess from pseudo-divergence excess. The patch is applied to one eye for 30 minutes, and measurements are repeated after removing the patch without allowing the eyes to fuse in-between.

- Lens Gradient Method – This test is used to identify patients with true divergence excess exodeviations associated with a high AC/A ratio. This test is performed in patients who have a disparity between distance and near deviation, with distance deviation exceeding near deviation by ≥10 prism dioptres after the patch test. After the patch test with eyes being still dissociated, the measurements are repeated for near with a +3D add. If the near deviation increases by 20prism diopters or more for near after the lens gradient method, a diagnosis of true divergence excess intermittent exotropia with a high AC/A ratio is made. The importance of this test lies in the fact that these patients will also have distance-near disparity post-surgical correction and will need bifocal spectacles to control consecutive esotropia for near.[25]

- Far distance measurement – This is done by measuring the deviation by asking the patient to fixate at a far distance rather than at 6 meters. This test helps in uncovering the full deviation by reducing near convergence. A prospective randomized trial showed that 86% of the patients who had surgery for the maximum angle of deviation had a satisfactory outcome, compared to 62% in the group who were operated for the standard deviations measured with a 6-meter target deviation measurements.[26]

Treatment / Management

Management of intermittent exotropia varies from observation to non-surgical or surgical intervention based on the patient's deviation, control, and complaints. A prospective observational study of 183 children between 3 and 10 years old with intermittent exotropia showed that the probability of deterioration at 3 years (constant exotropia or decline in stereopsis) was 15%.[27] Another retrospective study of patients between 5 and 25 years showed that without surgery, the angle of deviation remained stable among 58%, improved in 19%, and worsened in 23%.[28](B2)

Non-surgical Treatment

The aim is to encourage the use of both the eyes together by elimination of suppression), aiding recognition of double vision when eyes are misaligned, and building fusional reserves to control the exodeviation. This may be preferred in patients with small (<20prism diopter) deviations, very young patients in whom accurate measurements cannot be made, or surgical overcorrection could lead to amblyopia or loss of fixation.[29] Additionally, patients with a high AC/A ratio may be responsive to non-surgical methods. The various non-surgical management options include:

- Correction of Refractive Error: Uncorrected refractive errors can impair fusion and thus lead to manifest deviations. Cycloplegic refraction should be done in all patients, and a trial of corrective lenses advised. This is particularly beneficial in myopic patients, who might regain their control with refractive correction alone.[30]

- Orthoptics: These may be used to improve the control of the deviation. The aim is to make the patient aware of the manifest deviation. Convergence exercises are helpful in patients with a remote near the point of convergence or who demonstrate poor fusional convergence amplitudes. Active anti-suppression and diplopia awareness techniques are useful in patients with suppression.

- Overcorrecting minus lenses: This is based on the principle of stimulating accommodative convergence and thus reducing an exodeviation.[31][32]

- Part-time occlusion: This is a passive anti-suppression technique, particularly useful for very young children. Alternate eye occlusion should be advised in patients with equal fixation patterns. This may result in improved control of the deviation, although long-term results are not well studied.[33] A multi-center, randomized, controlled trial assessed the role of patching in children from 3 to 10 years with intermittent exotropia.[34] Children were randomized to observation versus 6 months of 3 hours of daily patching. At 6 months, the rate of deterioration in both groups was low, suggesting that both observation and patching are reasonable management options.

- Prismotherapy: The conventional approach includes the use of a base in prism to enhance bifoveal stimulation. Large amounts of prisms are often required, which might deteriorate vision quality and lead to low compliance.[35]] (A1)

Surgical Treatment

Indications for surgery include preservation or restoration of binocular function and cosmesis. One of the important indications for surgical intervention in intermittent exotropia is an increased frequency or duration on tropia since this indicates deteriorating fusional control. Signs of progression of intermittent exotropia include: gradual loss of fusional control noticed by the increasing frequency of manifest phase of squint, development of secondary convergence insufficiency, increase in the size of basic deviation, development of suppression, and decrease in stereo acuity.

The different surgical approaches include:

- Unilateral medial rectus muscle resection combined with a lateral rectus muscle recession

- Bilateral lateral rectus muscle recessions.

The choice of surgery depends on the surgeon’s preference. Few support bilateral symmetric surgery to avoid horizontal incomitance and prevent the palpebral fissure narrowing that can be associated with horizontal rectus muscle resections. Few authors have advocated bilateral lateral rectus recessions as superior in patients with true divergence excess intermittent exotropia. Most of the surgeons prefer operating for the largest distance deviation that can be documented repeatedly.[26](A1)

- Lateral Incomitance – Patients with preoperative lateral incomitance are likely to be overcorrected with surgery.[36] Thus, reducing the amount of recession is suggested, especially if the deviation in lateral gaze is 50% less than the deviation in the primary position.

- A-and V-patterns: Intermittent exotropia may be associated with inferior or superior oblique overactions and thus A- and V-pattern. In patients with inferior oblique overaction and a significant V-pattern, the inferior oblique weakening should be considered at the time of the horizontal muscles surgery. If significant superior oblique overaction and an A-pattern is present, either an infra placement of the lateral rectus muscles or a superior oblique weakening procedure should be considered. Small vertical deviations with no significant patterns should be ignored since these vertical phorias less than 8 prism diopters usually only disappear after horizontal muscle surgery.

Botulinum toxin injection is also an option for intermittent exotropia, though not much explored. A nonrandomized, case-controlled study among children from ages 3 to 144 months with intermittent exotropia showed results similar to surgical intervention. These children received 2.5 units of Botox injection into each lateral rectus muscle. Results showed that 69% of patients were orthophoric 12 to 44 months following the Botox injection.[37](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The close differentials of intermittent exotropia include all other forms of exotropia, which can be distinguished based on history and clinical examination. These include

- Constant exotropia: This usually appears within the first 6 months of life. This is constant and does not resolve spontaneously.

- Sensory exotropia: This is usually seen in patients with poor visual function in one eye. This develops in an older child or an adult as the eye with defective vision starts drifting gradually.

- Consecutive exotropia: This refers to exotropia in a previously esotropic eye. This can result secondary to surgical overcorrection or spontaneous consecutive exotropia in a deviating eye with poor vision.

- Duane's retraction syndrome – This condition is characterized by variable limitation of adduction or abduction and can present as exotropia or esotropia or an orthotropia. Ocular movements, palpebral fissure changes, and, if needed, electromyography can help differentiate this condition.

Prognosis

There is a lack of standard definition for surgical success in patients with intermittent exotropia. The different treatment approaches, differences in intervention time, and paucity of long-term follow-ups further add to the ambiguity. Most of the studies considered a residual misalignment of ≤ 10 prism diopters as surgical success. Various studies with different duration of follow-ups have shown variable success rates. The success rates in previous literature vary from 50% to 80%, with a follow-up varying from 6 months to 5 years, with a longer duration of follow-ups showing lesser success rates. Recent studies have also reported variable success rates in all types of intermittent exotropia, around 40 to 70%.[38][39][40]

Kushner compared the surgical results for different degrees of intermittent exotropia, surgical procedure, amount of surgical dosage and drew the following conclusions:[26]

- Patients with high AC/A are at high risk of developing consecutive esotropia at near.

- Patients with tenacious proximal fusion have a better chance of surgical success.

- The surgery in patients with intermittent exotropia should be planned based on the maximum deviation documented consistently for the patient.

Complications

The complications associated with surgical correction are similar as related to any squint surgery. These can be divided into related to anesthesia or the surgical process (intraoperative or postoperative).

Anesthesia-related

- Oculocardiac reflex

- Malignant hyperthermia

- Cardiac arrest

- Hepatic porphyria

- Succinylcholine–induced apnoea

Surgical Complications

Intraoperative

- Hemorrhage

- Lost or slipped muscle

- Inadvertent injury to surrounding structures

- Globe perforation,

- Wrong muscle, or wrong eye surgery

Postoperative

- Diplopia

- Monofixation syndrome

- Loss of stereopsis

- Suture reaction

- Conjunctival granuloma

- Anterior segment ischemia

- Retinal detachment

- Under or overcorrections

- Adhesive syndrome[41]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Postoperative treatment depends on the alignment of the eyes. The patient may complain of diplopia, eyes can be in the ortho position, or have residual exodeviations or a consecutive esotropia.

- Orthotropia: In small children, a small esotropia of 8 to 10 prism diopters is ideal in young patients because of the natural tendency of the eyes to deviate outside postoperatively. In patients with orthotropia immediately, post-operative orthoptic exercises should be advised to strengthen the positive fusional convergence. This will enable control of the newly acquired bifoveal single vision.

- Consecutive Esotropia: A residual esotropia of up to 10 prism diopters is ideal. Even patients with up to 20 prism diopters of residual esotropia may resolve over time. Non-surgical measures should be tried for at least 1 month, as there are high chances of spontaneous resolution.

Children

There are high chances of monofixation syndrome and suppression of amblyopia. Therefore, the following measures are advocated within 2 weeks post-surgery.

- Refraction using cycloplegics should be done, and any hypermetropic should be fully corrected.

- Bifocals – if there is greater near deviation present post-surgery.

- Occlusion therapy – part-time alternate eye patching or monocular patching based on the fixation pattern.

- Prismotherapy – Fresnel prisms can be advised to fully correct the deviation and maintain bifoveal fixation.

A decision for repeast surgery should be taken if the child remains overcorrected by more than 15 prism diopters, despite the non-surgical measures.

Adults

In patients with a visually mature system, an overcorrection of more than 20 prism diopters, nonsurgical measures may be tried after a watch period of 6 to 8 weeks. As explained above, the same options of non-surgical treatment in the form of hypermetropic correction, bifocals, or prismotherapy might be considered. Any decision for repeat surgery should only be after 6 months post-surgery.

Residual Exotropia

- Small residual exotropia (15 to 18 prism diopters) – These patients can be managed with non-conservative measures.

- Optical correction – A full correction should be given for any underlying myopic refraction.

- Cycloplegics – Hypermetropes or emmetropes patients can be started on 1% cyclopentolate eye drops twice a day to stimulate accommodative convergence.

- Orthoptic exercises – anti suppression exercises or fusional exercises should be continued till alignment is obtained.

- Prismotherapy – base-in-prisms equal to fully neutralize the deviation may be helpful to avoid diplopia and maintain bifoveal fusion.

- Large residual exotropia (15 to 18 prism diopters) - Patients with a large residual exotropia in the first postoperative week will probably require additional surgery. It is better to wait for 8 to 12 weeks before re-operating for the residual exotropia. If the primary surgery was bilateral lateral rectus recession of 6 mm or less, re-recession of the lateral rectus might be planned. If the primary recession was greater than 6 mm, bilateral medial rectus resections with a conservative approach might be planned, as overcorrections are common after resecting against a large recession.

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is important to educate the patients and involve parents/guardians in decision-making and management. In young patients with good control and small-angle deviations, an observation alone might be sufficient. At times patching with close observation or orthoptics exercises might be needed. The management plan needs to be discussed with parents, and their involvement is mandatory to ensure children are following the treatment correctly.

Parents should be explained that orthoptics exercises might help in delaying the surgery. The need for regular follow-ups and involvement of parents to assess the home control should be well discussed. A detailed discussion should be done about the risks and benefits associated with different management options. They should also be hinted at the possible impact of strabismus on the child’s psychological health and its effect on social behavior and education.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with intermittent exotropia require a detailed evaluation by clinicians, orthoptists, and ophthalmic technicians. The health staff should discuss the underlying possible pathogenesis of the condition and help the parents make a correct choice of management. They should play an active role by ensuring treatment compliance in the form of patching or orthoptics exercises. These patients should be followed up closely by the healthcare team, who would also help in better decision-making when surgical intervention is needed.

The team members should be well versed with post-operative care instructions and the correct administration of eye drops. They should explain to the patient/parents the red-flag symptoms/signs during the follow-up, which should be addressed at the earliest possible opportunity. They should understand their role in the patient’s treatment, evaluation at each visit, discuss the future treatment plan and ensure compliance and regular follow-ups.

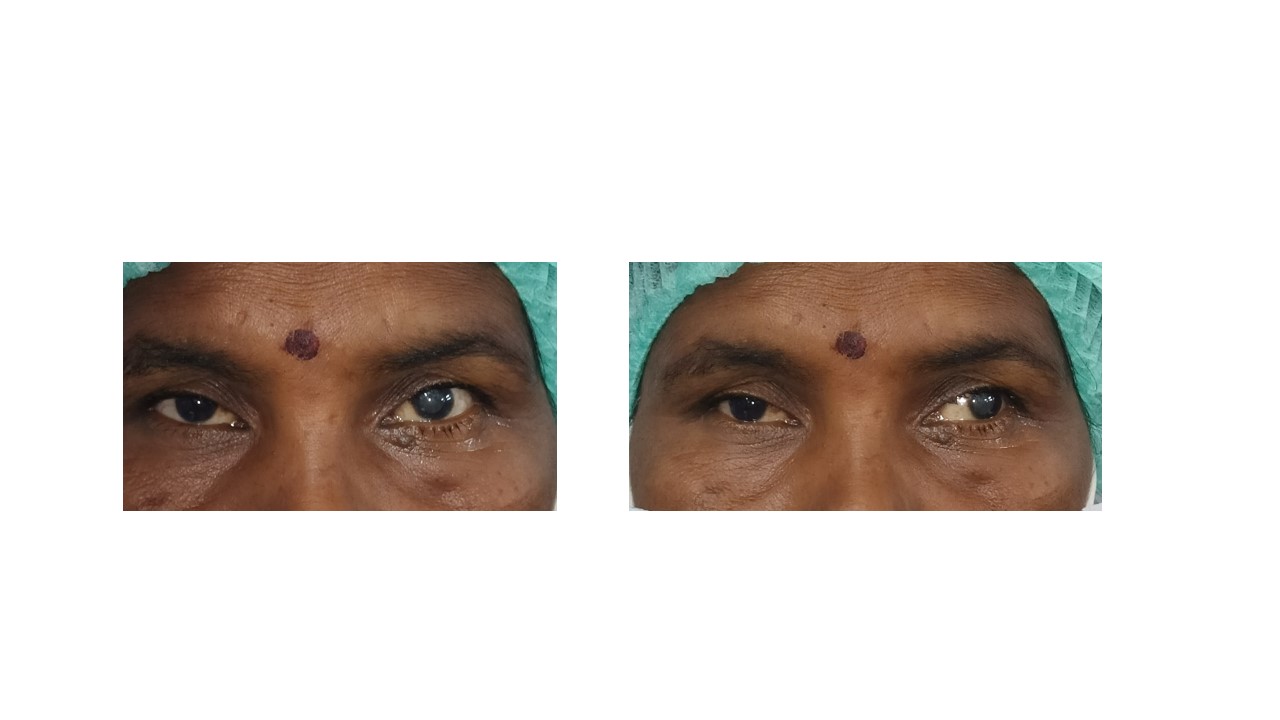

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Video to Play)

References

Tang W,He B,Luo J,Deng Z,Wang X,Duan X, Effect of the Control Ability on Stereopsis Recovery of Intermittent Exotropia in Children. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2021 Aug 1; [PubMed PMID: 34435904]

Lee JY,Park KA,Oh SY, Lateral rectus muscle recession for intermittent exotropia with anomalous head position in type 1 Duane's retraction syndrome. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2018 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 30062561]

Wu Y,Peng T,Zhou J,Xu M,Gao Y,Zhou J,Hou F,Yu X, A Survey of Clinical Opinions and Preferences on the Non-surgical Management of Intermittent Exotropia in China. Journal of binocular vision and ocular motility. 2021 Aug 27; [PubMed PMID: 34449280]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBui Quoc E, Milleret C. Origins of strabismus and loss of binocular vision. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience. 2014:8():71. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2014.00071. Epub 2014 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 25309358]

Cooper J, Intermittent exotropia of the divergence excess type. Journal of the American Optometric Association. 1977 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 908827]

Kushner BJ,Morton GV, Distance/near differences in intermittent exotropia. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1998 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 9565045]

Kekunnaya R,Chandrasekharan A,Sachdeva V, Management of Strabismus in Myopes. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2015 Jul-Sep; [PubMed PMID: 26180467]

von Noorden GK,Avilla CW, Accommodative convergence in hypermetropia. American journal of ophthalmology. 1990 Sep 15; [PubMed PMID: 2396654]

JAMPOLSKY A,FLOM BC,WEYMOUTH FW,MOSES LE, Unequal corrected visual acuity as related to anisometropia. A.M.A. archives of ophthalmology. 1955 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 13268145]

KNAPP P, Intermittent exotropia: evaluation and therapy. The American orthoptic journal. 1953 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 13104828]

JAMPOLSKY A, Differential diagnostic characteristics of intermittent exotropia and true exophoria. The American orthoptic journal. 1954 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 13180847]

Audren F, [Intermittent exotropia]. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2019 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 31301849]

Pan CW,Zhu H,Yu JJ,Ding H,Bai J,Chen J,Yu RB,Liu H, Epidemiology of Intermittent Exotropia in Preschool Children in China. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 2016 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 26583796]

Govindan M,Mohney BG,Diehl NN,Burke JP, Incidence and types of childhood exotropia: a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2005 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 15629828]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKelkar JA,Gopal S,Shah RB,Kelkar AS, Intermittent exotropia: Surgical treatment strategies. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2015 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 26458472]

BURIAN HM,SPIVEY BE, THE SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF EXODEVIATIONS. American journal of ophthalmology. 1965 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 14270998]

Wang X,Wang F,Xi S,Jiang C,Liu Y,Wen W,Zhao C, Short-Term Near Stereoacuity Improvements Following Favorable Surgical Alignment in Exotropic and Esotropic Patients. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2021 Jul 5; [PubMed PMID: 34223803]

Haggerty H,Richardson S,Hrisos S,Strong NP,Clarke MP, The Newcastle Control Score: a new method of grading the severity of intermittent distance exotropia. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2004 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 14736781]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBuck D,Clarke MP,Haggerty H,Hrisos S,Powell C,Sloper J,Strong NP, Grading the severity of intermittent distance exotropia: the revised Newcastle Control Score. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 18369078]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStathacopoulos RA,Rosenbaum AL,Zanoni D,Stager DR,McCall LC,Ziffer AJ,Everett M, Distance stereoacuity. Assessing control in intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 1993 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 8479706]

Sharma P,Saxena R,Narvekar M,Gadia R,Menon V, Evaluation of distance and near stereoacuity and fusional vergence in intermittent exotropia. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Mar-Apr; [PubMed PMID: 18292622]

Zanoni D,Rosenbaum AL, A new method for evaluating distance stereo acuity. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 1991 Sep-Oct; [PubMed PMID: 1955959]

Kaur K,Gurnani B, Dissociated Vertical Deviation StatPearls. 2021 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 34424634]

Barrett BT, A critical evaluation of the evidence supporting the practice of behavioural vision therapy. Ophthalmic [PubMed PMID: 19154276]

Jackson JH,Arnoldi K, The Gradient AC/A Ratio: What's Really Normal? The American orthoptic journal. 2004; [PubMed PMID: 21149096]

Kushner BJ, The distance angle to target in surgery for intermittent exotropia. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1998 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 9488270]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group.,Writing Committee.,Mohney BG,Cotter SA,Chandler DL,Holmes JM,Wallace DK,Yamada T,Petersen DB,Kraker RT,Morse CL,Melia BM,Wu R, Three-Year Observation of Children 3 to 10 Years of Age with Untreated Intermittent Exotropia. Ophthalmology. 2019 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 30690128]

Romanchuk KG,Dotchin SA,Zurevinsky J, The natural history of surgically untreated intermittent exotropia-looking into the distant future. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2006 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 16814175]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHutchinson AK, Intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology clinics of North America. 2001 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 11705139]

Iacobucci IL,Archer SM,Giles CL, Children with exotropia responsive to spectacle correction of hyperopia. American journal of ophthalmology. 1993 Jul 15; [PubMed PMID: 8328547]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCaltrider N,Jampolsky A, Overcorrecting minus lens therapy for treatment of intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 1983 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 6657190]

Watts P,Tippings E,Al-Madfai H, Intermittent exotropia, overcorrecting minus lenses, and the Newcastle scoring system. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2005 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 16213396]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFreeman RS,Isenberg SJ, The use of part-time occlusion for early onset unilateral exotropia. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 1989 Mar-Apr; [PubMed PMID: 2709283]

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group.,Cotter SA,Mohney BG,Chandler DL,Holmes JM,Repka MX,Melia M,Wallace DK,Beck RW,Birch EE,Kraker RT,Tamkins SM,Miller AM,Sala NA,Glaser SR, A randomized trial comparing part-time patching with observation for children 3 to 10 years of age with intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 2014 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 25234012]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePratt-Johnson JA,Tillson G, Prismotherapy in intermittent exotropia. A preliminary report. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 1979 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 550916]

Moore S, The prognostic value of lateral gaze measurements in intermittent exotropia. The American orthoptic journal. 1969; [PubMed PMID: 5792797]

Spencer RF,Tucker MG,Choi RY,McNeer KW, Botulinum toxin management of childhood intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 1997 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 9373104]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePineles SL,Deitz LW,Velez FG, Postoperative outcomes of patients initially overcorrected for intermittent exotropia. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2011 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 22153394]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBae GH,Bae SH,Choi DG, Surgical outcomes of intermittent exotropia according to exotropia type based on distance/near differences. PloS one. 2019; [PubMed PMID: 30908548]

Lee CM,Sun MH,Kao LY,Lin KK,Yang ML, Factors affecting surgical outcome of intermittent exotropia. Taiwan journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Jan-Mar; [PubMed PMID: 29675346]

Olitsky SE,Coats DK, Complications of Strabismus Surgery. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2015 Jul-Sep; [PubMed PMID: 26180463]