Definition/Introduction

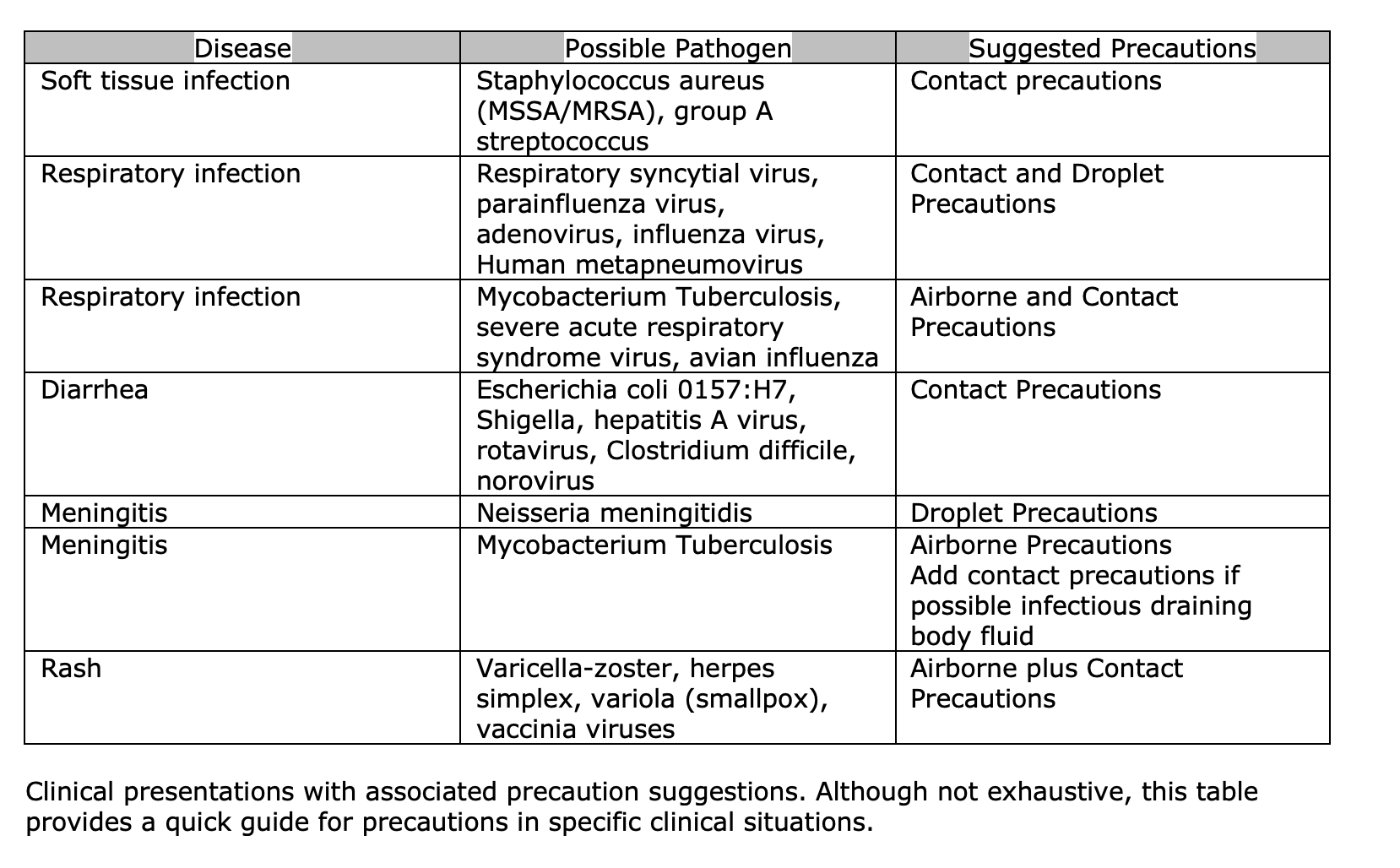

Personal protective equipment (PPE) came into the spotlight at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, but these important materials and practices have been protecting healthcare providers for years. Regulation of PPE standards usually falls to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). The availability, application, and disposal of PPE play an essential role in a healthcare system's ability to care for patients safely.[1] Part of standard precautions, PPE provides a barrier to minimizing workplace hazards that healthcare providers encounter from harmful exposures. Chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear contamination threats are encountered throughout healthcare. This article discusses the application of PPE in relation to healthcare. See Table. Personal Protective Equipment Clinical Presentations and Recommended Precautions.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Types of Personal Protective Equipment

Commonly worn PPE includes a gown, gloves, masks, respirators, and face shields or goggles. Understanding the limitations and proper wearing of PPE is essential to ensuring safe practices. Specific gloves offer differing levels of standards for infection prevention. One commonly used metric in glove safety evaluation is the acceptable quality level (AQL). A lower AQL means a higher quality glove with less micro-perforation potential and fewer pinholes in the glove product. The FDA generally recommends a minimum AQL level of 1.5 for surgical gloves and 2.5 for medical exam gloves.[2]

Surgical procedural evidence supports using two layers of gloves as an infection prevention technique.[3][4] Surgical procedures also necessitate using sterile gloves, which have been treated to eliminate microbes.

The availability of appropriate gowns can prevent the spread of infection. Medical gowns follow the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), the Association of the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI), and the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) ANSI/AAMI PB70 standards for medical gowns. The ANSI/AAMI PB70 has four levels of fluid barrier protection.[5]

USP 800 guidelines promote safety by outlining gown standards for handling hazardous drugs. Following suggested guidelines for PPE in the appropriate setting, whether using sterile gowns for surgery or non-sterile gowns for contact exposure, will ensure the safety of both healthcare workers and patients.[6][7]

Loosely woven cloth masks provide the least respiratory protection, while National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) approved respirators offer the most protection.[8][9] A key component of mask protection involves the proper fitting of masks.[10] All healthcare workers should be fit tested if required to use respirators, including N95 masks.[11][12]

If fit testing cannot be completed, then a NIOSH-approved powered air purifying respirator (PAPR) can be considered based on institutional and local regulatory requirements.[13][14][15] The COVID-19 pandemic created a high demand for face coverings with limited consistent standards comparing different products. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) and NIOSH updated barrier face covering standards, ASTM F5302-21, allowing comparison between different barrier face coverings.[16]

Standard Precautions

Standard precautions serve as a framework all healthcare providers should follow as part of an initial approach to limiting exposure. These preventative steps should be considered for every patient encounter.[17][18][19][20]

Standard precaution components are listed here:

- Hand hygiene, including hand washing, regardless if gloves are worn, before and after contact with a patient or bodily fluids[21][22][23]

- Appropriate use of PPE, including gown, gloves, and eye protection, especially if there is a risk of bodily fluid exposure

- Respiratory/cough etiquette to prevent droplet transmission of respiratory pathogens

- Patient placement with consideration for single patient rooms and routes of transmission for specific infectious agents

- Safe needle and instrument handling

Infection Prevention

PPE infection prevention recommendations can be categorized into specific transmission-based precautions. Following these recommendations, in addition to standard precautions, can protect healthcare providers and patients from disease infection. Clinical presentations giving concern for certain organism exposures require different standards of transmission prevention.[24][25] Please see Table 1.[26][27]

Contact precautions require the use of a gown and gloves in clinical situations involving organisms spread by direct or indirect contact with a patient or patient's environment. For example, clinical scenarios involving wound drainage, fecal matter, or other bodily discharge exposure would suggest using contact precautions.[28][29]

Droplet precautions should be utilized in respiratory illness where close mucous membrane contact or respiratory droplet exposure may occur. Droplet precautions should include standard precautions, eye protection, and a mask. Generally, pathogens requiring droplet precautions do not remain infectious over extended distances. Eye protection and an N-95 mask or higher-level respirator should be utilized with standard precautions in the setting of airborne precautions. Airborne pathogens have long-distance exposure potential that necessitates the need for special air handling and ventilation systems. These ventilation systems should meet the Architects Facility Guidelines Institute standards for airborne infection isolation rooms. Easily visible signs should be placed outside patient rooms and contact zones listing the required PPE for a specific patient encounter.[26]

Chemical and Nuclear Personal Protective Equipment

Healthcare providers may come into contact with harmful chemicals as part of day-to-day activity. Whether in the form of cleaning, pharmaceutical, or contamination, exposures are a risk at several points throughout regular workplace flow. In the event of exposure to workplace-stocked chemicals, Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) should be referenced for information specific to each chemical. Standard PPE should be utilized in the setting of chemical handling as defined by OSHA and CDC. Considerations should be made for areas of safe chemical handling, including adequate ventilation, safe handling areas, cleaning work surfaces, and spill procedures. In the scenario where a healthcare provider must enter a contaminated area with appropriate hazardous materials (HAZMAT), PPE must be utilized.[30][31][32]

HAZMAT equipment PPE recommendations follow OSHA standards as outlined by Levels A, B, C, and D. Different levels of protection are offered in each guideline, from the highest level of protection, Level A, including self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) to Level D least protective including standard precautions and appropriate work uniform. Level A PPE should be utilized when the hazardous substance requires the highest level of eye, skin, and respiratory protection.[33][34]

Level A PPE guidelines are also followed when entering areas of poor ventilation or when a substance has not yet been identified as appropriate for a lower level of protection. Level B PPE provides protection in areas requiring a high level of respiratory protection, including scenes with less than 19.5% oxygen or incompletely identified vapors/gasses. Level C PPE protection is appropriate in situations necessitating air-purifying respirators and contaminants which will not cause adverse harm through exposed skin. Level D PPE would be utilized when no known hazard is present in the atmosphere and contact or inhalation with hazardous levels is precluded by work functions. Other PPE may be included as defined by specific sceneries and OSHA recommendations. Part of the appropriate response to chemical exposure also includes decontamination processes in addition to proper disposal of used PPE.[35]

Recommendations for nuclear hazardous materials come from OSHA guidelines regarding events involving chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) agents.[36] Recommendations for specific exposure risks can be found in relation to the area of contamination. Three zones of contamination are outlined in the recommendations, with the red zone being the area of most significant contamination and the green zone being the area of lowest contamination. Level A OSHA protection is usually recommended in a red zone. Yellow zone area of contamination PPE needs should be decided with consideration for air monitoring results, skin contact risk, and proximity of the event. Green zone contamination with CBRN agents is unlikely to occur.

OSHA Defined PPE

- Level A: positive pressure full face-piece SCBA, encapsulating covering chemical protective suit, chemical-resistant outer gloves, chemical-resistant inner gloves, chemical-resistant boots with steel toe, disposable protective suit/gloves/boots

- Level B: positive pressure full face-piece SCBA, chemical-resistant clothes with hood, chemical-resistant outer gloves, chemical-resistant inner gloves, chemical-resistant boots with steel toe

- Level C: air purifying respirator, chemical-resistant clothes with hood, chemical-resistant outer gloves, chemical-resistant inner gloves, chemical-resistant boots with steel toe

- Level D: gloves, coveralls, chemical-resistant boots/shoes with steel toe, safety glasses or chemical splash goggles

Radiologic PPE

Exposure to ionizing radiation can present a significant long-term health risk to healthcare providers. PPE should be available for healthcare providers working within radiation-exposure settings. Of particular importance, dose reduction with exposure to x-ray and gamma radiation can be achieved with proper PPE.[37][38][39] Providers practicing with X-ray and gamma radiation exposure, especially fluoroscopy and other image-guided procedure devices, should have access to a lead apron/vest, lead-lined glasses, lead-lined cap, and lead protection collar.[40][41][42][43]

Dose monitoring is required by OSHA Ionizing Radiation standards for workers who enter a high radiation area or restricted area or receive a dose in any calendar quarter more than 25% of the appropriate occupational limit.[44][45][46][47] OSHA standards for monitoring radiation exposure can be followed by wearing a person's passive dosimeter for exposure dose evaluation.[48][49]

Clinical Significance

Personal protective equipment implementation has become the standard of care for medical providers. The COVID-19 pandemic reshaped healthcare in many ways, including the increased emphasis on health practitioner safety in the presence of communicable diseases. PPE has been shown to prevent the spread of disease and preserve the health of individual practitioners. Following guidelines regarding the use of PPE sets a standard for all healthcare organizations to follow. Proper training is needed for PPE to be effective, including the appropriate application and removal of PPE.

Specific steps for putting on (donning) and taking off (doffing) pieces of PPE will be reviewed here. Not all components of PPE are required for each patient, and specific isolation precautions should be followed as appropriate.[50][51][52]

Suggested Sequence for Application of PPE

Donning of PPE should take place outside patient rooms.

- Gown

- Cover body from neck to knees, arms to wrists, and ensure gown wraps around the back

- Tie neck and waist straps if available

- Mask or Respirator

- Place straps or ties around the head/neck

- Adjust the flexible band to the nose bridge for proper fit

- Fit-check respirator

- Eye protection

- Place eye protection on the face to ensure adequate protection of the face/eyes

- May include goggles and/or a face shield

- Gloves

- Ensure application of gloves extends to cover the wrist of the gown

Suggested Sequence for Removal of PPE

Doffing of PPE should take place outside patient rooms. If a respirator is in use, do not remove the respirator until after exiting the patient room.

- Gloves

- Remove the first glove by grasping the palmar surface with the other gloved hand, and discard the first glove in the appropriate disposal container

- Remove the second glove by sliding the fingers of the ungloved hand under the remaining glove at the wrist, and discard the second glove in the appropriate disposal container

- Eye protection

- Remove without touching the contaminated outside surface on the front of eye protection, and handle equipment by the strap or earpieces

- Dispose of in the appropriate reprocessing or waste container

- Gown

- Release gown straps or ties

- Touching inside of gown only, remove by pulling away from neck and shoulders

- Turn the gown inside out

- Place in an appropriate disposal container

- Mask or Respirator

- Do not touch the front or mouth area of the mask/respirator

- Remove by releasing ties or straps around the back of the head

- Discard in the appropriate disposal container

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Proper use of CDC and OSHA-recommended PPE within a healthcare setting prevents the spread of infectious pathogens between patients and providers. However, more expansive studies are needed to review current practices and policies.[53][54][55][56]

PPE also serves to help healthcare workers avoid harmful outcomes in the setting of exposure to CBRN agents. Adherence to PPE standards is multifaceted, with several components factoring into healthcare workers' ability and desire to follow PPE guidelines. Areas of concern include workplace culture, availability of PPE, training, trust in PPE, and communication of hospital guidelines.[57]

Administrative teams are often responsible for ensuring the availability of PPE resources. Infection prevention teams that monitor and track hospital personal standard precaution use may increase compliance.[58][59] [Level 2] Following suggested doffing protocols can decrease the risk of potential contamination after providing care.[60][61] [Level 2]

PPE has been shown to offer protection against respiratory infections, especially COVID-19.[62] [Level 1]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Verbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S, Sauni R, Toomey E, Blackwood B, Tikka C, Ruotsalainen JH, Kilinc Balci FS. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Emergencias : revista de la Sociedad Espanola de Medicina de Emergencias. 2021 Feb:33(1):59-61 [PubMed PMID: 33496400]

Edlich RF, Wind TC, Heather CL, Thacker JG. Reliability and performance of innovative surgical double-glove hole puncture indication systems. Journal of long-term effects of medical implants. 2003:13(2):69-83 [PubMed PMID: 14510280]

Guo YP, Wong PM, Li Y, Or PP. Is double-gloving really protective? A comparison between the glove perforation rate among perioperative nurses with single and double gloves during surgery. American journal of surgery. 2012 Aug:204(2):210-5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.017. Epub 2012 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 22342011]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEdlich R,Wind TC,Heather CL,Thacker JG, An Update on the Innovative Surgical Double-Glove Hole Puncture Indication Systems: Reliability and Performance. Journal of long-term effects of medical implants. 2017; [PubMed PMID: 29773048]

Kahveci Z, Kilinc-Balci FS, Yorio PL. Barrier resistance of double layer isolation gowns. American journal of infection control. 2021 Apr:49(4):430-433. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.09.017. Epub 2020 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 33080362]

Pissiotis CA, Komborozos V, Papoutsi C, Skrekas G. Factors that influence the effectiveness of surgical gowns in the operating theatre. The European journal of surgery = Acta chirurgica. 1997 Aug:163(8):597-604 [PubMed PMID: 9298912]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLankester BJ, Bartlett GE, Garneti N, Blom AW, Bowker KE, Bannister GC. Direct measurement of bacterial penetration through surgical gowns: a new method. The Journal of hospital infection. 2002 Apr:50(4):281-5 [PubMed PMID: 12014901]

Offeddu V, Yung CF, Low MSF, Tam CC. Effectiveness of Masks and Respirators Against Respiratory Infections in Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017 Nov 13:65(11):1934-1942. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix681. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29140516]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSu WC, Lee J, Xi J, Zhang K. Investigation of Mask Efficiency for Loose-Fitting Masks against Ultrafine Particles and Effect on Airway Deposition Efficiency. Aerosol and air quality research. 2022 Jan:22(1):. pii: 210228. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.210228. Epub 2021 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 35937716]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAndrews AS, Kiederer M, Casey ML. Understanding Filtering Facepiece Respirators. The American journal of nursing. 2022 Feb 1:122(2):21-23. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000820540.36250.bf. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35085143]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOberg T, Brosseau LM. Surgical mask filter and fit performance. American journal of infection control. 2008 May:36(4):276-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.07.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18455048]

Howard J, Huang A, Li Z, Tufekci Z, Zdimal V, van der Westhuizen HM, von Delft A, Price A, Fridman L, Tang LH, Tang V, Watson GL, Bax CE, Shaikh R, Questier F, Hernandez D, Chu LF, Ramirez CM, Rimoin AW. An evidence review of face masks against COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2021 Jan 26:118(4):. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014564118. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33431650]

Roberts V. To PAPR or not to PAPR? Canadian journal of respiratory therapy : CJRT = Revue canadienne de la therapie respiratoire : RCTR. 2014 Fall:50(3):87-90 [PubMed PMID: 26078617]

Licina A,Silvers A, Use of powered air-purifying respirator(PAPR) as part of protective equipment against SARS-CoV-2-a narrative review and critical appraisal of evidence. American journal of infection control. 2021 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 33186678]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDardas AZ, Serra Lopez VM, Boden LM, Gittings DJ, Heym K, Koerber E, Grosh T, Ahn J. A simple surgical mask modification to pass N95 respirator-equivalent fit testing standards during the COVID-19 pandemic. PloS one. 2022:17(8):e0272834. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0272834. Epub 2022 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 36001554]

Radonovich LJ Jr, Simberkoff MS, Bessesen MT, Brown AC, Cummings DAT, Gaydos CA, Los JG, Krosche AE, Gibert CL, Gorse GJ, Nyquist AC, Reich NG, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Price CS, Perl TM, ResPECT investigators. N95 Respirators vs Medical Masks for Preventing Influenza Among Health Care Personnel: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019 Sep 3:322(9):824-833. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11645. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31479137]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGarner JS. Guideline for isolation precautions in hospitals. The Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 1996 Jan:17(1):53-80 [PubMed PMID: 8789689]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWhitehouse JD, Sexton DJ, Kirkland KB. Infection control: past, present, and future issues. Comprehensive therapy. 1998 Feb:24(2):71-7 [PubMed PMID: 9533987]

Moralejo D, El Dib R, Prata RA, Barretti P, Corrêa I. Improving adherence to Standard Precautions for the control of health care-associated infections. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018 Feb 26:2(2):CD010768. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010768.pub2. Epub 2018 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 29481693]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTaylor E, Card AJ, Piatkowski M. Single-Occupancy Patient Rooms: A Systematic Review of the Literature Since 2006. HERD. 2018 Jan:11(1):85-100. doi: 10.1177/1937586718755110. Epub 2018 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 29448834]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceReilly JS, Price L, Lang S, Robertson C, Cheater F, Skinner K, Chow A. A Pragmatic Randomized Controlled Trial of 6-Step vs 3-Step Hand Hygiene Technique in Acute Hospital Care in the United Kingdom. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2016 Jun:37(6):661-6. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.51. Epub 2016 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 27050843]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFuller C, Savage J, Besser S, Hayward A, Cookson B, Cooper B, Stone S. "The dirty hand in the latex glove": a study of hand hygiene compliance when gloves are worn. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2011 Dec:32(12):1194-9. doi: 10.1086/662619. Epub 2011 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 22080658]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDoebbeling BN, Pfaller MA, Houston AK, Wenzel RP. Removal of nosocomial pathogens from the contaminated glove. Implications for glove reuse and handwashing. Annals of internal medicine. 1988 Sep 1:109(5):394-8 [PubMed PMID: 3136685]

Link T. Guideline Implementation: Transmission-Based Precautions. AORN journal. 2019 Dec:110(6):637-649. doi: 10.1002/aorn.12867. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31774162]

Spruce L. Transmission-Based Precautions. AORN journal. 2020 Nov:112(5):558-566. doi: 10.1002/aorn.13237. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33113203]

Ather B, Mirza TM, Edemekong PF. Airborne Precautions. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285363]

Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. American journal of infection control. 2007 Dec:35(10 Suppl 2):S65-164 [PubMed PMID: 18068815]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVerbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S, Sauni R, Toomey E, Blackwood B, Tikka C, Ruotsalainen JH, Kilinc Balci FS. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2020 May 15:5(5):CD011621. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011621.pub5. Epub 2020 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 32412096]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMuto CA, Jernigan JA, Ostrowsky BE, Richet HM, Jarvis WR, Boyce JM, Farr BM, SHEA. SHEA guideline for preventing nosocomial transmission of multidrug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus and enterococcus. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2003 May:24(5):362-86 [PubMed PMID: 12785411]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHick JL, Hanfling D, Burstein JL, Markham J, Macintyre AG, Barbera JA. Protective equipment for health care facility decontamination personnel: regulations, risks, and recommendations. Annals of emergency medicine. 2003 Sep:42(3):370-80 [PubMed PMID: 12944890]

Borron SW. Checklists for hazardous materials emergency preparedness. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2015 Feb:33(1):213-32. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2014.09.013. Epub 2014 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 25455670]

Borron SW. Introduction: Hazardous materials and radiologic/nuclear incidents: lessons learned? Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2015 Feb:33(1):1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2014.09.003. Epub 2014 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 25455659]

Coates MJ, Jundi AS, James MR. Chemical protective clothing; a study into the ability of staff to perform lifesaving procedures. Journal of accident & emergency medicine. 2000 Mar:17(2):115-8 [PubMed PMID: 10718233]

Holland MG, Cawthon D. Personal protective equipment and decontamination of adults and children. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2015 Feb:33(1):51-68. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2014.09.006. Epub 2014 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 25455662]

Johnston GM, Wills BK. Chemical Decontamination. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30844188]

Kako M, Hammad K, Mitani S, Arbon P. Existing Approaches to Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear (CBRN) Education and Training for Health Professionals: Findings from an Integrative Literature Review. Prehospital and disaster medicine. 2018 Apr:33(2):182-190. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X18000043. Epub 2018 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 29455699]

Durán A. [Radiation protection in interventional cardiology]. Archivos de cardiologia de Mexico. 2015 Jul-Sep:85(3):230-7. doi: 10.1016/j.acmx.2015.05.005. Epub 2015 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 26169040]

Durán A, Hian SK, Miller DL, Le Heron J, Padovani R, Vano E. Recommendations for occupational radiation protection in interventional cardiology. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2013 Jul 1:82(1):29-42. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24694. Epub 2013 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 23475846]

Bushong SC, Morin RL. Radiation safety. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2004 Feb:1(2):144-5 [PubMed PMID: 17411545]

Planz V, Huang J, Galgano SJ, Brook OR, Fananapazir G. Variability in personal protective equipment in cross-sectional interventional abdominal radiology practices. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2022 Mar:47(3):1167-1176. doi: 10.1007/s00261-021-03406-z. Epub 2022 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 35013750]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMayer MN,Koehncke NK,Belotta AF,Cheveldae IT,Waldner CL, Use of personal protective equipment in a radiology room at a veterinary teaching hospital. Veterinary radiology [PubMed PMID: 29230889]

Colangelo JE, Johnston J, Killion JB, Wright DL. Radiation biology and protection. Radiologic technology. 2009 May-Jun:80(5):421-41 [PubMed PMID: 19457846]

Kuon E, Birkel J, Schmitt M, Dahm JB. Radiation exposure benefit of a lead cap in invasive cardiology. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2003 Oct:89(10):1205-10 [PubMed PMID: 12975420]

Matsuzaki S, Moritake T, Sun L, Morota K, Nagamoto K, Nakagami K, Kuriyama T, Hitomi G, Kajiki S, Kunugita N. The Effect of Pre-Operative Verbal Confirmation for Interventional Radiology Physicians on Their Use of Personal Dosimeters and Personal Protective Equipment. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2022 Dec 15:19(24):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192416825. Epub 2022 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 36554706]

Rose A,Uebel K,Rae WID, Personal dosimeter utilisation among South African interventionalists. Journal of radiological protection : official journal of the Society for Radiological Protection. 2021 Jun 1; [PubMed PMID: 33873176]

Qureshi F, Ramprasad A, Derylo B. Radiation Monitoring Using Personal Dosimeter Devices in Terms of Long-Term Compliance and Creating a Culture of Safety. Cureus. 2022 Aug:14(8):e27999. doi: 10.7759/cureus.27999. Epub 2022 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 36134041]

Frye S, Reynolds AM, Botkin C, Muzaffar R, Osman MM. Monitoring Individual Occupational Radiation Exposure at Multiple Institutions. Journal of nuclear medicine technology. 2021 Nov 8:():. pii: jnmt.120.243154. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.120.243154. Epub 2021 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 34750239]

Hassan M, Patil A, Channel J, Khan F, Knight J, Loos M, Hazard H, Schaefer G, Wilson A. Do we glow? Evaluation of trauma team work habits and radiation exposure. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2012 Sep:73(3):605-11. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318265c9fa. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22929491]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRose A,Rae WID, Personal Protective Equipment Availability and Utilization Among Interventionalists. Safety and health at work. 2019 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 31297278]

Hegde S. Which type of personal protective equipment (PPE) and which method of donning or doffing PPE carries the least risk of infection for healthcare workers? Evidence-based dentistry. 2020 Jun:21(2):74-76. doi: 10.1038/s41432-020-0097-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32591668]

Mulvey D, Mayer J, Visnovsky L, Samore M, Drews F. Frequent and unexpected deviations from personal protective equipment guidelines increase contamination risks. American journal of infection control. 2019 Sep:47(9):1146-1147. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2019.03.013. Epub 2019 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 31027940]

Verbeek JH, Rajamaki B, Ijaz S, Sauni R, Toomey E, Blackwood B, Tikka C, Ruotsalainen JH, Kilinc Balci FS. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2020 Apr 15:4(4):CD011621. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011621.pub4. Epub 2020 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 32293717]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrown L,Munro J,Rogers S, Use of personal protective equipment in nursing practice. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain) : 1987). 2019 Apr 26; [PubMed PMID: 31468815]

Wilson J, Prieto J. Re-visiting contact precautions - 25 years on. Journal of infection prevention. 2021 Nov:22(6):242-244. doi: 10.1177/17571774211059988. Epub 2021 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 34880945]

Tschudin-Sutter S, Lucet JC, Mutters NT, Tacconelli E, Zahar JR, Harbarth S. Contact Precautions for Preventing Nosocomial Transmission of Extended-Spectrum β Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli: A Point/Counterpoint Review. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017 Jul 15:65(2):342-347. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix258. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28379311]

Kullar R, Vassallo A, Turkel S, Chopra T, Kaye KS, Dhar S. Degowning the controversies of contact precautions for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A review. American journal of infection control. 2016 Jan 1:44(1):97-103. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.08.003. Epub 2015 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 26375351]

Barratt R, Gilbert GL. Education and training in infection prevention and control: Exploring support for national standards. Infection, disease & health. 2021 May:26(2):139-144. doi: 10.1016/j.idh.2020.12.002. Epub 2021 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 33461891]

Thandar MM, Matsuoka S, Rahman O, Ota E, Baba T. Infection control teams for reducing healthcare-associated infections in hospitals and other healthcare settings: a protocol for systematic review. BMJ open. 2021 Mar 5:11(3):e044971. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044971. Epub 2021 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 33674376]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceThandar MM, Rahman MO, Haruyama R, Matsuoka S, Okawa S, Moriyama J, Yokobori Y, Matsubara C, Nagai M, Ota E, Baba T. Effectiveness of Infection Control Teams in Reducing Healthcare-Associated Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2022 Dec 19:19(24):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192417075. Epub 2022 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 36554953]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVerbeek JH,Ijaz S,Mischke C,Ruotsalainen JH,Mäkelä E,Neuvonen K,Edmond MB,Sauni R,Kilinc Balci FS,Mihalache RC, Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016 Apr 19; [PubMed PMID: 27093058]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSanford J, Holdsworth J. PPE training and the effectiveness of universal masking in preventing exposures: The importance of the relationship between anesthesia and infection prevention. American journal of infection control. 2021 Oct:49(10):1322-1323. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2021.05.003. Epub 2021 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 34022296]

Schoberer D, Osmancevic S, Reiter L, Thonhofer N, Hoedl M. Rapid review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of personal protective equipment for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public health in practice (Oxford, England). 2022 Dec:4():100280. doi: 10.1016/j.puhip.2022.100280. Epub 2022 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 35722539]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence