Glenolabral Articular Disruption (GLAD)

Glenolabral Articular Disruption (GLAD)

Introduction

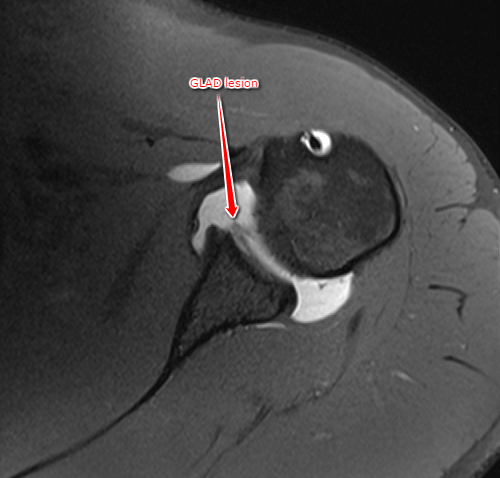

A glenolabral articular disruption (GLAD) lesion is a specific sub-type of a soft tissue shoulder injury (see Image. Magnetic Resonance Angiography, Axial GLAD Lesion). It involves a combination of a superficial tear to the anterior-inferior labrum and damage to the adjacent articular cartilage on the glenoid. The labrum is the fibrocartilaginous ring surrounding the glenoid fossa.

The GLAD superficial labral tear pattern, with the deep fibers still intact, means that the labrum is not grossly unstable. Therefore pain rather than frank instability symptoms should be present. The extent and type of underlying damage to the glenoid cartilage vary; it can be anything from more minor fibrillation to complete cartilage loss.

Since Neviaser first reported it as a limited series in 1993, it is now recognized as an uncommon but well-established cause of shoulder pain following trauma. The original observations were that the mechanism usually involves a fall with forced adduction movement to the abducted and externally rotated shoulder, but two cases were related to throwing activities.[1] There may also be a subluxation or dislocation injury associated.[2] Since Neviaser reported the original series, it is apparent that sometimes the term may be used more loosely to describe any combined labral pathology and adjacent articular cartilage lesion.

Clinical examination findings may be non-specific, including anteriorly sited or generalized shoulder pain during abduction and external rotation of the joint. Historically, GLAD lesions have been identified as being associated with a stable glenohumeral joint. As such, patients would reportedly display a full range of movement on examination without evidence of apprehension or subluxation.[1]

More recently, however, several reports have described GLAD lesions in the context of either isolated or recurrent dislocations, and thus the stability of the joint is not necessarily regarded as a distinguishing examination finding.[2] The indistinct findings on examination make a clinical diagnosis of the lesion challenging, and imaging is required to confirm its presence.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

GLAD lesions occur as a result of trauma to the shoulder joint. The classic pattern from the original series involves forced shoulder adduction from a position of abduction and external rotation. Typically this occurred in the context of a fall onto the outstretched arm. The humeral head being forced into the glenoid and then continuing to move with a shear force damaging the cartilage, with the energy of the injury finally tearing the superficial labral fibers, would fit with that mechanism.[3] However, the injury has also been linked to forceful adduction from throwing, clearly a slightly different mechanism.[1]

In modern practice, the use of MRI, MRI arthrography (MRA), and arthroscopy to evaluate shoulder injury has increased recognition of this injury. As such, the associated types of injury mechanisms have grown, and anterior glenohumeral instability is now a recognized injury mechanism.[2][4][5]

Epidemiology

Despite their status as a described glenolabral pathology, the epidemiological data on GLAD lesions is poor. The literature has primarily cited sporadic case reports or small series detailing clinical evaluation and repair techniques rather than reporting more extensive data analyses.[2] The consensus is that GLAD lesions are a rare occurrence. Glenohumeral labral tears overall are common, most are anterior-inferior, and inferior tears in isolation are less common.[6]

GLAD lesions have been estimated to occur in 1.5 to 2.9% of cases of traumatic labral tears. [4] Demographically, case reports generally involve younger males, in keeping with general traumatic labral pathology, although no specific age or gender trends have been reported.

Pathophysiology

GLAD lesions disrupt the labrum and the underlying glenoid cartilage within the glenohumeral (GH) joint. The GH joint itself is formed by the articulation of the humeral head within the glenoid fossa of the scapula, a synovial ball and socket joint. The fossa is lined by articular cartilage and surrounded at its margin by a fibrocartilaginous rim: the labrum.[7] The labrum provides additional depth to the fossa and an anchoring point for both the long head of the biceps tendon and the GH ligaments.[8]

The anteroinferior GH ligament and anteroinferior labrum together form the anterior labroligamentous complex. This provides an important restraint to anterior dislocation and is considered the most essential soft tissue structure in maintaining anterior shoulder stability.[3]

GLAD lesions typically arise when the humeral head impacts the glenoid fossa due to forceful adduction. There may be a shear force in addition. This causes a superficial tear to the labrum along its anterior-inferior aspect and a variable degree of underlying cartilage damage. This may include a focal cartilage defect, a more substantial flap tear, or even a loose chondral body.[8]

Classically, the integrity of the anterior labroligamentous complex is preserved, which explains why the shoulder joint remains stable in these cases.[3] However, the literature now recognizes the association between GLAD lesions and anterior shoulder instability.[2][4][5][9][10][11][12]

History and Physical

As in any shoulder trauma presentation, a thorough and targeted history, followed by examination including neurovascular assessment and special tests, should be performed on initial review. Often clinical history and examination findings are vague, and isolating the presence of a GLAD based on clinical suspicion alone is difficult.[1] However, these are typically higher energy injuries in younger male patients with what should be a clear onset of pain, potentially anteriorly though perhaps more diffusely, after that event. GLAD lesions may result from a fall onto an outstretched arm and classically include an adduction force onto an abducted and externally rotated shoulder.[1]

Therefore the position of the arm at injury and the direction of impact may provide some indication that a GLAD lesion may be present. However, it may simply be that pain persists following a traumatic instability episode, including a subluxation or dislocation.

On examination, pain may be elicited on abduction and external rotation, while forced adduction may produce a ‘popping’ sensation. The patient may localize to deep-seated anterior joint pain. Typically, the above findings are observed in the context of a stable shoulder joint, as normally, the anterior labroligamentous complex remains intact (it is only the superficial labral fibers that are damaged). In more recent studies, however, an association between GLAD lesions and anterior shoulder instability has also been recognized.[11][13][14]

In any case, the non-specific nature of the clinical characteristics makes evaluation with imaging essential for diagnosis.

Evaluation

Evaluation with imaging forms the hallmark of diagnosis of the GLAD lesion and should be performed early when clinical suspicion is raised. Lesions may be more difficult to detect on non-contrast MRI or CT arthrography imaging, but the newer 3T MRI scanners may improve the pick-up rate without contrast.[1] MR Arthrography (MRA) is the recognized gold standard to detect or define the GLAD lesion.[3][8][15]

The pathognomonic finding of the GLAD lesion is a superficial tear to the anterior-inferior labrum with an associated underlying glenoid cartilage defect. The cartilage defect may range from being superficial in depth to a trans-chondral defect exposing subchondral bone. This is demonstrated well on MRA, as contrast is observed tracking the labral tear and filling into the chondral defect or tracks under a damaged articular flap. It is described that the scan should ideally be performed with the shoulder in abduction and external rotation of patient mobility allows, as this significantly enhances both accuracy and sensitivity in detecting anterior labral tears of the shoulder.[8]

This positioning is not necessarily standard for investigating the more common anterior-inferior labral tears and will likely reflect individual unit protocols and the index of suspicion pre-imaging.

Treatment / Management

Both operative and non-operative care have been described and should be considered case-by-case. Preferences for either option will depend on individual factors, including expectations, time frame since the injury, level of symptoms, functional demands, and response to treatment to date.[16] Although we recognize that the GLAD lesion epidemiological data is limited, realistically, this injury concerns a younger demographic of patients with a higher energy sporting or traumatic injury pattern.

In the typical younger active patient, there needs to be a recognition that we do not know enough about this condition to understand how likely a trial of non-operative treatment will be successful. Time, analgesia, and physical therapy may treat a proportion of patients. However, operative intervention is an option to improve the glenoid articular surface and labral injury. It becomes especially relevant if patients do not improve with a trial of non-operative management or have too much pain to engage with that adequately.[4](B3)

It is known that there is an increase in incidental findings on the imaging of older patients, and clinicians should be more cautious of making this diagnosis in such patients; cartilage and labral degeneration are common with increasing age, and even if there is a traumatic event at the onset the emphasis would be a non-invasive approach with analgesia and physiotherapy - controlling pain and optimizing function.

An established arthroscopic approach will include the treatment of the labral and chondral pathology. The labral surgery may be a debridement of any unstable labral fibers, though any substantive partial tear might be suitable for stabilization. The chondral defect debridement removes loose chondral material and may involve the microfracture of any exposed glenoid bone. The definitive procedure will often depend on the size of the chondral defect encountered or, indeed, the combination of labral and chondral injury. Sometimes a full-thickness glenoid cartilage defect may be debrided, and the labrum advanced over it to cover the defect. If the defect is too large, only the articular surface is debrided, and the labrum is left in situ.[4][16](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The vague presenting features of GLAD lesions, and their association with both unstable and stable shoulder injuries, means that a broad differential diagnosis should be considered. This should include any traumatic glenolabral pathology causing either anterior or global shoulder discomfort. Such lesions may consist of:

- Common traumatic labral tears, tearing of the labrum and associated ligaments partially or completely off the glenoid, most commonly the anterior-inferior labrum (Bankart lesions)[17]

- Anterior-Inferior instability lesions that include a glenoid rim fracture - bony Bankart lesions [17]

- Perthes lesion – a labral complex injury, but the labrum is still attached to the glenoid via a periosteal sleeve [18]

- Anterior Ligamentous Periosteal Sleeve Avulsion – another labral injury, but it displaces medially on the glenoid neck [18]

- (HAGL) or Bony HAGL – this time, the anterior-inferior glenohumeral ligament is avulsed from the humeral rather than labral attachment [19]

Prognosis

Due to their relative infrequency, data on the prognosis of GLAD lesions are scarce, so it is difficult to be confident on this topic. When the lesion was originally reported in 1993, all five cases could return to full functional activities with a full range of movement post-operatively.[1]

Other case reports also support this outcome, suggesting excellent results following operative treatment of GLAD lesions when assessed by both pain and function.[4][5] A more rigorous level of outcome assessment is still required to affirm these clinical opinions, and hopefully, increasing knowledge will allow better-informed care decision-making.

Complications

As mentioned, research seems to suggest that GLAD lesions can be linked to episodes of anterior shoulder instability. One study, for example, identified that GLAD lesions were associated with higher rates of failure in arthroscopic Bankart repair.[20]

Another study demonstrated a correlation between GLAD lesions and reduced glenohumeral stability on a cohort of cadaveric shoulders – suggesting that the lesion may represent a biomechanical risk factor in shoulder instability. One hypothesis is that the GLAD lesion reduces the depth of the normal joint concavity, already limited, and therefore compromises concavity-compression and hence stability within the glenoid fossa.[21]

It has also been postulated that patients may be at risk of osteoarthritis (OA) following a GLAD injury. This hypothesis is based on trends seen following labral repair within hip surgery and knee meniscectomy - and the analogous anatomy and physiology between these three joints.[22][23]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Post-operative care is centered around physiotherapy to regain and optimize function, and a specialist physiotherapist should be consulted to oversee this process. It will depend on the surgery performed (repair vs. debridement, microfracture or not). If there is a labral repair, care will typically follow a conventional arthroscopic instability repair rehabilitation pathway.[5]

An example of such a program would involve: a sling for four weeks with elbow, wrist, and hand exercises, plus shoulder pendular movements during this time to reduce stiffness. Following this, a progressive exercise regime is adopted, starting with gentle active movements. This should progress over 6 to 8 weeks, ultimately encouraging an active range of movement, rotation, stretching, and controlled (light) strengthening work. At the end of this period, more significant strength conditioning work can be introduced progressively. In the athlete, return to non-contact and contact sport may occur at five and six months, respectively, as a guide, but that is based on hitting the relevant functional recovery milestones.[6]

Deterrence and Patient Education

At the time of diagnosis, it can be helpful to explain the pathoanatomy of the GLAD lesion with the help of models and diagrams. Under specialist supervision, good patient engagement will help their rehabilitation and recovery progress.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The evolution of imaging techniques has revolutionized the clinician’s ability to diagnose specific glenolabral pathology, including GLAD lesions. Consequently, several different glenolabral pathologies have been identified, each of which may be associated with persistent post-traumatic shoulder pain.

Gleno-labral injuries often have a similar clinical presentation, and the differences between some of the recognized sub-types can be subtle. Imaging also has some limitations and does not guarantee the identification of all such lesions. Even for shoulder experts, the diagnosis and management of persistent post-traumatic shoulder pain can pose clinical challenges.[3]

An interprofessional team of clinicians (MDs, DOs, NPs, or PAs), specialists (primarily orthopedists and radiologists), nursing staff, and physical therapists best serves optimum patient management. If the patient initially reports to their family clinician, prompt orthopedic referral and consultation by a shoulder specialist is paramount and should be encouraged with undiagnosed significant shoulder pain has persisted after injury. Nursing staff, particularly specialized orthopedic nurses, can assist in patient evaluation and referral. Nurses can also assist during surgery, post-operative care, and follow-up in cases where surgery is necessary. If a GLAD lesion or one of the alternative traumatic sub-type of injury patterns is suspected, the involvement of a musculoskeletal radiologist to facilitate an appropriate imaging modality, likely MR arthrography, is equally important.[8]

Once diagnosed and treated, a specialist physiotherapist should supervise the recovery period, whether or not a surgical approach is adopted. This interprofessional paradigm, with open communication between the various team members, will yield the best chances for patients to recover as much shoulder function as can be expected. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Neviaser TJ. The GLAD lesion: another cause of anterior shoulder pain. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 1993:9(1):22-3 [PubMed PMID: 8442825]

Porcellini G, Cecere AB, Giorgini A, Micheloni GM, Tarallo L. The GLAD Lesion: are the definition, diagnosis and treatment up to date? A Systematic Review. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis. 2020 Dec 30:91(14-S):e2020020. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i14-S.10987. Epub 2020 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 33559615]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSanders TG, Tirman PF, Linares R, Feller JF, Richardson R. The glenolabral articular disruption lesion: MR arthrography with arthroscopic correlation. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1999 Jan:172(1):171-5 [PubMed PMID: 9888763]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAgarwalla A,Puzzitiello RN,Leong NL,Forsythe B, Concurrent Primary Repair of a Glenoid Labrum Articular Disruption and a Bankart Lesion in an Adolescent: A Case Report of a Novel Technique. Case reports in orthopedics. 2019; [PubMed PMID: 30881714]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePage R, Bhatia DN. Arthroscopic repair of a chondrolabral lesion associated with anterior glenohumeral dislocation. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2010 Dec:18(12):1748-51. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1095-3. Epub 2010 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 20221586]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePage RS, Fraser-Moodie JA, Bayne G, Mow T, Lane S, Brown G, Gill SD. Arthroscopic repair of inferior glenoid labrum tears (Down Under lesions) produces similar outcomes to other glenoid tears. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2021 Dec:29(12):4015-4021. doi: 10.1007/s00167-021-06702-9. Epub 2021 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 34455449]

Chang LR, Anand P, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Glenohumeral Joint. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725703]

Robinson G,Ho Y,Finlay K,Friedman L,Harish S, Normal anatomy and common labral lesions at MR arthrography of the shoulder. Clinical radiology. 2006 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 16978976]

Galano GJ, Weisenthal BM, Altchek DW. Articular shear of the anterior-inferior quadrant of the glenoid: a glenolabral articular disruption lesion variant. American journal of orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.). 2013 Jan:42(1):41-3 [PubMed PMID: 23431540]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhu W, Lu W, Zhang L, Han Y, Ou Y, Peng L, Liu H, Wang D, Zeng Y. Arthroscopic findings in the recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder. European journal of orthopaedic surgery & traumatology : orthopedie traumatologie. 2014 Jul:24(5):699-705. doi: 10.1007/s00590-013-1259-1. Epub 2013 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 23812876]

Singh RB, Hunter JC, Smith KL. MRI of shoulder instability: state of the art. Current problems in diagnostic radiology. 2003 May-Jun:32(3):127-34 [PubMed PMID: 12783081]

Lederman ES,Flores S,Stevens C,Richardson D,Lund P, The Glenoid Labral Articular Teardrop Lesion: A Chondrolabral Injury With Distinct Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic [PubMed PMID: 29102569]

Antonio GE, Griffith JF, Yu AB, Yung PS, Chan KM, Ahuja AT. First-time shoulder dislocation: High prevalence of labral injury and age-related differences revealed by MR arthrography. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2007 Oct:26(4):983-91 [PubMed PMID: 17896393]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceO'Brien J, Grebenyuk J, Leith J, Forster BB. Frequency of glenoid chondral lesions on MR arthrography in patients with anterior shoulder instability. European journal of radiology. 2012 Nov:81(11):3461-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.05.013. Epub 2012 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 22698712]

Thomsen HS. Recent hot topics in contrast media. European radiology. 2011 Mar:21(3):492-5. doi: 10.1007/s00330-010-2026-x. Epub 2010 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 21136062]

Elser F,Braun S,Dewing CB,Millett PJ, Glenohumeral joint preservation: current options for managing articular cartilage lesions in young, active patients. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic [PubMed PMID: 20434669]

Tupe RN, Tiwari V. Anteroinferior Glenoid Labrum Lesion (Bankart Lesion). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 36508533]

Ladd LM, Crews M, Maertz NA. Glenohumeral Joint Instability: A Review of Anatomy, Clinical Presentation, and Imaging. Clinics in sports medicine. 2021 Oct:40(4):585-599. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2021.05.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34509200]

Liles JL, Fossum BW, Mologne M, Su CA, Godin JA. Treatment of the 'The Naked Humeral Head': Repair of Supraspinatus Avulsion, Subscapularis Tear, and Humeral Avulsion of the Glenohumeral Ligament. Arthroscopy techniques. 2022 Nov:11(11):e2103-e2111. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2022.08.010. Epub 2022 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 36457391]

Pogorzelski J,Fritz EM,Horan MP,Katthagen JC,Provencher MT,Millett PJ, Failure following arthroscopic Bankart repair for traumatic anteroinferior instability of the shoulder: is a glenoid labral articular disruption (GLAD) lesion a risk factor for recurrent instability? Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2018 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 29730139]

Wermers J, Schliemann B, Raschke MJ, Dyrna F, Heilmann LF, Michel PA, Katthagen JC. The Glenolabral Articular Disruption Lesion Is a Biomechanical Risk Factor for Recurrent Shoulder Instability. Arthroscopy, sports medicine, and rehabilitation. 2021 Dec:3(6):e1803-e1810. doi: 10.1016/j.asmr.2021.08.007. Epub 2021 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 34977634]

Harris JD. Hip labral repair: options and outcomes. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2016 Dec:9(4):361-367 [PubMed PMID: 27581790]

Englund M, Lohmander LS. Risk factors for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis fifteen to twenty-two years after meniscectomy. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2004 Sep:50(9):2811-9 [PubMed PMID: 15457449]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence