Introduction

Addison disease, also known as autoimmune adrenalitis, is an acquired primary adrenal insufficiency. Primary adrenal insufficiency is termed Addison disease when an autoimmune process causes the condition and is a rare but potentially life-threatening emergency condition. Addison disease results from the destruction of the bilateral adrenal cortex, leading to decreased adrenocortical hormones, including cortisol, aldosterone, and androgens. Addison disease's insidious course of action usually presents with glucocorticoid deficiency followed by mineralocorticoid. However, the condition can also present acutely, often triggered by intercurrent illness. The presentation of adrenal insufficiency depends on the rate and extent of adrenal function involvement. The most common cause of primary adrenal insufficiency is Addison disease, associated with increased levels of 21-hydroxylase antibodies.[1][2]

Addison disease usually manifests as an insidious and gradual onset of nonspecific symptoms, often resulting in a delayed diagnosis. The symptoms may worsen over a period, which makes early recognition difficult. A high clinical suspicion should be maintained to avoid misdiagnosis.[3] In many cases, the diagnosis is made only after the patient presents with an acute adrenal crisis manifesting with hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and hypoglycemia. The diagnosis is established by demonstrating low cortisol and aldosterone levels, high renin levels, and a blunt cortisol response with ACTH stimulation. Addison crisis is a severe endocrine emergency; immediate recognition and treatment are required. For stabilized patients diagnosed with Addison disease, life-long treatment with hormonal replacement is needed. Maintenance therapy aims to provide a replacement to maintain a physiologic glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid level.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Addison disease is caused by an inability of the adrenal cortices to produce adequate adrenocortical hormones. The condition is classified as primary or secondary adrenal insufficiency.[4]

Primary Adrenal Insufficiency

Any disease process that causes direct injury to the adrenal cortex can result in primary adrenal insufficiency (ie, Addison disease), including autoimmune, infectious, hemorrhagic, pharmacologic, and infiltrative etiologies.

Autoimmune

Autoimmune destruction of the adrenal glands is the most common cause of Addison's disease.[5] This destruction occurs as antibodies develop against the adrenal cortex.[6] Autoimmune destruction can be an isolated finding or type 1 and 2 autoimmune polyglandular endocrinopathies. Patients with autoimmune adrenal disease are more likely to have polyglandular autoimmune syndromes.[7][8][9]

- Type 1 autoimmune polyglandular syndrome is manifested by autoimmune polyendocrinopathy, candidiasis, and ectodermal dysplasia. The classic triad consists of hypoparathyroidism, Addison disease, and mucocutaneous candidiasis.

- Type 2 autoimmune polyglandular syndrome is associated with several conditions:

Infections

Infectious etiologies include sepsis, tuberculosis, cytomegalovirus, and HIV.[12] The prevalence of tuberculosis has declined, but HIV has emerged as the most important cause of adrenal insufficiency associated with adrenal necrosis.[13] Other infectious causes include disseminated fungal infections, histoplasmosis, and syphilis. Blastomycosis is another cause of Addison disease, particularly in South America.

Adrenal Hemorrhage

DIC, trauma, meningococcemia, and neoplastic processes can precipitate bilateral adrenal hemorrhages. An Adrenal crisis due to meningococcemia is known as the Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome and is more common in children and patients with asplenia.[14]

Infiltration

Adrenal infiltration frequently occurs with hemochromatosis, amyloidosis, and metastases. Other causes include sarcoidosis, lymphoma, and genetic disorders such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia and adrenal leukodystrophy.[15][16] Wolman disease is a rare inborn error of metabolism that presents with diarrhea, hepatosplenomegaly, failure to thrive, and calcification of adrenal glands.[17] Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome has been identified as a cause of adrenal insufficiency.[18]

Medications

Certain pharmacologic etiologies can lead to adrenal insufficiency by blocking cortisol synthesis. For instance, ketoconazole directly inhibits adrenal enzymes, and etomidate can have a dose-dependent effect by selectively inhibiting 11β-hydroxylase, decreasing deoxycortisol conversion to cortisol.[19][20][21]

Secondary Adrenal Insufficiency

Secondary insufficiency occurs most commonly due to exogenous steroid administration, resulting in the suppression of ACTH synthesis. Secondary adrenal insufficiency is a pituitary-dependent loss of ACTH secretion, which reduces glucocorticoid production. However, mineralocorticoid secretion, including aldosterone, remains relatively normal.[5] Secondary adrenal insufficiency is more common than primary insufficiency, with symptoms usually occurring after the discontinuation of a steroid.

- Primary: autoimmune-mediated intrinsic adrenal gland dysfunction, which leads to cortisol and aldosterone deficiency

- Secondary: chronic glucocorticoid administration resulting in hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction and cortisol deficiency alone.

Epidemiology

Addison's disease is rare, with an incidence of .6 per 100,000 of the population annually. The total number of people affected by this condition at a given time ranges from 4 to 11 per 100,000 of the population. In adults, the typical age of Addison disease presentation is 30 to 50 years and is more frequently seen in women. Risk factors for the autoimmune type of Addison's disease, which is the most common type, include other autoimmune conditions:

- Type I diabetes

- Hypoparathyroidism

- Hypopituitarism

- Pernicious anemia

- Graves' disease

- Chronic thyroiditis

- Dermatis herpetiformis

- Vitiligo

- Myasthenia gravis

Pathophysiology

Adrenal failure in Addison disease results in decreased cortisol production initially followed by that of aldosterone, both of which will eventually result in an elevation of adrenocorticotropic (ACTH) and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) hormones due to the loss of negative feedback inhibition.[22]

History and Physical

Addison disease usually manifests as an insidious and gradual onset of nonspecific symptoms, often resulting in a delayed diagnosis. The symptoms may worsen over a period, which makes early recognition difficult. A high clinical suspicion should be maintained to avoid misdiagnosis.[3] In many cases, the diagnosis is made only after the patient presents with an acute adrenal crisis manifesting with hypotension, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and hypoglycemia. This may be precipitated by a stressful illness or triggering factors such as infection, trauma, surgery, vomiting, or diarrhea.[23] Significant stress or disease can unmask cortisol and mineralocorticoid deficiency.

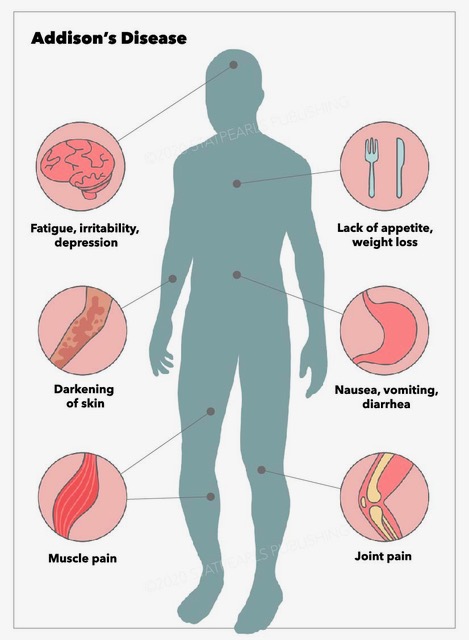

Addison disease can occur at any age but most often presents during the second or third decades of life. The initial presenting features include fatigue, generalized weakness, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dizziness, tachycardia, and hypotension. Clinicians should also assess for wasting of subcutaneous tissue. There may be declining health over several weeks or months.[24] Due to its variable presentation, a high index of suspicion for Addison disease is necessary when evaluating patients with nonspecific symptoms. These may include unexplained fatigue, poor appetite, chronic abdominal pain, or weight loss. Addisonian crisis is manifested by severe dehydration, confusion, refractory hypotension, and shock and is more likely to occur in primary adrenal insufficiency than secondary adrenal insufficiency.

Physical evaluation should include an examination of the skin and mucous membranes for hyperpigmentation. Hyperpigmentation of skin and mucous membranes, a hallmark of Addison disease, is usually generalized and most prominent in sun-exposed and pressure areas.[25] Specific sites should be carefully evaluated for hyperpigmentation, including the palmar creases, gingival mucosa, lips, particularly the vermilion border, elbows, knuckles, posterior neck, breast areola, nipples, and nail beds. Hyperpigmentation may appear as bronzing of the skin or diffuse darkening or dark patches and occurs in almost all patients with Addison disease.[26] However, there have been few reports of patients with adrenal insufficiency without hyperpigmentation. This may delay the diagnosis.[27] Also, hyperpigmentation is not seen in secondary insufficiency because ACTH and MSH levels are low. Elevated ACTH and melanocyte-stimulating hormone are causative factors and are believed to occur due to ACTH binding to the melanocyte receptors responsible for pigmentation. Furthermore, multiple new nevi may develop, and decreased or sparse axillary and pubic hair may occur in female patients. Vitiligo may also be observed.

Evaluation

Diagnostic Laboratory Studies

The diagnosis of Addison disease is established by demonstrating low cortisol and aldosterone levels, high renin levels, and a blunt cortisol response with ACTH stimulation. The following is the recommended diagnostic approach for the evaluation of Addison disease.

- An inappropriately low cortisol level [5]

- Assessing the adrenal cortex's functional capacity to synthesize cortisol and determine whether the cortisol deficiency is related to a corticotropin (ACTH) deficiency will help to classify whether the adrenal insufficiency is primary or secondary.

- Determining whether a treatable cause is present and performing further evaluation should be directed by its underlying cause.

Cortisol Level

A low random cortisol level is characteristically seen with Addison disease. Cortisol typically follows a diurnal pattern with the highest level in the early morning; therefore, an early morning level should be obtained. However, getting an early morning cortisol level in the emergency department (ED) is impractical. Furthermore, these results are not readily available during an ED visit. A single serum cortisol level determination is insufficient to assess adrenal function. However, a morning cortisol level >18 mcg/dL is a normal finding and may exclude an Addison disease diagnosis, while a low cortisol level of <3 mcg/dL is sufficient to diagnose adrenal insufficiency. The following is a summary of cortisol level interpretation.

- Normal cortisol level: morning cortisol of >18 mcg/dL = Normal

- Adrenal insufficiency: <3 mg/dL

- Equivocal; further evaluation recommended: 3 to 19 mcg/dL

ACTH Level and Corticotropin Stimulation Test

The ACTH level is markedly elevated in primary adrenal insufficiency. However, the level is not elevated or within the reference range in patients with central adrenal insufficiency. In equivocal cases, the diagnosis is confirmed by an ACTH (ie, cosyntropin) stimulation test, which causes rapid stimulation of cortisol and aldosterone secretion. An ACTH stimulation test is a first-line diagnostic test for evaluating adrenal insufficiency. Furthermore, plasma cortisol levels should be measured at 0 minutes and 30 to 60 minutes after the administration of ACTH. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) stimulates ACTH release from the pituitary. In primary adrenal insufficiency, a high ACTH level is present, which rises further after CRH stimulation; however, serum cortisol secretion cannot be stimulated. Conversely, a low ACTH level is seen in secondary adrenal insufficiency, failing to respond to CRH. The following is a summary of the interpretation of the ACTH stimulation test.

- Primary adrenal insufficiency: elevated ACTH

- Central adrenal insufficiency: abnormally normal or low ACTH

With ACTH stimulation

- Normal response: peak cortisol level >18 mcg/dL

- Adrenal insufficiency: <18 mcg/dL or no response [28]

Aldosterone and Renin Level

Serum renin and aldosterone levels should be obtained to determine whether a mineralocorticoid deficiency is present. Both cortisol and aldosterone are missing in primary adrenal insufficiency. A low aldosterone concentration is present despite markedly increased plasma renin activity. In secondary adrenal insufficiency, the aldosterone level will be normal. Increased plasma renin activity can be seen; this indicates that there is adrenal cortex dysfunction. A high level occurs when there is a low level of serum aldosterone.

Comprehensive Metabolic Panel

Laboratory findings that are characteristic of Addison disease include hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, and hypoglycemia. Hyponatremia is due to cortisol and aldosterone deficiency. Aldosterone deficiency causes sodium wasting, and cortisol decreases antidiuretic hormone, leading to increased water absorption. Hypovolemia also triggers ADH secretion. Hyperkalemia is secondary to low aldosterone levels, which causes natriuresis and potassium retention. However, hyperkalemia does not occur in secondary disease; this helps to distinguish it from primary adrenal insufficiency. Hypoglycemia is multifactorial, including decreased oral intake and lack of glucocorticoids, which are essential for gluconeogenesis. Hypercalcemia may be present, which reflects extracellular fluid loss.

Thyroid-stimulating Hormone

A slight elevation of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level can occur in adrenal insufficiency due to decreased cortisol levels and abnormal TSH circadian rhythm.[29] If TSH elevation persists, clinicians should consider the possibility of hypothyroidism.

Anti–21-hydroxylase Antibodies

Anti-adrenal antibodies (eg, 21-hydroxylase antibodies) are the markers of autoimmune destruction of the adrenal gland. The 21-hydroxylase enzyme is essential for cortisol synthesis in the adrenal cortex and can help determine an underlying cause in patients with clinical features of adrenal insufficiency. Anti-adrenal antibodies are also necessary to evaluate other organ-specific autoimmune conditions.

Diagnostic Imaging Studies

A biochemical diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency should be made before obtaining imaging studies, as radiographic findings are nonspecific. In patients with adrenal insufficiency, a chest radiograph may reveal a small heart, which may be due to a decrease in the cardiac workload. In suspected cases of adrenal hemorrhage, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan may provide helpful information in determining the cause. For example, bilateral enlargement of the adrenal glands may be seen with adrenal hemorrhage. Additionally, adrenal gland calcification or hemorrhage can be seen with tuberculosis.

Furthermore, a finding on imaging of small adrenal glands suggests autoimmune adrenal destruction. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the hypothalamic-pituitary region should be obtained if ACTH is inappropriately low in the presence of cortisol deficiency. A pituitary baseline profile should also be obtained.

Additional Diagnostic Studies

Additional studies should be directed to determine the underlying cause of adrenal insufficiency. A PPD test should be performed to evaluate for tuberculosis. A serum very long-chain fatty acid profile should be obtained in cases where adrenal leukodystrophy is suspected. Complete blood count (CBC) may reveal neutropenia, lymphocytosis, and eosinophilia. In patients with hyperkalemia, electrocardiograms (ECG) may show tall and peaked T waves. Histology examination is useful in investigating infiltrative causes of adrenal insufficiency. The finding of caseating granulomas may suggest tuberculosis, whereas a non-caseating granuloma may be due to sarcoidosis.[30][31]

Treatment / Management

Early recognition is critical for the management of acute adrenal insufficiency. Addison crisis is a severe endocrine emergency; immediate recognition and treatment are required. Addison crisis that is not promptly recognized and treated can be fatal. The confirmatory laboratory evaluation should not delay the treatment. Blood samples should be obtained for subsequent measurement of ACTH and cortisol levels. The elevation of ACTH with low cortisol is diagnostic of a primary adrenal insufficiency. Cortisol in the ACTH stimulation test may be measured when initial laboratory evaluation cannot establish the diagnosis. Plasma renin level is often elevated and indicates a mineralocorticoid deficiency, accompanied by a low aldosterone level.[32][33][34]

Acute Phase Therapy

The approach to patients with an adrenal crisis consists of the following components.

- Fluid resuscitation: to restore the intravascular volume with intravenous (IV) normal saline

- Dextrose: to correct hypoglycemia

- Correction of the hormone deficiency: both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid

Hydrocortisone should be immediately administered as the initial hormonal treatment. The recommended adult regimen for adrenal crisis is hydrocortisone 100 mg intravenous (IV) bolus initially, followed by 50 to 100 mg IV every 6 hours over 24 hours. In children, the dosage is 50 mg/m2 IV bolus with a maximum dose of 100 mg, followed by 50 to 100 mg/m2. Since this dose has significant mineralocorticoid activity, other mineralocorticoids (eg, fludrocortisone) are unnecessary during the acute phase.[35] Dexamethasone 4 mg IV bolus can be considered in the ED when emergent steroid administration is required, as dexamethasone is less likely to interfere with the serum cortisol assays. Dexamethasone is long-acting and does not interfere with biochemical assays of endogenous glucocorticoid production. Prednisone and dexamethasone have little or no mineralocorticoid activity. Initial fluid replacement with a normal saline bolus followed by 5% glucose in isotonic saline is also recommended. Hypoglycemia should be treated promptly.(B3)

Maintenance Phase Therapy

In patients with stabilized Addison disease, life-long treatment with hormonal replacement is required. Maintenance therapy aims to provide a replacement to maintain a physiologic glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid level. The usual dosage regimens are as follows:

- Glucocorticoid

- Hydrocortisone 5 to 25 mg/day divided into 2 or 3 doses

- Prednisone 3 to 5 mg/day

Doses should be adjusted according to the clinical response and normalization of electrolyte abnormalities. To minimize adverse effects, the dosage should be titrated to the lowest possible dose that controls symptoms; the patient should also be ensured to be clinically well. A plasma renin level can also be used to adjust the doses. Serum ACTH levels may vary significantly and cannot be used for dose adjustment. Clinicians should also consider a patient's concurrent medications when deciding the glucocorticoid dose. For example, certain drugs, such as rifampin, can increase hepatic glucocorticoid metabolism and may inactivate cortisol. Dexamethasone is not an appropriate choice for maintenance treatment as the dose titration is challenging and increases the risk of the Cushing effect.[36]

Fludrocortisone should be administered at a sufficient dose to keep the plasma renin level in the reference range.[37] An elevated PRA indicates a higher dose of fludrocortisone is required. The mineralocorticoid dosage should be tailored to address the degree of stress. Furthermore, identifying and treating underlying causes such as sepsis is critical for an optimal outcome. The treatment of associated conditions should also be provided.

- Mineralocorticoid

- Fludrocortisone .05 to .2 mg daily

- Hydrocortisone (in children) 8 mg/m2/day orally initially, divided into 3 or 4 doses.

Treatment Considerations

- In patients with Addison disease, glucocorticoid secretion does not increase during stress. Therefore, in the presence of fever, infection, or other illnesses, the hydrocortisone dose should be increased to compensate for a possible stress response.

- Generally, a usual hydrocortisone stress dose is 2 to 3 times the daily maintenance dose.[38]

- Patients taking rifampin require an increased dose of hydrocortisone, as rifampin increases the clearance of hydrocortisone.

- Thyroid hormone can increase the hepatic clearance of cortisol, precipitating an adrenal crisis. Glucocorticoid replacement can potentially normalize thyroid-stimulating hormone.

- In patients with concomitant diabetes insipidus, glucocorticoid therapy can aggravate diabetes insipidus. Cortisol is required for free-water clearance, and cortisol deficiency may prevent polyuria.

- Pregnancy, particularly during the third trimester, increases corticosteroid requirements.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of adrenal crisis includes most other conditions that can cause shock. The differential diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency is broad, including the following conditions.

- Sepsis: Many features of sepsis overlap with adrenal insufficiency. The presentation includes weakness, fatigue, vomiting, hypotension, and shock. The primary adrenal insufficiency diagnosis is confirmed by low cortisol response to ACTH stimulation test and low ACTH level.

- Shock: Any type of shock with a decreased serum cortisol level suggests adrenal insufficiency.

- Chronic fatigue syndrome: Chronic persisting or relapsing fatigue may mimic adrenal insufficiency. However, laboratory evaluations such as cortisol level after corticotropin stimulation differentiate it from adrenal insufficiency.

- Infectious mononucleosis: The presentation may be similar to fever, fatigue, and myalgias, which may occur in both conditions. However, exudative pharyngitis is present in this condition. IgM antibodies to viral capsid antigens are present.

- Hypothyroidism: As with adrenal insufficiency, fatigue may be present in hypothyroidism. However, hypothyroidism is associated with weight gain. The cortisol level differentiates both conditions.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

A delay in initiating the treatment can have severe consequences and may increase rates of morbidity and mortality.[39]

Prognosis

The treatment of Addison disease involves a life-long replacement of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. However, most patients live an active life. A strict balance is required to avoid over- or under-treatment with glucocorticoids. Therefore, careful monitoring is needed. Over-treatment with glucocorticoids may result in obesity, diabetes, and osteoporosis.[40] Over-treatment with mineralocorticoids can cause hypertension.

Up to 50% of patients with Addison disease may develop another autoimmune condition; therefore, continued clinical monitoring is recommended.[41] Thyroid hormone replacement before glucocorticoid administration may precipitate an adrenal crisis in unrecognized patients due to increased cortisol clearance. Rapid recognition and treatment are necessary in acute adrenal crisis.

Complications

Several complications can occur due to Addison disease or secondary to inappropriate treatment. Addison disease can progress to an adrenal crisis if not recognized and promptly treated, resulting in hypotension, shock, hypoglycemia, acute cardiovascular decompensation, and death. Patients with adrenal insufficiency are also at higher risk of death due to infections, cancer, and cardiovascular causes. Delayed recognition and treatment of hypoglycemia can cause serious consequences.[42] A supraphysiologic glucocorticoid replacement can lead to the development of Cushing syndrome.[39] Growth suppression can occur in children. Premature ovarian failure or primary ovarian insufficiency may develop in up to 10% of women with Addison disease.[43]

Consultations

The treatment plan should be developed in consultation with an endocrinologist. All patients with an adrenal crisis should be consulted with intensivists and admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU). Patients who are ill-appearing and present with shock should be admitted to ICU.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with Addison disease should receive education about the management and monitoring of their condition, including:

- Medication doses and compliance with the treatment plans, such as increasing steroid replacement doses in stressful situations such as fever, surgery, or stress

- Having an emergency medical alert bracelet

- Self-care, including adequate sodium intake in the diet, weight, and blood pressure monitoring

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to consider regarding Addison disease are as follows:

-

Idiopathic autoimmune adrenocortical insufficiency is the most common cause of Addison disease.

-

Symptoms of Addison disease can be nonspecific and, therefore, can be challenging to recognize. A high index of suspicion is required to make this diagnosis.

- Serum morning cortisol <3 mcg/dL with a simultaneous elevation of the plasma ACTH level >200 pg/mL establishes an Addison disease diagnosis.

-

Primary adrenal insufficiency diagnosis should be considered in acutely ill patients presenting volume depletion, hypotension, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia.

- Clinicians should consider the possibility of adrenal insufficiency in critically ill patients who failed to improve with resuscitation with fluid administration, particularly in the presence of hyperpigmentation, hyponatremia, or hyperkalemia.

- In an Addisonian crisis, treatment is a priority and should not be delayed for diagnostic confirmation; a delayed treatment can be fatal.

-

The treatment of choice for adrenal crisis is hydrocortisone; this has both glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid properties.

- Glucocorticoid doses should be increased in the presence of fever, infection, or other stresses.

- Titrate the glucocorticoid dose to the lowest possible dose, which can control symptoms and minimize the adverse effects.

- Thyroid hormone treatment can precipitate an adrenal crisis since the thyroid hormone can increase the hepatic clearance of cortisol.

- Serum cortisol, plasma ACTH, plasma aldosterone, and plasma renin levels should all be obtained before performing the ACTH stimulation test.

- Addison disease, due to autoimmune adrenalitis, can develop into another autoimmune disorder.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Addison disease is a life-threatening condition that requires accurate diagnosis and prompt treatment. A delayed diagnosis carries a high morbidity and mortality. Thus, the condition is best managed by an interprofessional team of healthcare workers, including an endocrinologist, an intensivist, an infectious disease specialist, and a pharmacist. The education of the patient is critical for patients with chronic conditions. Physicians, nurses, and pharmacists can share this responsibility. Nurses need to administer treatments, monitor patients, and provide updates to the team. Once the diagnosis is established, the outcomes depend on the primary cause. Any delay in initiating the treatment can lead to poor outcomes. All patients who have Addison disease must be urged to wear a medical alert bracelet. Patients should be educated regarding the signs and symptoms. They should be urged to contact their primary care provider if there are any warning symptoms. Finally, in times of stress, such as fever, patients should be instructed to double the dose of steroids and see their primary care provider.[44][32]

Media

References

Yamamoto T. Latent Adrenal Insufficiency: Concept, Clues to Detection, and Diagnosis. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2018 Aug:24(8):746-755. doi: 10.4158/EP-2018-0114. Epub 2018 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 30084678]

Choudhury S, Meeran K. Glucocorticoid replacement in Addison disease. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2018 Sep:14(9):562. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0049-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29930339]

Erichsen MM, Løvås K, Skinningsrud B, Wolff AB, Undlien DE, Svartberg J, Fougner KJ, Berg TJ, Bollerslev J, Mella B, Carlson JA, Erlich H, Husebye ES. Clinical, immunological, and genetic features of autoimmune primary adrenal insufficiency: observations from a Norwegian registry. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2009 Dec:94(12):4882-90. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1368. Epub 2009 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 19858318]

Bancos I, Hahner S, Tomlinson J, Arlt W. Diagnosis and management of adrenal insufficiency. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology. 2015 Mar:3(3):216-26. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70142-1. Epub 2014 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 25098712]

Charmandari E, Nicolaides NC, Chrousos GP. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet (London, England). 2014 Jun 21:383(9935):2152-67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61684-0. Epub 2014 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 24503135]

Bridwell RE, April MD. Adrenal Emergencies. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2023 Nov:41(4):795-808. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2023.06.006. Epub 2023 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 37758424]

Michels AW, Eisenbarth GS. Immunologic endocrine disorders. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2010 Feb:125(2 Suppl 2):S226-37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.053. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20176260]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFischli S. [CME: Adrenal Insufficiency]. Praxis. 2018 Jun:107(13):717-725. doi: 10.1024/1661-8157/a002982. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29921185]

Singh G, Jialal I. Polyglandular Autoimmune Syndrome Type II. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252248]

Conrad N, Misra S, Verbakel JY, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G, Taylor PN, Mason J, Sattar N, McMurray JJV, McInnes IB, Khunti K, Cambridge G. Incidence, prevalence, and co-occurrence of autoimmune disorders over time and by age, sex, and socioeconomic status: a population-based cohort study of 22 million individuals in the UK. Lancet (London, England). 2023 Jun 3:401(10391):1878-1890. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00457-9. Epub 2023 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 37156255]

Collin P, Kaukinen K, Välimäki M, Salmi J. Endocrinological disorders and celiac disease. Endocrine reviews. 2002 Aug:23(4):464-83 [PubMed PMID: 12202461]

Bachmeier CAE, Malabu U. Rare case of meningococcal sepsis-induced testicular failure, primary hypothyroidism and hypoadrenalism: Is there a link? BMJ case reports. 2018 Sep 15:2018():. pii: bcr-2018-224437. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-224437. Epub 2018 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 30219775]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMayo J, Collazos J, Martínez E, Ibarra S. Adrenal function in the human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient. Archives of internal medicine. 2002 May 27:162(10):1095-8 [PubMed PMID: 12020177]

Harris P, Bennett A. Waterhouse-Friderichsen syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 2001 Sep 13:345(11):841 [PubMed PMID: 11556316]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKirkgoz T, Guran T. Primary adrenal insufficiency in children: Diagnosis and management. Best practice & research. Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 2018 Aug:32(4):397-424. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2018.05.010. Epub 2018 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 30086866]

Santosh Rai PV, Suresh BV, Bhat IG, Sekhar M, Chakraborti S. Childhood adrenoleukodystrophy - Classic and variant - Review of clinical manifestations and magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of pediatric neurosciences. 2013 Sep:8(3):192-7. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.123661. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24470810]

Westra SJ, Zaninovic AC, Hall TR, Kangarloo H, Boechat MI. Imaging of the adrenal gland in children. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1994 Nov:14(6):1323-40 [PubMed PMID: 7855344]

Espinosa G, Santos E, Cervera R, Piette JC, de la Red G, Gil V, Font J, Couch R, Ingelmo M, Asherson RA. Adrenal involvement in the antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic characteristics of 86 patients. Medicine. 2003 Mar:82(2):106-18 [PubMed PMID: 12640187]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHartle AJ, Peel PH. Etomidate puts patients at risk of adrenal crisis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2012 Nov 6:345():e7444. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7444. Epub 2012 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 23131303]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThompson Bastin ML, Baker SN, Weant KA. Effects of etomidate on adrenal suppression: a review of intubated septic patients. Hospital pharmacy. 2014 Feb:49(2):177-83. doi: 10.1310/hpj4902-177. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24623871]

Tucker WS Jr, Snell BB, Island DP, Gregg CR. Reversible adrenal insufficiency induced by ketoconazole. JAMA. 1985 Apr 26:253(16):2413-4 [PubMed PMID: 3981770]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBurton C, Cottrell E, Edwards J. Addison's disease: identification and management in primary care. The British journal of general practice : the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2015 Sep:65(638):488-90. doi: 10.3399/bjgp15X686713. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26324491]

Bouachour G, Tirot P, Varache N, Gouello JP, Harry P, Alquier P. Hemodynamic changes in acute adrenal insufficiency. Intensive care medicine. 1994:20(2):138-41 [PubMed PMID: 8201094]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHo W, Druce M. Quality of life in patients with adrenal disease: A systematic review. Clinical endocrinology. 2018 Aug:89(2):119-128. doi: 10.1111/cen.13719. Epub 2018 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 29672878]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHirota Y, Matsushita T. Hyperpigmentation as a clue to Addison disease. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2022 Sep 1:89(9):498-499. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.89a.21082. Epub 2022 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 37907439]

Thawabteh AM, Jibreen A, Karaman D, Thawabteh A, Karaman R. Skin Pigmentation Types, Causes and Treatment-A Review. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland). 2023 Jun 18:28(12):. doi: 10.3390/molecules28124839. Epub 2023 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 37375394]

Giannakopoulos A, Sertedaki A, Efthymiadou A, Chrysis D. Addison's disease without hyperpigmentation in pediatrics: pointing towards specific causes. Hormones (Athens, Greece). 2023 Mar:22(1):143-148. doi: 10.1007/s42000-022-00415-5. Epub 2022 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 36348260]

Dickstein G, Shechner C, Nicholson WE, Rosner I, Shen-Orr Z, Adawi F, Lahav M. Adrenocorticotropin stimulation test: effects of basal cortisol level, time of day, and suggested new sensitive low dose test. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1991 Apr:72(4):773-8 [PubMed PMID: 2005201]

Samuels MH. Effects of variations in physiological cortisol levels on thyrotropin secretion in subjects with adrenal insufficiency: a clinical research center study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2000 Apr:85(4):1388-93 [PubMed PMID: 10770171]

Herndon J, Nadeau AM, Davidge-Pitts CJ, Young WF, Bancos I. Primary adrenal insufficiency due to bilateral infiltrative disease. Endocrine. 2018 Dec:62(3):721-728. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1737-7. Epub 2018 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 30178435]

Takahashi K, Kagami S, Kawashima H, Kashiwakuma D, Suzuki Y, Iwamoto I. Sarcoidosis Presenting Addison's Disease. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2016:55(9):1223-8. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.55.5392. Epub 2016 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 27150885]

Guignat L. Therapeutic patient education in adrenal insufficiency. Annales d'endocrinologie. 2018 Jun:79(3):167-173. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2018.03.002. Epub 2018 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 29606279]

Chanson P, Guignat L, Goichot B, Chabre O, Boustani DS, Reynaud R, Simon D, Tabarin A, Gruson D, Reznik Y, Raffin Sanson ML. Group 2: Adrenal insufficiency: screening methods and confirmation of diagnosis. Annales d'endocrinologie. 2017 Dec:78(6):495-511. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2017.10.005. Epub 2017 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 29174200]

Wass JA, Arlt W. How to avoid precipitating an acute adrenal crisis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2012 Oct 9:345():e6333. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6333. Epub 2012 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 23048013]

Amrein K, Martucci G, Hahner S. Understanding adrenal crisis. Intensive care medicine. 2018 May:44(5):652-655. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4954-2. Epub 2017 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 29075801]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArlt W, Society for Endocrinology Clinical Committee. SOCIETY FOR ENDOCRINOLOGY ENDOCRINE EMERGENCY GUIDANCE: Emergency management of acute adrenal insufficiency (adrenal crisis) in adult patients. Endocrine connections. 2016 Sep:5(5):G1-G3 [PubMed PMID: 27935813]

Oelkers W, Diederich S, Bähr V. Diagnosis and therapy surveillance in Addison's disease: rapid adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) test and measurement of plasma ACTH, renin activity, and aldosterone. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1992 Jul:75(1):259-64 [PubMed PMID: 1320051]

Michels A, Michels N. Addison disease: early detection and treatment principles. American family physician. 2014 Apr 1:89(7):563-8 [PubMed PMID: 24695602]

Bornstein SR, Allolio B, Arlt W, Barthel A, Don-Wauchope A, Hammer GD, Husebye ES, Merke DP, Murad MH, Stratakis CA, Torpy DJ. Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2016 Feb:101(2):364-89. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1710. Epub 2016 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 26760044]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChantzichristos D, Eliasson B, Johannsson G. MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE Disease burden and treatment challenges in patients with both Addison's disease and type 1 diabetes mellitus. European journal of endocrinology. 2020 Jul:183(1):R1-R11. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-0052. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32299062]

Zelissen PM, Bast EJ, Croughs RJ. Associated autoimmunity in Addison's disease. Journal of autoimmunity. 1995 Feb:8(1):121-30 [PubMed PMID: 7734032]

Lee SC, Baranowski ES, Sakremath R, Saraff V, Mohamed Z. Hypoglycaemia in adrenal insufficiency. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2023:14():1198519. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1198519. Epub 2023 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 38053731]

Hoek A, Schoemaker J, Drexhage HA. Premature ovarian failure and ovarian autoimmunity. Endocrine reviews. 1997 Feb:18(1):107-34 [PubMed PMID: 9034788]

Milenkovic A, Markovic D, Zdravkovic D, Peric T, Milenkovic T, Vukovic R. Adrenal crisis provoked by dental infection: case report and review of the literature. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2010 Sep:110(3):325-9. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.04.025. Epub 2010 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 20674414]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence