Introduction

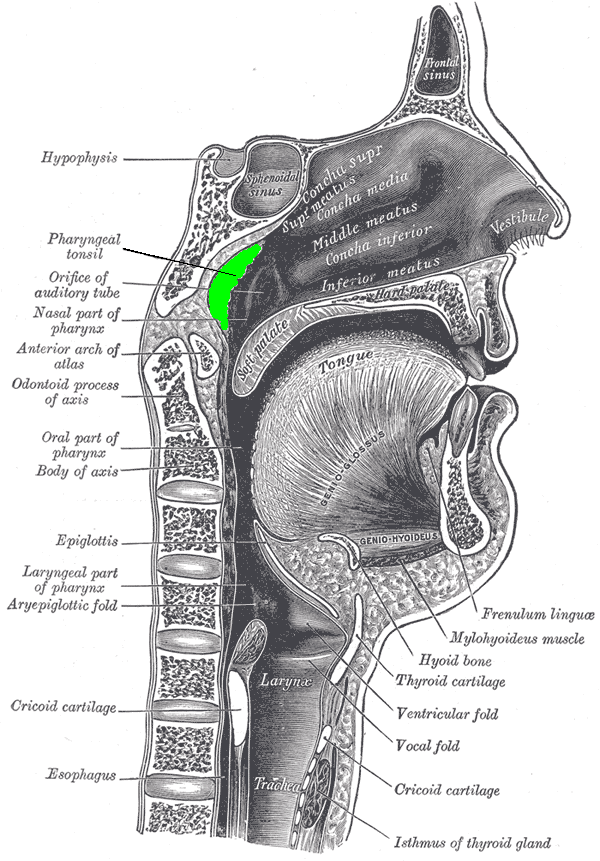

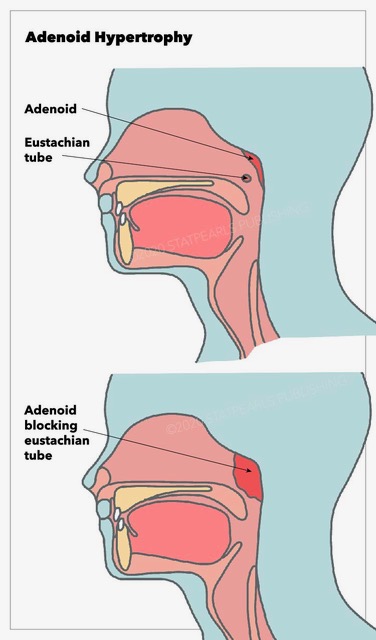

Adenoid hypertrophy is an obstructive condition related to an increased size of the adenoids. The condition can occur with or without an acute or chronic infection of the adenoids. The adenoids are a collection of lymphoepithelial tissue in the superior aspect of the nasopharynx medial to the Eustachian tube orifices. In conjunction with the faucial and lingual tonsils, the adenoids make up the structure known as Waldeyer's ring, a collection of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue situated at the entrance of the upper aerodigestive tract. Blood supply to the adenoids includes the ascending pharyngeal artery, with some contributions from the internal maxillary and facial arteries. The glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves provide sensory innervation to the adenoids. Adenoid size tends to increase during childhood, usually reaching maximal size by age 6 or 7 before regressing by adolescence.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Adenoid hypertrophy can occur because of infectious and non-infectious etiologies. Infectious causes of adenoid hypertrophy include both viral and bacterial pathogens. Viral pathogens associated with adenoid hypertrophy include adenovirus, coronavirus, coxsackievirus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes simplex virus, parainfluenza virus, and rhinovirus.[2][3] Many aerobic bacterial species have been implicated in contributing to infectious adenoid hypertrophy including alpha-, beta-, and gamma-hemolytic Streptococcus species, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.[4][5][2] Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, and Prevotella species have also been identified as anaerobic organisms involved in infectious adenoid hypertrophy.[6][7] Multiple non-infectious causes of adenoid hypertrophy have also been suggested including gastroesophageal reflux[8], allergies, and exposure to cigarette smoke.[9] In adults, adenoid hypertrophy can also be a sign of a more serious condition such as HIV infection[10], lymphoma, or sino-nasal malignancy.[11]

Epidemiology

Adenoid hypertrophy is more common in children than in adults, as the adenoids naturally atrophy and regress during adolescence.[1] A recent meta-analysis showed the prevalence of adenoid hypertrophy among a randomized representative sample of children and adolescents was 34.46%.[12]

Histopathology

Similar to the tonsils, the adenoids are comprised of mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue that can contain germinal centers. The crypt structure is not as pronounced in adenoids as it is in the faucial tonsils.

History and Physical

Adenoid hypertrophy is an obstructive condition, with its symptomatology depending on the obstructed structure. Nasal obstruction by hypertrophic adenoid tissue can cause the patient to complain of rhinorrhea, difficulty breathing through the nose, chronic cough, post-nasal drip, snoring, and/or sleep-disordered breathing in children. If the nasal obstruction is significant, the patient can suffer from sinusitis as a result and may complain of facial pain or pressure. Obstruction of the Eustachian tube can lead to symptoms consistent with Eustachian tube dysfunction such as muffled hearing, otalgia, crackling or popping sounds in the ear, and/or recurrent middle ear infections.[13]

On physical exam, the patient with adenoid hypertrophy will often breathe through the mouth, have a hyponasal character to the voice, and may have the facial characteristics known as adenoid facies which include a high arched hard palate, increased facial height, and midface retrusion.[14][15] A complete physical exam should aim to rule out other potential causes of nasal obstruction such as nasal foreign bodies, rhinosinusitis, nasal polyposis, and congenital abnormalities such as choanal atresia or pyriform aperture stenosis.

Evaluation

A thorough history and physical exam are often sufficient to diagnosed adenoid hypertrophy. Lateral head and neck radiography have been used for assessment of the adenoids, especially in fussy or non-cooperative young children.[16] Videofluoroscopy has also been described as a method for determining the degree of adenoid hypertrophy. Both of these radiographic methods have shown some reliability in diagnosing adenoid hypertrophy. However, both also come with the risk of potentially unnecessary exposure to radiation.[17] Visualization of the adenoids by fiberoptic nasopharyngoscopy is another option for assessing the adenoids in the clinical setting with good reliability and without unnecessary exposure to radiation.[18][19]

Treatment / Management

In acute and chronic infectious adenoid hypertrophy, medical management with antibiotics is the appropriate first step. Amoxicillin can be used for uncomplicated acute adenoiditis, however, a beta-lactamase inhibitor such as clavulanic acid should be included for chronic or recurrent infections. Clindamycin or azithromycin are considered as alternatives in patients with penicillin allergies. Nasal steroids have been suggested as an additional option for medical treatment with some short-term success noted, overall the evidence is mixed as to the efficacy of these medications, and the benefit of reducing the size of the adenoid is predicated on daily, long-term use of the topical medications.[20][21][22](A1)

Adenoidectomy is the surgical treatment option of choice for adenoid hypertrophy. Adenoidectomy is considered for patients with recurrent or persistent obstructive or infectious symptoms related to adenoid hypertrophy.[23][24] Adenoidectomy is performed under general anesthesia with the patient in the supine position with the neck extended slightly and the surgeon seated at the head of the operating table. Adequate exposure of the posterior pharynx is achieved by use of a self-retaining oral retractor, such as a Crowe-Davis mouth gag, and the adenoids are visualized using an angled mirror or a nasal endoscope. Many techniques have been described for performing an adenoidectomy. Sharp instruments such as the adenoid curette or adenotome can be used to sharply dissect the adenoid tissue from the posterior pharyngeal wall, followed by packing of the pharynx or use of suction electrocautery for hemostasis. Suction electrocautery, co-ablation, plasma, laser, and microdebrider instruments have all been described in the literature as tools used for the removal of excessive adenoid tissue during adenoidectomy.[25][26][27] Regardless of the tools employed, the goal of adenoidectomy is the surgical reduction of adenoid tissue mass and/or to eliminate bacterial biofilm from the surface of the adenoid tissue.[28](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Symptoms of adenoid hypertrophy are primarily related to nasal obstruction and Eustachian tube dysfunction. Thus the differential diagnosis should include other causes for these non-specific symptoms, such as:

- Choanal atresia

- Pyriform aperture stenosis

- Allergic rhinitis

- Acute or chronic sinusitis

- Nasal polyposis

- Intranasal encephalocele

- Nasal dermoid

- Nasopharyngeal neoplasm

- Acute otitis media

- Chronic serous otitis media

- Cholesteatoma

- Nasopharyngeal malignancy

- Inverting papilloma

- HIV

The presence of significant and symptomatic adenoid tissue in a young adult or adult should prompt the clinician to more strongly consider neoplastic etiology, as well as other systemic etiologies duch as mononucleosis or HIV.

Prognosis

Adenoid hypertrophy is generally a self-limiting condition which resolves as the adenoids atrophy and regress by adolescence.[1] However, given the potentially serious complications and impact on patient quality of life, surgical management of adenoid hypertrophy is employed for many patients annually. Illustrating this fact, in 2006 there were approximately 506,778 adenotonsillectomies and 129,540 adenoidectomies performed in the United States.[29]

Complications

Complications of adenoid hypertrophy are often seen as complications of persistent middle ear effusion and/or sleep-disordered breathing which can occur as a result of untreated adenoid hypertrophy. Children with adenoid hypertrophy are at risk for developing speech, language, and/or learning difficulties as a result of conductive hearing loss which can occur with persistent secondary middle ear effusion.[30][31] Adenoid hypertrophy also places patients at risk for sleep-disordered breathing and sleep apnea which in children can lead to behavioral problems, bedwetting, pulmonary hypertension, and has been associated with psychiatric disorders such as depression and ADHD.[32]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The risk of bleeding after adenoidectomy is approximately 1 in 1000, with the vast majority of bleeds being self-limited and not requiring intervention. There is a risk of adenoid re-growth, and this is slightly more common in patients who undergo adenoidectomy at a young age.

Consultations

Referral for evaluation by an otolaryngologist should be considered in any child with symptoms suggestive of sleep-disordered breathing, persistent middle ear effusion, and/or recurrent nasal or pharyngeal infections despite adequate treatment with antibiotics.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Educating patients, physicians, and allied health professionals is a key component of providing the best evidence-based care possible to achieve improved patient outcomes.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Adenoid hypertrophy is common in children and is often infectious in origin

- A thorough history and physical exam are often sufficient to make the diagnosis of adenoid hypertrophy

- Flexible nasopharyngoscopy is a safe and reliable alternative to imaging for assessment of adenoid hypertrophy

- Persistent or new-onset adenoid hypertrophy is unusual in adults and may represent a more serious underlying condition such as HIV infection or malignancy, and warrants further investigation

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interprofessional team-based clinics have shown promise in improving health outcomes. Pediatric interprofessional aerodigestive clinics are a common example of this model of patient care. In this setting, nurse educators assist in educating the patient and family. Multiple medical specialists work with the nursing staff in coordinating care. The pharmacist provides guidance in antibiotic selection and monitoring for side effects. In a recent longitudinal case series of patients with persistent symptoms after evaluation and treatment by a single specialist, 73% of patients showed significant improvement in their presenting symptoms after treatment at an interprofessional aerodigestive clinic.[33] (Level V)

While each medical professional certainly has his or her role to play in providing excellent patient care, it is important to consider the collective benefit of a more collaborative team-based approach to providing comprehensive medical care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Goeringer GC, Vidić B. The embryogenesis and anatomy of Waldeyer's ring. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 1987 May:20(2):207-17 [PubMed PMID: 3601384]

Tarasiuk A, Simon T, Tal A, Reuveni H. Adenotonsillectomy in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome reduces health care utilization. Pediatrics. 2004 Feb:113(2):351-6 [PubMed PMID: 14754948]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceProenca-Modena JL, Paula FE, Buzatto GP, Carenzi LR, Saturno TH, Prates MC, Silva ML, Delcaro LS, Valera FC, Tamashiro E, Anselmo-Lima WT, Arruda E. Hypertrophic adenoid is a major infection site of human bocavirus 1. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2014 Aug:52(8):3030-7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00870-14. Epub 2014 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 24920770]

Brook I, Shah K. Bacteriology of adenoids and tonsils in children with recurrent adenotonsillitis. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2001 Sep:110(9):844-8 [PubMed PMID: 11558761]

Swidsinski A, Göktas O, Bessler C, Loening-Baucke V, Hale LP, Andree H, Weizenegger M, Hölzl M, Scherer H, Lochs H. Spatial organisation of microbiota in quiescent adenoiditis and tonsillitis. Journal of clinical pathology. 2007 Mar:60(3):253-60 [PubMed PMID: 16698947]

Holm K, Bank S, Nielsen H, Kristensen LH, Prag J, Jensen A. The role of Fusobacterium necrophorum in pharyngotonsillitis - A review. Anaerobe. 2016 Dec:42():89-97. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2016.09.006. Epub 2016 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 27693542]

Brook I. The role of anaerobic bacteria in tonsillitis. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2005 Jan:69(1):9-19 [PubMed PMID: 15627441]

Ren J, Zhao Y, Ren X. [An association between adenoid hypertrophy and exstra-gastroesophageal reflux disease]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology, head, and neck surgery. 2015 Aug:29(15):1406-8 [PubMed PMID: 26685418]

Evcimik MF, Dogru M, Cirik AA, Nepesov MI. Adenoid hypertrophy in children with allergic disease and influential factors. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2015 May:79(5):694-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.02.017. Epub 2015 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 25758194]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFrance AJ, Kean DM, Douglas RH, Chiswick OM, St Clair D, Best JJ, Goodwin GM, Brettle RP. Adenoidal hypertrophy in HIV-infected patients. Lancet (London, England). 1988 Nov 5:2(8619):1076 [PubMed PMID: 2903300]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRout MR, Mohanty D, Vijaylaxmi Y, Bobba K, Metta C. Adenoid Hypertrophy in Adults: A case Series. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2013 Jul:65(3):269-74. doi: 10.1007/s12070-012-0549-y. Epub 2012 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 24427580]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePereira L, Monyror J, Almeida FT, Almeida FR, Guerra E, Flores-Mir C, Pachêco-Pereira C. Prevalence of adenoid hypertrophy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews. 2018 Apr:38():101-112. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.001. Epub 2017 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 29153763]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBuzatto GP, Tamashiro E, Proenca-Modena JL, Saturno TH, Prates MC, Gagliardi TB, Carenzi LR, Massuda ET, Hyppolito MA, Valera FC, Arruda E, Anselmo-Lima WT. The pathogens profile in children with otitis media with effusion and adenoid hypertrophy. PloS one. 2017:12(2):e0171049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171049. Epub 2017 Feb 23 [PubMed PMID: 28231295]

Peltomäki T. The effect of mode of breathing on craniofacial growth--revisited. European journal of orthodontics. 2007 Oct:29(5):426-9 [PubMed PMID: 17804427]

Harari D, Redlich M, Miri S, Hamud T, Gross M. The effect of mouth breathing versus nasal breathing on dentofacial and craniofacial development in orthodontic patients. The Laryngoscope. 2010 Oct:120(10):2089-93. doi: 10.1002/lary.20991. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20824738]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFeres MF, Hermann JS, Cappellette M Jr, Pignatari SS. Lateral X-ray view of the skull for the diagnosis of adenoid hypertrophy: a systematic review. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2011 Jan:75(1):1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.11.002. Epub 2010 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 21126775]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYsunza A, Pamplona MC, Ortega JM, Prado H. Video fluoroscopy for evaluating adenoid hypertrophy in children. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2008 Aug:72(8):1159-65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.03.022. Epub 2008 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 18479759]

Lertsburapa K, Schroeder JW Jr, Sullivan C. Assessment of adenoid size: A comparison of lateral radiographic measurements, radiologist assessment, and nasal endoscopy. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2010 Nov:74(11):1281-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.08.005. Epub 2010 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 20828838]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceParikh SR, Coronel M, Lee JJ, Brown SM. Validation of a new grading system for endoscopic examination of adenoid hypertrophy. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2006 Nov:135(5):684-7 [PubMed PMID: 17071294]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChohan A, Lal A, Chohan K, Chakravarti A, Gomber S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the role of mometasone in adenoid hypertrophy in children. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2015 Oct:79(10):1599-608. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.07.009. Epub 2015 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 26235732]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDemirhan H, Aksoy F, Ozturan O, Yildirim YS, Veyseller B. Medical treatment of adenoid hypertrophy with "fluticasone propionate nasal drops". International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2010 Jul:74(7):773-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.03.051. Epub 2010 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 20430451]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKuhle S, Urschitz MS. Anti-inflammatory medications for obstructive sleep apnea in children. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2011 Jan 19:(1):CD007074. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007074.pub2. Epub 2011 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 21249687]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRosenfeld RM, Shin JJ, Schwartz SR, Coggins R, Gagnon L, Hackell JM, Hoelting D, Hunter LL, Kummer AW, Payne SC, Poe DS, Veling M, Vila PM, Walsh SA, Corrigan MD. Clinical Practice Guideline: Otitis Media with Effusion (Update). Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2016 Feb:154(1 Suppl):S1-S41. doi: 10.1177/0194599815623467. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26832942]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBaugh RF, Archer SM, Mitchell RB, Rosenfeld RM, Amin R, Burns JJ, Darrow DH, Giordano T, Litman RS, Li KK, Mannix ME, Schwartz RH, Setzen G, Wald ER, Wall E, Sandberg G, Patel MM, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillectomy in children. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2011 Jan:144(1 Suppl):S1-30. doi: 10.1177/0194599810389949. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21493257]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSjogren PP, Thomas AJ, Hunter BN, Butterfield J, Gale C, Meier JD. Comparison of pediatric adenoidectomy techniques. The Laryngoscope. 2018 Mar:128(3):745-749. doi: 10.1002/lary.26904. Epub 2017 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 29152748]

Ida JB, Worley NK, Amedee RG. Gold laser adenoidectomy: long-term safety and efficacy results. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2009 Jun:73(6):829-31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.02.020. Epub 2009 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 19324425]

Kuo CY, Lin YY, Chen HC, Shih CP, Wang CH. Video Nasoendoscopic-Assisted Transoral Adenoidectomy with the PEAK PlasmaBlade: A Preliminary Report of a Case Series. BioMed research international. 2017:2017():1536357. doi: 10.1155/2017/1536357. Epub 2017 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 28459055]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDrago L, De Vecchi E, Torretta S, Mattina R, Marchisio P, Pignataro L. Biofilm formation by bacteria isolated from upper respiratory tract before and after adenotonsillectomy. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 2012 May:120(5):410-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02846.x. Epub 2011 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 22515296]

Bhattacharyya N, Lin HW. Changes and consistencies in the epidemiology of pediatric adenotonsillar surgery, 1996-2006. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2010 Nov:143(5):680-4. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.06.918. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20974339]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLehmann MD, Charron K, Kummer A, Keith RW. The effects of chronic middle ear effusion on speech and language development -- a descriptive study. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 1979 Sep:1(2):137-44 [PubMed PMID: 553891]

Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, Tunkel DE, Hussey HM, Fichera JS, Grimes AM, Hackell JM, Harrison MF, Haskell H, Haynes DS, Kim TW, Lafreniere DC, LeBlanc K, Mackey WL, Netterville JL, Pipan ME, Raol NP, Schellhase KG. Clinical practice guideline: Tympanostomy tubes in children. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2013 Jul:149(1 Suppl):S1-35. doi: 10.1177/0194599813487302. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23818543]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHuang YS, Guilleminault C. Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Where Do We Stand? Advances in oto-rhino-laryngology. 2017:80():136-144. doi: 10.1159/000470885. Epub 2017 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 28738322]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRotsides JM, Krakovsky GM, Pillai DK, Sehgal S, Collins ME, Noelke CE, Bauman NM. Is a Multidisciplinary Aerodigestive Clinic More Effective at Treating Recalcitrant Aerodigestive Complaints Than a Single Specialist? The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2017 Jul:126(7):537-543. doi: 10.1177/0003489417708579. Epub 2017 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 28474959]