Introduction

Elbow arthrocentesis is a procedure performed to aspirate the contents of a joint cavity to evaluate and treat elbow effusion. Arthrocentesis is considered a minor surgical procedure. However, there is always the chance, as with introducing any needle through the skin, for infection, injury to nerves, vessels, tendons, or other connective tissue. Therefore, this procedure should only be performed by health care providers trained in arthrocentesis with a strong understanding of elbow anatomy. Arthrocentesis is commonly used to evaluate the underlying etiology of joint effusion, including infectious, inflammatory, and hemorrhagic causes. Aspiration of the joint space and removal of the contents reduces the fluid pressure in the joint capsule and reduces pain. Additionally, access to the joint space provides the opportunity to inject therapeutic agents in the setting of pain or degenerative joint disease. Of the etiologies above, the most important to diagnose properly is septic arthritis, as cultures are crucial to prompt and adequate treatment.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Osseous

The distal humerus, radial head, and olecranon comprise the elbow joint. The olecranon process articulates with the trochlea of the humeral condyle forming a hinge joint for flexion and extension. The radial head is held in place with the annular ligament arising from the proximal ulna and articulates with the ulna and the distal humerus. The joint is encapsulated and contains the articular surfaces of the structures mentioned above. This space contains synovial fluid and is the target of elbow aspiration.

Muscular Compartments

The biceps crosses the elbow anteriorly, and the triceps crosses the elbow posteriorly, facilitating flexion and extension, respectively. The flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, humeroulnar head of flexor digitorum superficials, and the humeral head of the flexor carpi ulnaris contribute to the flexor compartment and supination of the wrist originating at the medial epicondyle. They primarily receive innervation via the median nerve. The wrist extensors and supinators, including extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digitorum, and extensor digiti minimi, all originate on the lateral epicondyle and are innervated by the radial nerve.

Vasculature

Blood supply to the elbow is via extensive anastomoses originating from the brachial and radial arteries

Positioning

The patient should have their elbow bent to 90 degrees with their hand pronated (palm down); this exposes the approach trajectory by rolling the head of the radius out of the way.

The aiming point for needle insertion is the juncture of the lateral humeral condyle, radial head, and olecranon process. These three landmarks form the anconeus triangle, and the insertion point is located centrally. The needle is then inserted into the sulcus directed medial and perpendicular to the radius toward the distal end of the antecubital fossa.

Ultrasound guidance for evaluation of fluid collection and needle guidance is recommended.

Indications

Elbow arthrocentesis is performed to aspirate effusions for two reasons, both diagnosis and therapeutic relief of pain caused by fluid pressure. Diagnostically the primary etiologies of concern are septic arthritis, hemarthrosis, and inflammation. Of these, a suspected septic joint and crystalline arthropathy are the two most common indications. Additionally, arthrocentesis may help to evaluate the therapeutic response for septic arthritis or unexplained arthritis with synovial effusion. Although not the topic of this discussion, access to the joint space may also be used to inject therapeutic agents and to challenge the joint with fluid for evaluation of joint capsule integrity if any overlying laceration is present.[1]

Contraindications

The only absolute contraindication to arthrocentesis is overlying cellulitis, which may lead to seeding of the joint with bacteria.[2] Relative contraindications include coagulopathy, joint prosthesis, acute fracture, and adjacent osteomyelitis. Prosthetic joints warrant discussion with orthopedic surgery before tapping, as many surgeons believe a prosthetic joint should only undergo tapping in the operative theater.

Equipment

- Iodine solution or chlorhexidine

- Sterile gloves and drape

- Sterile gauze

- Sterile fenestrated drapes

- Lure-Lok syringes including one 5cc and another 5 to 20cc syringe

- 20G and 27G needle

- 1% Lidocaine or 0.5% bupivacaine

- Collection tubes including a hematology tube, sterile tube, heparinized tube

- Ultrasound with a sterile cover, if available

Personnel

This procedure can take place without an assistant; however, an assistant may make certain situations, including an anxious patient or unforeseen technical difficulties, easier.

Preparation

There are no stat indications for elbow arthrocentesis; thus, additional time can help improve a first-attempt success rate and reduce associated risks. Ensure all necessary equipment is available and works appropriately, correctly identify landmarks, and adhere to a sterile technique.

Technique or Treatment

Position your patient with the elbow bent 90 degrees and pronated palm down. This position rolls the radial head to open the joint space. Use an ultrasound if available to localize fluid collection and direct the needle. Mark the approach by identifying the insertion site inferior to the lateral humeral epicondyle, anterior to the olecranon, and superior/posterior to the radial head (anconeus triangle). Use a skin pen to mark or pressure to indent the surface of the skin. Now clean the area with a wide margin using chlorhexidine or iodine solution. Gown, glove, and then drape in a sterile fashion. Raise a bleb of 1% lidocaine using a sterile technique at the site of insertion. Once anesthetized, an 18 to 22 gauge needle 1.5 inches long is attached to a 5 to 10mL syringe and advanced into the joint space while retracting to watch for blood return. Once the joint space is accessed, synovial fluid, blood, or infectious material may be aspirated. With the needle held in place, multiple syringes may be used to aspirate all the contents of the joint. If inflammatory etiology is suspected, a glucocorticoid may be injected before leaving the joint space to prevent relapse of effusion.[3] The needle is then withdrawn, a bandage is applied, and the collected fluid is sent to the lab. Studies should include fluid gram stain and culture, cell count with differential, protein, glucose, and polarized light microscopy for crystalline arthropathies.[4][1][5]

Other Considerations

Joint aspiration is safe within the therapeutic range of anticoagulation with warfarin or properly dosed DOAC. Considerations for the anticoagulated patient includes using a smaller needle size.[6][7][8]

Ultrasonography may be used in a sterile fashion to guide the needle if dry tap occurs, and septic arthritis is suspected.[9]

Shaving is of no benefit.

Complications

Even though complications with arthrocentesis are rare, the clinician should take the time to inform the patient of potential complications arising from arthrocentesis. There are two major categories to take into consideration; infectious complications and noninfectious complications. Of the complications, the most feared is septic arthritis.[10] The frequency of this complication lies somewhere between 1 in 2000 and 1 in 15000. It is best avoided by maintaining a sterile field, minimizing attempts, using single-dose vials, changing to a new needle after drawing up medication before injecting, and preventing the introduction of a needle through cellulitis. The other concerning infection is septic bursitis, which arises when the needle approach travels through a bursa, the olecranon bursa in the case of the elbow, on the way to the joint and is due to direct inoculation from skin flora. Noninfectious complications that arise include tendon rupture, vascular damage, and neurologic damage. All three complications directly result from trauma secondary to the penetrating needle and are more common when injecting glucocorticoids than aspirating. These complications are mediated by carefully planning the approach and identifying the proper anatomical location for insertion and needle travel. Bleeding management is with tamponade. The patient should also be informed there may be a recurrence of joint effusion until the resolution of the underlying etiology.[1]

Clinical Significance

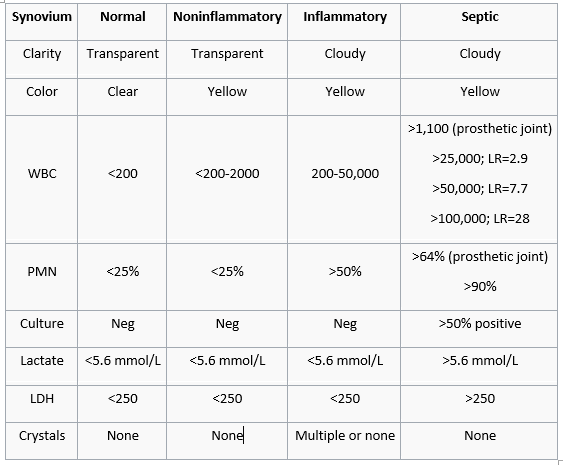

Arthrocentesis is a valuable procedure for determining the etiology of joint effusion. Evaluation of the aspirated fluid can serve to classify the effusion into non-inflammatory, inflammatory, septic, and hemorrhagic. Septic arthritis is typically mono-microbial and broken down into two categories, gonococcal and non-gonococcal, based on age and history. Adults < 35 years old have infections from N. gonorrhea. Adults > 35 years old are most likely to present with S. aureus infections. History, such as recent travel and immunocompromised states, can clue the provider into other causative organisms, including Strep. spp, aerobic gram-negative, anaerobic gram-negative, brucellosis, Mycobacteria spp, fungal, and Mycoplasma hominis. Crystalline arthritis and autoimmune disease can cause an inflammatory joint effusion. Trauma is the most common cause of hemorrhagic joint effusion, but there are case reports of supratherapeutic INRs associated with spontaneous hemarthrosis.

See the attached graph below.

- Negatively birefringent crystals = gout

- Positive bi-refringent crystals = pseudogout

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ensuring proper fluid analysis with gram stain and culture is vital to the purpose of arthrocentesis. It is essential to communicate fluid analysis orders with the lab technician and if able to walk the fluid specimens directly to the lab to ensure timely fluid analysis. Clear communication will prevent unnecessary use of long-term empiric antibiotics and improve patient therapy by tailoring the treatment to the proper diagnosis.

Media

References

Bettencourt RB, Linder MM. Arthrocentesis and therapeutic joint injection: an overview for the primary care physician. Primary care. 2010 Dec:37(4):691-702, v. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2010.07.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21050951]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmyth TT, Chirino-Trejo M, Carmalt JL. In vitro assessment of bacterial translocation during needle insertion through inoculated culture media as a model of arthrocentesis through cellulitic tissue. American journal of veterinary research. 2015 Oct:76(10):877-81. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.76.10.877. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26413825]

Weitoft T, Uddenfeldt P. Importance of synovial fluid aspiration when injecting intra-articular corticosteroids. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2000 Mar:59(3):233-5 [PubMed PMID: 10700435]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSternbach GL, Baker FJ 2nd. The emergency joint: arthrocentesis and synovial fluid analysis. JACEP. 1976 Oct:5(10):787-92 [PubMed PMID: 1018355]

Self WH, Wang EE, Vozenilek JA, del Castillo J, Pettineo C, Benedict L. Dynamic emergency medicine. Arthrocentesis. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008 Mar:15(3):298. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00054.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18304064]

Thumboo J, O'Duffy JD. A prospective study of the safety of joint and soft tissue aspirations and injections in patients taking warfarin sodium. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1998 Apr:41(4):736-9 [PubMed PMID: 9550485]

Yui JC, Preskill C, Greenlund LS. Arthrocentesis and Joint Injection in Patients Receiving Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2017 Aug:92(8):1223-1226. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28778256]

Conway R, O'Shea FD, Cunnane G, Doran MF. Safety of joint and soft tissue injections in patients on warfarin anticoagulation. Clinical rheumatology. 2013 Dec:32(12):1811-4. doi: 10.1007/s10067-013-2350-z. Epub 2013 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 23925554]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSibbitt WL Jr, Peisajovich A, Michael AA, Park KS, Sibbitt RR, Band PA, Bankhurst AD. Does sonographic needle guidance affect the clinical outcome of intraarticular injections? The Journal of rheumatology. 2009 Sep:36(9):1892-902. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090013. Epub 2009 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 19648304]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRoss JJ. Septic Arthritis of Native Joints. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2017 Jun:31(2):203-218. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.01.001. Epub 2017 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 28366221]