Introduction

A knee arthrocentesis is a minor surgical procedure to aspirate synovial fluid from the knee joint. The procedure has diagnostic and therapeutic uses as it drains fluid and diagnoses the etiology of the underlying knee pathology. During arthrocentesis, blood vessels, nerves, and tendons can always be injured. Clinicians with extensive knowledge of the knee's anatomy, training, and credentialing should perform the procedure.

The knee is the largest synovial cavity in the body and is easily accessible from either the medial or lateral aspect and superior or inferior to the midpoint of the patella. The patient can be supine or sitting, but fluid is more easily aspirated in the supine position. To minimize the risk of injury, the joint's surface should be in extension with minimal (20°) flexion under ultrasound guidance, as this approach improves aspiration volume, accuracy rates, and pain scores.[1][2][3][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomical considerations for knee arthrocentesis are:

- The patient is in either the supine or sitting position.

- The clinician can access the knee medially or laterally to the patella or superiorly or inferiorly to the patella.

- The patient should fully extend the affected knee or relax the quadriceps muscle at 20° flexion.

- The clinician should place their thumb on the patella and push it aside as they insert the needle.

- For the suprapatellar approach, the anatomical landmarks should be 1 cm lateral and 1 cm superior to the superior aspect of the patella.

- Upon identifying the midpoint of the patella, the needle can be inserted either 1 cm laterally or medially.

- The clinician should aim the needle posterior to the patella and superiorly toward the joint space, then squeeze both sides to facilitate aspiration.

Indications

The procedure is completed in the office, emergency room, or operating room. The therapeutic or diagnostic indications are listed below:

- Therapeutic

- Diagnostic

- Etiology of acute arthritis

- Differentiation between septic arthritis and an inflammatory cause of bloody mono-arthritis

Contraindications

No absolute contraindications are recognized for this procedure but several relative contraindications include:

- Overlying cellulitis (potential intra-articular seeding of bacteria)

- Coagulopathy or bleeding disorders

- A joint prosthesis (preferably by an orthopedic surgeon)

- An acute fracture

- Adjacent osteomyelitis

- Uncooperative or combative patients

Equipment

Before the procedure, obtaining all the supplies and materials at the bedside is important. Standard equipment includes:

- Skin cleansing solution (betadine, chlorhexidine, etc)

- Skin marking pen

- Sterile gloves

- Sterile gauze

- 1% lidocaine with or without epinephrine

- 10 cc syringe for the lidocaine

- 30 to 60 cc syringe

- 18 g needle for aspiration

- Small 27 g needle for anesthetic injection

- Specimen tubes (cell count, gram stain, culture, and sensitivity in addition to crystal analysis for gout and pseudogout)

Further, an ultrasound helps identify proper anatomical landmarks. Study results have shown ultrasound improves accuracy, aspiration volume, and pain scores at 2 weeks post-procedure.[3][4]

Personnel

A skilled clinician can perform the procedure independently. If the patient is anxious or exceptional circumstances apply, assistance on knee position, fluid collection, medication administration, or procedural sedation is recommended.

Preparation

A knee aspiration can be anxiety-provoking for some patients, though it is a non-invasive procedure. Thus, an anxious patient who is in pain or unable to cooperate with the procedure might require assistance and oral or intravenous procedural sedation. Local anesthesia is strongly recommended. For most clinicians, the use of plain 1% lidocaine without epinephrine is commonly used to anesthetize the skin. However, no downside is apparent to using either 2% lidocaine, lidocaine with epinephrine, or bupivacaine when indicated. Avoiding deeper injections with the local anesthetic is preferred (due to the risk of infiltrating into the joint space, which may alter the synovial fluid analysis).

Technique or Treatment

The clinician must obtain informed consent before performing this procedure. A timeout should take place to confirm the patient and the correct joint. The most crucial step is having the patient lie in a comfortable position with the affected knee fully extended or flexed at 15° to 20° with a towel rolled under the knee. This position facilitates a successful procedure by ensuring quadriceps muscle relaxation.

Various studies have evaluated 2 positions of knee arthrocentesis, including the sitting and supine positions. When performed on a patient who is supine with an extended knee, the procedure is more accurate and successful than when performed on a patient who is sitting. Evidence supports the benefit of the procedure on the extended knee rather than the flexed knee when the superolateral aspiration approach is used.

The success rate is similar in the flexed position when mechanical compression is applied to the superior aspect of the knee.

The following steps comprise the procedure:

- The clinician should locate the patella with a marking pen.[4][9]

- The area should be sterilized and draped.

- After selecting the preferred approach, the superficial skin and deeper tissue in the projected trajectory of joint aspiration should be anesthetized.

- For the midpoint approach, insert an 18 g needle with a 30 cc to 60 cc syringe 1 cm lateral or medial to the patella, directing the needle posterior and horizontal toward the intercondylar notch of the femur. The superior approach is performed 1 cm superior and one cm medial or lateral to the patella, directing it towards the femur’s intercondylar notch. The infrapatellar approach requires the patient to sit upright, flexing the knee at 90°. Needle insertion is 5 mm below the patella’s inferior border, posterior to the patellar tendon, a less desirable approach.

- Pull back lightly on the syringe when advancing the needle and stop when aspirating synovial fluid.

- Attempt to aspirate as much fluid as possible. “Milking” or compressing the joint during the procedure helps facilitate fluid aspiration.

- After the fluid is aspirated, all specimen tubes are filled using a sterile technique.

- The needle and syringe can be removed simultaneously if no further injections are required.

If an additional injection is needed, the syringe needle head should be replaced according to sterile protocol. Depending on the local tissue injury, the appropriate dressings could be applied.

Complications

Complications can arise from local trauma, including damage to nearby structures, pain, infection, and reaccumulation of effusion. If the needle placement is poor or the synovium is thickened, it may result in a dry tap and a need to redirect the needle or change the approach. When the needle's angle is changed during the procedure, the needle is withdrawn to the skin surface. Changing the angle in the deeper soft tissue or knee joint can cause the needle bevel to tear through soft tissue and adjacent structures, causing lacerated tissue and bleeding.[10][11]

Hemarthrosis can occur if a large needle damages a blood vessel on multiple attempts. In most cases, hemarthrosis presents a few hours after the procedure; this is often associated with joint pain, stiffness, and swelling. The majority of hemarthrosis is self-limited and resolves within a few weeks. Results from a study evaluating the risk of complications in patients taking Dabigatran showed an incidence of hemarthrosis of less than 1%, and other recommendations suggest that anticoagulation does not need to be discontinued. [12][13][14]

Another uncommon complication is an arterioarticular fistula. If the patient has a coagulopathy, it may need to be corrected before the procedure is performed, and consultation with a hematologist is warranted. However, under certain circumstances, like the evaluation of a potential septic arthritis, the procedure might need to be performed regardless of anticoagulant use status. The hemarthrosis risk is still low under those circumstances.

If an arthrocentesis is performed through an infected skin area to look for a septic joint, prescribing antibiotics is the standard of care. If fear of an infected joint is evidenced, the cost of treatment delay is greater than joint aspiration through overlying cellulitis.[15] In the absence of overlying cellulitis, the risk of inoculation still exists. Although rare, reported rates are around 1 in 2034 to 1 in 3500 procedures.[16]

Clinical Significance

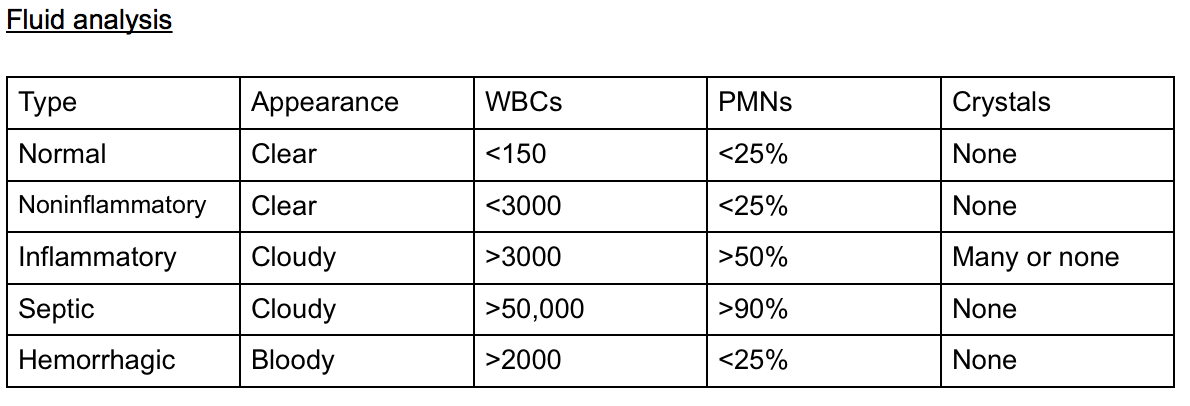

Knee arthrocentesis is performed to identify the etiology, relieve pain, and initiate effusion drainage (see Image. Fluid Analysis of Knee Arthrocentesis). The clinician should be familiar with the anatomy to avoid complications. Using an appropriate technique can minimize the risk of complications.

Crystal analysis is usually the result of a successful knee aspiration. The clinician commonly differentiates gout (negatively birefringent urate crystals), pseudogout (weakly positive birefringent crystals), and an infectious process by the presence of white blood cells (WBCs) and/or a positive gram stain. The presence of crystals does not rule out concomitant septic arthritis.[17]

The synovial fluid analysis associated with a septic or infectious joint effusion can have different findings. A normal synovial fluid should be acellular with little to no white blood cell count (WBC), increasing in likelihood ratio as WBC mm3 rises from 25,000 to 150,000 mm3. Each of these findings has sensitivity and specificity for ruling in or ruling out infection before the cultures return, as a commonly used WBC cutoff to diagnose a septic joint at 50,000 synovial WBC mm3 has been found to lack the sensitivity to rule out infection.[18][19][20] Some studies state that most cases of septic arthritis have synovial WBC counts of <50,000.[21]

- Total WBC higher than 25,000/microliter (approximately 75% sensitive, 75% specific, and a likelihood ratio [LR] of +2.9)[18]

- Total WBC higher than 50,000/microliter (approximately 60% sensitive, approximately 90% specific, and a +LR of 7.7)

- Total WBC higher than 100,000/microliter (approximately 20% sensitive, approximately 99% specific and a +LR of 28)

- PMN cell proportion 0.9 or higher (approximately 75% specific, 80% sensitive)

- Lactic dehydrogenase concentration higher than 250 U/L (approximately 100% sensitive, 50% specific)

- Synovial glucose or serum glucose concentration lower than 0.5 (approximately 50% sensitive, 85% specific)

- Protein concentration higher than 3 g/dL (approximately 50% sensitive, 50% specific)

A gram stain of the fluid is recommended as it informs therapy and treatment. This process has a 29% to 50% sensitivity in diagnosis as it can miss early infections and those from fungal, mycobacteria, and mycoplasma causes. In some instances, the synovial fluid analysis remains inconclusive, and a synovial biopsy is recommended to help rule out autoimmune conditions and detect atypical organisms.[22]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A knee arthrocentesis is often an outpatient procedure in the emergency department or operating room. However, in most cases, a primary care clinician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner should consult the orthopedic surgeon. To avoid complications, only clinicians familiar with the indications, anatomy, and understanding of potential complications should aspirate the knee.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Situ-LaCasse E, Grieger RW, Crabbe S, Waterbrook AL, Friedman L, Adhikari S. Utility of point-of-care musculoskeletal ultrasound in the evaluation of emergency department musculoskeletal pathology. World journal of emergency medicine. 2018:9(4):262-266. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2018.04.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30181793]

Partridge DG, Winnard C, Townsend R, Cooper R, Stockley I. Joint aspiration, including culture of reaspirated saline after a 'dry tap', is sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of hip and knee prosthetic joint infection. The bone & joint journal. 2018 Jun 1:100-B(6):749-754. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.100B6.BJJ-2017-0970.R2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29855250]

Wu T, Dong Y, Song Hx, Fu Y, Li JH. Ultrasound-guided versus landmark in knee arthrocentesis: A systematic review. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2016 Apr:45(5):627-32. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.10.011. Epub 2015 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 26791571]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZhang Q, Zhang T, Lv H, Xie L, Wu W, Wu J, Wu X. Comparison of two positions of knee arthrocentesis: how to obtain complete drainage. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2012 Jul:91(7):611-5. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31825a13f0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22710881]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJennings JM, Dennis DA, Kim RH, Miner TM, Yang CC, McNabb DC. False-positive Cultures After Native Knee Aspiration: True or False. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2017 Jul:475(7):1840-1843. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-5194-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27942968]

Bhavsar TB, Sibbitt WL Jr, Band PA, Cabacungan RJ, Moore TS, Salayandia LC, Fields RA, Kettwich SK, Roldan LP, Suzanne Emil N, Fangtham M, Bankhurst AD. Improvement in diagnostic and therapeutic arthrocentesis via constant compression. Clinical rheumatology. 2018 Aug:37(8):2251-2259. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3836-x. Epub 2017 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 28913649]

Shahid A, Malik A, Bukhari A, Shaikh A, Rutherford J, Barkatali B. Do Platelet-Rich Plasma Injections for Knee Osteoarthritis Work? Cureus. 2023 Feb:15(2):e34533. doi: 10.7759/cureus.34533. Epub 2023 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 36751575]

Eker HE, Cok OY, Aribogan A, Arslan G. The efficacy of intra-articular lidocaine administration in chronic knee pain due to osteoarthritis: A randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Anaesthesia, critical care & pain medicine. 2017 Apr:36(2):109-114. doi: 10.1016/j.accpm.2016.05.003. Epub 2016 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 27485803]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYaqub S, Sibbitt WL Jr, Band PA, Bennett JF, Emil NS, Fangtham M, Fields RA, Hayward WA, Kettwich SK, Roldan LP, Bankhurst AD. Can Diagnostic and Therapeutic Arthrocentesis Be Successfully Performed in the Flexed Knee? Journal of clinical rheumatology : practical reports on rheumatic & musculoskeletal diseases. 2018 Sep:24(6):295-301. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000707. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29424762]

Battistone MJ, Barker AM, Grotzke MP, Beck JP, Berdan JT, Butler JM, Milne CK, Huhtala T, Cannon GW. Effectiveness of an Interprofessional and Multidisciplinary Musculoskeletal Training Program. Journal of graduate medical education. 2016 Jul:8(3):398-404. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00391.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27413444]

Kontovazenitis PI, Starantzis KA, Soucacos PN. Major complication following minor outpatient procedure: osteonecrosis of the knee after intraarticular injection of cortisone for treatment of knee arthritis. Journal of surgical orthopaedic advances. 2009 Spring:18(1):42-4 [PubMed PMID: 19327266]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorag Y, Ford MK, Jacobson JA, Jamadar DA. Sonographic diagnosis of an arterioarticular fistula following knee arthrocentesis. Journal of clinical ultrasound : JCU. 2006 May:34(4):207-9 [PubMed PMID: 16615056]

Tarar MY, Choo XY, Khan S. The Risk of Bleeding Complications in Intra-Articular Injections and Arthrocentesis in Patients on Novel Oral Anticoagulants: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2021 Sep:13(9):e17755. doi: 10.7759/cureus.17755. Epub 2021 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 34659968]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYui JC, Preskill C, Greenlund LS. Arthrocentesis and Joint Injection in Patients Receiving Direct Oral Anticoagulants. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2017 Aug:92(8):1223-1226. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28778256]

Dooley DP. Aspiration of the possibly septic joint through potential cellulitis: just do it! The Journal of emergency medicine. 2002 Aug:23(2):210 [PubMed PMID: 12359298]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGeirsson AJ, Statkevicius S, Víkingsson A. Septic arthritis in Iceland 1990-2002: increasing incidence due to iatrogenic infections. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2008 May:67(5):638-43 [PubMed PMID: 17901088]

Guyver PM, Arthur CH, Hand CJ. The acutely swollen knee. Part 1: Management of atraumatic pathology. Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service. 2014:100(1):24-33 [PubMed PMID: 24881423]

McGillicuddy DC, Shah KH, Friedberg RP, Nathanson LA, Edlow JA. How sensitive is the synovial fluid white blood cell count in diagnosing septic arthritis? The American journal of emergency medicine. 2007 Sep:25(7):749-52 [PubMed PMID: 17870475]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMargaretten ME, Kohlwes J, Moore D, Bent S. Does this adult patient have septic arthritis? JAMA. 2007 Apr 4:297(13):1478-88 [PubMed PMID: 17405973]

Baer PA, Tenenbaum J, Fam AG, Little H. Coexistent septic and crystal arthritis. Report of four cases and literature review. The Journal of rheumatology. 1986 Jun:13(3):604-7 [PubMed PMID: 3735282]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEren TK, Aktekin CN. How reliable are the synovial cell count and blood parameters in the diagnosis of septic arthritis? Joint diseases and related surgery. 2023 Aug 21:34(3):724-730. doi: 10.52312/jdrs.2023.1222. Epub 2023 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 37750279]

Darraj H, Hakami KM, Zogel B, Maghrabi R, Khired Z. Septic Arthritis of the Knee in Children. Cureus. 2023 Sep:15(9):e45659. doi: 10.7759/cureus.45659. Epub 2023 Sep 21 [PubMed PMID: 37868524]