Introduction

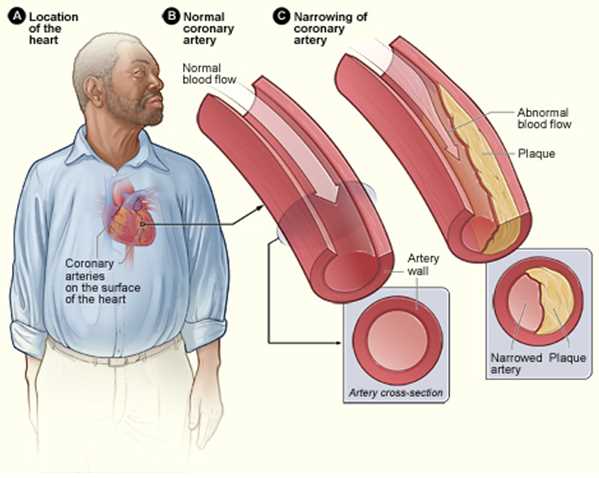

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the arteries and is the underlying cause of about 50% of all deaths in westernized society. It is principally a lipid-driven process initiated by the accumulation of low-density lipoprotein and remnant lipoprotein particles and an active inflammatory process in focal areas of arteries particularly at regions of disturbed non-laminar flow at branch points in the arteries and is considered a primary cause of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) resulting in heart attacks, stroke and peripheral arterial disease. In this review, we outline the vascular biology, sequelae and potential management.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

ASCVD is of multifactorial etiology. The most common risk factors include hypercholesterolemia (LDL-cholesterol), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, age (male older than 45 years and female older than 55 years), male gender, and strong family history (male relative younger than 55 years and female relative younger than 65 years. Also, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, diets high in saturated and trans-fatty acids, and certain genetic mutations contribute to risk. While a low level of high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol is considered a risk factor, pharmacological therapy increasing HDL-cholesterol has yielded negative results raising concerns about the role of HDL in ASCVD.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

Since atherosclerosis is a predominantly asymptomatic condition, it is difficult to determine the incidence accurately. Atherosclerosis is considered the major cause of cardiovascular diseases. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease mainly involves the heart and brain: ischemic heart disease (IHD) and ischemic stroke. IHD and stroke are the world's first and fifth causes of death respectively. [7][8][9][10]

In the United States, about 610,000 people die of heart disease every year. That is 1 of every 4 deaths. Coronary heart disease is the leading cause of death in the Western world killing over 370,000 people annually. On an average, about 735,000 Americans have a heart attack every year. Out of these, 525,000 have an initial attack, and 210,000 have a recurrent attack. It has been reported that 75% of acute myocardial infarctions occur from plaque rupture and the highest incidence of plaque rupture was observed in men over 45 years; whereas, in women, the incidence increases beyond age 50 years. This higher prevalence of atherosclerosis in men compared to women is attributed to the protective function of female sex hormones but is lost after menopause.

Stroke from any cause represents the fifth leading cause of death and the major cause of serious long-term disability in adults in the United States. It is reported that nearly 795,000 people suffer from stroke every year in the US resulting in about 140,323 deaths. The major form of stroke, ischemic stroke is due to ASCVD.

Many epidemiologic studies in North America and Europe have recognized numerous risk factors for the development and progression of atherosclerosis. They may promote atherosclerosis through their effects on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles and inflammation.

Pathophysiology

Atherosclerosis mainly develops through the continuous process of arterial wall lesions due to lipid retention by trapping in the intima by a matrix such as proteoglycans resulting in a modification which, in turn, aggravates chronic inflammation at vulnerable sites in the arteries and plays an important role at all phases of the atherogenic progression. This process begins from the nascent fatty streaks in the arterial intima which evolve into fibrous plaques and emerges into complex atherosclerotic lesions that are susceptible to rupture. Also, stenosis from the inward expansion of the atheroma can result in occlusion of vessels such as the coronaries. However symptomatic disease can be mitigated by exuberant collateral circulation.

The systemic changes detected in atherosclerosis are closely similar in the aorta and the coronary and the carotid arteries. The continuous process of atherosclerosis is typically comprehended as an extended sequence of histologic developments or a series of different classes of lesions that may be visible to the unaided eye.

Staging

There are major histologic changes in the development of atherosclerosis approximately in their order of occurrence.

The Early Fatty Streak Phase

Early fatty streak lesions begin in childhood. The adaptive intimal thickening is present from birth and grows in areas of a high oscillatory shear index where it is characterized by retention of modified lipoproteins in the intima. A characteristic of atherosclerosis-prone areas is an upregulation of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kB), a pivot in the inflammatory cascade. Areas of uniform laminar flow trigger an upregulation of Kruppel-like factor (KLF)-2 and 4 in endothelium resulting in athero-protective endothelium typified by anti-inflammatory and anti-thrombotic phenotype. As the LDL particles leave the blood and enter the arterial intima, they accumulate by being trapped by proteoglycans and are modified. While the modifications of LDL are not elucidated, oxidative modification generating oxidized LDL appears to be an attractive candidate. Modified LDL is taken up by scavenger receptors (SR) such as SRA and CD36 resulting in foam cell formation since cellular cholesterol content does not regulate these SRs. Following endothelial dysfunction induced by LDL, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, among others, there is a deficiency of NO and prostacyclin and/or an increase in plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 (PAI-1) and cell adhesion molecules (CAMs). After that there is increased adhesion of monocytes and lymphocytes. Typically, endothelial dysfunction induced by proinflammatory stimuli may disrupt the endothelial barrier or microtubule function leading to increased junctional permeability manifested by transendothelial migration of immune cells and atherogenic lipoproteins into the arterial intima. Further, the monocytes in intima mature into resident macrophages via macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF), imbibe modified lipids and become foam cells the characteristic feature of the early fatty streak lesion.

Early Fibro Atheroma Phase

Following foam cell formation, there is a migration of smooth muscle cells from the media into the intima under control of angiotensin II, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and insulin-like growth factor (IGF), among others. These cells are crucial in the generation of the collagen-enriched fibrous plaque which is located under the endothelium and is considered the protector of the vessel wall from plaque rupture. Also, lymphocytes via type-1 T-helper (TH1) cells and type-2 T-helper (TH2) cells responses play a role. This, in addition to CAMs like vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), P-Selectin, cytokines like interleukin-1 (IL-1), and chemokines like monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-I), the CD40-CD40L dyad, and other mediators of inflammation plays a role in atherosclerosis.

Advancing Atheroma: Thin-Cap Fibroatheroma and Its Rupture

Advancing atheroma appear at about age 55 to 65 years. Plaque rupture, for example, vulnerable plaques, are dictated by a thin, fibrous cap with low, smooth, muscle cell (SMC) density, abundant lipid, and macrophages, and enriched in tissue factor in the cells. The thin-cap atheroma is surrounded by a necrotic core heavily infested by cholesterol-enriched macrophages, cholesterol crystals and T lymphocytes and susceptible to rupture. The fibrous cap is weakened due to uncontrolled proteolytic enzyme activity, for example, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which expose the intima and produce a thrombus via tissue-factor activation and platelet aggregation that extends into the arterial lumen. This lesion is most frequently known as a vulnerable plaque because of the risk of rupture and life-threatening thrombosis.

Plaque Rupture

This is the region of fibrous cap rupture in which the overlying thrombus interacts with the original necrotic core and is frequently found in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery, followed by the left and right circumflex coronary arteries. The causes of plaque rupture are not well studied, but main factors include expression of enzymes like MMPs, Myeloperoxidase produced by inflammatory cells that weaken the fibrous cap, high-shear arterial regions, macrophage calcification, and iron deposition.

Growth and Development of the Necrotic Core

This is an important pathogenic process contributing to plaque vulnerability. Studies have shown that repeat intraplaque hemorrhage is a contributing feature to necrotic core expansion as red blood cells are enriched with lipids and a rich source of free cholesterol, which is an important constituent of ruptured plaques.

Many studies indicate the role of the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway or unfolded protein response as the chief mechanisms of macrophage cell death in plaques causing accumulation of dead macrophages. Also in comparison to early plaques, microvessel density is increased in advanced plaques by a dysregulated neovascularization. In normal and atherosclerotic arteries microvessels are thin-walled and characterized with poor structural integrity and endothelial junctions. Thus, intraplaque hemorrhage together with the death of macrophages coupled with defective phagocytic clearance is one of the primary reasons behind necrotic core expansion in advance stage. Healed plaque ruptures can be easily detected microscopically by identification of disruptions in the fibrous cap in healed lesions consisting of proteoglycans and/or collagen.

Plaque Erosion

It is widely accepted that thrombi may occur due to plaque rupture, plaque erosion, or, rarely, a calcified nodule. In a study on 20 patients who died of acute myocardial infarction, it was found that 60% of patients had plaque ruptures and the remaining 40% had superficial erosion. Plaque erosion is typically characterized by no endothelium at the site of erosion, minimal inflammation, and the exposed intima mainly composed of smooth muscle cells and proteoglycans.

Morphologically, eroded surfaces contain few macrophages and T lymphocytes. Also, the occurrence of calcification is less common in plaque erosions than ruptures. Most importantly, the thrombi in erosions exhibited late stages of healing, and selective markers such as myeloperoxidase levels were elevated in patients with acute coronary sinus with erosion in comparison to those with rupture indicating specific acute coronary events.

Most of the histologic changes already described above appear as gross plaques that are visible to the naked eye, but the fine histologic changes cannot be distinguished. Atherosclerotic lesions have been differentiated based on gross findings in the aorta.

Gross Findings

Bright yellow, minimally-raised lesions that demonstrate abundant lipid when stained with oil red O are identified as fatty streaks. The homogeneous, white, raised, firmer areas that are relatively well marked are known as fibrous plaques. The ulcerated plaques denote ruptured fibroatheromas and show surface thrombosis. The gross outcomes of carotid plaques are like those of the coronary arteries and calcification is often seen as deposits. Most importantly, similar types of plaques are seen in low-risk and high-risk groups, but shortly after the start of development, fibrous plaques become dominant and progressively expand more rapidly in high-risk groups. Also, patterns of development and growth of fatty streaks and fibrous plaques in women is similar to that in men.

History and Physical

Examination for blood pressure and the peripheral pulses, listening for bruits (carotids and abdomen), pulsatile abdominal masses, heart failure, supra-valvar aortic stenosis, xanthomas.

Evaluation

In the assessment of ASCVD risk factors, measuring the lipid profile (LDL-cholesterol), plasma glucose, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) (in certain instances) is reasonable. Ultrasound of the abdomen to screen for an abdominal aneurysm is indicated in the elderly especially with other ASCVD risk factors. In screening for peripheral artery disease (PAD), a Doppler device is used to obtain the ankle-brachial index (normal 1.0 to 1.40) and is a very useful, cost-effective test to rule out PAD. It needs to be emphasized that PAD is a marker for ASCVD in other beds (coronary artery disease [CAD], cerebrovascular disease, among others). Also, sonography of the carotids to rule out stenosis if a patient has a carotid bruit. An electrocardiogram (ECG) may be useful if indicated, for example, stress ECG. To confirm ASCVD, a reasonable test is the calcium score by electron beam computed tomography (EBCT). It needs to be interpreted according to age. It establishes plaque burden.

Angiography is considered as the primary method for imaging atherosclerotic lesions in the coronary circulation and provided a good measure of the coronary silhouette. However, it is an invasive procedure and should be performed in high-risk patients or those with symptomatology and is not a screening test.

For the noninvasive assessment of ASCVD, computed tomography (CT) angiography is evolving as a promising approach. Moreover, CT angiography can be used to detect the presence of low-attenuated plaques and in predicting future acute coronary events. In addition to CT angiography, new imaging techniques like cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (cardiac MRI) may prove useful in certain patients. However, cost needs to be balanced with need given the burgeoning increasing healthcare costs.

Treatment / Management

The best management of ASCVD is to treat the risk factors such as elevated LDL-C, blood pressure (BP), diabetes, among others. Also, all patients should be encouraged to exercise for 90 to 150 minutes and eat a healthy diet low in saturated (red and processed meat, organ meats, and the like) and trans fats (baked goods), salt intake less than 5 grams per day with enrichment in fiber, monounsaturated fats, fatty fish, fruits, and vegetables. Smokers should be encouraged to stop and be referred to a smoking cessation program.[11][12][13][14](A1)

The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) are the mainstay to lower LDL cholesterol and reduce cardiovascular events and mortality. To control BP, 2 or more drug classes are required including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACEs) inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), diuretics, beta-blockers, and calcium channel blockers (CCB) and vasodilators. It should be emphasized to the patient that good BP control prevents stroke, and desirable BP is less than 130/85. In addition to diet and exercise, there are numerous therapies to manage diabetes. The goal is to keep the glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) below 7%, BP below 130/85, and LDL-cholesterol below 100 mg/dl in primary prevention.

For clinical ASCVD, revascularization procedures are warranted such as angioplasties, bypass, among others. Also, thrombolysis is also a therapeutic option for CVA, acute limb ischemia from a thrombus/embolus.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of ASCVD is legion. It can cause chest pain, dizziness, claudication, and weakness. A good physical examination history and appropriate testing as detailed above can rule out ASCVD manifestations.

Prognosis

The prognosis of ASCVD is very good given the advances in the management of risk factors such as LDL-cholesterol with statin therapy, BP, diabetes, smoking cessation, exercising regularly, and adhering to a prudent diet. The prognosis worsens with a full-blown, end-organ disease such as heart failure, ischemic stroke with paralysis and impaired cognition and gangrene necessitating amputation and rupture of an abdominal aneurysm.

Complications

ASCVD can present as coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease (CVA), transient ischemic attack (TIA), peripheral artery disease (PAD), and abdominal aneurysms, and renal artery stenosis in males. This article has included the management of risk factors and tests required to assess for ASCVD complications. Further details are beyond the purview of this review on atherosclerosis but are detailed in other chapters in this series.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

For the most part atherosclerosis and its pathology can be prevented. All healthcare workers who look after patients should educate patients on the need to exercise regularly, discontinue smoking, maintain a healthy body weight, eat a healthy diet and remain compliant with the medications used to lower lipids. There is ample evidence that these preventive measures can sigificantly reduce the risk of adverse cardiac events and stroke. [15][16]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Dichgans M, Pulit SL, Rosand J. Stroke genetics: discovery, biology, and clinical applications. The Lancet. Neurology. 2019 Jun:18(6):587-599. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30043-2. Epub 2019 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 30975520]

Mohd Nor NS, Al-Khateeb AM, Chua YA, Mohd Kasim NA, Mohd Nawawi H. Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia in a pair of identical twins: a case report and updated review. BMC pediatrics. 2019 Apr 11:19(1):106. doi: 10.1186/s12887-019-1474-y. Epub 2019 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 30975109]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaul S, Lancaster GI, Meikle PJ. Plasmalogens: A potential therapeutic target for neurodegenerative and cardiometabolic disease. Progress in lipid research. 2019 Apr:74():186-195. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2019.04.003. Epub 2019 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 30974122]

Reiss AB, Grossfeld D, Kasselman LJ, Renna HA, Vernice NA, Drewes W, Konig J, Carsons SE, DeLeon J. Adenosine and the Cardiovascular System. American journal of cardiovascular drugs : drugs, devices, and other interventions. 2019 Oct:19(5):449-464. doi: 10.1007/s40256-019-00345-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30972618]

Shafi S, Ansari HR, Bahitham W, Aouabdi S. The Impact of Natural Antioxidants on the Regenerative Potential of Vascular Cells. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2019:6():28. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2019.00028. Epub 2019 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 30968031]

Doodnauth SA, Grinstein S, Maxson ME. Constitutive and stimulated macropinocytosis in macrophages: roles in immunity and in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2019 Feb 4:374(1765):20180147. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2018.0147. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30967001]

Ala-Korpela M. The culprit is the carrier, not the loads: cholesterol, triglycerides and apolipoprotein B in atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. International journal of epidemiology. 2019 Oct 1:48(5):1389-1392. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyz068. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30968109]

Watson M,Dardari Z,Kianoush S,Hall ME,DeFilippis AP,Keith RJ,Benjamin EJ,Rodriguez CJ,Bhatnagar A,Lima JA,Butler J,Blaha MJ,Rifai MA, Relation Between Cigarette Smoking and Heart Failure (from the Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis). The American journal of cardiology. 2019 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 30967285]

Whelton SP, Deal JA, Zikusoka M, Jacobson LP, Sarkar S, Palella FJ Jr, Kingsley L, Budoff M, Witt MD, Brown TT, Post WS. Associations between lipids and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. AIDS (London, England). 2019 May 1:33(6):1053-1061. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002151. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30946159]

Carmona FD, López-Mejías R, Márquez A, Martín J, González-Gay MA. Genetic Basis of Vasculitides with Neurologic Involvement. Neurologic clinics. 2019 May:37(2):219-234. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2019.01.006. Epub 2019 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 30952406]

Perez-Martinez P, Katsiki N, Mikhailidis DP. The Role of n-3 Fatty Acids in Cardiovascular Disease: Back to the Future. Angiology. 2020 Jan:71(1):10-16. doi: 10.1177/0003319719842005. Epub 2019 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 30966756]

Spannella F,Giulietti F,Di Pentima C,Sarzani R, Prevalence and Control of Dyslipidemia in Patients Referred for High Blood Pressure: The Disregarded [PubMed PMID: 30953331]

Esper RJ, Nordaby RA. Cardiovascular events, diabetes and guidelines: the virtue of simplicity. Cardiovascular diabetology. 2019 Mar 28:18(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s12933-019-0844-y. Epub 2019 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 30922303]

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, Himmelfarb CD, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones D, McEvoy JW, Michos ED, Miedema MD, Muñoz D, Smith SC Jr, Virani SS, Williams KA Sr, Yeboah J, Ziaeian B. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019 Sep 10:140(11):e596-e646. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678. Epub 2019 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 30879355]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJukema JW, Szarek M, Zijlstra LE, de Silva HA, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, Diaz R, Edelberg JM, Goodman SG, Hanotin C, Harrington RA, Karpov Y, Moryusef A, Pordy R, Prieto JC, Roe MT, White HD, Zeiher AM, Schwartz GG, Steg PG, ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab in Patients With Polyvascular Disease and Recent Acute Coronary Syndrome: ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019 Sep 3:74(9):1167-1176. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.013. Epub 2019 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 30898609]

Soohoo M,Moradi H,Obi Y,Rhee CM,Gosmanova EO,Molnar MZ,Kashyap ML,Gillen DL,Kovesdy CP,Kalantar-Zadeh K,Streja E, Statin Therapy Before Transition to End-Stage Renal Disease With Posttransition Outcomes. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 30885048]