Introduction

Bacillus cereus is a toxin-producing facultatively anaerobic gram-positive bacterium. The bacteria are commonly found in the environment and can contaminate food. It can quickly multiply at room temperature with an abundantly present preformed toxin. When ingested, this toxin can cause gastrointestinal illness, which is the commonly known manifestation of the disease. Gastrointestinal (GI) syndromes associated with B. cereus include diarrheal illness without significant upper intestinal symptoms and a predominantly upper GI syndrome with nausea and vomiting without diarrhea. B. cereus has also been implicated in infections of the eye, respiratory tract, and wounds. The pathogenicity of B. cereus, whether intestinal or nonintestinal, is intimately associated with the production of tissue-destructive exoenzymes. Among these secreted toxins are hemolysins, phospholipases, and proteases.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

B. cereus is a common bacterium, present ubiquitously in the environment. It has the ability to form spores which allows it to survive longer in extremes of temperature. Consequently, it is found as a contaminant of various foods, i.e., beef, turkey, rice, beans, vegetables. The diarrheal illness is often related to meats, milk, vegetables, and fish. The emetic illness is most often associated with rice products, but it has also been associated with other types of starchy products such as potato, pasta, and cheese. Some food mixtures (sauces, puddings, soups, casseroles, pastries, and salads, have been associated with food-borne illness in general.[3][4]

Bacillus cereus is caused by the ingestion of food contaminated with enterotoxigenic B. cereus or the emetic toxin. In non-gastrointestinal illness, reports of respiratory infections similar to respiratory anthrax have been attributed to B. cereus strains harboring B. anthracis toxin genes.

Epidemiology

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) website states that there were 619 confirmed outbreaks of Bacillus-related poisoning from 1998 through 2015, involving 7385 illnesses. In this timeframe, there were 75 illnesses and three deaths due to confirmed Bacillus-related illnesses. The website states that there were 19,119 outbreaks overall and 373,531 illnesses. It refers to 14,681 hospitalizations and 337 deaths during this timeframe. These statistics refer to all Bacillus-related illnesses, and not just B. cereus related illnesses.[5][6]

The FDA "Bad Bug Book" further breaks this down and states that there are an estimated 63,400 episodes of B. cereus illness annually in the United States. From 2005 to 2007, there were 13 confirmed outbreaks and 37.6 suspected outbreaks involving over 1000 people.

Everyone is susceptible to B. cereus infection; however, mortality related to this illness is rare. The emetic enterotoxin has been associated with a few cases of liver failure and death in otherwise healthy people. The infective dose or the number of organisms most commonly associated with human illness is 10^5 to 10^8 organisms/gram, but pathogenicity arises from the preformed toxin, not the bacteria themselves.

Pathophysiology

The pathogenicity of B. cereus, whether inside or outside the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, is associated with exoenzyme production. Among the secreted toxins are four hemolysins, three distinct phospholipases, and three pore-forming enterotoxins. The enterotoxins which activate the nod-like receptor protein-3 (NLRP3) are hemolysin BL (HBL), nonhemolytic enterotoxin (NHE), and cytotoxin K. In the small intestine, vegetative cells, ingested as viable cells or spores, produce and secrete a protein enterotoxin and induce a diarrheal syndrome. Cereulide is a plasmid-encoded cyclic peptide, which is produced in food products and ingested as a formed toxin. In rabbit ligated ileal-loop assays, culture filtrates of enterotoxigenic strains induced fluid accumulation and hemolytic, cytotoxic, dermonecrosis, and increased vascular permeability in rabbit skin.[7] The enterotoxin is composed of a binding component (B) and two hemolytic components, designated HBL. In the diarrheal form of the disease, a nonhemolytic three-component enterotoxin, designated NHE, has been identified. The non-hemolytic enterotoxin (NHE) from Bacillus cereus activates the nod-like receptor protein-3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and pyroptosis. This leads to programmed cell death initiated by the activation of inflammatory caspases of the infected tissue.[8]

Histopathology

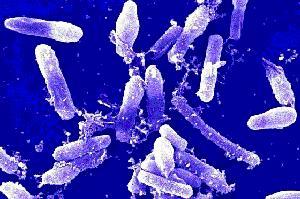

B. cereus is a catalase-positive, facultatively anaerobic, spore-forming gram-positive bacilli. However, it can appear Gram variable in some cases. On blood and chocolate agar Gram staining, B. cereus has a uniform bacillary appearance. Their size ranges from 3 x 0.4 microns to 9 x 2 microns. Colonies of B. cereus have an irregular perimeter and are opaque on sheep blood agar. When grown on an egg yolk agar, a zone of opacification will be noted due to lecithinase production. In body fluids, it appears straight or slightly curved. It can appear alone or in short chains on body fluid gram stains. B. cereus appearance in tissue sections can show long and filamentous organisms. See Image. Bacillus Cereus Rods. Clear spores may or may not be present.

History and Physical

Clinical manifestations of B. cereus infection can be categorized as gastrointestinal disease syndromes or extra-gastrointestinal infections. Gastrointestinal syndromes are further divided into two types of illnesses, i.e., diarrheal syndrome and emetic syndrome.

Gastrointestinal Syndromes

For diarrheal-type illnesses, symptoms include profuse watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, and cramping. Nausea and vomiting are seldom seen. Symptom onset is usually within 6 to 15 hours of eating food left at room temperature for more than 2 hours. The toxin associated with this form of the illness is produced in the small intestine of the patient after ingestion of the bacilli or the spores. Pore-forming cytotoxins (hemolysin BL, nonhemolytic enterotoxin, and cytotoxin K) are secreted by the ingested vegetative cells. These toxins are heat-labile.

For emetic-type illnesses, symptoms include nausea and vomiting, similar to the presentation associated with Staphylococcus aureus food-borne illness. Diarrhea may be present in some individuals as well. Symptom onset is generally within 30 minutes to 6 hours of consuming rice or starchy foods left at room temperature, even after being reheated. This illness is due to the presence of cereulide, an ionophoric low-molecular-weight dodecadepsipeptide that is pH-stable and resistant to heat and proteases.

Symptoms for both types usually resolve within 24 hours after onset.

Extra-gastrointestinal Syndromes

The ubiquitous presence of B. cereus in the environment makes it a potential organism for infection when direct penetrating injuries or hematologic access is present. Risk factors for complicated and severe disease include immunosuppression, intravenous drug abuse, and the neonatal period. The association of intravenous drug use and extraintestinal B. cereus infections is related to the use of contaminated needles and drug specimens. Patients with an indwelling venous catheter or a traumatic/surgical wound are at increased risk of complicated infections by this organism.

Endophthalmitis is a vision-threatening eye infection resulting from microbial infection of the inner eye. This is the most common extraintestinal manifestation of this disease. The hallmark ophthalmic lesion is a corneal ring abscess, which may be accompanied by rapid progression of pain, proptosis, chemosis, retinal hemorrhage, and perivasculitis. Systemic manifestations include fever, leukocytosis, and generalized malaise. Ocular trauma with penetrating injury is the most common cause of this infection.

Bacteremia and endocarditis can also occur with this infection. True B. cereus bacteremia can occur with intravenous drug use, central venous access catheters, or mucosal injuries/compromise in patients with neutropenia. Patients with immunosuppression, particularly those with underlying hematologic malignancies, are at high risk for this type of infection with bacillus species. Patients with bacillus bacteremia often present with alteration of consciousness and have secondary nervous system involvement. Endocarditis with bacillus species is usually associated with intravenous drug use, central venous catheters, or the presence of intracardiac hardware such as prophetic valves and/or pacemakers.

Soft tissue and bone infections can occur with penetrating trauma or mucosal injury. These include gunshot wounds, open fractures, animal bites, and burn wounds, to name a few. Cellulitis and necrotizing soft tissue infection can also occur. B. cereus can also cause superimposed infection of chronic osteomyelitis sites.

Keratitis secondary to B. cereus infection can occur due to corneal abrasions, including those secondary to contact lens use.

Evaluation

B. cereus can be confirmed as the source of a foodborne outbreak by (1) isolation of strains of the same serotype from a food source and the feces or vomitus of a patient, (2) isolation of large numbers of B. cereus serotype known to cause foodborne illness from the food/feces/vomitus of a patient, or (3) isolation of B. cereus from suspect foods and confirmation of the enterotoxin through serology (for the diarrheal toxin) or biological tests (diarrheal and emetic).

In extraintestinal infections, evaluation is made with body fluid analysis. For example, the diagnosis of endophthalmitis can be made by the gram-staining of vitreous fluid.

It is important to note that bacillus species in blood cultures is often considered a contaminant. In the correct clinical setting, this should be regarded as true bacteremia rather than contamination.

Treatment / Management

B. cereus infection is usually self-limited and does not require any targeted therapy. Treatment for most patients is symptomatic care with oral hydration. Most patients recover within 24 hours after symptom onset. Empiric antibiotic therapy for gastrointestinal syndromes secondary to B. cereus infections is not indicated. In severe cases, intravenous fluid hydration may be necessary.[9][10][11] (B3)

The majority of severe and systemic illnesses are caused by ocular infections by this organism. B. cereus ocular infections can rapidly destroy an infected eye, especially in penetrating trauma with a foreign body. In suspected cases, rapid therapeutic intervention is mandatory irrespective of the results of immediate diagnostic testing. The outcome varies with the microbial agent involved and the rapidity of and response to treatment. B. cereus produces beta-lactamases and is resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics. When antibiotics are required, treatment with vancomycin, gentamicin, chloramphenicol, or carbapenems should be considered. Clindamycin, tetracycline, and erythromycin have had variable results with susceptibility testing and are not considered first-line agents. A 2007 study testing susceptibility of Bacillus species to various antibiotics reported universal resistance to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and beta-lactam antibiotics by various B. cereus species. Some were clindamycin and erythromycin resistant as well. According to this study, all Bacillus isolates were susceptible to chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, gatifloxacin, gentamicin, levofloxacin, linezolid, moxifloxacin, rifampicin, streptomycin, tetracycline, tigecycline, and vancomycin.[12] In severe cases with risk of systemic infection, simultaneous therapy via multiple routes, i.e., intravenous and intraocular, may be required.[13]

Differential Diagnosis

- Viral infections (e.g., Rotavirus)

- Bacterial infections (e.g., Campylobacter, Shigella, Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Yersinia enterocolitica, Vibrio cholerae, Clostridium difficile)

- Parasitic infections (e.g., Giardia, Cryptosporidium, Entameba, Microsporidium, Cyclospora)

- Toxins (Staphylococcus aureus)

- Appendicitis

- Diverticulitis

- Mesenteric ischemia

Prognosis

Patients on systemic corticosteroids, those who are hospitalized, and those with neutropenia have a poor prognosis when combined with B. cereus bacteremia. Patients with hematologic malignancies and neutropenia, along with B. cereus infections, have a worse prognosis, which improves with the resolution of neutropenia.[14] A case series of patients with underlying hematologic malignancies and B. cereus bacteremia noted primary symptom presentation to be neurologic symptoms rather than gastrointestinal. Moreover, they noted these infections to be related to central venous catheters. Of the 12 patients in this case series, four died of B. cereus septicemia. They noted delayed initiation of appropriate antibiotics, liver dysfunction, and evidence of central nervous system involvement with a poor and fatal prognosis.[15] B. cereus infection in the neonatal period has been associated with a poor outcome despite timely antibiotic therapy.

Complications

Complications of gastrointestinal syndromes associated with B. cereus infections are uncommon and only occur in people with compromised immune systems. Complications in patients with extraintestinal infections include gangrene, cellulitis, aseptic meningitis, septicemia, and death.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated about the importance of handwashing for the prevention of these bacterial infections. Also, they should be provided with the necessary literature regarding the appropriate receiving, handling, processing, and storage of food and food products in order to prevent the infection.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bacillus cereus infection is a relatively common infection. In the majority of the cases, infections are self-limited with no complications and do not require any treatment other than supportive care. However, B. cereus infections can become severe in immunocompromised patients and those with a direct infection of ocular tissue after penetrating trauma. These cases can rapidly progress to permanent vision loss, septicemia, and even death. Prompt recognition and a high degree of suspicion are required to improve outcomes. The clinical pharmacists can assist the medical team by assuring the appropriate selection of antibiotics as B. cereus is naturally resistant to two major classes of antibiotics. The critical care nurse can help minimize these infections in immunocompromised individuals by promptly removing indwelling central venous catheters. For mild cases, the nurse plays a vital role in educating patients on the appropriate food storage to prevent outbreaks. Care coordination between nurses, pharmacists, and medical providers will decrease the incidence of this disease and improve outcomes for critically ill patients.[Level 5]

Media

References

Nguyen AT, Tallent SM. Screening food for Bacillus cereus toxins using whole genome sequencing. Food microbiology. 2019 Apr:78():164-170. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2018.10.008. Epub 2018 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 30497598]

Hölzel CS, Tetens JL, Schwaiger K. Unraveling the Role of Vegetables in Spreading Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria: A Need for Quantitative Risk Assessment. Foodborne pathogens and disease. 2018 Nov:15(11):671-688. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2018.2501. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30444697]

Kimura 木村 啓太郎 K, Yokoyama 横山 智 S. Trends in the application of Bacillus in fermented foods. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2019 Apr:56():36-42. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2018.09.001. Epub 2018 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 30227296]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOmer MK, Álvarez-Ordoñez A, Prieto M, Skjerve E, Asehun T, Alvseike OA. A Systematic Review of Bacterial Foodborne Outbreaks Related to Red Meat and Meat Products. Foodborne pathogens and disease. 2018 Oct:15(10):598-611. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2017.2393. Epub 2018 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 29957085]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMay FJ, Polkinghorne BG, Fearnley EJ. Epidemiology of bacterial toxin-mediated foodborne gastroenteritis outbreaks in Australia, 2001 to 2013. Communicable diseases intelligence quarterly report. 2016 Dec 24:40(4):E460-E469 [PubMed PMID: 28043220]

Thein CC, Trinidad RM, Pavlin BI. A large foodborne outbreak on a small Pacific island. Pacific health dialog. 2010 Apr:16(1):75-80 [PubMed PMID: 20968238]

Beecher DJ, Wong AC. Improved purification and characterization of hemolysin BL, a hemolytic dermonecrotic vascular permeability factor from Bacillus cereus. Infection and immunity. 1994 Mar:62(3):980-6 [PubMed PMID: 8112873]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFox D, Mathur A, Xue Y, Liu Y, Tan WH, Feng S, Pandey A, Ngo C, Hayward JA, Atmosukarto II, Price JD, Johnson MD, Jessberger N, Robertson AAB, Burgio G, Tscharke DC, Fox EM, Leyton DL, Kaakoush NO, Märtlbauer E, Leppla SH, Man SM. Bacillus cereus non-haemolytic enterotoxin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nature communications. 2020 Feb 6:11(1):760. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14534-3. Epub 2020 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 32029733]

Meldrum RJ, Little CL, Sagoo S, Mithani V, McLauchlin J, de Pinna E. Assessment of the microbiological safety of salad vegetables and sauces from kebab take-away restaurants in the United Kingdom. Food microbiology. 2009 Sep:26(6):573-7. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2009.03.013. Epub 2009 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 19527831]

Zhou G, Liu H, He J, Yuan Y, Yuan Z. The occurrence of Bacillus cereus, B. thuringiensis and B. mycoides in Chinese pasteurized full fat milk. International journal of food microbiology. 2008 Jan 31:121(2):195-200 [PubMed PMID: 18077041]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWarburton DW, Harrison B, Crawford C, Foster R, Fox C, Gour L, Purvis U. Current microbiological status of 'health foods' sold in Canada. International journal of food microbiology. 1998 Jun 30:42(1-2):1-7 [PubMed PMID: 9706793]

Luna VA, King DS, Gulledge J, Cannons AC, Amuso PT, Cattani J. Susceptibility of Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus mycoides, Bacillus pseudomycoides and Bacillus thuringiensis to 24 antimicrobials using Sensititre automated microbroth dilution and Etest agar gradient diffusion methods. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2007 Sep:60(3):555-67 [PubMed PMID: 17586563]

Drobniewski FA. Bacillus cereus and related species. Clinical microbiology reviews. 1993 Oct:6(4):324-38 [PubMed PMID: 8269390]

Nakashima M, Osaki M, Goto T, Kagaya Y, Kawashima N, Morishita T, Ozawa Y, Miyamura K. [Bacillus cereus bacteremia in patients with hematological disorders]. [Rinsho ketsueki] The Japanese journal of clinical hematology. 2021:62(3):157-162. doi: 10.11406/rinketsu.62.157. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33828007]

Uchino Y, Iriyama N, Matsumoto K, Hirabayashi Y, Miura K, Kurita D, Kobayashi Y, Yagi M, Kodaira H, Hojo A, Kobayashi S, Hatta Y, Takeuchi J. A case series of Bacillus cereus septicemia in patients with hematological disease. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2012:51(19):2733-8 [PubMed PMID: 23037464]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence