Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Biceps Muscle

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Biceps Muscle

Introduction

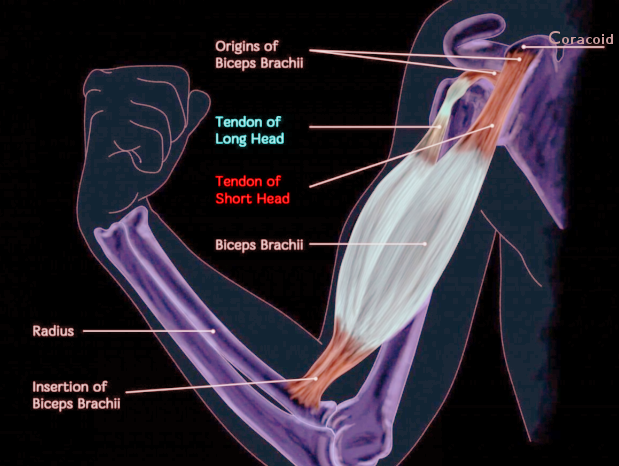

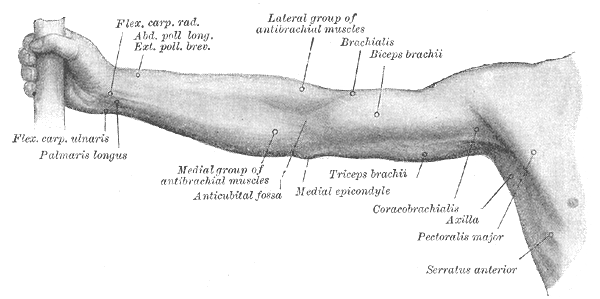

The biceps brachii, or simply "biceps," is a large, thick, fusiform muscle on the upper arm's ventral portion (see Image. Right Upper Extremity Surface Anatomy). As the name implies, this muscle's proximal attachment has 2 heads. The short head is sometimes referred to as "caput breve," while the long head is also called "caput longum." Distally, the biceps brachii continues as the bicipital aponeurosis, crossing the elbow joint to insert on the radius and forearm fascia. This muscle is a forearm flexor when extended but becomes the forearm's most powerful supinator when flexed.

The conditions affecting the biceps brachii are often caused by muscle overuse or trauma. For example, the "popeye deformity," common to baseball pitchers, arises from a ruptured long head tendon due to chronic wear and tear. Consequently, the muscle forms a ball at the anterior mid-arm. The biceps brachii is also an important landmark for locating the brachial artery during physical examination and ultrasound-guided arterial cannulation.

This article discusses the biceps brachii's anatomy and clinical importance.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Structure

The long head of the biceps brachii tendon originates at the supraglenoid tubercle and superior glenoid labrum. The long head's labral origin is mostly posterior in most individuals, while the tendon is 9 cm long on average. The tendon is extrasynovial inside the shoulder joint, passing obliquely toward the bicipital groove. The biceps long head tendon then exits the distal bicipital groove and joins the short head tendon. Both tendons transition into their respective muscle bellies in the central third of the upper arm.[1][2] After crossing the cubital fossa, the biceps brachii continues as the bicipital aponeurosis, which inserts on the radial tuberosity and medial forearm fascia (see Image. Biceps Brachii Anatomy).[3]

The biceps' distal insertion point has become controversial in recent years due to the site's importance in distal biceps reconstruction. Historically, the insertion site has been described as having one homogenous tendon attached to the radial tuberosity. However, recent studies reveal that the biceps inserts distally via 2 distinct tendons. The short head inserts more distally than the long head, specifically at the radial tuberosity's apex. The long head passes deep to the short head's distal tendon before attaching proximally on the radial tuberosity.[4]

The muscle antagonizing the biceps is the triceps brachii.[5][6][7]

Biomechanics

The biceps brachii is primarily a strong forearm supinator but a weak elbow flexor.[8] The brachialis is the primary forearm flexor. Biomechanically, the long head of the biceps has a controversial role in the shoulder joint's dynamic stability. However, studies demonstrate that the long head tendon may be a passive stabilizer of the shoulder joint.

Neer proposed in the 1970s that the shoulder-stabilizing action of the tendon of the biceps long head varied depending on the elbow's position. Subsequent studies refuted the theory that the long head had an active role in securing the joint.[9] Jobe and Perry evaluated biceps activation during the throwing motion in athletes. The authors reported that peak muscle stimulation occurred during elbow flexion and forearm deceleration, while little proximal biceps activity occurred during the earlier phases of throwing.[10]

Pain Generation

The long head of the biceps tendon is a well-recognized source of anterior shoulder pain. Mechanical causes include repetitive traction, friction, and glenohumeral rotation. The bicipital sheath is vulnerable to tenosynovial inflammation by association as it is contiguous with the glenohumeral joint's synovial lining. The upper third of the long head tendon possesses a rich sympathetic nerve network. Neuropeptides like substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide are released abundantly in the sensory nerves in this region. This sympathetic network causes vasodilatory changes, contributing to neurogenic inflammation that leads to chronic damage to the biceps long head tendon.[11][12]

Embryology

The limb muscles' cellular precursors migrate into the limb buds from the somites in the 5th week of development. The muscle fibers arise from the somites, while the local limb bud cells form the tendons and other connective muscle tissue. Myocyte formation occurs shortly after the skeletal elements develop.

The biceps, coracobrachialis, and brachialis muscles arise from a common premuscular mass. The proximal insertions of the biceps brachii's 2 heads separate with scapular development. The brachialis and biceps may be hard to distinguish until the distal segment of the common muscle mass differentiates, which occurs later than proximal muscle segmentation.[19][20]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The primary arterial blood supply for the biceps brachii muscle comes from the muscular branches of the brachial artery. This artery is the axillary artery's continuation as it exits the axilla at the teres major's inferior margin. The brachial artery can be palpated deep to the biceps. Locating this vessel before taking the blood pressure helps ensure that the appropriate cuff pressure is applied and the measurement is accurate.[13]

Nerves

The musculocutaneous nerve provides the biceps' sensory and motor innervation. This nerve arises from the C5 and C6 spinal roots and is a terminal branch of the brachial plexus' lateral cord. The musculocutaneous nerve runs from the inferior border of the pectoralis minor, pierces the coracobrachialis, and traverses distally between the biceps and brachialis. This nerve becomes the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm after crossing the cubital fossa.

Physiologic Variants

Approximately 30% of adults have some variation in the biceps' origin. A third head may arise from the humerus in many patients. However, about 2% to 5% of individuals may have supernumerary heads of the biceps, numbering anywhere from 3 to 7.[14] The distal biceps tendon may be bifurcated in about 20% or completely separated in about 40% of individuals. These variations have no adverse effect on arm function.[15]

Surgical Considerations

The tendon of the biceps long head is enclosed by a synovial sheath and moves back and forth in the bicipital groove during arm movement. This mechanism is a frequent cause of long head tendon inflammation. The procedures commonly performed to treat advanced tendinopathy of the biceps long head are tenotomy and tenodesis.

Biceps Tenotomy

Arthroscopic inspection helps estimate the severity of biceps tendon injury. The Lafosse grading scale can help classify gross biceps long head tendon pathology intraoperatively, which has the following system:[16]

- Grade 0: Normal tendon

- Grade 1: Minor lesion (partial, localized areas of tendon erosion or fraying; focal areas affecting <50% of the tendon width)

- Grade 2: Major lesion (extensive tendon loss, compromising more than 50% of the tendon width)

Some surgeons solely debride tendons with 25% to 50% injury. Arthroscopic biceps tenotomy is indicated for more severe pathology and is performed by releasing the tendon as close as possible to the superior labrum. The tendon should retract distally toward the bicipital groove if unimpeded by soft tissue adhesions. If adhesions are present, the tendon must be mobilized to enable retraction following tenotomy. Potential sources of postoperative pain are hypertrophy of the biceps long head tendon and scarring of other structures in the shoulder joint.[17]

Biceps Tenodesis

This procedure is recommended over tenotomy in the presence of biceps long head tendon instability. Biceps tenodesis is preferred in younger patients, athletes, laborers, and patients specifically concerned with postoperative cosmetic deformities, such as the popeye deformity. Tenodesis optimizes the length-tension relationship of the biceps muscle and reduces the risk of postoperative muscle atrophy, fatigue, and cramping.[18]

Clinical Significance

Pathologic conditions affecting the proximal and distal biceps brachii tendons are often nonoperatively managed initially. Conditions affecting the distal biceps brachii tendon are beyond the scope of this article. Rehabilitation focuses on restoring muscle balance across the shoulder girdle and improving shoulder range of motion, rotator cuff strength, and periscapular stability.

For conditions affecting the proximal aspect of the long head of the biceps tendon, the following treatments can be considered:

- Physical therapy with proximal biceps stretching and strengthening exercises

- Pharmacologic treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Iontophoresis, eg, with dexamethasone

Focused stretching of the anterior shoulder structures, including pectoralis minor, should also be considered. Modalities like dry needling have shown promise in preliminary animal studies. Surgery is warranted in severe or refractory conditions.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Right Upper Extremity Surface Anatomy. This anterior view shows the surface markings of the flexor carpi radialis, abductor and exterior pollicis longus and brevis, palmaris longus, medial antebrachial muscles, antecubital fossa, lateral antebrachial muscles, brachialis, biceps brachii, triceps brachii, and medial epicondyle.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hutchinson HL, Gloystein D, Gillespie M. Distal biceps tendon insertion: an anatomic study. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2008 Mar-Apr:17(2):342-6 [PubMed PMID: 17931901]

Eames MH, Bain GI, Fogg QA, van Riet RP. Distal biceps tendon anatomy: a cadaveric study. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2007 May:89(5):1044-9 [PubMed PMID: 17473142]

Frank RM, Cotter EJ, Strauss EJ, Jazrawi LM, Romeo AA. Management of Biceps Tendon Pathology: From the Glenoid to the Radial Tuberosity. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2018 Feb 15:26(4):e77-e89. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00085. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29337716]

van den Bekerom MP, Kodde IF, Aster A, Bleys RL, Eygendaal D. Clinical relevance of distal biceps insertional and footprint anatomy. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 2016 Jul:24(7):2300-7. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-3322-9. Epub 2014 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 25231429]

Créteur V, Madani A, Sattari A, El Kazzi W, Bianchi S. Ultrasonography of Complications in Surgical Repair of the Distal Biceps Brachii Tendon. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2019 Feb:38(2):499-512. doi: 10.1002/jum.14707. Epub 2018 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 30027585]

Saluja S, Das SS, Kumar D, Goswami P. Bilateral Three-headed Biceps Brachii Muscle and its Clinical Implications. International journal of applied & basic medical research. 2017 Oct-Dec:7(4):266-268. doi: 10.4103/ijabmr.IJABMR_339_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29308368]

Moore CW, Rice CL. Rare muscular variations identified in a single cadaveric upper limb: a four-headed biceps brachii and muscular elevator of the latissimus dorsi tendon. Anatomical science international. 2018 Mar:93(2):311-316. doi: 10.1007/s12565-017-0408-8. Epub 2017 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 28685367]

Busconi BB, DeAngelis N, Guerrero PE. The proximal biceps tendon: tricks and pearls. Sports medicine and arthroscopy review. 2008 Sep:16(3):187-94. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e318183c134. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18703980]

Neer CS 2nd. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder. 1972. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2005 Jun:87(6):1399 [PubMed PMID: 15930554]

Jobe FW, Moynes DR, Tibone JE, Perry J. An EMG analysis of the shoulder in pitching. A second report. The American journal of sports medicine. 1984 May-Jun:12(3):218-20 [PubMed PMID: 6742305]

Alpantaki K, McLaughlin D, Karagogeos D, Hadjipavlou A, Kontakis G. Sympathetic and sensory neural elements in the tendon of the long head of the biceps. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2005 Jul:87(7):1580-3 [PubMed PMID: 15995126]

Mazzocca AD, McCarthy MB, Ledgard FA, Chowaniec DM, McKinnon WJ Jr, Delaronde S, Rubino LJ, Apolostakos J, Romeo AA, Arciero RA, Beitzel K. Histomorphologic changes of the long head of the biceps tendon in common shoulder pathologies. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2013 Jun:29(6):972-81. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.02.002. Epub 2013 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 23571131]

Alexander JG, de Fúcio Lizardo JH, da Silva Baptista J. Multiple arterial variations in the upper limb: description and clinical relevance. Anatomical science international. 2021 Mar:96(2):310-314. doi: 10.1007/s12565-020-00569-5. Epub 2020 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 32909194]

Benes M, Kachlik D, Lev D, Kunc V. Accessory heads of the biceps brachii muscle: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of anatomy. 2022 Aug:241(2):461-477. doi: 10.1111/joa.13666. Epub 2022 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 35412670]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEl Abiad JM, Faddoul DG, Baydoun H. Case report: Broad insertion of a large subscapularis tendon in association with congenital absence of the long head of the biceps tendon. Skeletal radiology. 2019 Jan:48(1):159-162. doi: 10.1007/s00256-018-2989-2. Epub 2018 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 29948038]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLafosse L, Reiland Y, Baier GP, Toussaint B, Jost B. Anterior and posterior instability of the long head of the biceps tendon in rotator cuff tears: a new classification based on arthroscopic observations. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2007 Jan:23(1):73-80 [PubMed PMID: 17210430]

Martetschläger F, Tauber M, Habermeyer P. Injuries to the Biceps Pulley. Clinics in sports medicine. 2016 Jan:35(1):19-27. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2015.08.003. Epub 2015 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 26614466]

Kongmalai P. Arthroscopic extra-articular suprapectoral biceps tenodesis with knotless suture anchor. European journal of orthopaedic surgery & traumatology : orthopedie traumatologie. 2019 Feb:29(2):493-497. doi: 10.1007/s00590-018-2301-0. Epub 2018 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 30145670]