Introduction

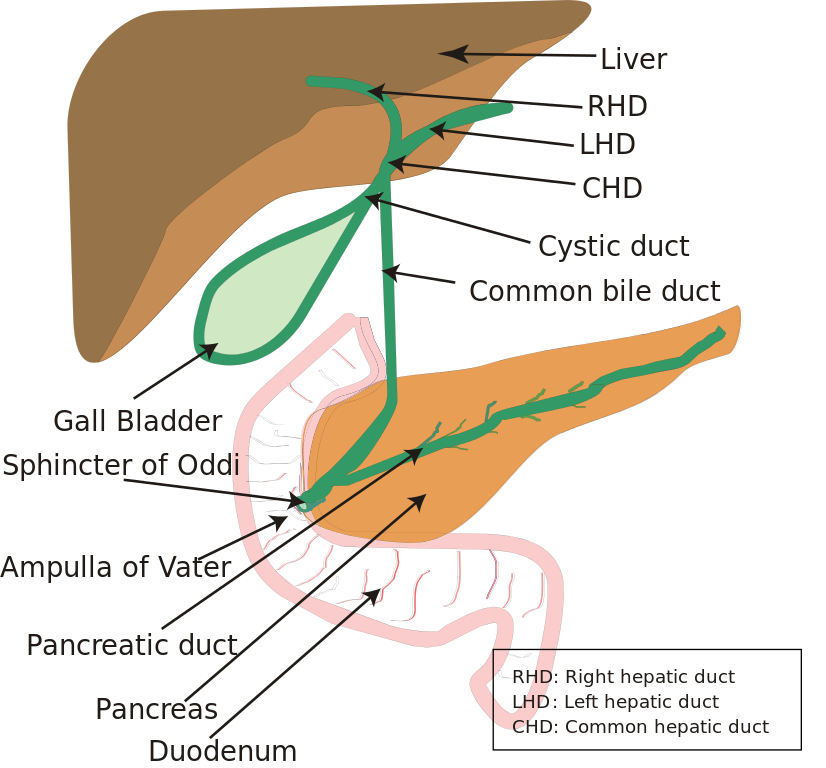

The biliary system refers to bile production, storage, and secretion via the liver, gallbladder, and bile ducts. Bile ducts are categorized into intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts (see Image. Diagram of the Biliary System). Intrahepatic bile ducts include the left and right hepatic ducts, which join to form the common hepatic duct (CHD), while extrahepatic bile ducts include the common bile duct (CBD), which is formed from the CHD and cystic duct. The CBD and pancreatic duct converge to form the ampulla of Vater, which bile travels through before passing through the sphincter of Oddi and into the second portion of the duodenum.[1]

Initially, bile is a unique alkaline (7.5 to 8.1 pH) fluid secreted by hepatocytes (600-1000 mL/day), further altered and refined by the epithelial cells lining the biliary tract, and becoming acidic in the gallbladder (5.2 to 6.0 pH).[2] The gallbladder stores this fluid, where it gets concentrated and subsequently released into the digestive tract via the CBD. On receiving stimulation via the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK) from the intestinal tract due to the presence of food in the intestinal lumen, the gallbladder contracts and secretes bile into the duodenum. The composition of bile is predominantly water with multiple dissolved substances, including cholesterol, amino acids, enzymes, vitamins, heavy metals, bile salts, bilirubin, and phospholipids.[3]

Cellular Level

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Cellular Level

Hepatocytes have specific transporters on their apical and basolateral membranes that play a central role in synthesizing canalicular bile, of which there are two components: bile acid-dependent canalicular fraction and bile acid-independent canalicular fraction. There is a direct correlation between the quantity of bile acid secreted into bile and the amount of water osmotically driven into the bile. Due to the enterohepatic circulation and re-secretion of specific bile acids such as ursodeoxycholic acid, these bile acids have higher choleretic activity and contribute to generating a larger volume of bile.[4]

Three primary transporters on the basolateral membrane of the hepatocytes facilitate sinusoidal uptake of the bile acids, the most important being a sodium-dependent transporter termed the sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP). The sodium-independent transporter is the organic anion-transporting polypeptide (OATP) that brings in the bile acids in exchange for molecules such as bicarbonate and glutathione. Another sodium-independent bile acid transporter is the organic solute and steroid (OST-alpha/OST-beta) transporter, which works to remove bile acid from the hepatocytes in cases of excess bile acid accumulation.[5]

For the secretion of bile acids, there are specific transporters on the canalicular membrane of the hepatocytes. For instance, the ATP-dependent bile acid efflux gets carried by the bile salt export pump (BSEP). In addition, there is apical ATP binding cassette (ABC) transporters, including multidrug resistance-P glycoprotein 3 (MDR3) for phospholipids, MDR1 for lipophilic cationic drugs, multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2) for non-bile acid organic anions, and the protein ABCG5/G8 for the secretion of cholesterol and other sterols.[6]

The cells lining the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary ducts are called cholangiocytes. Their primary role is to alter and refine the contents of the hepatically synthesized bile via a complex mechanism controlled by many molecules, hormones, and neurotransmitters.[7] For example, secretin receptors on the cholangiocytes, when stimulated, increase the bicarbonate secretion in the bile. Other hormones, such as acetylcholine (ACh) and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), increase the biliary bicarbonate secretion, whereas the hormones dopamine, somatostatin, and gastrin inhibit the secretin-stimulated efflux of bicarbonate in the bile.[4] Neurohormonal mechanisms control biliary tract motility via the hormone cholecystokinin, the vagus, and splanchnic nerves. This neurohormonal regulation allows for integrating the gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi motility with the fasting and digestive phases of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Composition of Bile

In order of abundance: water, bile salts, fatty acids, cholesterol, bilirubin, lecithin, and plasma electrolytes (sodium, chloride, bicarbonate, potassium, and calcium).

- Bile pigments[8]

- Biliverdin (green pigment)

- A byproduct of hemoglobin breakdown.

- Converted to unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin via biliverdin-reductase.

- Bilirubin (yellow pigment)

- Unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin is lipid soluble, meaning it cannot be filtered by the glomerulus and is not typically found in the urine.

- Undergoes conjugation within the liver via UDP glucuronyl transferase.

- Conjugated (direct) bilirubin is water soluble, which can be filtered by the glomerulus and may appear in the urine.

- Within the intestine, glucuronic acid is removed by gut bacteria, forming urobilinogen.

- 80% of urobilinogen is excreted in the feces as stercobilin.

- 2% of urobilinogen is excreted in the urine as urobilin.

- Approximately 18% of urobilinogen is reabsorbed into the enterohepatic circulation and delivered back to the liver.

- Biliverdin (green pigment)

- Bile acids[9]

- Primary bile acids: cholic acid, chenodeoxycholic acid

- Synthesized in the liver from cholesterol.

- Conjugated to glycine or taurine to form bile salts.

- Concentrated and stored in the gallbladder during fasting.

- Released into the intestine in response to dietary fat.

- Secondary bile acids: deoxycholic acid, lithocholic acid

- Synthesized from primary bile acids via interaction with intestinal bacteria.

- Reabsorbed in the ileum and colon into the enterohepatic circulation and then transported back to the liver.

- Minimally lost in feces.

- Primary bile acids: cholic acid, chenodeoxycholic acid

- Bile salts[10]

- As previously mentioned, the precursor to bile salts is cholesterol.

- Within the liver, cholesterol is synthesized into bile acids, which are then conjugated with either glycine or taurine to form bile salts.

- The cholesterol precursor is taken from the diet or synthesized in the liver during fat metabolism.

- Most (95%) bile salts are absorbed in the terminal ileum.

- Essential functions of bile salts

- Aid in the absorption of fatty acids, monoglycerides, and, most importantly, cholesterol.

- Bile salts provide the only primary method of cholesterol excretion. They do this by forming small physical complexes with lipids, called micelles, which are taken to the intestinal mucosa, where they are absorbed into the blood.

- Without bile salts, 40% of ingested fats would be lost in the feces, and a metabolic deficit would occur due to this nutrient loss.

- Bile salts have a potent antibacterial effect, as they play an essential role in determining the microbial ecology of the intestine. Alterations in the intestinal levels of bile salts can lead to increased colonization by pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus.[11]

Development

Derived from the ventral foregut endoderm, the biliary tract begins to form during the fourth week of embryonic development. Between weeks four and eight, the extrahepatic bile ducts develop via the lengthening of the caudal portion of the hepatic diverticulum. Around the 8th week of gestation, the cranial portion of the ventral foregut endoderm gives rise to the intrahepatic bile ducts, while the caudal portion gives rise to the development of the extrahepatic biliary tree.[12] The gallbladder and cystic duct form from a ventral outpouching of the bile ducts.

Organ Systems Involved

The organ systems involved in biliary tract physiology are the hepatobiliary, gastrointestinal, and hematologic systems. The breakdown of the hemoglobin stored in the red blood cells occurs in the reticuloendothelial system to form unconjugated bilirubin, which is then transported in the blood attached to albumin. Once this bilirubin enters hepatocytes, it undergoes conjugation via the enzyme UDP glucuronyl transferase and is subsequently secreted in the bile. The bile then passes through the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts to the gallbladder for storage. The bile is secreted into the duodenum and regulated by various hormones. In the intestines, the conjugated bilirubin is converted into urobilinogen, urobilin, and stercobilin. Due to the enterohepatic circulation, most bile salts are then reabsorbed back into the liver.

Two venous plexuses are responsible for draining the biliary tract: the epicholedochal and the paracholedochal venous plexus. The epicholedochal venous plexus is found on the wall of the bile ducts and empties into the paracholedochal venous plexus (PVP). The PVP is connected to the posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein, gastrocolic trunk, right gastric vein, superior mesenteric vein inferiorly, and intrahepatic portal vein branches superiorly.[13]

Function

Bile has many important functions throughout the body, as discussed below.[3]

- Bile is the major excretory route for potentially harmful exogenous lipophilic substances and other endogenous substrates, such as bilirubin and bile salts, which cannot be filtered or excreted by the kidney. Bile aids in emulsifying large fat particles into many minute particles, the surface of which can then be attacked by lipase enzymes secreted in pancreatic juice.

- Bile is the primary route for the elimination of cholesterol.

- Bile protects the organism from enteric infections by excreting immune globulin A (IgA) and inflammatory cytokines and stimulating the innate immune system in the intestine.

- Bile is an essential component of cholehepatic and enterohepatic circulation.

- Bile salts are the major organic solutes in bile and function to emulsify dietary fats and facilitate their intestinal absorption.

As the primary function of bile is the facilitation of fat absorption, it plays a vital role in the absorption of fat-soluble vitamins such as vitamins A, D, E, and K. As previously discussed, the bile salts present in bile are bactericidal, thereby destroying most of the pathogenic microorganisms present in the ingested food. Since the pH of the bile is alkaline, bile also plays a vital role in neutralizing excess stomach acid emptied into the duodenum.

Mechanism

The process of bile secretion is driven by two hormones, cholecystokinin (CCK) and secretin. CCK is secreted by the I cells of the small intestine in response to fats and proteins, causing the gallbladder to contract. This contraction causes bile to travel from the cystic duct into the common bile duct. Simultaneously, the sphincter of Oddi relaxes, and bile can enter the lumen of the duodenum. Secretin is secreted by the S cells in the duodenum in response to gastric acid in the duodenal lumen. Secretin stimulates the biliary and pancreatic ductal cells to secrete water and bicarbonate, effectively expanding the volume of bile entering the duodenum.[14]

In the fasting state, the flow of hepatic bile is rerouted toward the gallbladder due to the resistance of the sphincter of Oddi. In the digestive phase, the gallbladder contracts, and the sphincter of Oddi relaxes, allowing bile to be delivered into the duodenum to digest and absorb fats.

Related Testing

Blood tests are extremely useful in identifying and evaluating biliary tract disorders. For example, a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) evaluates serum alanine (AST) and aspartate (ALT) aminotransferases, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin, albumin, and total protein. These values also play an important role in determining a hepatocellular vs. cholestatic pattern of liver disease. For example, a hepatocellular liver injury will show extreme elevations in ALT and AST, while a cholestatic pattern of liver disease will show elevations in serum ALP levels.[15] Fractionalization of alkaline phosphatase enzyme and testing for the enzyme gamma-glutamyl transferase helps assess the site of origin of the enzyme, such as liver versus bone.

Specific Tests Used to Evaluate for Biliary Tract/Gallstone Disease

- Ultrasound:

- A non-invasive test that uses sound waves to examine the bile ducts, liver, and pancreas.

- Imaging can be impaired in obese patients or those who have recently eaten.

- A sonographic Murphy sign is positive when the sonographer pushes directly on the gallbladder with the probe and elicits pain greater than when pushing on other areas of the abdomen.

- Endoscopic ultrasound:

- A scope with an ultrasound probe is passed through the mouth and down into the small intestine, where images of the bile ducts, gallbladder, and pancreas are obtained.

- This test is particularly useful in locating bile duct stones that may easily be missed on regular ultrasound, as well as in diagnosing pancreatic and bile duct cancers.

- Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP):

- An endoscope that can access and assess the bile and pancreatic ducts. In addition, this endoscope has the capability to remove stones from these ducts and can also utilize a sphincter of Oddi manometry to measure the pressure within the sphincter of Oddi muscle.

- Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP):

- A non-invasive test utilizing an MRI machine that creates images of the bile and pancreatic duct, similar to those images obtained by ERCP. The difference between an ERCP and an MRCP is that an MRCP does not require an endoscopy and, therefore, does not have the capability of removing stones or fixing an abnormality seen on the imaging.

- Hepatobiliary Iminodiacetic Acid (HIDA) scan:

- Also known as cholescintigraphy, a HIDA scan is used as a confirmatory test for suspected uncomplicated cholecystitis if previous ultrasound findings are inconclusive. The HIDA scan uses an IV to inject a radioactive tracer into the patient. This tracer undergoes selective uptake by hepatocytes and subsequent excretion into the bile. If the cystic duct is patent, the radiotracer can enter the gallbladder.[16]

Pathophysiology

Anything that decreases the bile secretion or hinders the bile flow causes pathology. Cholestasis can be due to impaired secretion of bile from the hepatocytes (potentially due to some drugs or hormonal imbalance) or any obstruction of the biliary outflow either due to the intrinsic pathology of the biliary tract or external compression of the biliary tract by possibly a mass/tumor of the bile duct and/or pancreas. Biliary tract pathology may cause diseases such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, primary biliary cirrhosis, biliary atresia, etc. The most common reason for bile duct obstruction is gallstones, which eventually cause gallbladder inflammation (acute or chronic cholecystitis). An extensive but non-exhaustive list of biliary tract pathology is listed below.

Biliary Tract Disorders

- Biliary colic:

- Gallstone becomes intermittently lodged in the biliary tree's cystic or common bile duct.[17]

- Acute cholecystitis[18]

- Chronic cholecystitis[19]

- Biliary obstruction:

- Blockage of the bile duct system leads to impaired bile flow from the liver into the intestinal tract.[20]

- Primary biliary cholangitis

- An autoimmune disorder leading to the gradual destruction of intrahepatic bile ducts, resulting in periportal inflammation and cholestasis.[21]

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- A chronically progressive cholestatic liver disorder of unknown etiology characterized by inflammation, fibrosis, and structures of the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic biliary ducts.[22]

- Porcelain gallbladder

- Calcification of the gallbladder wall.[23]

- Biliary tract cholangiocarcinoma

- Rare malignancy of the epithelial cells from various areas of the biliary tree, including intrahepatic, extrahepatic, and perihilar bile ducts.[24]

- Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

- Spasms, strictures, or inappropriate relaxation of the sphincter of Oddi.[25]

- Biliary parasites (e.g., Clonorchis sinensis)[26]

- Gallbladder polyps[27]

- Cholangitis/ascending cholangitis

- Inflammation of the biliary tract system is most commonly caused by an ascending bacterial infection of the biliary tree.[28]

- Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis[29]

- Hyperplastic cholecystoses (adenomyomatosis and cholesterolosis)

- Two conditions characterized by the accumulation of cholesterol within the wall of the gallbladder.[30]

- Choledochal (biliary) cyst[31]

- Cystic dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts, extrahepatic bile ducts, or both.

- Caroli disease (AKA congenital communicating cavernous ectasia of the biliary tree)[32]

- A rare inherited disorder characterized by segmental dilation of the large intrahepatic bile ducts.

- Mirizzi Syndrome[33]

- External compression of the CBD or CHD from impacted gallstones leading to obstruction of these ducts.

- Biliary atresia[34]

- Progressive fibrosing obstructive cholangiopathy of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary system, leading to obstruction of bile flow and neonatal jaundice.

- Choledocholithiasis[35]

- The presence of gallstones within the CBD

- Cholelithiasis[36]

- Cholesterol stones (80%)

- Composed of cholesterol and calcium carbonate

- Pigment stones

- Black pigment stones (10%)

- Composed of calcium bilirubinate

- Associated with hemolytic diseases such as sickle cell anemia, hereditary spherocytosis

- Mixed (Brown pigment) stones (10%)

- Associated with infection

- Arise in inflamed portions of the biliary tract (e.g., due to bacterial or parasitic infections)

- Black pigment stones (10%)

- Cholesterol stones (80%)

Bile Disorders

- Primary bile acid malabsorption (PBAM)[37]

- An idiopathic intestinal disorder associated with congenital diarrhea, steatorrhea, interruption of the enterohepatic circulation, and reduced plasma cholesterol levels.

- Gilbert syndrome[38]

- An autosomal recessive disorder of reduced glucuronidation of bilirubin within the liver, leading to unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and recurrent episodes of jaundice.

- Dubin-Johnson syndrome[39]

- An autosomal recessive disorder of impaired excretion of conjugated from hepatocytes into the bile canaliculi due to a defective multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MPR2).

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome[40]

- An autosomal recessive disorder characterized by a decrease or absence of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase required for glucuronidation of unconjugated bilirubin in the liver, leading to an increase in unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin.

- Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy[41]

- Liver disease of pregnancy appearing in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. It is characterized by pruritus and elevated serum bile acid levels (> 10 mcmol/L).

- Neonatal jaundice[42]

- Elevated total serum bilirubin manifests as yellow discoloration of the skin, sclera, and mucous membranes.

Clinical Significance

The clinical significance of understanding the physiology of the biliary tract is seen in the numerous pathologies associated with bile and the biliary system. Biliary tract disorders can give rise to additional sequelae, including vitamin deficiencies, jaundice, liver cirrhosis, and more. For example, one of the most prevalent causes of vitamin K deficiency deals with the failure of the liver to release bile into the GI tract. This occurs as a result of obstruction of the bile ducts or due to liver disease. This lack of bile will prevent adequate fat digestion and absorption, thereby causing depressed vitamin K absorption.

In addition, a clinically important idea to understand in the physiology of the biliary tract is the four leading causes of gallstones, which include (1) too much absorption of water from bile, (2) too much cholesterol in bile, (3) too much absorption of bile acids from bile, and (4) inflammation of the epithelium of the gallbladder.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Diagram of the Biliary System. Note that the ampulla of Vater is behind the major duodenal papilla—sphincter of Oddi.

Vishnu2011, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Hundt M, Wu CY, Young M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Biliary Ducts. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083810]

Matton APM, de Vries Y, Burlage LC, van Rijn R, Fujiyoshi M, de Meijer VE, de Boer MT, de Kleine RHJ, Verkade HJ, Gouw ASH, Lisman T, Porte RJ. Biliary Bicarbonate, pH, and Glucose Are Suitable Biomarkers of Biliary Viability During Ex Situ Normothermic Machine Perfusion of Human Donor Livers. Transplantation. 2019 Jul:103(7):1405-1413. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002500. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30395120]

Boyer JL. Bile formation and secretion. Comprehensive Physiology. 2013 Jul:3(3):1035-78. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23897680]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEsteller A, Physiology of bile secretion. World journal of gastroenterology. 2008 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 18837079]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBallatori N, Li N, Fang F, Boyer JL, Christian WV, Hammond CL. OST alpha-OST beta: a key membrane transporter of bile acids and conjugated steroids. Frontiers in bioscience (Landmark edition). 2009 Jan 1:14(8):2829-44. doi: 10.2741/3416. Epub 2009 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 19273238]

Sundaram SS, Sokol RJ. The Multiple Facets of ABCB4 (MDR3) Deficiency. Current treatment options in gastroenterology. 2007 Dec:10(6):495-503 [PubMed PMID: 18221610]

Tabibian JH, Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, O'Hara SP, LaRusso NF. Physiology of cholangiocytes. Comprehensive Physiology. 2013 Jan:3(1):541-65. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120019. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23720296]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKalakonda A, Jenkins BA, John S. Physiology, Bilirubin. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261920]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 31196634]

Cowen AE, Campbell CB. Bile salt metabolism. I. The physiology of bile salts. Australian and New Zealand journal of medicine. 1977 Dec:7(6):579-86 [PubMed PMID: 274936]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSannasiddappa TH, Lund PA, Clarke SR. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Unconjugated and Conjugated Bile Salts on Staphylococcus aureus. Frontiers in microbiology. 2017:8():1581. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01581. Epub 2017 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 28878747]

Roskams T, Desmet V. Embryology of extra- and intrahepatic bile ducts, the ductal plate. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2008 Jun:291(6):628-35. doi: 10.1002/ar.20710. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18484608]

Ramesh Babu CS, Sharma M. Biliary tract anatomy and its relationship with venous drainage. Journal of clinical and experimental hepatology. 2014 Feb:4(Suppl 1):S18-26. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2013.05.002. Epub 2013 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 25755590]

Hundt M, Basit H, John S. Physiology, Bile Secretion. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262229]

Iluz-Freundlich D, Zhang M, Uhanova J, Minuk GY. The relative expression of hepatocellular and cholestatic liver enzymes in adult patients with liver disease. Annals of hepatology. 2020 Mar-Apr:19(2):204-208. doi: 10.1016/j.aohep.2019.08.004. Epub 2019 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 31628070]

Snyder E, Kashyap S, Lopez PP. Hepatobiliary Iminodiacetic Acid Scan. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969603]

Sigmon DF, Dayal N, Meseeha M. Biliary Colic. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613523]

Jones MW, Genova R, O'Rourke MC. Acute Cholecystitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083809]

Jones MW, Gnanapandithan K, Panneerselvam D, Ferguson T. Chronic Cholecystitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261986]

Coucke EM, Akbar H, Kahloon A, Lopez PP. Biliary Obstruction. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969520]

Pandit S, Samant H. Primary Biliary Cholangitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083627]

Rawla P, Samant H. Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725866]

Jones MW, Weir CB, Ferguson T. Porcelain Gallbladder. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085521]

Garikipati SC, Roy P. Biliary Tract Cholangiocarcinoma. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32809543]

Crittenden JP, Dattilo JB. Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491794]

Locke V, Kusnik A, Richardson MS. Clonorchis Sinensis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422487]

Jones MW, Deppen JG. Gallbladder Polyp. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262128]

Virgile J, Marathi R. Cholangitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32644372]

Gupta A, Simo K. Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33231978]

Joshi JK, Kirk L. Adenomyomatosis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489201]

Hoilat GJ, John S. Choledochal Cyst. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491694]

Umar J, Kudaravalli P, John S. Caroli Disease. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020679]

Jones MW, Ferguson T. Mirizzi Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29494098]

Vij M, Rela M. Biliary atresia: pathology, etiology and pathogenesis. Future science OA. 2020 Mar 17:6(5):FSO466. doi: 10.2144/fsoa-2019-0153. Epub 2020 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 32518681]

McNicoll CF, Pastorino A, Farooq U, Froehlich MJ, St Hill CR. Choledocholithiasis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722990]

Tanaja J, Lopez RA, Meer JM. Cholelithiasis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262107]

Oelkers P, Kirby LC, Heubi JE, Dawson PA. Primary bile acid malabsorption caused by mutations in the ileal sodium-dependent bile acid transporter gene (SLC10A2). The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997 Apr 15:99(8):1880-7 [PubMed PMID: 9109432]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThoguluva Chandrasekar V, Faust TW, John S. Gilbert Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262099]

Nisa AU, Ahmad Z. Dubin-Johnson syndrome. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons--Pakistan : JCPSP. 2008 Mar:18(3):188-9 [PubMed PMID: 18460254]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBhandari J, Thada PK, Yadav D. Crigler-Najjar Syndrome. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32965842]

Pillarisetty LS, Sharma A. Pregnancy Intrahepatic Cholestasis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31855347]

Ansong-Assoku B, Shah SD, Adnan M, Ankola PA. Neonatal Jaundice. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30422525]