Anatomy, Thorax, Brachiocephalic (Innominate) Veins

Anatomy, Thorax, Brachiocephalic (Innominate) Veins

Introduction

The brachiocephalic veins, also called the innominate veins, are large venous structures located within the thorax and originate from the union of the subclavian vein with the internal jugular vein. The left and right brachiocephalic veins join to form the superior vena cava on the right side of the upper chest. These vessels are a vital component of the human circulatory system, aiding in the drainage of deoxygenated blood from the head and upper limbs.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

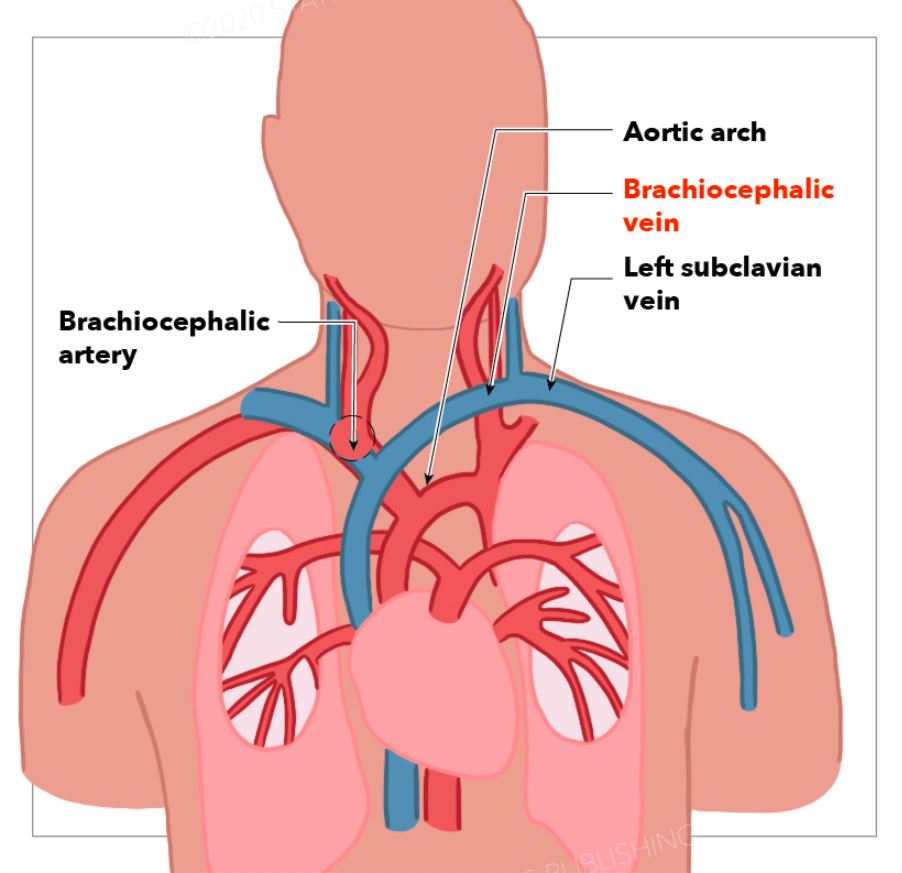

The brachiocephalic veins are formed by the confluence of the subclavian vein and internal jugular vein on the right and left, respectively. The brachiocephalic veins, as well as the vena cava, are valveless vessels. Due to the anatomic position of the superior vena cava on the right of the middle mediastinum, the left brachiocephalic vein is generally longer than the right, allowing for it to bypass the aortic arch (see Image. Brachiocephalic Artery and Vein, Subclavian Vein, and Aortic Arch). The right brachiocephalic vein measures typically 2 to 3 cm, while the left measures approximately 6 cm.

The right vein has relationships with:

- The cartilage of the first rib,

- The infrahyoid muscles (sternothyroid),

- The phrenic nerve and cranial nerve vagus or X

- Parietal pleura

- Brachiocephalic arterial trunk

The left brachiocephalic vein courses inferior from the area of the clavicle at an oblique angle, generally passing anterior to the aortic arch. The left vein has relations with:

- The medial epiphysis of the clavicle

- The infrahyoid muscles (sternothyroid and sternohyoid)

- Retrosternal fat

The primary function of the brachiocephalic veins is to aid in carrying deoxygenated blood from the systemic circulation back to the right side of the heart and eventually to the pulmonary circuit for oxygenation.[1] Blood from the head drains via the internal jugular veins, while blood from the upper extremities drains via the subclavian veins. Other vessels that empty into the brachiocephalic veins include the left and right inferior thyroid veins, left and right internal thoracic veins, and the left superior intercostal vein.[2] The vein consists of several layers:

- An outer layer or adventitia, composed of connective tissue

- The middle layer, or tunica media, is made up of smooth muscle cells

- The tunica intima, or inner layer, with endothelial cells

Embryology

The brachiocephalic veins derive from the cardinal venous system.[3] Three pairs of cardinal veins comprise this system, which begins to drain the embryo's body in the fifth week of life. The right brachiocephalic vein develops from the proximal right anterior cardinal vein, the right common cardinal vein, and the right horn of the sinus venosus. The left anterior cardinal vein leads to the development of the left brachiocephalic vein.[4] The leaflet of embryological derivation is the mesoderm.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Lymphatic vessels within the thorax converge to form bronchomediastinal trunks. The trunks on the right side are typically present on the right brachiocephalic vein, as well as the subserosal surface of the mediastinal pleura. The bronchomediastinal trunks on the left side of the body display more variable courses.[5] The thoracic duct, which is responsible for much of the body’s lymphatic drainage, enters the venous system most often at the junction of the left internal jugular vein and left subclavian vein near the origin of the left brachiocephalic vein.[6] Tributaries to the brachiocephalic veins include the right and left internal mammary veins, pericardiophrenic veins, right and left superior intercostal veins, and the inferior thyroid vein, which terminates into the left brachiocephalic vein.[4]

Nerves

The right phrenic nerve is posterior and lateral to the right brachiocephalic vein. The right vagal nerve courses posteriorly in the thorax, forming the posterior vagal trunk. The left phrenic and vagus nerve runs near the left brachiocephalic vein, with the left vagus nerve forming the anterior vagal trunk.[7]

Muscles

The brachiocephalic veins lie near the muscles of the inferior neck. The confluence of the subclavian and internal jugular veins, which form the brachiocephalic veins, are found on the medial border of the scalenus anterior muscle.[8] The scalene anterior is deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, inserted on the scalene tubercle of the first rib. The subclavian vein passes in front of it to unite with the internal jugular vein; the subclavian artery and brachial plexus pass behind it.

Physiologic Variants

Physiologic anomalies of the brachiocephalic veins are rare, yet research has documented them. The most common variant involves the anomalous veins traversing the space beneath the aortic arch and above the pulmonary artery, crossing in front of the ligament arteriosum or a patent ductus arteriosus if present. Other reported variants include brachiocephalic veins that cross the midline above the aortic arch and/or behind a patent ductus arteriosus. These variations sometimes coexist with other great vessel anomalies, such as a bilateral SVC or a double aortic arch.[1] At least 1 documented case of an absent SVC reports a variant course of the right brachiocephalic vein, which continues posteriorly as the azygos vein before crossing to the left side of the spinal column. The left brachiocephalic vein continues directly posteriorly and inferiorly as the accessory hemiazygos vein and joins the azygos vein at the level of the sixth thoracic vertebra on the left side. In this instance, the venous drainage of the upper body enters the right atrium entirely via the inferior vena cava.[9]

Surgical Considerations

The left brachiocephalic vein may hinder a surgical approach to the aortic arch during cardiac surgical procedures performed via median sternotomy. In such cases, there is reliable documentation that the surgeon may safely divide the left brachiocephalic vein for better access to the aortic arch. There is no proven benefit from the reconstruction of the vein. Long-term anticoagulation following this division has also not been shown to be necessary. The main concern following the division of the left brachiocephalic vein is swelling of the left neck and upper limb, which, if present, generally resolves with conservative management as collateral drainage develops via the azygos/hemiazygos, the internal mammary veins, the lateral thoracic and superficial thoracoabdominal veins, vertebral venous plexus and the transverse sinus.[10]

Another instance that often necessitates consideration of the brachiocephalic veins is the resection of mediastinal tumors. Tumors that invade the SVC, and therefore require resection and reconstruction of the SVC, it has been well documented that temporary bypass may be achieved between the brachiocephalic veins and right atrium, using a small diameter catheter.[11]

Clinical Significance

The brachiocephalic veins are essential central venous access sites and are frequent sites for placing central venous catheters or venous chemotherapy ports. Advances in ultrasound-guided technology have made accessing these structures both feasible and safe.[12] Consideration is necessary for the possibility of vein stenosis following long-term CVC placement. Another rare but documented risk of CVC placement is brachiocephalic vein pseudoaneurysm formation.

Other Issues

Brachiocephalic vein compression may arise as a consequence of mediastinal masses. Although rare, bilateral brachiocephalic vein compression is often clinically indistinguishable from SVC obstruction.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Chen SJ, Liu KL, Chen HY, Chiu IS, Lee WJ, Wu MH, Li YW, Lue HC. Anomalous brachiocephalic vein: CT, embryology, and clinical implications. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2005 Apr:184(4):1235-40 [PubMed PMID: 15788602]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcNeill CJ, Sinnott JD, Howlett D. Bilateral brachiocephalic vein compression: an unusual and rare presentation of multinodular goitre. BMJ case reports. 2016 Oct 8:2016():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-217074. Epub 2016 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 28049119]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDemos TC, Posniak HV, Pierce KL, Olson MC, Muscato M. Venous anomalies of the thorax. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2004 May:182(5):1139-50 [PubMed PMID: 15100109]

Sonavane SK, Milner DM, Singh SP, Abdel Aal AK, Shahir KS, Chaturvedi A. Comprehensive Imaging Review of the Superior Vena Cava. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2015 Nov-Dec:35(7):1873-92. doi: 10.1148/rg.2015150056. Epub 2015 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 26452112]

Murakami G, Sato T, Takiguchi T. Topographical anatomy of the bronchomediastinal lymph vessels: their relationships and formation of the collecting trunks. Archives of histology and cytology. 1990:53 Suppl():219-35 [PubMed PMID: 2252631]

Louzada AC, Lim SJ, Pallazzo JF, Silva VP, de Oliveira RV, Yoshio AM, de Araújo-Neto VJ, Leite AK, Silveira A, Simões C, Brandão LG, Matos LL, Cernea CR. Biometric measurements involving the terminal portion of the thoracic duct on left cervical level IV: an anatomic study. Anatomical science international. 2016 Jun:91(3):274-9. doi: 10.1007/s12565-015-0295-9. Epub 2015 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 26272628]

Irgau I, McNicholas KW. Mediastinal lipoblastoma involving the left innominate vein and the left phrenic nerve. Journal of pediatric surgery. 1998 Oct:33(10):1540-2 [PubMed PMID: 9802809]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDeslauriers J. Anatomy of the neck and cervicothoracic junction. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2007 Nov:17(4):529-47. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2006.12.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18271167]

Madej T, Ghazy T, Ouda A, Knaut M. The venous U-turn: a unique variant of total anomalous superior systemic venous return. European heart journal. 2016 Oct 1:37(37):1520. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw127. Epub 2016 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 27044880]

McPhee A, Shaikhrezai K, Berg G. Is it safe to divide and ligate the left innominate vein in complex cardiothoracic surgeries? Interactive cardiovascular and thoracic surgery. 2013 Sep:17(3):560-3. doi: 10.1093/icvts/ivt244. Epub 2013 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 23736661]

Shimizu N, Tanaka Y, Kuroda S, Nakamura H, Matsumoto G, Mitsui S, Sakai S, Minami K, Kimura K, Okamoto T, Hokka D, Maniwa Y. [Temporary Bypass with 5-Fr Catheter for Reconstruction of Superior Vena Cava]. Kyobu geka. The Japanese journal of thoracic surgery. 2018 Dec:71(13):1077-1080 [PubMed PMID: 30587745]

Sun X, Xu J, Xia R, Wang C, Yu Z, Zhang J, Bai X, Jin Y. Efficacy and safety of ultrasound-guided totally implantable venous access ports via the right innominate vein in adult patients with cancer: Single-centre experience and protocol. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2019 Feb:45(2):275-278. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.07.048. Epub 2018 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 30087070]