Introduction

The ability to perform a thorough and accurate breast exam is an important skill for medical practitioners of many levels and specialties. A clinical breast exam is a key step in the diagnosis and surveillance of a number of benign and malignant breast diseases. When used as part of a multimodal evaluation, the breast exam provides important information used in both the workup and management of many diseases of the breast. Current recommendations for breast cancer screening intervals and tests vary; however, many guidelines agree that a clinical breast exam is warranted for women with abnormal findings on mammography and as part of annual screening for certain groups of women at increased risk for breast cancer.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Knowledge of the basic anatomy and physiology of the breast provides a framework for understanding the pathophysiology of breast disease. Many diseases of the breast arise from a derangement of normal function and follow along a spectrum of mild, benign abnormality to a malignant process.

Embryology and Physiology

The breasts originate from ventral buds of ectoderm in the fifth to sixth week of fetal development. These buds are bilateral ridges that extend from the future sites of the axilla to the inguinal region, the so-called "milk line," along which accessory nipples and breast tissue may occasionally be found in the adult. Two buds of ectoderm penetrate the mesenchyme along the ventral ridges overlying the pectoral tissue, which are referred to as primary buds. These subsequently proliferate into 15 to 20 secondary buds, which later develop into the lobes found in the adult breast. Supportive connective tissue derives from epithelial cells. Breasts develop similarly between males and females in utero and are identical until the onset of puberty. During puberty, various hormonal signals initiate further maturation of the female breast, most notably inducing ductal and connective tissue proliferation through the effects of estrogen and progesterone[2]. Complete breast maturity is not reached until pregnancy and delivery, during which time the epithelial tissue proliferates, and milk production is initiated. Lactation occurs as long as there is neural stimulation of the nipple areolar complex through nursing. Once this ceases, the buildup of pressure of unexpressed milk in the ductal system results in epithelial atrophy. During menopause, decreases in circulating estrogen and progesterone cause the lobular tissue to undergo involution[3]. At this time, connective tissue becomes more dense and adipose tissue gradually replaces breast parenchyma.

Clinical Anatomy

The adult breast is roughly conical, the base of which overlies the pectoralis muscles in the upper portion of the chest[4]. The physical boundaries of the breast are the clavicle superiorly, the sternum medially, the insertion of the rectus abdominis muscles inferiorly, and the serratus anterior muscles laterally. The posterior breast tissue lies on the pectoralis major fascia. The breast contains 15 to 20 lobes which are further divided into smaller functional lobules. Cooper's ligaments are connective tissue that attach perpendicularly to the dermis that help to support the breast. The breast is divided into quadrants or described in comparison to a clock face for ease of communication of any findings. The upper outer quadrant of the breast contains a greater volume of tissue than elsewhere, and this is also the most common location for a breast malignancy to arise. The upper outer quadrant extends superior-laterally toward the axilla and shoulder. This portion of the breast is called the axillary tail of Spence.

Common Physiologic Changes

The breast undergoes many changes throughout a woman's life and a typical menstrual cycle, and these are important to keep in mind when performing a breast exam. During pregnancy and lactation, hypertrophy of the lactiferous ducts occurs with engorgement of ducts and alveoli with breast milk. In a non-pregnant female, in the late luteal phase before menses, fluid accumulation in the breast occurs in the form of intralobular edema which may cause discomfort. Fibrocystic changes may become exacerbated and resolve over the course of a menstrual cycle. After menopause, the breast undergoes involution, with the replacement of the pre-existing breast parenchyma with adipose and connective tissue.

Indications

Complaints of breast pain, skin changes, nipple discharge, lumps, gross changes in size or shape, or any other feature that cause concern to the patient warrant a clinical breast exam[5]. While there is currently controversy regarding the recommendation for women to perform self-breast exams for breast cancer screening[6][7][8][9], the medical practitioner nonetheless must evaluate a patient who presents with changes noticed during a self-breast exam (see Image. Breast Self-Examination). Many breast cancers are in fact discovered by patients themselves during intentional or incidental self-breast exam. Additionally, abnormal findings on screening, surveillance, or incidental breast imaging (mammogram, ultrasound, MRI, chest CT, and PET) that are identified as suspicious by the interpreting radiologist should be further evaluated through clinical breast exam[10].

Guidelines

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network screening guidelines suggest that women between 25 and 40 years old who are asymptomatic and have no special risk factors for breast cancer undergo a clinical breast exam every 1 to 3 years. Women older than age 40, women with increased risk factors for breast cancer, history of breast cancer, and/or symptomatic patients are recommended to receive more frequent clinical breast exams[9].

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that any screening regimen should involve a discussion of potential risks of screening with the patient. With this in mind, the group recommends offering a clinical breast exam for average-risk women aged 25 to 39 every 1-3 years, and an annual breast exam to women aged over 40 years[6].

The American Cancer Society does not recommend regular clinical breast exams for cancer screening for women in any risk group. It does state, however, that all women should pay attention to the typical appearance and texture of their breasts and report any changes to their doctor right away[11].

The United States Preventive Services Task Force does not currently provide recommendations for the use of clinical breast exams in breast cancer screening, citing a lack of complete evidence based on available studies[1]. However they do recommend obtaining an extended medical history for increased genetic susceptibility to breast cancer. These historical risk features include a personal history of breast cancer prior to age 50, a personal history of bilateral breast cancer, a family history of an individual with breast and ovarian cancer, a family history of at least 1 male member with breast cancer, multiple family members with breast cancer and Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. Any of these historical issues noted on initial and followup screening assessment should be further evaluated with genetic counseling. (PMID 24366376)

Contraindications

Contraindications include lack of patient cooperation or consent. Patient anxiety may occasionally prevent an exam, but this may be minimized with calm assurance and working with the patient to optimize comfort[4].

Preparation

Policies vary by institution, but it is often advisable to ask a same-sex chaperone to accompany the examiner into the patient's room for the patient's comfort and protection. Adopting a courteous and gentle approach toward the patient is encouraged, as patients may feel some degree of anxiety during the exam. It is important to have the patient change into a hospital gown before the exam to facilitate exposure of the entire breast anatomy. A sheet should be available to cover the patient's lower half for comfort. During the exam, a sheet or the hospital gown should be used to cover the contralateral breast[4].

Technique or Treatment

Practitioners use many techniques with success, and each examiner will likely develop his or her preferences. Regardless of which approach is utilized, it is important always to follow a consistent pattern to minimize the likelihood that anything is missed.[11][10][4]

Inspection

The breasts are first visually inspected with the patient in a seated position facing the examiner. The patient is instructed to place their hands on their hips as well as raise them above their head. This allows the examiner to assess the breasts in many positions and observe overall size, shape, symmetry, nipple size, shape, texture, and color. Variations in any of these should be noted concerning previous exams as well as in comparison to the contralateral breast. Areas of skin thickening, dimpling, or fixation relative to the underlying breast tissue should also be noted on visual inspection. These can be exaggerated during movement as well as by asking the patient to flex the pectoral muscles with hands on hips.

Palpation

After completing the visual inspection, the patient should be instructed to lay supine. If a side-specific breast complaint is being evaluated, the examiner should begin his/her exam on the opposite, or "normal" side. As one breast is examined, the other is covered for the patient's comfort. The patient should place the ipsilateral hand above and/or behind their head to flatten the breast tissue as much as possible. The breast tissue itself is evaluated using a sequence of palpation that allows serial progression from superficial to deeper tissues. This is best accomplished utilizing the examiner's finger pads, usually with the hand in a slightly cupped position. A variety of techniques exist, but the most often used are the radial "wagon wheel" or "spoke" method, the vertical strip method, and the concentric circle's method. As stated previously, it is important that the examiner chooses a method and is consistent from exam to exam. The overall consistency of the breast is documented (soft, firm, nodular). Any masses or tender lesions are noted concerning their location in a conventional quadrant or clock face configuration. When documenting findings, characteristics of any abnormalities should be included, such as size, shape, texture, mobility, delimitation, tenderness, and approximate depth. Attention is then turned to the nipple areolar complex, where these tissues themselves are palpated for abnormalities. Also, the examiner should assess for expressable nipple discharge by placing both hands on the breast on either side of the areola and gently but firmly pressing down into the breast tissue.

Following a complete exam of the breast, the axilla and supraclavicular area should be palpated for lymphadenopathy. Lymph node abnormalities may present in a variety of forms, but most often any palpable nodes of concern will be slightly enlarged and have a somewhat firmer texture than the typical soft, rubbery one. As with any masses, approximate document number, size, texture, mobility, and delimitation of any palpable lymph nodes. Occasionally, the entire axilla will feel "full," without defined lymphadenopathy. This may relate to the patient's normal anatomy or indicate the presence of diffusely matted lymph nodes.

A breast exam in a male is often somewhat simpler due to a smaller volume of tissue to assess unless the patient is extremely obese or gynecomastia is present. The same principles apply to examining the male breast.

Documentation

Common terminology found in the documentation of a breast exam includes the following:

- Symmetrical or asymmetrical

- Shape (ptotic, pendulous, any scars or deformities with descriptions)

- Texture (soft, nodular, fibrocystic, dense, presence of inframammary ridge in large breasts)

- Masses (described as indicated above versus no masses evident)

- Nipple-areolar complex (pink, brown, everted, inverted, discharge present/absent with description, presence of dry, scaly texture concerning for Paget's disease)

- Skin (warm, dry, presence/absence of erythema, edema, peau d'orange appearance, open sores, draining fluid collections)

Clinical Significance

The findings of the breast exam are important in guiding future clinical care related to the specific complaint. For example, a lesion identified on imaging that cannot be palpated may need to be biopsied under image guidance[5]. For cellulitis or breast abscess, clinical observation of the breast will be crucial to determining if the infection is responding to therapy. Presence or absence of palpably enlarged lymph nodes at the initiation of treatment for malignancy will dictate next steps in both surgical and oncological management.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Breast exams may be performed by many clinicians including nurses. However, it is important to understand that current guidelines do not recommen regular clinical breast exams for cancer screening for women in any risk group. However, the women should be educated on the importance of changes to to the typical appearance and texture of their breasts and report any changes to their doctor right away[11].

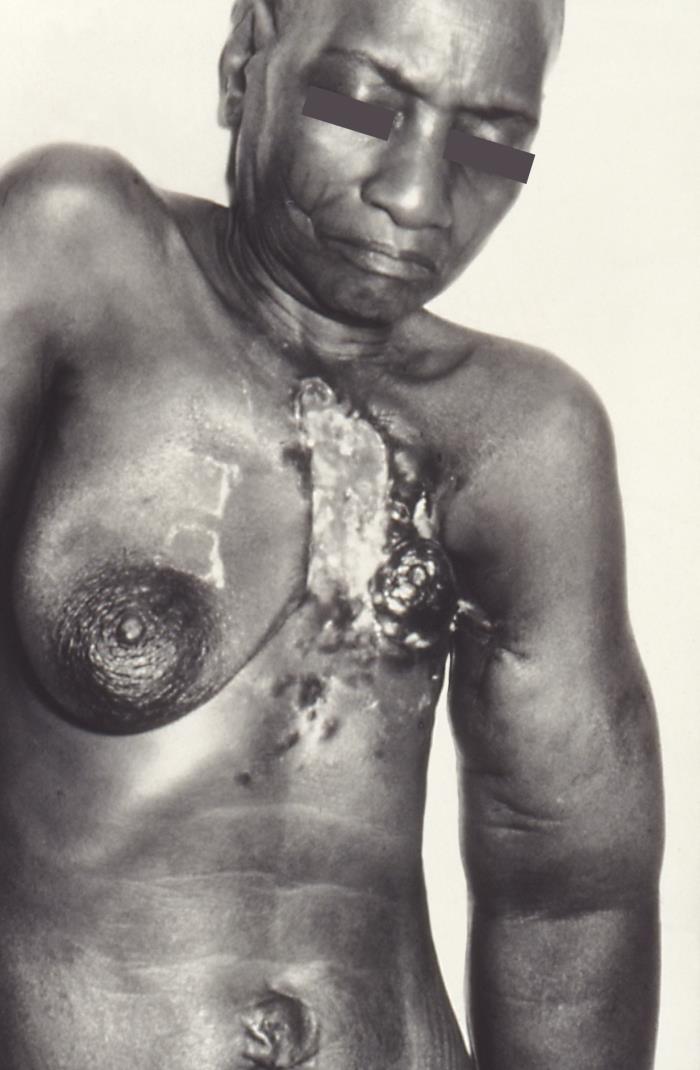

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Siu AL, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2016 Feb 16:164(4):279-96. doi: 10.7326/M15-2886. Epub 2016 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 26757170]

Hens JR, Wysolmerski JJ. Key stages of mammary gland development: molecular mechanisms involved in the formation of the embryonic mammary gland. Breast cancer research : BCR. 2005:7(5):220-4 [PubMed PMID: 16168142]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFendrick JL, Raafat AM, Haslam SZ. Mammary gland growth and development from the postnatal period to postmenopause: ovarian steroid receptor ontogeny and regulation in the mouse. Journal of mammary gland biology and neoplasia. 1998 Jan:3(1):7-22 [PubMed PMID: 10819501]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDugoff L, Pradhan A, Casey P, Dalrymple JL, Abbott JF, Buery-Joyner SD, Chuang A, Cullimore AJ, Forstein DA, Hampton BS, Kaczmarczyk JM, Katz NT, Nuthalapaty FS, Page-Ramsey SM, Wolf A, Hueppchen NA. Pelvic and breast examination skills curricula in United States medical schools: a survey of obstetrics and gynecology clerkship directors. BMC medical education. 2016 Dec 16:16(1):314 [PubMed PMID: 27986086]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWeiss JE, Goodrich M, Harris KA, Chicoine RE, Synnestvedt MB, Pyle SJ, Chen JS, Herschorn SD, Beaber EF, Haas JS, Tosteson AN, Onega T, PROSPR (Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens) consortium. Challenges With Identifying Indication for Examination in Breast Imaging as a Key Clinical Attribute in Practice, Research, and Policy. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2017 Feb:14(2):198-207.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.08.017. Epub 2016 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 27744009]

Anderson BL, Urban RR, Pearlman M, Schulkin J. Obstetrician-gynecologists' knowledge and opinions about the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) committee, the Women's Health Amendment, and the Affordable Care Act: national study after the release of the USPSTF 2009 Breast Cancer Screening Recommendation Statement. Preventive medicine. 2014 Feb:59():79-82. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.11.008. Epub 2013 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 24246966]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUS Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Annals of internal medicine. 2009 Nov 17:151(10):716-26, W-236. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19920272]

Cheng TM, Freund KM, Winter M, Orlander JD. Limited adoption of current guidelines for clinical breast examination by primary care physician educators. Journal of women's health (2002). 2015 Jan:24(1):11-6; quiz 16-7. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4772. Epub 2014 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 25405388]

Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, Calhoun KE, Daly MB, Farrar WB, Garber JE, Gray R, Greenberg CC, Greenup R, Hansen NM, Harris RE, Heerdt AS, Helsten T, Hodgkiss L, Hoyt TL, Huff JG, Jacobs L, Lehman CD, Monsees B, Niell BL, Parker CC, Pearlman M, Philpotts L, Shepardson LB, Smith ML, Stein M, Tumyan L, Williams C, Bergman MA, Kumar R. Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis, Version 3.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2018 Nov:16(11):1362-1389. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0083. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30442736]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBeitler AL, Hurd TC, Edge SB. The evaluation of palpable breast masses: common pitfalls and management guidelines. Surgical oncology. 1997 Dec:6(4):227-34 [PubMed PMID: 9775409]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRusso J, Russo IH. Toward a physiological approach to breast cancer prevention. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 1994 Jun:3(4):353-64 [PubMed PMID: 8061586]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence