Introduction

Brugada syndrome is a genetic disease that predisposes patients to fatal cardiac arrhythmias. It is named after Josep and Pedro Brugada who first described it in 1992. The syndrome is characterized by the ECG findings of a right bundle branch block and ST-segment elevations in the right precordial leads (V1-V3). [1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The first genetic association with Brugada syndrome discovered was a loss-of-function mutation in the cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel gene SCN5A. It is thought to be found in 15-30% of Brugada Syndrome cases. [2] Mutations in calcium and potassium channels, associated channel proteins, and desmosomal proteins have also been linked with the disease. Brugada syndrome is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern; however, affected individuals may demonstrate variable expressivity and reduced penetrance. Additionally, many environmental and genetic factors may influence the phenotype, including temperature, medications, electrolyte abnormalities, and cocaine.[3]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of Brugada Syndrome is approximately 3 to 5 per 10,000 people. Brugada syndrome is approximately 8 to 10 times more common in males than females. This gender difference, however, is not found in pediatric patients. This has been hypothesized to be due to higher testosterone levels after puberty and different proportions of ionic currents based on sex. Brugada syndrome is also more prevalent in those who are of Southeast Asian descent. The mean affected age is 41 years old. Brugada syndrome accounts for 4% of all sudden cardiac deaths. [3]

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism for Brugada Syndrome is not clear. There are two main physiologic hypotheses that have been suggested: the repolarization disorder and the depolarization disorder models. According to the repolarization disorder model, the decrease in sodium current secondary to the loss-of-function sodium channel mutation causes the right ventricular epicardium's action potential to have a deeper notch when compared to the action potential of the endocardium. This difference in current can lead to the typical EKG finding of Brugada syndrome and subsequent fatal arrhythmias. The depolarization disorder model, on the other hand, suggests that the EKG findings of Brugada syndrome are secondary to a delay in depolarization due to slow conduction in the right ventricular outflow tract.

Histopathology

When Brugada syndrome was first described, it was thought to be only in structurally normal hearts. However, newer research revealed right ventricular outflow tract abnormalities, such as an increase in adipose tissue and fibrosis. These structural abnormalities support the depolarization disorder model as a possible cause of slower conduction in the right ventricular outflow tract. Nonetheless, whether these structural abnormalities account for the arrhythmias caused in Brugada syndrome or that they are the result of the disease and aging process is still a matter of debate. [4]

History and Physical

Symptoms of Brugada syndrome range from the absence of any symptoms to sudden cardiac death. Sudden cardiac death typically occurs during sleep, possibly secondary to increased vagal tone. Approximately 80% of Brugada syndrome patients who develop ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation experience syncope. Palpitations and dizziness have also been described as possible symptoms. History of a febrile illness may be present as fever may precipitate symptoms and arrhythmias. 10 to 30% of Brugada syndrome patients will have an atrial arrhythmia, and supraventricular tachycardia is also more common in Brugada syndrome patients than the general population. However, 72% of those with Brugada syndrome will not show any symptoms, and 28% will not have a family history of sudden cardiac death.

Evaluation

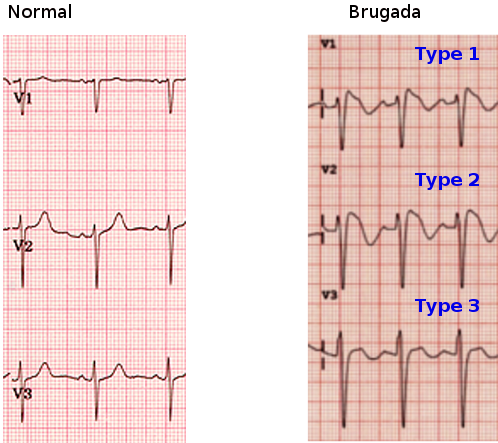

A 12-lead electrocardiogram is significant to both diagnose and decide management options of Brugada syndrome. Three different ECG patterns have been described in Brugada syndrome patients: coved ST elevations greater than 2 mm accompanied with an inverted T wave (type I), saddleback-shaped ST elevation greater than 2 mm (type II), and saddle-back shaped ST elevations less than 2 mm (type III). Additionally, patients with a normal ECG and high-risk factors may require a drug challenge test to reveal the typical ECG findings of ST elevations in the precordial leads V1 to V3. These high-risk factors that may require provocative drug testings include having a family history of Brugada syndrome, family history of sudden cardiac death, and symptoms consistent with Brugada syndrome in the setting of questionable ECG abnormalities. [3]

Class IA antiarrhythmics (such as procainamide and ajmaline) and IC antiarrhythmics (such as flecainide and propafenone), which act as sodium channel blockers, are the drugs used in the challenge test. Brugada ECG findings may also be revealed after cocaine use or tricyclic antidepressant toxicity. Electrolyte abnormalities, such as hyperkalemia and hypercalcemia have been known to reveal ST elevations in the right precordial leads.[5]

If a drug challenge test is normal in a pediatric patient, it may require repetition after the child reaches puberty, given the hormonal effects on Brugada syndrome phenotype. Another diagnostic test described to expose the ST elevations of Brugada syndrome is the full stomach test, where ECGs are obtained before and after a large meal, which causes an increase in vagal tone. Other tests that may be useful for some patients include genetic testing for SCN5A mutations and invasive electrophysiology. [3]

Treatment / Management

An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is the mainstay of treatment of Brugada syndrome patients. Current recommendations are to perform ICD placement in those who survived cardiac arrest, patients with Brugada ECG abnormalities and syncope, and those who can have Brugada ECG findings on drug challenge tests. Pharmacological treatment with quinidine is also an option. There are conflicting results about using quinidine instead of ICD placement; however, quinidine is useful in Brugada syndrome patients with an ICD who experience multiple shocks and in those who have contraindications for ICD placement. Finally, radio frequency ablation of the anterior part of the right ventricular outflow tract is a new, emerging therapy with a promising prognosis for Brugada syndrome patients. Treatment of asymptomatic individuals with Brugada syndrome ECG findings is more complicated. Personalized risk-stratification is essential in providing the right management for these asymptomatic patients depending on their risk factors using a multi-disciplinary approach and with close and frequent follow-up. [6]

Differential Diagnosis

Many of the conditions that may be mistaken for Brugada syndrome also cause syncope as a common symptom. Standard of care for evaluation of syncope is to obtain a 12-lead ECG to evaluate for many of such diseases that may resemble Brugada syndrome. These diseases include QT prolongation, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, pulmonary embolism, sick sinus syndrome, early repolarization syndrome, electrolyte abnormalities, and atrial fibrillation. [3]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Brugada syndrome is not very common, but because it is associated with sudden death, it is important for healthcare workers to be aware of the ECG presentation. The disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a cardiologist, electrophysiologist and a genetic counselor. The key to diagnosis is a comprehensive medical history of syncopal attacks, chest discomfort or dizziness. Once the diagnosis is made, patients need to be educated about the potential for cardiac arrest. While an ICD is routinely implanted in these patients, it also predisposes them to device-related complications and inappropriate shocks. The actual incidence of death from Brugada syndrome is not known but may account for 3-20% of all sudden deaths in patients with structurally normal hearts. Sudden deaths tend to occur early after the fourth decade of life. The patient, family, and coworkers must be educated about the basics of CPR. Once the diagnosis of Brugada syndrome is made, genetic counseling should be offered to the family.[7][8] (Level V)

Media

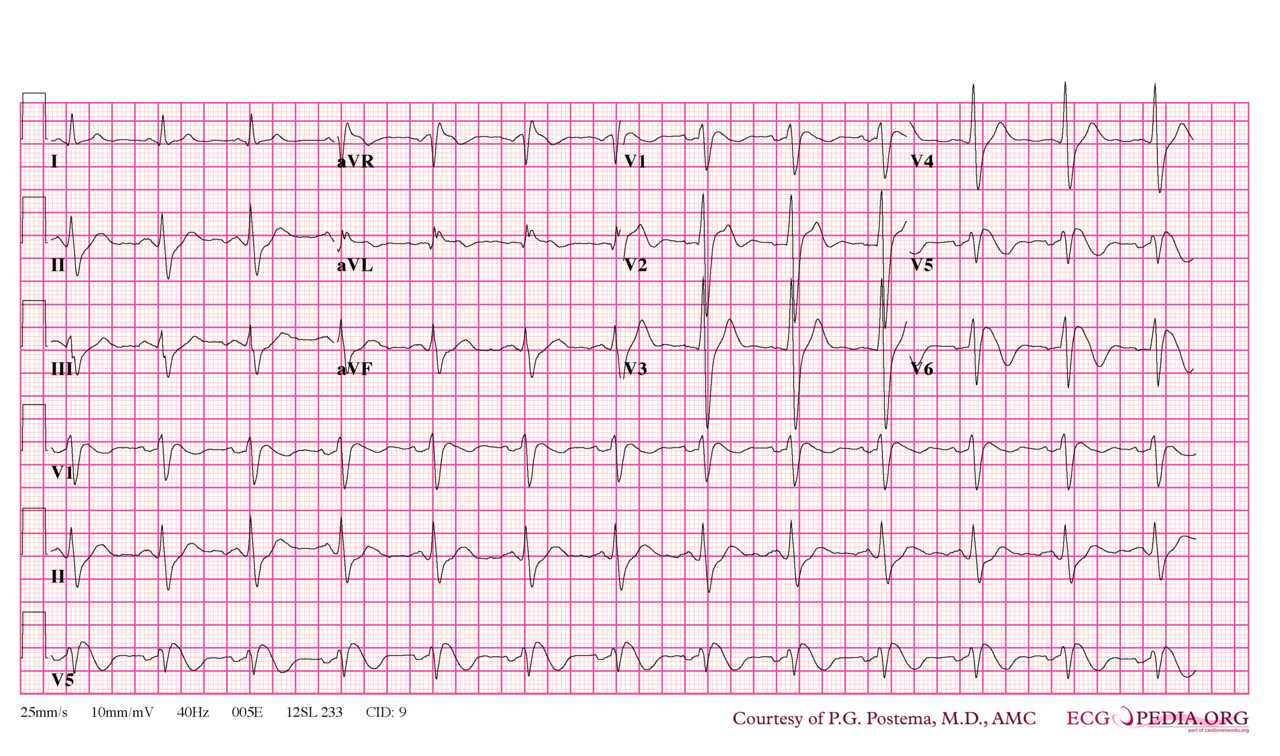

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Brugada syndrome type 1. Note that V5 is placed one intercostal space above V1 (V1 IC4) and V6 is placed one intercostal space above V2 (V2 IC3). Type I morphology is seen in V1, V1 IC3 and V2 IC3. Furthermore, there is a horizontal QRS axis, broad P waves, wide S waves in the lateral and inferior leads and fractionation of the QRS complex in III and aVL. Contributed by P.G. Postema, M.D., AMC

References

Brugada P, Brugada J. Right bundle branch block, persistent ST segment elevation and sudden cardiac death: a distinct clinical and electrocardiographic syndrome. A multicenter report. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1992 Nov 15:20(6):1391-6 [PubMed PMID: 1309182]

Kapplinger JD, Tester DJ, Alders M, Benito B, Berthet M, Brugada J, Brugada P, Fressart V, Guerchicoff A, Harris-Kerr C, Kamakura S, Kyndt F, Koopmann TT, Miyamoto Y, Pfeiffer R, Pollevick GD, Probst V, Zumhagen S, Vatta M, Towbin JA, Shimizu W, Schulze-Bahr E, Antzelevitch C, Salisbury BA, Guicheney P, Wilde AA, Brugada R, Schott JJ, Ackerman MJ. An international compendium of mutations in the SCN5A-encoded cardiac sodium channel in patients referred for Brugada syndrome genetic testing. Heart rhythm. 2010 Jan:7(1):33-46. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.09.069. Epub 2009 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 20129283]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSarquella-Brugada G, Campuzano O, Arbelo E, Brugada J, Brugada R. Brugada syndrome: clinical and genetic findings. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2016 Jan:18(1):3-12. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.35. Epub 2015 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 25905440]

Meregalli PG,Wilde AA,Tan HL, Pathophysiological mechanisms of Brugada syndrome: depolarization disorder, repolarization disorder, or more? Cardiovascular research. 2005 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 15913579]

Littmann L, Monroe MH, Kerns WP 2nd, Svenson RH, Gallagher JJ. Brugada syndrome and "Brugada sign": clinical spectrum with a guide for the clinician. American heart journal. 2003 May:145(5):768-78 [PubMed PMID: 12766732]

Sieira J, Dendramis G, Brugada P. Pathogenesis and management of Brugada syndrome. Nature reviews. Cardiology. 2016 Dec:13(12):744-756. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.143. Epub 2016 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 27629507]

Louis C, Calamaro E, Vinocur JM. Hereditary arrhythmias and cardiomyopathies: decision-making about genetic testing. Current opinion in cardiology. 2018 Jan:33(1):78-86. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000477. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29059074]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMizusawa Y, Recent advances in genetic testing and counseling for inherited arrhythmias. Journal of arrhythmia. 2016 Oct [PubMed PMID: 27761163]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence