Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Calcaneus

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Calcaneus

Introduction

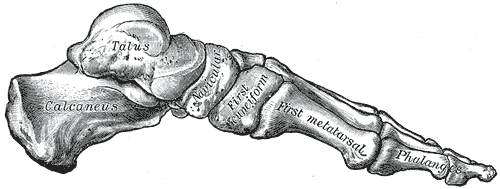

Often called heel, the calcaneus is a large and strong bone that forms the back of the foot and transfers most of the body weight from the lower extremity to the ground. It is the largest of the seven articulating bones that make up the tarsus. The calcaneus is located in the hindfoot with the talus and articulates with the talus and cuboid bones. Numerous ligaments and muscles attach to the calcaneus and help with its role in human bipedal biomechanics.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The calcaneus is a roughly rectangular prism-shaped bone located inferior to the talus and posterior to the midfoot. The long axis of the prism extends approximately along the mid-line of the foot. To understand the calcaneus structure, it is necessary to examine its six surfaces separately.

The posterior surface of the calcaneus has a circular convex structure with three distinct facets. The middle facet serves as the attachment site for the calcaneal tendon (Achilles tendon), while the superior facet is separated from the calcaneal tendon by the retrocalcaneal bursa. The inferior facet bends towards the lower calcaneal surface to form the calcaneal tuberosity, the lowest part of the posterior calcaneal surface. The lower calcaneal surface or plantar surface forms from the forward protrusion of the calcaneal tuberosity, which leads to the formation of medial and lateral processes on both sides, and the calcaneal tubercle in the front.

The lateral calcaneal surface is a wide, flat surface, except for the two bony protrusions on it. The protrusion in the front is the peroneal tubercle (fibular trochlea) above and below which the tendons of the fibularis brevis and fibularis longus muscles pass, respectively. The protrusion in the back is a small bony elevation that gives attachment to the calcaneofibular ligament. The medial calcaneal surface is home to a bone protrusion, called sustentaculum tali, which carries the middle talar articular facet (one of the three talocalcaneal joint facets). And in the inferior aspect of the sustentaculum tali, there exists a groove that houses the flexor hallucis longus tendon.

The superior calcaneal surface hosts the anterior and posterior talar articular facets. The groove between these two facets so-called the calcaneal sulcus, and the corresponding talar sulcus join together to form the tarsal sinus (sinus tarsi). The tarsal sinus is a quite large space located between the anterior portions of the calcaneus and talus, and it contains several neurovascular structures and ligaments, some portions of the subtalar joint capsule, and fat. The anterior calcaneal surface is the smallest face that has an articular facet for the calcaneocuboid joint.

The calcaneus articulates with talus through the talocalcaneal joint in which the contact between the two bones derives from the anterior, middle, and posterior facets. The talocalcaneal joint, also known as the subtalar joint, allows for essential foot motions such as inversion, eversion, dorsiflexion, and plantarflexion of the foot. Besides, the calcaneus serves as an attachment point for the Achilles tendon, which produces aids in plantar flexion of the foot vital for standing, walking, running, and jumping. The calcaneus serves as an attachment point also for muscles that move the toes. The bone has several joint stabilizing ligaments attached to it, such as the calcaneofibular, talocalcaneal, calcaneocuboid, and calcaneonavicular ligaments. The plantar aponeurosis and long plantar ligament support the arch of the foot and attach to the calcaneus as well.[1][2]

Embryology

The tarsal bones form by endochondral ossification and become recognizable on the 43rd day of the intrauterine life. The calcaneus, of which the ossification center begins to develop by the fourth week, becomes visible as a separate structure under the talus on the 55th day. Later on, the subtalar joint and sinus tarsi become recognizable by the third and fourth months, respectively.[3][4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The calcaneus is surrounded by and receives its blood supply from a superficial network of arteries called the calcaneal anastomosis, which is formed by branches of the posterior tibial and fibular arteries. Much of the lymphatic flow follows the vasculature and flows up the leg through the popliteal and inguinal lymph nodes before passing through the thoracic duct.[1][2]

Nerves

The calcaneus receives its nerve supply from branches of the tibial and sural nerves. The calcaneal nerve branches include the medial calcaneal branches of the tibial nerve and lateral calcaneal branches of the sural nerve.[1][2]

Muscles

Three muscles join together to form the Achilles tendon and connect to the calcaneal tubercle. Additionally, six muscles originate from the calcaneal surface and disperse to the areas where they function.

The gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris: They are the primary plantar flexors that combine to form the Achilles tendon. The Achilles tendon attaches to the calcaneal tubercle.

The extensor digitorum brevis: It originates on the dorsolateral side of the calcaneus and provides extension of the second to fourth digits.

The abductor hallucis: It originates on the medial process of calcaneal tuberosity and abducts the first digit.

The extensor hallucis brevis: It originates on the dorsal aspect of the calcaneus and extends the first digit.

The abductor digiti minimi: It originates on the calcaneal tubercle and provides flexion and extension of the fifth toe.

The flexor digitorum brevis: It originates on the calcaneal tubercle and helps provide flexion to the second to fourth digits.

The quadratus plantae: It originates on the lateral and medial processes of the calcaneus and helps provide flexion at the distal interphalangeal joint.[1][2]

Physiologic Variants

Physiologic variants of the calcaneus include pseudofracture of the apophysis, nutrient foramen, pseudocyst, transient plantar bone spur, os sustentaculi, and os calcaneus secundarius. Pseudofracture of the apophysis is the term used for the fragmented appearance of a normally partially ossified calcaneal apophysis that mimics a fracture. A nutrient foramen that transmits blood vessels may sometimes be observed on the calcaneal plantar surface on foot radiography and misdiagnosed as a true lesion. A pseudocyst is a triangular ill-defined rarefaction area due to the deficiency of the normal spongy bone seen in the middle part of the calcaneus on the lateral foot radiograph. Transient plantar bone spurs are small spurs of the plantar calcaneal surfaces of infants. They are usually bilateral and symmetrical and disappear until the age of 1.[5] Os sustentaculi is a very rare accessory ossicle attached to the back of the sustentaculum tali by a fibrocartilaginous synchondrosis. And os calcaneus secundarius is another rare accessory ossicle located in the space between the calcaneus, cuboid, talus, and navicular.[6]

Surgical Considerations

Haglund deformity is a bony exostosis that extends from the posterior superior calcaneus where the Achilles tendon attaches. The etiology of the condition is unknown. It most commonly presents in middle-aged individuals with bilateral pain, erythema, and other signs of inflammation. Treatment is usually conservative and involves non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Achilles stretching, heel lifts, appropriate footwear, and orthotics. Bone exostosis can be surgically excised in Haglund deformity cases where conservative therapy has failed.[7][8]

Plantar fasciitis is a very prevalent disorder characterized by a non-inflammatory structural breakdown of the connective tissue that makes up the plantar aponeurosis or fascia of the foot. It mostly occurs as the result of the overuse in runners and presents with unilateral sharp pain and discomfort along the plantar surface of the foot. Treatment is primarily conservative with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, rest, stretching, physical therapy, steroid injections, and many other non-surgical approaches. The cases where conservative treatment is unsuccessful can have treated with surgical plantar fasciotomy. Besides, minimally invasive endoscopic approaches, which reportedly have yielded good results, have been introduced in the last decade.[9][10]

Fractures of the calcaneus are relatively common and usually occur due to a fall from a height or a motor vehicle accident. Treatment depends on the extent and type of fracture. The Sanders classification system often allows the categorization of intraarticular fractures of the calcaneus into four types with the types II, III, and IV, usually requiring surgery. Fractures that are open, significantly displaced or comminuted also require surgical fixation. Regardless of the treatment, almost all calcaneal fractures initially receive treatment with a non-weight bearing status.[11][12][13]

Clinical Significance

Many types of pathologies, such as congenital, infectious, traumatic, neoplastic, and inflammatory, can affect calcaneus. Among these, the disorders that have priority in terms of frequency are briefly summarized below.

Congenital disorders: The most important congenital disorder of calcaneus is the tarsal coalition. The tarsal coalition refers to the full or partial union between at least two bones of the midfoot and hindfoot. The most commonly encountered types are the calcaneonavicular and talocalcaneal coalitions. Although rare, calcaneocuboid coalition also is among the types of tarsal coalition.[14]

Infectious disorders: Calcaneal infections can occur as a result of various etiologies such as trauma, chronic pressure exposure, and postoperative wound-healing complications. Patients with diabetes are particularly prone to the development of osteomyelitis in their feet, and calcaneus is frequently affected in these cases.[15]

Traumatic disorders: The calcaneus fracture, which constitutes 60% of all tarsal fractures, is the most commonly encountered bone fracture of the tarsus. It is most often detected in the third decade of life, and the falls from a height and motor vehicle accidents are the major injury mechanisms.[11][12][13]

Neoplastic disorders: Approximately 3% of all osseous tumors occur in the foot and ankle. Solitary bone cysts, intraosseous lipoma, osteoid osteoma, chondroblastoma, chondrosarcoma, and Ewing sarcoma are among the lesions that tend to the calcaneus.[16]

Inflammatory disorders: Bone erosions caused by retrocalcaneal bursitis and/or spontaneous rupture of the inflamed Achilles tendon are detectable at the posterior aspect of the calcaneus in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. And in cases of seronegative arthritis, bone erosions at the attachment site of the plantar aponeurosis along the plantar surface of the calcaneus may occur. Tophi in the adjacent soft tissues may cause pressure bone erosions at the calcanei of patients with gout (5). Sever's disease or calcaneal apophysitis is another inflammatory disorder that is characterized by the inflammation of the growth plate of the heels of growing children.[17]

Media

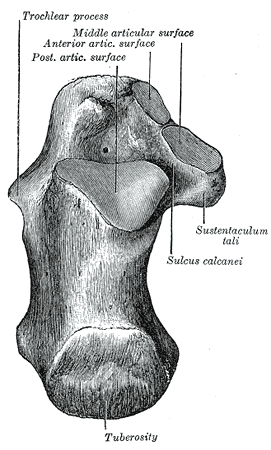

(Click Image to Enlarge)

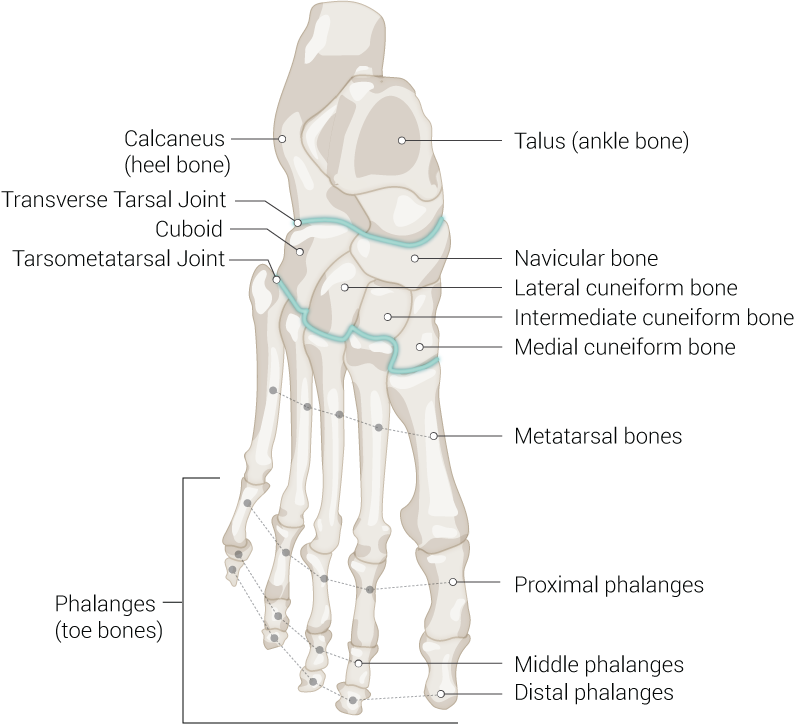

Foot Bones. Anatomy of the foot including talus (ankle bone), navicular bone, lateral cuneiform bone, intermediate cuneiform bone, medial cuneiform bone, metatarsal bones, proximal phalanges, middle phalanges, distal phalanges, phalanges (toe bones), tarsometatarsal joint, cuboid, transverse tarsal joint, and calcaneus (heel bone).

Contributed by Beckie Palmer

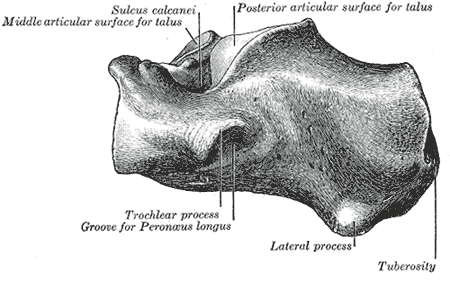

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

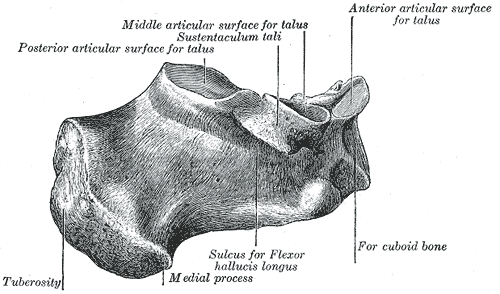

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Keener BJ, Sizensky JA. The anatomy of the calcaneus and surrounding structures. Foot and ankle clinics. 2005 Sep:10(3):413-24 [PubMed PMID: 16081012]

Hall RL, Shereff MJ. Anatomy of the calcaneus. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1993 May:(290):27-35 [PubMed PMID: 8472459]

Cheng X, Wang Y, Qu H, Jiang Y. Ossification processes and perichondral ossification groove of Ranvier: a morphological study in developing human calcaneus and talus. Foot & ankle international. 1995 Jan:16(1):7-10 [PubMed PMID: 7697157]

Bareither D. Prenatal development of the foot and ankle. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 1995 Dec:85(12):753-64 [PubMed PMID: 8592288]

Kumar R, Matasar K, Stansberry S, Shirkhoda A, David R, Madewell JE, Swischuck LE. The calcaneus: normal and abnormal. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1991 May:11(3):415-40 [PubMed PMID: 1852935]

Aparisi Gómez MP, Aparisi F, Bartoloni A, Ferrando Fons MA, Battista G, Guglielmi G, Bazzocchi A. Anatomical variation in the ankle and foot: from incidental finding to inductor of pathology. Part I: ankle and hindfoot. Insights into imaging. 2019 Jul 31:10(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0746-2. Epub 2019 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 31363861]

Adigo AM, Gnakadja NG, Dellanh YY, Adambounou K, Djagnikpo O, Agoda-Kousséma LK, Adoko AL, Adjénou KV. [Haglund deformity: report of three cases]. The Pan African medical journal. 2015:22():37. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.22.37.7866. Epub 2015 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 26664538]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAhn JH, Ahn CY, Byun CH, Kim YC. Operative Treatment of Haglund Syndrome With Central Achilles Tendon-Splitting Approach. The Journal of foot and ankle surgery : official publication of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons. 2015 Nov-Dec:54(6):1053-6. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2015.05.002. Epub 2015 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 26232175]

Carek PJ, Edenfield KM, Michaudet C, Nicolette GW. Foot and Ankle Conditions: Plantar Fasciitis. FP essentials. 2018 Feb:465():11-17 [PubMed PMID: 29381040]

Komatsu F, Takao M, Innami K, Miyamoto W, Matsushita T. Endoscopic surgery for plantar fasciitis: application of a deep-fascial approach. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association of North America and the International Arthroscopy Association. 2011 Aug:27(8):1105-9. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.02.037. Epub 2011 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 21704466]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLowery RB, Calhoun JH. Fractures of the calcaneus. Part I: Anatomy, injury mechanism, and classification. Foot & ankle international. 1996 Apr:17(4):230-5 [PubMed PMID: 8696501]

Lowery RB, Calhoun JH. Fractures of the calcaneus. Part II: Treatment. Foot & ankle international. 1996 Jun:17(6):360-6 [PubMed PMID: 8791085]

Davis D, Seaman TJ, Newton EJ. Calcaneus Fractures. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613611]

Docquier PL, Maldaque P, Bouchard M. Tarsal coalition in paediatric patients. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2019 Feb:105(1S):S123-S131. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2018.01.019. Epub 2018 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 29601967]

Fukuda T, Reddy V, Ptaszek AJ. The infected calcaneus. Foot and ankle clinics. 2010 Sep:15(3):477-86. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2010.04.002. Epub 2010 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 20682417]

Kilgore WB, Parrish WM. Calcaneal tumors and tumor-like conditions. Foot and ankle clinics. 2005 Sep:10(3):541-65, vii [PubMed PMID: 16081020]

Ramponi DR, Baker C. Sever's Disease (Calcaneal Apophysitis). Advanced emergency nursing journal. 2019 Jan/Mar:41(1):10-14. doi: 10.1097/TME.0000000000000219. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30702528]