Introduction

Whether one is a seasoned clinician or a medical student, dizziness can be difficult to diagnose and treat. It affects people of all age ranges with varying symptoms and severity. Additionally, dizziness can be difficult for patients to describe, as it can mean different things to different people. When a patient complains of “dizziness,” they could be describing vertigo, pre-syncope, balance issues, or giddiness. This difficulty in communication can result in frustration for both the patient and the provider; however, differentiating these symptoms is critical for the provider to treat the patient effectively. One critical step for providers is to characterize dizziness as “central vs. peripheral.” Dizziness can account for approximately 5% of walk-in clinics and roughly 4% of emergency department visits.[1] The differential diagnosis for dizziness encompasses numerous body systems, such as neurological, cardiovascular, or hematologic. Some studies have shown up to 15% of cases of dizziness in the emergency department are life-threatening.[1] Therefore, it is important to perform a thorough history, and physical exam, as the ultimate diagnosis can be benign or life-threatening. Symptoms and disease definitions are essential for professional communication between providers, whether they treat patients in the clinic, emergency department, or inpatient setting. The language utilized to describe terms such as ”dizziness” or ”vertigo” can often mean many different things based on one’s interpretations. Therefore, a committee was formed to promote the classification of vestibular disorders. Below are several definitions from the Committee for Classification of Vestibular Disorders to clarify these symptoms:

- Vertigo: A sensation of self-motion when in reality, there is no motion occurring or a perceived sense of motion during a normal head movement.[2]

- Dizziness: A sensation of an impaired or distorted sense of motion relative to spatial orientation.[2]

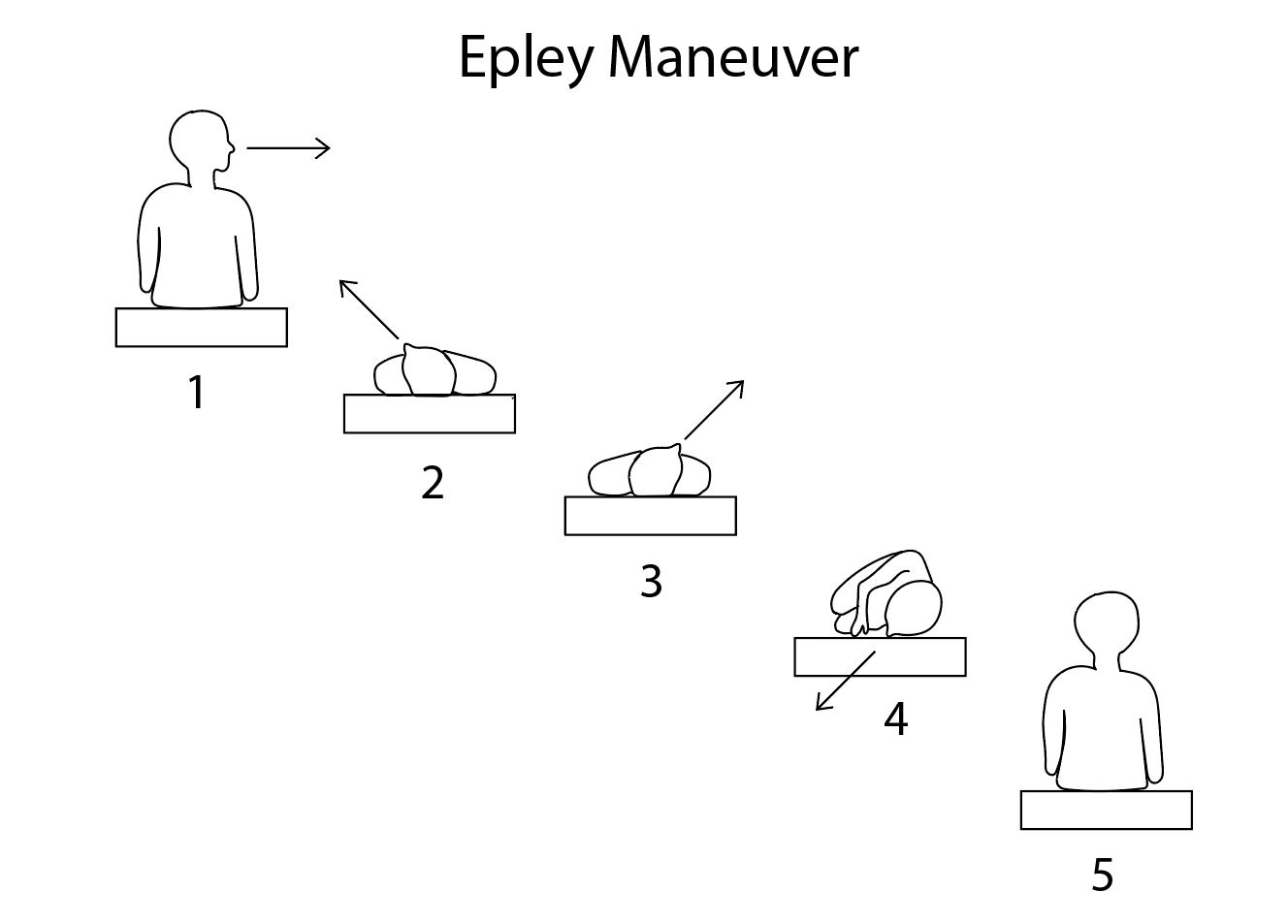

The canalith repositioning maneuver (CRP) was coined by Dr John Epley in response to the need for non-invasive treatment for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV).[3] Prior to the use of CRP, BPPV was often treated surgically. Following the diagnosis of BPPV, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver can localize the otolith. This manuscript will not detail how to perform the Dix-Hallpike maneuver; however, once the otolith is localized, the next step is to perform the CRP (Epley) maneuver. Of note, the endpoint of the Dix-Hallpike maneuver is the beginning of the Epley maneuver; thus, it is imperative to know how to perform both to be effective in diagnosing and treating BPPV correctly. See Image. Epley Maneuver.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

BPPV is among the most common inner ear disorders that cause dizziness or vertigo.[4] The disease process appears to be caused by otoliths that become displaced in the semicircular canal.[5] The majority of these otoliths can be found in the posterior semicircular canal, followed by horizontal (lateral).[5] These otoliths move due to gravity as the head is turning and cause inappropriate signaling that the head is moving when, in reality, it is not. When the vestibular apparatus, semicircular canals, and visual system are disequilibrium, it elicits the sensation of dizziness. The classic symptoms of BPPV often involve brief episodes of rotational vertigo that are reproducible.[6] The most common cause of BPPV is primary or "idiopathic,” as BPPV itself is often found in isolation. However, other inner ear pathologies such as Meniere disease and even migraines have links to BPPV.[7][8] Other common causes include head trauma and inner ear surgeries, which can often dislodge otoliths into the semicircular canals.

Indications

History and physical exams are pertinent in diagnosing BPPV correctly. The classic symptoms of BPPV often include sudden onset vertigo, worsened by head movements. These attacks can last for under one minute. However, patients have described them as lasting much longer due to associated nausea and disequilibrium. When the clinician has diagnosed BPPV, the clinician has likely ruled out more dangerous etiologies of dizziness; it is crucial to communicate with the patient to assuage their fears because many patients present concerned about the more dire causes of dizziness, such as an intracranial mass or a stroke. Following a thorough history and physical exam, and the dizziness determined to be secondary to a peripheral cause, the Dix-Hallpike maneuver can be an option. If the etiology of the dizziness is unknown or if a central lesion is a consideration, other physical exam maneuvers, such as the HiNTS exam, should be employed to further aid in narrowing the differential diagnosis.

Contraindications

There are few contraindications to the Dix-Hallpike maneuver; however, providers need to consider the patient’s physical anatomy and neck mobility concerning their ability to tolerate the quick actions and movements required to perform the maneuver. Patients with cervical spinal stenosis or limited cervical mobility may not tolerate the procedure well due to the quick cervical spine rotation and hyperextension needed for success.[9] In a small study of 50 emergency physicians, barriers that contributed to decreased use of either the Dix-Hallpike maneuver or Epley maneuver included negative experiences associated with performing it, forgetting how to perform the maneuver, or relying on a history of present illness to diagnose BPPV. Overall, these physicians still had positive experiences utilizing the Dix-Hallpike or Epley maneuvers.[10]

Equipment

The absolute equipment required includes:

- Examination table

Optional equipment and materials include:

- Intravenous access equipment

- Premedication with antiemetics such as ondansetron, promethazine, or meclizine

- Emesis bag

- Pillow positioned under the shoulders for hyperextension of the neck

Using antiemetics before the Epley maneuver can provide comfort and temporary relief of nausea and emesis associated with the maneuver.

Personnel

The Epley Maneuver is performable with one operator. Nursing staff can also be available at the bedside should the operator need assistance with moving the patient.

Preparation

Utilize the Dix-Hallpike maneuver prior to performing the Epley Maneuver, as it will allow for localization of the canalith. The following scenario will assume otolith localization to the right inner ear; simply reverse the directions if the otolith is on the contralateral side. A pillow may be placed on the bed and used to allow for the extension of the head past the horizontal.

Positioning: The patient is seated on the exam table, upright. The operator is standing behind the patient, near the head of the bed.

Technique or Treatment

The examiner rotates the patient’s head 45 degrees to the right and quickly lays the head back over the end table. The patient’s eyes should exhibit torsional nystagmus. Each position should be held for at least 30 seconds. As the nystagmus improves, the otolith descends and is in an optimal position for the next step. Rotate the patient’s head 90 degrees to the left, again holding for at least 30 seconds. Instruct the patient to turn their entire head and body in the left lateral position, with the head facing 135 degrees from supine or 225 degrees from the starting position (looking at the floor). Assist the patient in returning back to the sitting supine position while holding their head in place. The head position should be maintained as they are assisted in the sitting position, and repeat if necessary.

Complications

Some complications of using the technique include the inability to tolerate the quick movements needed to perform the maneuver successfully. Neck mobility requires an assessment before the maneuver. The operator should anticipate nausea and emesis; thus, premedication with an antiemetic such as ondansetron or promethazine is optional. In a Cochrane review, nausea was the most commonly cited symptom, which may cause intolerance to the procedure.[11]

Clinical Significance

The Epley maneuver is a low-cost, safe, and relatively benign treatment option for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. It requires few resources and is a simple bedside solution to BPPV, whether in the clinic or emergency department. In a Cochrane review that compared the Epley maneuver to a control or sham maneuver, the Epley had a significant likelihood of symptom resolution (OR, 4.4%; NNT, 3).[11]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The interprofessional team is vital to the treatment of BPPV while using the Epley maneuver. Though the procedure only requires one operator, the situation may require anticipation of adverse side effects to produce satisfactory care. The physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner performing the procedure should anticipate nausea and vomiting; thus, communication with the nursing staff is vital to ensure the patient is either premedicated with an antiemetic or has these medications readily drawn in the event the patient requires it.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

The nursing team should continue to monitor for nausea and vomiting during and after the procedure.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Newman-Toker DE, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA Jr, Pelletier AJ, Butchy GT, Edlow JA. Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2008 Jul:83(7):765-75. doi: 10.4065/83.7.765. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18613993]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBisdorff A, Von Brevern M, Lempert T, Newman-Toker DE. Classification of vestibular symptoms: towards an international classification of vestibular disorders. Journal of vestibular research : equilibrium & orientation. 2009:19(1-2):1-13. doi: 10.3233/VES-2009-0343. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19893191]

Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1992 Sep:107(3):399-404 [PubMed PMID: 1408225]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYou P,Instrum R,Parnes L, Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology. 2019 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 30828628]

Parnes LS, Agrawal SK, Atlas J. Diagnosis and management of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2003 Sep 30:169(7):681-93 [PubMed PMID: 14517129]

Lawson J, Johnson I, Bamiou DE, Newton JL. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: clinical characteristics of dizzy patients referred to a Falls and Syncope Unit. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2005 May:98(5):357-64 [PubMed PMID: 15820968]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKarlberg M, Hall K, Quickert N, Hinson J, Halmagyi GM. What inner ear diseases cause benign paroxysmal positional vertigo? Acta oto-laryngologica. 2000 Mar:120(3):380-5 [PubMed PMID: 10894413]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIshiyama A, Jacobson KM, Baloh RW. Migraine and benign positional vertigo. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2000 Apr:109(4):377-80 [PubMed PMID: 10778892]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBallve Moreno JL, Carrillo Muñoz R, Villar Balboa I, Rando Matos Y, Arias Agudelo OL, Vasudeva A, Bigas Aguilera O, Almeda Ortega J, Capella Guillén A, Buitrago Olaya CJ, Monteverde Curto X, Rodero Perez E, Rubio Ripollès C, Sepulveda Palacios PC, Moreno Farres N, Hernández Sánchez AM, Martin Cantera C, Azagra Ledesma R. Effectiveness of the Epley's maneuver performed in primary care to treat posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014 May 21:15():179. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-179. Epub 2014 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 24886338]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKerber KA, Forman J, Damschroder L, Telian SA, Fagerlin A, Johnson P, Brown DL, An LC, Morgenstern LB, Meurer WJ. Barriers and facilitators to ED physician use of the test and treatment for BPPV. Neurology. Clinical practice. 2017 Jun:7(3):214-224. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000366. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28680765]

Azad T, Pan G, Verma R. Epley Maneuver (Canalith Repositioning) for Benign Positional Vertigo. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2020 Jul:27(7):637-639. doi: 10.1111/acem.13985. Epub 2020 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 32281203]