Introduction

Symptoms of extracranial carotid disease are most often caused by embolization. Arterial emboli account for approximately one-quarter of strokes in Europe and North America, and 80% of these originate from atherosclerotic lesions in a surgically accessible artery in the neck. The most common lesion is at the bifurcation of the carotid artery. Transcranial Doppler studies have shown that emboli are seen in approximately 20% of patients with moderate (> 50% stenosis) lesions at the carotid bifurcation and even higher rates with more than 70% stenoses. The incidence and frequency of emboli are increased in recently symptomatic patients.[1][2][3]

The neurologic dysfunction associated with microemboli may appear as sudden or transient, neurologic symptoms that may include unilateral motor and sensory loss, aphasia (difficulty finding words), or dysarthria (difficulty speaking due to motor dysfunction). These are termed Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA). Most TIAs are brief (minutes). By convention, 24 hours is the arbitrary limit of a TIA. If the symptoms persist, it is a stroke, or cerebrovascular accident (CVA). An embolus to the ophthalmic artery, the first branch of the internal carotid artery, produces a temporary monocular loss of vision called amaurosis fugax or permanent blindness.

Lesions of atherosclerosis in the internal carotid artery occur along the wall of the carotid bulb opposite to the external carotid artery origin. The enlargement of the bulb just distal to this major branch point creates an area of low wall shear stress, flow separation, and loss of unidirectional flow. Presumably, this allows greater interaction of atherogenic particles and the vessel walls at this site and accounts for the localized plaque at the carotid bifurcation.

The accessibility of this localized atheroma allows effective removal of the plaque and a dramatic reduction in stroke risk. Without treatment, 26% of patients with TIAs and more than 70% with carotid artery stenosis will develop permanent neurological impairment (CVA) from continued embolization at two years. The risk of CVA can be reduced to 9% with plaque removal and is usually lower for a patient presenting with amaurosis fugax. [4][5]

Indications

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Indications

- Asymptomatic carotid stenosis > 60% by angiography or 70% by duplex ultrasound.

- Symptomatic carotid stenosis (cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, or amaurosis fugax) > 50%.

- Carotid endarterectomy can be performed safely under regional anesthesia in patients with a severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease (CAD), and other comorbidities.

- Carotid stenting can be considered in patients with a history of neck irradiation, modified radical neck dissection, or reoperative carotid endarterectomy.

- Only patients with concurrent symptomatic carotid stenosis and symptomatic CAD should be considered for combined carotid endarterectomy and coronary artery bypass grafting.

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications other than distal internal artery occlusion.

Personnel

- Vascular surgeon, general surgeon, or neurosurgeon trained at cerebrovascular arterial disease

- Assistant (Resident, Fellow or physician assistant)

- Anesthesiologist

- Nursing Personnel (typically a scrub nurse technician and a circulator nurse)

Preparation

Duplex ultrasound is highly sensitive and specific and is the only preoperative imaging required in most cases.

Arteriography (conventional or CT) is reserved for cases involving restenosis, a history of radiation or prior neck dissection, or atypical findings on duplex ultrasonography.

Patient Positioning

The patient should be in a semi-seated position with a small roll across the shoulder blades. This allows for gentle extension and external rotation of the head to the contralateral side.

The ipsilateral arm is tucked, padding the elbow and wrist.

Care should be taken not to over-rotate or extend the head to avoid kinking of the vertebral arteries or contralateral carotid artery.

Landmarks such as the ear lobe, angle of the mandible, mastoid process, sternal notch, and clavicle must be included in the prepared area.

Technique or Treatment

Carotid endarterectomy can be performed under regional anesthesia, general anesthesia with routine shunting, or general anesthesia with selective shunting based on adjuncts such as intraoperative EEG monitoring or stump pressures.

- Most surgeons prefer an oblique incision along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle. A transverse incision is cosmetically superior and technically feasible for all patients except those with the highest lesions.

- Electrocautery is used to divide the platysma and dissect along the medial border of the SCM muscle from its tendon superiorly to the level of the omohyoid muscle inferiorly. The medial edge of the internal jugular vein (IJV) is identified by sharp dissection.

- Ligation and division of the common facial and the middle thyroid vein inferiorly and any hypoglossal veins superiorly allows for lateral retraction of the SCM and IJV. Great care must be taken to identify the cranial nerves of interest. The vagus nerve usually lies posterolateral to the carotid arteries but can be located anteriorly, placing it at risk of injury early in the dissection.

- The ansa cervicalis can be divided near its origin and followed in a cephalad direction to the hypoglossal nerve. Dissection of the superior thyroid artery should be kept to its origin to avoid injury to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve.

- The common carotid arteries (CCA), external carotid arteries (ECA), and internal carotid arteries (ICA) are circumferentially dissected and encircled with vascular loops. The superior thyroid artery can be looped with a 2-0 silk ligature. The distal ICA can be controlled with a Schwartz clip.

- A long plaque or high carotid bifurcation necessitates additional distal exposure of the ICA; this requires division of the digastric muscle and any underlying crossing veins.

- Cephalad mobilization of the hypoglossal nerve is achieved through ligation and division of the occipital artery and the sternocleidomastoid artery.

- A longitudinal arteriotomy is made, and a shunt of the surgeon's choice is used if indicated. The atheroma is bluntly dissected and elevated in a medial plane. The proximal plaque in a relatively healthy portion of the CCA is sharply cut and the plaque dissected in a cephalad direction toward a finely feathered endpoint.

- Eversion endarterectomy of the ECA is required.

- The bed should be irrigated vigorously with heparinized saline and any remaining loose bits of media removed with fine forceps. If a satisfactory endpoint is not found, the remaining distal plaque can be secured to the vessel with interrupted, full-thickness 7-0 sutures tied on the adventitial surface.

- Once the endarterectomy is complete, a patch of the desired material (Dacron or bovine pericardium) is cut to fit the length and shape of the arteriotomy.

- Prior to completion of the patch angioplasty the shunt is removed, the ICA is allowed to back-bleed, and the atheroma bed is irrigated with heparinized saline.

- Upon completion of the circumferential and continuous suture line, flow is established into the ECA prior to establishing antegrade flow into the ICA.

- The transection plane for eversion carotid endarterectomy is determined by the location of the bulk of the plaque.(a) A type I transection (severe oblique, ICA only) is performed when the bulk of the lesion is located in the ICA.(b) A type II transection (gentle oblique, across the CCA 3 mm below the flow divider) is performed when the bulk of the disease lies within the distal CCA and most proximal portion of the ICA. Lesions extending beyond the proximal 2–3 cm of the ICA are best treated with patch angioplasty rather than eversion.

- Eversion endarterectomy is performed by bluntly developing a circumferential medial plane and continuing it in a cephalad direction while gently pulling back the adventitia with atraumatic forceps.

- The arteriotomy is extended in a caudad direction on the lateral CCA and in a cephalad direction on the medial ICA to allow for an even wider, circumferential anastomosis. Once the ICA portion of the eversion endarterectomy is complete, a shunt may be placed as indicated.

- If the ICA is redundant in length, it may be cut shorter or implanted more proximally on the CCA, making eversion endarterectomy ideal for patients with ICA stenosis in the setting of concurrent ICA elongation.

Postoperative Care

- Closed suction drain overnight, depending on surgeon preference.

- Strict postoperative management of blood pressure, avoiding hypertension to reduce the risk of hyperperfusion syndrome.

- Discharge following overnight observation and monitoring (possibly 8 hours postoperatively if uncomplicated and with satisfactory blood pressure).

Complications

- Cranial nerve injury

- Stroke

- Myocardial infarction

- Carotid restenosis

Clinical Significance

The main purpose of CEA is to prevent stroke. The benefit of CEA depends on low morbidity and mortality rates of the procedure. It is indicated for symptomatic high-grade stenosis, symptomatic moderate stenosis as well as the asymptomatic high-grade stenosis of the internal carotid artery. [6][7][8]

In 1991, the results of the randomized North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) of medical treatment for carotid endarterectomy were reported. All patients had either hemispheric retinal TIAs or nondisabling strokes within 120 days of entry into the trial and 70% to 99% stenosis in the symptomatic carotid artery. The actuarial risk of any ipsilateral stroke at two years was significantly lower at 9% in the 328 surgical patients versus 26% in the 331 medical patients. The data-safety monitoring committee halted further randomization given the widely disparate 18-month follow-up data. For major or fatal ipsilateral strokes, the risk was 2.5% for surgical patients versus 13.1% for medical patients (p < .001). When all strokes and deaths were included, carotid endarterectomy still was better than medical treatment. Subsequent follow-up studies from this trial indicated that the benefit of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients extended to those with even moderate (50% to 69%) carotid artery lesions.

The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study of symptomatic carotid stenosis reported in 1991 results of randomizing 189 men with stenoses greater than 50% to medical or surgical treatment. After one year, there was a significant reduction in stroke or TIAs in the patients having carotid endarterectomy (7.7%) compared with medically treated patients (19.4%), with even more divergent results with carotid stenosis greater than 70%.

The European Carotid Surgery Trial randomized 2518 patients with nondisabling stroke, TIA, or retinal infarction in conjunction with ipsilateral carotid stenosis to medical or surgical treatment. For the 778 patients with stenoses of 70% to 99%, the cumulative risk of stroke at carotid endarterectomy of 7.5%, plus an additional late stroke rate at three years of 2.8%, was less than the 16.8% rate for medically treated patients. At three years the cumulative risk of operative death, operative stroke, ipsilateral ischemic stroke, and any other stroke was 12.3% for the surgical cohort versus 21.9% for the medical group (p < .01). Finally, the risk of fatal or disabling ipsilateral stroke at 3 years was 6.0% for the carotid endarterectomy patients versus 11.0% for the medical control patients (p < .05).

Although the benefit of endarterectomy in these studies was due in part to the high risk of stroke in medically treated patients, the results were significant even in an era when the 30-day combined stroke and death risk of endarterectomy were about 7.5%. Although the combined stroke and death risk of carotid endarterectomy are higher in symptomatic versus asymptomatic patients, the current combined risk is about 2% to 4%.[9][10][11]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There is ample evidence indicating that patients with carotid artery disease with symptoms do benefit from stroke reduction after surgery. Primary care providers and nurse practitioners who encounter patients with carotid artery disease should initially refer these patients to a neurologist. If the patient is deemed to be a candidate for surgery, a vascular surgery consult is needed. Today, the rate of stroke after carotid artery surgery is less than 1% in most institutions. For patients not deemed candidates for open surgery, carotid artery stenting has also been shown to provide comparable results.

Media

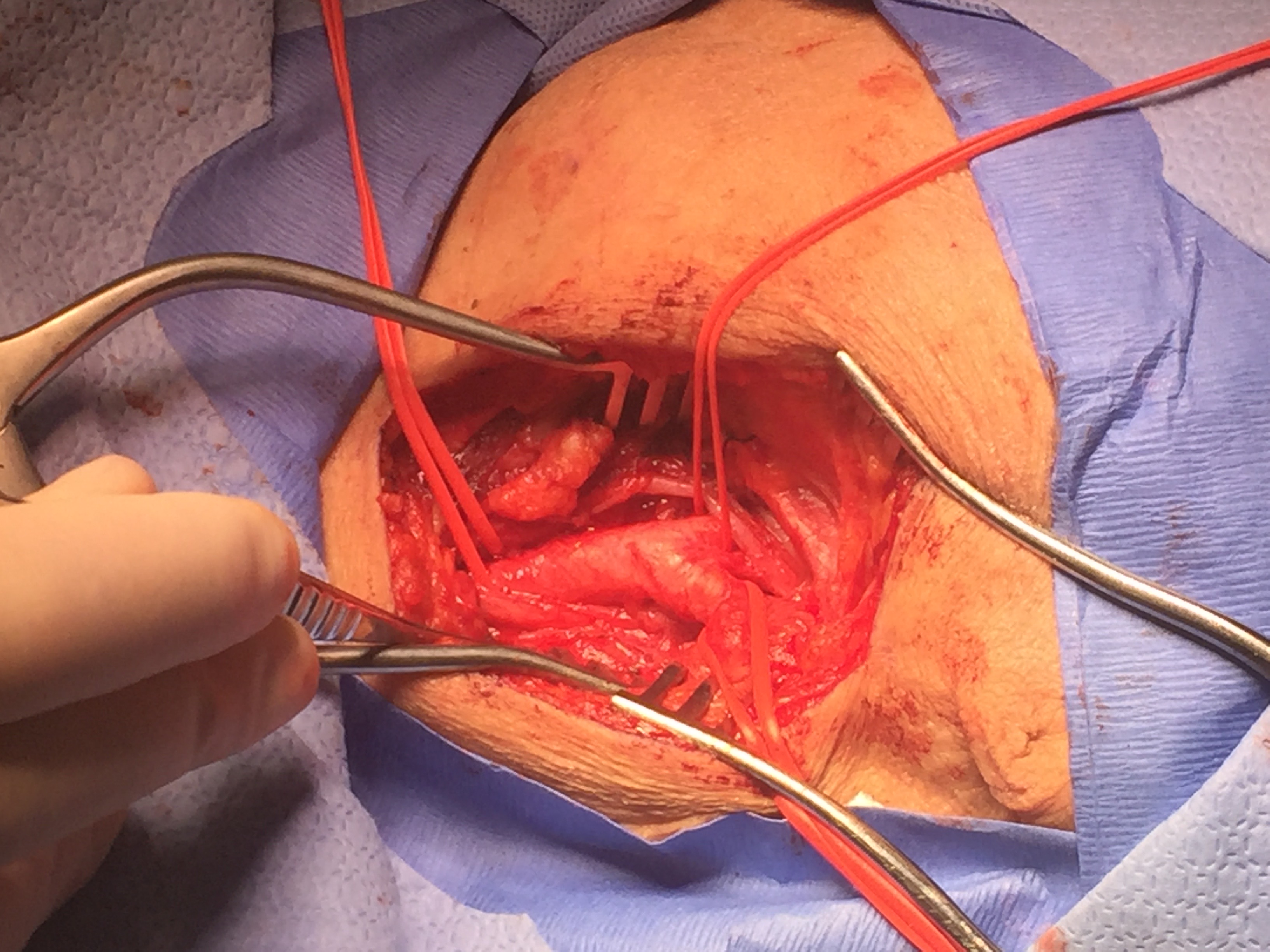

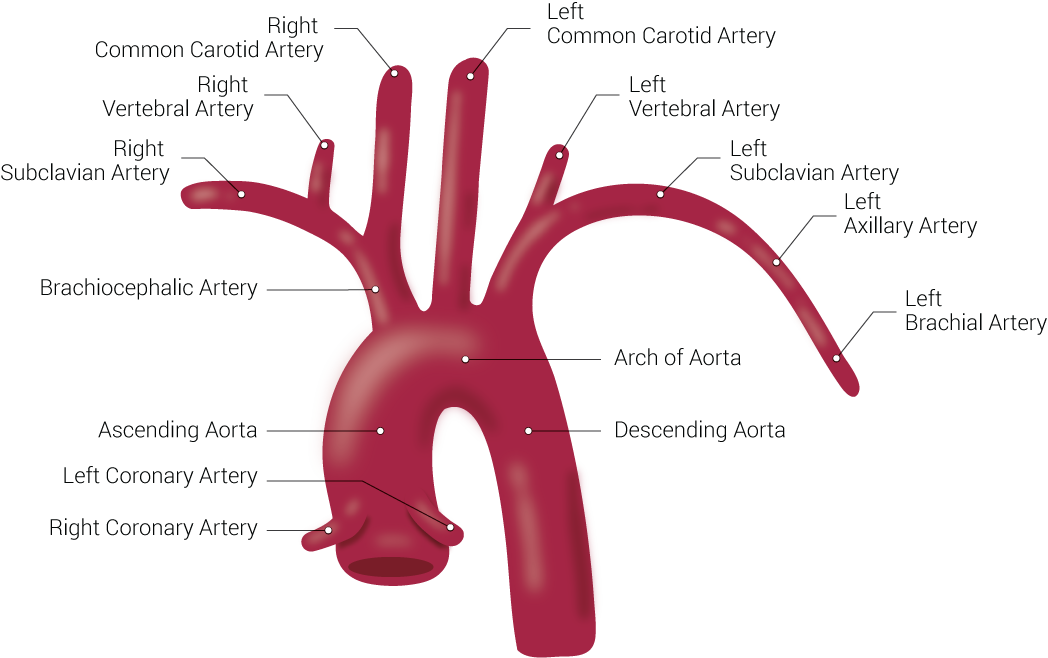

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Branches of the Aorta. This illustration includes the right common carotid artery, right vertebral artery, right subclavian artery, brachiocephalic artery, ascending aorta, left coronary artery, right coronary artery, left common carotid artery, left vertebral artery, left subclavian artery, left axillary artery, left brachial artery, arch of aorta, and descending aorta.

Contributed by Beckie Palmer

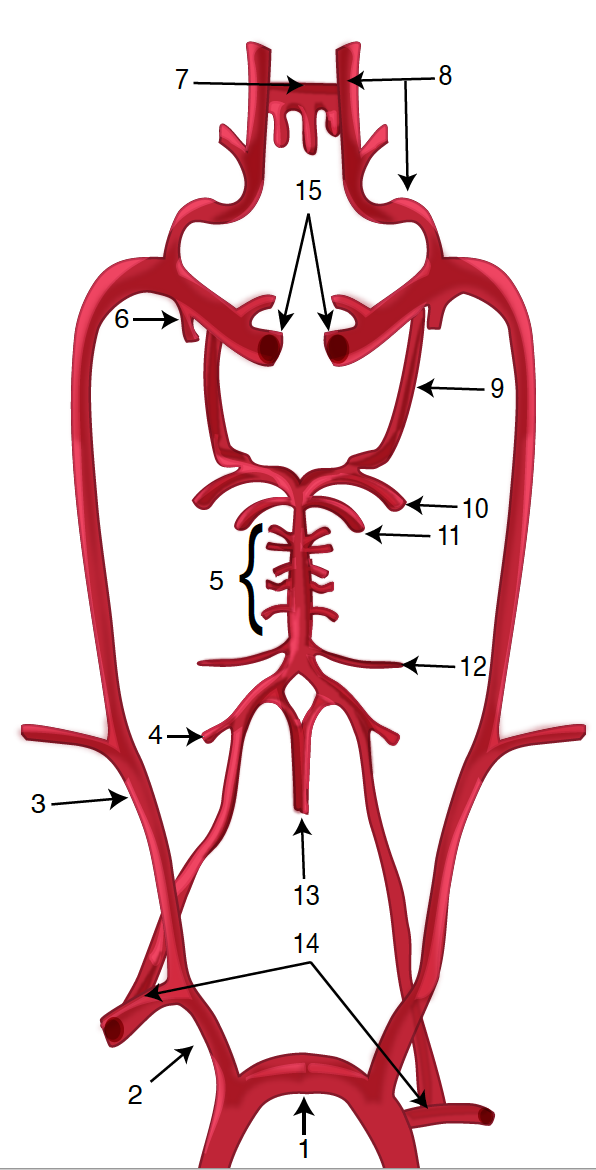

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Diagram of the Brain Blood Circulation. Each number corresponds to the following neuroanatomy: 1) aortic arch; 2) brachiocephalic artery; 3) common carotid artery; 4) posterior inferior cerebellar artery; 5) pontine arteries; 6) anterior choroidal artery; 7) anterior communicating artery; 8) anterior cerebral artery; 9) posterior communicating artery; 10) posterior cerebral artery; 11) superior cerebellar artery; 12) anterior inferior cerebellar artery; 13) anterior spinal artery; 14) arches of vertebral arteries; and 15) internal carotid arteries.

Contributed by O Kuybu, MD

References

Vercelli G, Sorenson TJ, Giordan E, Lanzino G, Rangel-Castilla L. Nuances of carotid artery stenting under flow arrest with dual-balloon guide catheter. Neurosurgical focus. 2019 Jan 1:46(Suppl_1):V4. doi: 10.3171/2019.1.FocusVid.18417. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30611184]

Liao CH, Chen WH, Lee CH, Shen SC, Tsuei YS. Treating cerebrovascular diseases in hybrid operating room equipped with a robotic angiographic fluoroscopy system: level of necessity and 5-year experiences. Acta neurochirurgica. 2019 Mar:161(3):611-619. doi: 10.1007/s00701-018-3769-4. Epub 2019 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 30610374]

Lai Z, Guo Z, Shao J, Chen Y, Liu X, Liu B, Qiu C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of results of simultaneous bilateral carotid artery stenting. Journal of vascular surgery. 2019 May:69(5):1633-1642.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.09.033. Epub 2018 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 30578074]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceArya S, Girotra S. Long-Term Mortality in Carotid Revascularization Patients. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2018 Nov:11(11):e004875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.004875. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30571342]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatelis N, Diakomi M, Maskanakis A, Maltezos K, Schizas D, Papaioannou M. General versus local anesthesia for carotid endarterectomy: Special considerations. Saudi journal of anaesthesia. 2018 Oct-Dec:12(4):612-617. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_10_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30429745]

Murphy SJX, Naylor AR, Ricco JB, Sillesen H, Kakkos S, Halliday A, de Borst GJ, Vega de Ceniga M, Hamilton G, McCabe DJH. Optimal Antiplatelet Therapy in Moderate to Severe Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Carotid Stenosis: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2019 Feb:57(2):199-211. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.09.018. Epub 2018 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 30414802]

McArdle MJ, Abbott AL, Krajcer Z. Carotid Artery Stenosis in Women. Texas Heart Institute journal. 2018 Aug:45(4):243-245. doi: 10.14503/THIJ-18-6711. Epub 2018 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 30374237]

Aber A, Howard A, Woods HB, Jones G, Michaels J. Impact of Carotid Artery Stenosis on Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. The patient. 2019 Apr:12(2):213-222. doi: 10.1007/s40271-018-0337-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30328068]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWang SK, Fajardo A, Sawchuk AP, Lemmon GW, Dalsing MC, Gupta AK, Murphy MP, Motaganahalli RL. Outcomes associated with a transcarotid artery revascularization-centered protocol in high-risk carotid revascularizations using the ENROUTE neuroprotection system. Journal of vascular surgery. 2019 Mar:69(3):807-813. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.06.222. Epub 2018 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 30301690]

Gaba K, Ringleb PA, Halliday A. Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis: Intervention or Best Medical Therapy? Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2018 Sep 24:18(11):80. doi: 10.1007/s11910-018-0888-5. Epub 2018 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 30251204]

Thomas MA, Pearce WH, Rodriguez HE, Helenowski IB, Eskandari MK. Durability of Stroke Prevention with Carotid Endarterectomy and Carotid Stenting. Surgery. 2018 Dec:164(6):1271-1278. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.06.041. Epub 2018 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 30236609]