Introduction

A central venous line (CVL) is a large-bore central venous catheter placed using a sterile technique (unless an urgent clinical scenario prevents sterile technique placement) in specific clinical procedures.[1] Sven-Ivar Seldinger, in 1953, introduced the method to facilitate catheter placement into the lumens of the central veins.[2] Now referred to as the Seldinger technique, this procedure allows the safe and reliable insertion of a central venous catheter in the large lumen central veins. Central line placement is an essential skill, especially in critical care units. According to epidemiologic data, 8% of hospitalized patients require central venous access, and more than 5 million central venous catheters are inserted in the United States annually.[3][4]

Over the past decade, there has been tremendous improvement and reduced complications associated with central line placement procedures. This procedure has become ubiquitous in the intensive care unit with ultrasound guidance, standardized techniques, new catheter designs, and central line care bundles. This topic details the anatomy of the site placement, indications and contraindications, equipment and personnel involved, technique, preparation, and associated complications.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

There are 3 possible sites for CVL placement in adult patients: the internal jugular, femoral, and subclavian. The right internal jugular and subclavian valves are the most direct paths to the right atrium via the superior vena cava. The femoral veins are compressible sites and, as such, may be more appropriate for patients who are at high risk of bleeding. The subclavian vein approach is at higher risk for pneumothorax than the internal jugular vein approach. Ultrasound guidance can benefit all approaches and is recommended for every CVL placement. However, when ultrasound guidance is not feasible, CVLs may be placed using anatomical landmarks without ultrasound.

Internal Jugular Vein Access

The internal jugular vein exits the skull base from the jugular foramen, collecting blood from the sigmoid sinus. It is contained within the carotid sheath and travels with the carotid artery and the vagus nerve. As it travels towards the chest, it assumes an anterolateral position to the common carotid artery beneath the sternocleidomastoid muscle.[5] Caudal to the cricoid cartilage, the internal jugular vein can be found between the 2 heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle at the base of the neck.[6] Here, the vein is most superficial, located only 1 to 1.5 cm below the skin surface in most patients.[6] As it courses forward, it joins the subclavian vein to form the brachiocephalic (innominate) vein.[6]

Right internal jugular venous access allows a straight and direct path to the superior vena cava and has a low rate of catheter malposition during placement.[7] It is often the preferred site of access for CVL placement. Contraindications to internal jugular venous access include severe coagulopathy, the presence of another device at the site, and altered local anatomy, especially if there is a concern for thrombosis from initial catheter placement.[7]

Subclavian Vein Access

Lateral to the suprasternal notch, the clavicle has an anterior convexity in the medial two-thirds of the bone and an anterior concavity in the lateral third. The center of this anterior convexity is known as the "bend" of the clavicle and is an essential landmark in the infraclavicular approach to subclavian vein access. The subclavian vein can be found by inserting the needle 2 to 3 cm inferior to the midpoint of the clavicle, which is 1 to 2 cm lateral to the "bend" of the clavicle.[8] The subclavian vein forms from the axillary vein, arching cephalad behind the medial clavicle, and slopes caudally. It joins the internal jugular vein to form the brachiocephalic (innominate) vein posterior to the sternoclavicular joint. The subclavian artery is superior and posterior to the subclavian vein, separated by the anterior scalene muscle. Using the infraclavicular approach, the lung is deep and inferior to the access point of the subclavian vein. The phrenic nerve is located inferiorly, and the brachial plexus is superior. The left-sided thoracic and right-sided lymphatic ducts are posterior to the subclavian vein.

The subclavian vein access site is incompressible and, as such, should be avoided in patients with severe coagulopathy and an increased risk of bleeding.[9] However, a retrospective analysis of patients with bleeding disorders who required central line placement revealed that CVLs could be safely performed in these patients when performed by expert hands.[9]

Femoral Vein Access

The common femoral vein is located superficially at the femoral triangle, just distal to the inguinal ligament. It is located within the femoral sheath and lies medial to the femoral artery within the femoral triangle. The femoral artery pulsation is used as an anatomic landmark to find the common femoral vein. The mid-inguinal point between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic tubercle is lateral to this pulsation. This landmark can be used when the femoral artery is not palpable.

The femoral vein access site is more prone to catheter-related deep vein thrombosis than jugular or subclavian access sites.[10] This access site was considered at higher risk of catheter-related infections; however, recent studies have shown that catheter-related infections are similar at all 3 sites when optimal insertion points are selected, and the procedure is performed using strict sterile techniques by expert hands.[11][12] Still, current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend avoiding femoral site access unless the internal jugular and subclavian sites are unavailable.

Indications

Indications for placing a CVL include the following:

- Drug infusions that could otherwise cause phlebitis or sclerosis (eg, vasopressors and hyperosmolar solutions)

- Monitoring

- Central venous pressure

- Central venous oxyhemoglobin saturation (ScvO2)

- Pulmonary artery pressure

- Emergency venous access (due to difficult peripheral intravenous access)

- Transvenous pacing wire placement

- High-volume/flow procedures requiring large-bore access (hemodialysis and plasmapheresis)

- Vena cava filter placement

- Venous thrombolytic therapy [13][14]

Contraindications

Contraindications for central venous access are always relative and dependent on the urgency and alternative venous access. Site-specific contraindications include distorted local anatomy, skin infection overlying the insertion site, thrombus within the intended vein, or other indwelling intravascular hardware within the intended vessel. Coagulopathy and bleeding disorders are considered relative contraindications even when they are severe. A systematic review studying the risk of complications following CVL placement in patients with moderate-to-severe coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia revealed that the incidence of major bleeding complications is low, and evidence supporting the correction of coagulopathy before CVL placement is lacking.[15] Ultrasound-guided placement of CVL is the method of choice in patients at high risk of bleeding due to underlying disorders of hemostasis, as it allows for safe and reliable access to central veins with low rates of complications and fewer attempts in patients with these disorders.[16]

It still needs to be determined what thresholds of platelet count, international normalized ratio (INR), and partial thromboplastin time central venous catheterization can safely be performed. According to recent data, thrombocytopenia appears to pose a greater risk when compared with prolonged clotting times.[17][18] Despite common concerns and practice, limited evidence supports the routine correction of coagulopathy before central venous cannulation.[10][15][19][20] Retrospective studies suggest no pre-procedure reversal warrants platelet count > 20 x 10/L and INR < 3.[10] For severe coagulopathy (eg, platelet count <20 x 10/L and INR >3), administration of a pre-procedure blood product (eg, platelets, fresh frozen plasma) should be considered when time allows. Based on the clinical decision, the benefit of pre-procedure replacement should outweigh the risk.

Equipment

Most central line kits include:

- Syringe and needle for local anesthetic

- A small vial of 1% lidocaine

- Syringe and introducer needle

- Scalpel

- Guidewire

- Tissue dilator

- Sterile dressing

- Suture and needle

- Central line catheter (of which there are several types and sizes, including triple-lumen, double-lumen, and large bore single-lumen)(See Image. Central Line, Triple Lumen).

In addition, the operator requires a sterile gown, cap, gloves, sterile gauze, sterile saline, face mask, and a sterile cleansing solution such as chlorhexidine. The operator should also ensure that ultrasound, sterile ultrasound gel, and a sterile ultrasound probe are part of the setup.[13] A 16-cm CVL should prevent intracardiac placement and arrhythmias when cannulating the subclavian or internal jugular veins.[7]

Personnel

The personnel required to pass the central venous catheter are the proceduralist, technician, and nurse.

Preparation

Nontunneled central venous catheters are usually placed at the bedside. In most cases, informed consent needs to be obtained before the procedure. In an emergency, however, consent is implied. The proceduralist should convey the procedure indication, plan, benefits, and potential complications (eg, pneumothorax) to the patient and legal guardian. The need to perform another procedure, such as placing a chest tube for pneumothorax, should also be conveyed while taking consent. An appropriate position of the patient for the selected site is necessary. In the case of the internal jugular and subclavian access, a 15-degree Trendelenburg position should be obtained if feasible according to the clinical situation. This position also minimizes the risk of venous air embolism during the procedure.[17] In the femoral approach, the patient should be lying supine. Continuous cardiac rhythm monitoring and pulse oximetry of the patient's telemetry are necessary during the procedure.

Precannulation vein assessment via bedside ultrasonography is recommended to help identify relevant anatomy before the procedure and to help select the most appropriate site for the patient.[18]

A strict aseptic technique for site preparation and the operator is required. Surgical antiseptic hand wash, long-sleeved sterile gown, surgical mask, gloves, and head covering are required for the operator.[13] An antiseptic skin preparation solution should be used to clean the access site. Chlorhexidine-alcohol-based solutions with more than 0.5% chlorhexidine are preferred over povidone-iodine solutions due to their superior performance.[19] Systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis before this procedure is not recommended as it does not decrease the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infections.[20]

The patient should be covered in a sterile drape large enough to cover the entire patient, exposing only the cleaned access site. The ultrasound probe and gel should be placed in a sterile sheath with the help of a bedside assistant in a sterile fashion. By the end of the procedure, a timeout should be called with the assistant to confirm the patient, procedure, and site of the procedure.

SICSAG and HPS published the central venous catheter placement insertion bundle and associated tools in May 2007. If addressed, this bundle has 5 key aspects that minimize the risk of catheter-related bloodstream infection.[21]

| S No | Central line insertion bundle |

| 1 | Insertion checklist and documentation |

| 2 | Hand hygiene and maximum barrier precautions |

| 3 | Catheter site selection |

| 4 | Skin antisepsis |

| 5 | Dressing |

Technique or Treatment

The technique used for central line placement includes the following:

- Infiltrate the skin with 1% lidocaine for local anesthesia around the needle insertion site.

- A sterile ultrasound conduction medium and bedside ultrasound were used to identify the target vein. The vein appears round with a black center that is easily collapsable under pressure applied to the probe. The adjacent artery (carotid or femoral) has apparent pulsations and minimal collapsibility.

- If using landmarks, then follow the site-specific guidelines described below:

- For internal jugular vein CVL (central approach), the needle should be inserted at the triangle's apex formed by the sternocleidomastoid muscle's 2 heads above the medial clavicle and is usually 5 cm superior to the clavicle. The needle should be inserted at 30 to 45 degrees into the skin. This should be lateral to the carotid pulsation, and the needle should be directed laterally in the sagittal plane towards the ipsilateral nipple.[22] Turning the patient's head to the contralateral side accentuates landmarks and facilitates CVL placement.

- For the subclavian vein CVL (infraclavicular approach), the needle should be inserted approximately 2 to 3 cm inferior to the midpoint of the clavicle, which is 1 to 2 cm lateral to the "bend." The needle should be directed posterior to the suprasternal notch.[8] An insertion that is lateral to the midclavicular line is preferred.[8] The needle should be advanced under the clavicle and parallel to the clavicle in the coronal plane. The vein is accessed as the needle passes beneath the junction of the middle and medial thirds of the clavicle.

- For femoral line CVL, the needle insertion site should be approximately 1 to 3 cm below the inguinal ligament and 0.5 to 1 cm medial where the femoral artery pulsates.

- Insert the introducer needle with negative pressure until venous blood is aspirated. For the subclavian CVL, insert the needle at an angle as close to parallel to the skin as possible until making contact with the clavicle, then advance the needle under and along the inferior aspect of the clavicle. Next, direct the needle tip towards the suprasternal notch until venous blood is aspirated. Whenever possible, the introducer needle should be advanced under ultrasound guidance to ensure the tip does not enter the incorrect vessel or puncture through the distal edge of the vein.

- Once venous blood is aspirated, stop advancing the needle. Carefully remove the syringe and thread the guidewire through the introducer needle hub. The guidewire should only be inserted beyond the anticipated catheter length, avoiding intracardiac advancement. The telemetry monitor should be carefully watched to identify any arrhythmias the guidewire induces. If an arrhythmia does occur, the guidewire should be pulled back until it resolves.[2]

- The average distance from a right internal jugular access site to the cavoatrial junction is 16 cm.[23] The average distance to the cavoatrial junction from the right subclavian access site, the left subclavian access site, and the left internal jugular access site are 18.4 cm, 21.2 cm, and 19.1 cm, respectively.[23] In most cases, 18 cm should be considered the upper limit of normal for guidewire length insertion regardless of the access site in subclavian and internal jugular cannulation. The guidewire should be advanced 25 cm for femoral access sites to ensure catheter placement within the inferior vena cava.

- Care is necessary to properly orient the J-tip guidewire when placing a subclavian venous catheter. In an infraclavicular approach, the bevel of the needle should be directed caudally to ensure adequate placement in the superior vena cava instead of internal jugular placement.[3]

- While holding the guidewire in place, remove the introducer needle hub.

- If possible, use the ultrasound to confirm the guidewire is in the target vessel in 2 different views.

- Next, use the scalpel tip to stab the skin against the wire, just large enough to accommodate the dilator. Insert the dilator with a twisting motion. The dilator only needs to be advanced to the anticipated depth of the targeted vein without dilating the vein itself. In an internal jugular venous access, this is usually 3 to 4 cm, and for subclavian access, this is usually 3 to 5 cm.[24]

- Advance the CVL over the guidewire. Ensure the distal lumen of the central line is uncapped to facilitate the passage of the guidewire. As discussed above, insertion length should be considered when placing the catheter. For most adults, 16 to 18 cm for right-sided and 20 cm for left-sided jugular catheters is sufficient.[25] Right-side subclavian venous catheters are generally placed at 16 cm, and left-sided catheters are placed at a depth of 20 cm.[25] Femoral venous catheters are placed at a length of 15 to 30 cm.

- Once the CVL is in place, remove the guidewire. Next, flush and aspirate all ports with sterile saline.

- Secure the CVL with sutures and place a sterile dressing over the site.

- The sterile dressing is placed over the exit site of the catheter.

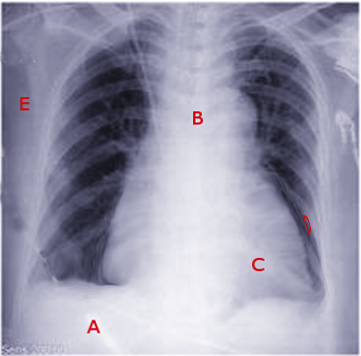

- Confirmation of the catheter tip position with chest radiography is required before use when internal jugular and subclavian access is obtained.[26]

Complications

The overall rate of complications in central venous line placements is reportedly around 15%.[4] Mechanical difficulties are often operator-dependent and occur at a reported rate of 33%.[27]

Complications of CVL placements include arterial puncture, catheter malposition, pneumothorax, subcutaneous hematoma, hemothorax, and cardiac arrest (exceedingly rare). The use of real-time ultrasound guidance can significantly decrease the complication rates of this procedure.[28]

Periprocedural Complications

Pneumothorax is a severe complication of subclavian and internal jugular vein catheter placements. However, the internal jugular approach is associated with a lower rate of pneumothorax.[29] Venous air embolism, though potentially fatal, is an infrequent complication of this procedure and can be minimized by correctly positioning the patient and using diaphragms that prevent significant air embolism.[30] Arterial puncture and injury are severe complications of this procedure, and every effort should be made to avoid their occurrence. As stated above, consistent use of real-time ultrasonography can prevent this complication. If arterial trauma and cannulation occur, endovascular treatment is the best approach to minimize hematoma, airway obstruction, stroke, and false aneurysm.[31]

If inadvertent arterial cannulation with a catheter occurs, it is better to leave the catheter in place and attempt treatment with a percutaneous closure device.[32] Ventricular arrhythmias are known complications of this procedure and are related to the placement of the guidewire and catheter tip beyond the cavoatrial junction.[33] Careful monitoring of the guidewire length as it is advanced into the vessel and determining adequate catheter length before securing it can avoid this potentially lethal complication.

Late Complications

Catheter-related bloodstream infections (CR-BSI) are well-recognized complications of this procedure and are associated with increased morbidity and mortality for the patient.[34] The most critical risk factor for these infections is a longer duration of use, especially in dialysis patients.[35] Sequalae of CR-BSI include metastatic infections to vertebral bone or disc space, endocarditis, and endovascular infections. [34]

Central vein stenosis is another late complication of this procedure and is most prominent in chronic hemodialysis patients who often undergo repeated cannulations of the central veins. The highest risk of this complication occurs in the left-sided internal jugular or subclavian vein cannulations.[36] Other risk factors include using hemodialysis catheters instead of flexible triple-lumen catheters and a longer catheter-dwelling time.[36] In addition to central venous stenosis, catheter-related deep vein thrombosis (DVT) can occur. Catheter-related DVT is most common in patients with underlying malignancy and using peripherally inserted multi-lumen catheters.[37] The table below summarizes the early and late complications associated with central venous line placement (see Image. Central Line, Pericardium).

| S No | Complications Associated with Central Venous Placement |

| Early |

BleedingArterial punctureArrhythmiaAir embolismThoracic duct injuryMalpositioning of catheterPneumothoraxHaemothorax |

| Late | InfectionVenous thrombosisCentral vein stenosisPulmonary embolismVenous stasisCatheter malfunctionCatheter migrationCatheter embolizationMyocardial perforationNerve injury |

Clinical Significance

Clinical pearls for consideration:

- A chest X-ray should be performed immediately for the internal jugular and subclavian lines to ensure proper placement and the absence of an iatrogenic pneumothorax.

- Be sure you withdraw venous blood before dilation and cannulation of the vessel.

- If the internal jugular CVL attempt fails, move to the ipsilateral subclavian vein. Never attempt the opposite side without a chest X-ray or ultrasound first to avoid bilateral pneumothoraces.

- Never force the guidewire on insertion because it may damage the vessel or surrounding structures. Forcing the wire could also cause it to kink, making removal difficult and damaging the vessel wall. It may also lead to an inaccurate position of the catheter.

- Always place your finger over the open hub of the needle to prevent an air embolism.

- Always confirm placement with ultrasound, looking for the needle's reverberation artifact and tenting of the vessel wall. Needles cannot be visualized on ultrasound, but wires can be visualized, so the operator can also confirm at that step.

- A venous blood gas can be aspirated off a femoral line to ensure it is not arterial.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Central line placement is a common procedure, often done at the bedside. Placement under strict sterile conditions, subsequent catheter management, and a daily review of the need to continue the central catheter can help minimize complications associated with this procedure. This requires an interprofessional team of clinicians. The critical care nurse must perform daily dressing inspections, periodically change the dressing following strict aseptic technique to prevent catheter-related infections, and report to the clinician managing the case if any concerns arise so corrective action(s) can be taken. An aseptic technique is also required when accessing the ports of the CVL.

Depending on the line's location, complications like pneumothorax, hematoma, bleeding, or extravasation can occur and should be monitored. Healthcare workers should generally avoid lines in the groin for more than 24 to 48 hours as they are prone to infections, making it difficult for the patient to ambulate or get out of bed. To ensure good practice and limit complications, most hospitals now have an interprofessional team of healthcare professionals in charge of central line insertion and monitoring, each checking and communicating any issues noted to the rest of the team so corrective action can occur if necessary. This universal practice has been shown to limit complications and optimize clinical outcomes for patients undergoing this procedure.[38][39] In the event of an infection, an infectious disease specialty pharmacist may be consulted to best target antimicrobial therapy.

Media

References

Mitsuda S, Tokumine J, Matsuda R, Yorozu T, Asao T. PICC insertion in the sitting position for a patient with congestive heart failure: A case report. Medicine. 2019 Feb:98(6):e14413. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000014413. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30732193]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSELDINGER SI. Catheter replacement of the needle in percutaneous arteriography; a new technique. Acta radiologica. 1953 May:39(5):368-76 [PubMed PMID: 13057644]

Ruesch S, Walder B, Tramèr MR. Complications of central venous catheters: internal jugular versus subclavian access--a systematic review. Critical care medicine. 2002 Feb:30(2):454-60 [PubMed PMID: 11889329]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcGee DC, Gould MK. Preventing complications of central venous catheterization. The New England journal of medicine. 2003 Mar 20:348(12):1123-33 [PubMed PMID: 12646670]

Turba UC, Uflacker R, Hannegan C, Selby JB. Anatomic relationship of the internal jugular vein and the common carotid artery applied to percutaneous transjugular procedures. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2005 May-Jun:28(3):303-6 [PubMed PMID: 15770389]

Denys BG, Uretsky BF. Anatomical variations of internal jugular vein location: impact on central venous access. Critical care medicine. 1991 Dec:19(12):1516-9 [PubMed PMID: 1959371]

McGee WT, Moriarty KP. Accurate placement of central venous catheters using a 16-cm catheter. Journal of intensive care medicine. 1996 Jan-Feb:11(1):19-22 [PubMed PMID: 10160067]

Tan BK, Hong SW, Huang MH, Lee ST. Anatomic basis of safe percutaneous subclavian venous catheterization. The Journal of trauma. 2000 Jan:48(1):82-6 [PubMed PMID: 10647570]

Mumtaz H, Williams V, Hauer-Jensen M, Rowe M, Henry-Tillman RS, Heaton K, Mancino AT, Muldoon RL, Klimberg VS, Broadwater JR, Westbrook KC, Lang NP. Central venous catheter placement in patients with disorders of hemostasis. American journal of surgery. 2000 Dec:180(6):503-5; discussion 506 [PubMed PMID: 11182407]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGe X, Cavallazzi R, Li C, Pan SM, Wang YW, Wang FL. Central venous access sites for the prevention of venous thrombosis, stenosis and infection. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012 Mar 14:2012(3):CD004084. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004084.pub3. Epub 2012 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 22419292]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDeshpande KS, Hatem C, Ulrich HL, Currie BP, Aldrich TK, Bryan-Brown CW, Kvetan V. The incidence of infectious complications of central venous catheters at the subclavian, internal jugular, and femoral sites in an intensive care unit population. Critical care medicine. 2005 Jan:33(1):13-20; discussion 234-5 [PubMed PMID: 15644643]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceParienti JJ, Thirion M, Mégarbane B, Souweine B, Ouchikhe A, Polito A, Forel JM, Marqué S, Misset B, Airapetian N, Daurel C, Mira JP, Ramakers M, du Cheyron D, Le Coutour X, Daubin C, Charbonneau P, Members of the Cathedia Study Group. Femoral vs jugular venous catheterization and risk of nosocomial events in adults requiring acute renal replacement therapy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008 May 28:299(20):2413-22. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2413. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18505951]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAmerican Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Central Venous Access, Rupp SM, Apfelbaum JL, Blitt C, Caplan RA, Connis RT, Domino KB, Fleisher LA, Grant S, Mark JB, Morray JP, Nickinovich DG, Tung A. Practice guidelines for central venous access: a report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Central Venous Access. Anesthesiology. 2012 Mar:116(3):539-73. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31823c9569. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22307320]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBodenham Chair A, Babu S, Bennett J, Binks R, Fee P, Fox B, Johnston AJ, Klein AA, Langton JA, Mclure H, Tighe SQ. Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland: Safe vascular access 2016. Anaesthesia. 2016 May:71(5):573-85. doi: 10.1111/anae.13360. Epub 2016 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 26888253]

van de Weerdt EK, Biemond BJ, Baake B, Vermin B, Binnekade JM, van Lienden KP, Vlaar APJ. Central venous catheter placement in coagulopathic patients: risk factors and incidence of bleeding complications. Transfusion. 2017 Oct:57(10):2512-2525. doi: 10.1111/trf.14248. Epub 2017 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 28856685]

Tercan F, Ozkan U, Oguzkurt L. US-guided placement of central vein catheters in patients with disorders of hemostasis. European journal of radiology. 2008 Feb:65(2):253-6 [PubMed PMID: 17482407]

Ely EW, Hite RD, Baker AM, Johnson MM, Bowton DL, Haponik EF. Venous air embolism from central venous catheterization: a need for increased physician awareness. Critical care medicine. 1999 Oct:27(10):2113-7 [PubMed PMID: 10548191]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGornik HL, Gerhard-Herman MD, Misra S, Mohler ER 3rd, Zierler RE, Peripheral Vascular Ultrasound and Physiological Testing Part II: Testing for Venous Disease and Evaluation of Hemodialysis Access Technical Panel, Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. ACCF/ACR/AIUM/ASE/IAC/SCAI/SCVS/SIR/SVM/SVS/SVU 2013 appropriate use criteria for peripheral vascular ultrasound and physiological testing part II: testing for venous disease and evaluation of hemodialysis access: a report of the american college of cardiology foundation appropriate use criteria task force. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013 Aug 13:62(7):649-65. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.001. Epub 2013 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 23876422]

Mimoz O, Lucet JC, Kerforne T, Pascal J, Souweine B, Goudet V, Mercat A, Bouadma L, Lasocki S, Alfandari S, Friggeri A, Wallet F, Allou N, Ruckly S, Balayn D, Lepape A, Timsit JF, CLEAN trial investigators. Skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone iodine-alcohol, with and without skin scrubbing, for prevention of intravascular-catheter-related infection (CLEAN): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, two-by-two factorial trial. Lancet (London, England). 2015 Nov 21:386(10008):2069-2077. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00244-5. Epub 2015 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 26388532]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJohnson E, Babb J, Sridhar D. Routine Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Totally Implantable Venous Access Device Placement: Meta-Analysis of 2,154 Patients. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2016 Mar:27(3):339-43; quiz 344. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.11.051. Epub 2016 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 26776446]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTang HJ, Lin HL, Lin YH, Leung PO, Chuang YC, Lai CC. The impact of central line insertion bundle on central line-associated bloodstream infection. BMC infectious diseases. 2014 Jul 1:14():356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-356. Epub 2014 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 24985729]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHo AM, Ricci CJ, Ng CS, Critchley LA, Ho AK, Karmakar MK, Cheung CW, Ng SK. The medial-transverse approach for internal jugular vein cannulation: an example of lateral thinking. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2012 Feb:42(2):174-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.05.033. Epub 2011 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 22056111]

Andrews RT, Bova DA, Venbrux AC. How much guidewire is too much? Direct measurement of the distance from subclavian and internal jugular vein access sites to the superior vena cava-atrial junction during central venous catheter placement. Critical care medicine. 2000 Jan:28(1):138-42 [PubMed PMID: 10667513]

Robinson JF, Robinson WA, Cohn A, Garg K, Armstrong JD 2nd. Perforation of the great vessels during central venous line placement. Archives of internal medicine. 1995 Jun 12:155(11):1225-8 [PubMed PMID: 7763129]

Polderman KH, Girbes AJ. Central venous catheter use. Part 1: mechanical complications. Intensive care medicine. 2002 Jan:28(1):1-17 [PubMed PMID: 11818994]

Abood GJ, Davis KA, Esposito TJ, Luchette FA, Gamelli RL. Comparison of routine chest radiograph versus clinician judgment to determine adequate central line placement in critically ill patients. The Journal of trauma. 2007 Jul:63(1):50-6 [PubMed PMID: 17622868]

Eisen LA, Narasimhan M, Berger JS, Mayo PH, Rosen MJ, Schneider RF. Mechanical complications of central venous catheters. Journal of intensive care medicine. 2006 Jan-Feb:21(1):40-6 [PubMed PMID: 16698743]

Stone MB, Nagdev A, Murphy MC, Sisson CA. Ultrasound detection of guidewire position during central venous catheterization. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2010 Jan:28(1):82-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.09.019. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20006207]

Vinson DR, Ballard DW, Hance LG, Stevenson MD, Clague VA, Rauchwerger AS, Reed ME, Mark DG, Kaiser Permanente CREST Network Investigators. Pneumothorax is a rare complication of thoracic central venous catheterization in community EDs. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2015 Jan:33(1):60-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.10.020. Epub 2014 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 25455050]

Beathard GA, Litchfield T, Physician Operators Forum of RMS Lifeline, Inc. Effectiveness and safety of dialysis vascular access procedures performed by interventional nephrologists. Kidney international. 2004 Oct:66(4):1622-32 [PubMed PMID: 15458459]

Guilbert MC, Elkouri S, Bracco D, Corriveau MM, Beaudoin N, Dubois MJ, Bruneau L, Blair JF. Arterial trauma during central venous catheter insertion: Case series, review and proposed algorithm. Journal of vascular surgery. 2008 Oct:48(4):918-25; discussion 925. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.04.046. Epub 2008 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 18703308]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNicholson T, Ettles D, Robinson G. Managing inadvertent arterial catheterization during central venous access procedures. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2004 Jan-Feb:27(1):21-5 [PubMed PMID: 15109223]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePittiruti M, Lamperti M. Late cardiac tamponade in adults secondary to tip position in the right atrium: an urban legend? A systematic review of the literature. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2015 Apr:29(2):491-5. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2014.05.020. Epub 2014 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 25304887]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLok CE, Mokrzycki MH. Prevention and management of catheter-related infection in hemodialysis patients. Kidney international. 2011 Mar:79(6):587-598. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.471. Epub 2010 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 21178979]

Lee T, Barker J, Allon M. Tunneled catheters in hemodialysis patients: reasons and subsequent outcomes. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2005 Sep:46(3):501-8 [PubMed PMID: 16129212]

Agarwal AK. Central vein stenosis: current concepts. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2009 Sep:16(5):360-70. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2009.06.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19695504]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGeerts W. Central venous catheter-related thrombosis. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2014 Dec 5:2014(1):306-11. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2014.1.306. Epub 2014 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 25696870]

Levit O, Shabanova V, Bizzarro M. Impact of a dedicated nursing team on central line-related complications in neonatal intensive care unit. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2020 Aug:33(15):2618-2622. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1555814. Epub 2019 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 30612486]

Chick JF, Reddy SN, Yam BL, Kobrin S, Trerotola SO. Institution of a Hospital-Based Central Venous Access Policy for Peripheral Vein Preservation in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A 12-Year Experience. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2017 Mar:28(3):392-397. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2016.11.007. Epub 2017 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 28111198]