Introduction

In the United States, more than 5 million central venous catheters are inserted every year for a variety of indications in both hospitalized and surgical patients. Once an indication for central venous catheterization is established, the clinician has multiple sites to select from including the internal jugular vein, subclavian vein, femoral vein or a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC). Subclavian catheters can be temporary or permanent, simple, tunneled, or connected to a port under the skin. Subclavian catheters may be single or multiple lumens, and the diameter of the catheter is also variable.[1][2][3]

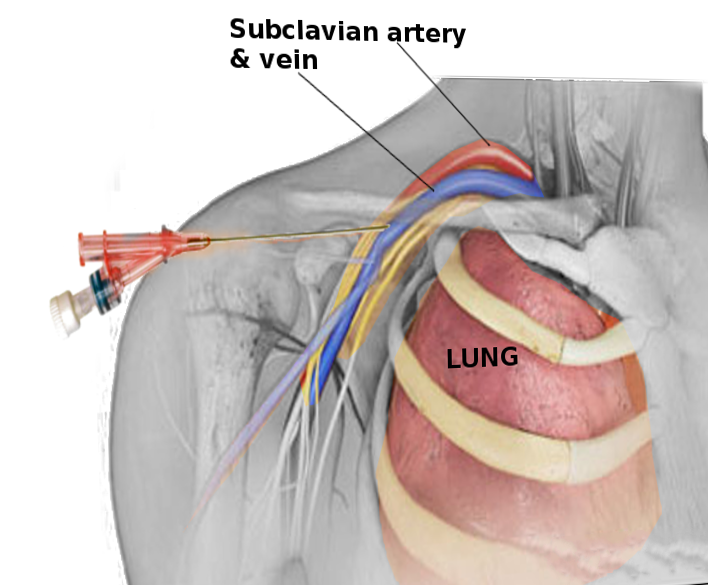

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

In the normal variant of human anatomy, the subclavian vein occurs bilaterally and is a continuation of the axillary vein (a continuation of the brachial vein) from either upper extremity. At the lateral border of the first rib, the axillary vein becomes the subclavian vein where it passes over the rib in the groove of the subclavian vein. Just posterior to the subclavian vein in this area is the axillary artery which becomes the subclavian artery at the lateral border of the first rib and lies in the groove of the subclavian artery. The subclavian vein continues beneath the clavicle heading towards the sternal notch until at the medial border of the anterior scalene muscle it joins the internal jugular vein and becomes the brachiocephalic vein, also called the innominate vein. Also important to note is the pleural apex of the lung which lies inferior to the medial aspect of the subclavian vein. The left side pleural apex often projects more superiorly than the right leading to an increased risk of pneumothorax with left-sided access. The thoracic duct also terminates at the junction of the left subclavian vein and internal jugular vein. This is importantly related to subclavian venous access because it represents another area of potential injury. A potential advantage of left-sided access is the easier sweeping curve of the left innominate vein that leads to the superior vena cava located in the right mediastinum.[4][5]

Indications

Indications for central venous access include:

- Inadequate peripheral venous access

- Administration of medications noxious to peripheral veins (chemotherapy, vasopressors, parental nutrition)

- Advanced hemodynamic monitoring (central venous pressure, venous oxyhemoglobin saturation, cardiac parameters via Swan-Ganz catheter)

- Cardiac access for temporary transvenous pacing

- Hemodialysis

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Contraindications

Contraindications are for the most part relative and include, abnormal anatomy, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, and need for current or future hemodialysis. Although coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia are relative contraindications, it may be prudent to choose a more compressible access site in patients with these conditions. The possible need for current or future hemodialysis access is also a relative contraindication as access to the subclavian vein may affect flow rates needed for hemodialysis (for more distal fistulas or grafts) on that side. A complete assessment of risks versus benefit should be undertaken prior to selection of a site for central venous access.

Equipment

Equipment for subclavian access depends on the type of access necessary. Kits are available for many different needs and include triple lumen central lines, large bore catheters for dialysis, large bore single lumen "trauma" lines, permanent subcutaneous port kits and tunneled catheters. General supplies for all catheter placements include a needle, guide wire, knife, dilators, and the catheter itself. One will also need all supplies to ensure sterile technique throughout the procedure including skin prep, personal protective equipment, sterile draping, and dressings.

There are also differences in catheters themselves. Simple triple lumen catheters can have different sized lumens and can be impregnated with antimicrobial substances to prevent infection. More permanent tunneled catheters often have a cuff that is buried subcutaneously to prevent catheter dislodgement. Subcutaneous ports also have different features, for example, power port capabilities to allow for rapid injection of contrast before CT scanning.

It is important to understand the indication for the central venous catheter placement so that the correct catheter is chosen for the patient's needs.

Preparation

With appropriate preparation, most subclavian venous lines can be placed without assistance; however, in the operating room, a surgical scrub tech is often beneficial.

Before the initial incision or needle stick, excellent skin prep is required to prevent invocation of the catheter with skin flora. This can be completed with either betadine or chlorhexidine solution. It is also important to ensure that all participants in the room are wearing a surgical mask and head cover. The operator should use sterile gown and gloves as well. Before the procedure, the patient is placed in the Trendelenburg position. This promotes venous dilation and can help prevent complications of air embolus. A shoulder roll can also be placed along the patient's superior thoracic spine to aid in the initial access. Caution must be taken, and shoulder roll often omitted, in cases of traumatic injury with suspicion of spine injury. The access site (right or left subclavian vein) is then selected. It is important to note that while the right side has a lower incidence of pneumothorax; it has a higher incidence of catheter malposition. The chest wall is then prepped with surgical prep, in general, it is good practice to prep the entire superior aspect of the chest wall from the top of the shoulders to the nipple line and up the patient's neck to the chin. After the prep is dry, sterile drapes are applied so that only the prepped area is exposed. It is useful to ensure there is enough drape to prevent the guide wire from touching the bedding after it is inserted into the vein. Before inserting the needle, all catheters should be flushed with sterile saline. A procedural "time out" should be undertaken prior to beginning the procedure.

Technique or Treatment

After local anesthesia is injected into the skin at the access site the operator places one hand on top of the clavicle and the other controls the puncture needle. Usually, if the right subclavian vein is selected, the left hand is used to palpate for external landmarks and vice versa for the left side. The index finger is then placed in the sternal notch, and the thumb is placed at the angle of the clavicle, approximately two-thirds of the way lateral from the sternal notch. The puncture needle is then advanced through the skin beneath the thumb and angled toward the sternal notch. A syringe is placed on gentle suction while attempting to cannulate the vein. The thumb is used to help guide the needle below the clavicle between the clavicle and the first rib. It is important to guide the needle along a linear path and avoid a steep angle of the needle related to the clavicle. Adjusting the course of the needle while it is in the tissue can cause damage to underlying tissue and possible tearing of the vessels. Therefore, the needle should be all the way back out to the skin before adjusting the direction. Subclavian vein access is confirmed with a flash of dark red blood, and this should drip in a non-pulsatile fashion after the syringe is removed. After access is obtained, the guidewire is advanced into the vein through the needle. If any resistance is met, the guidewire should be removed, with the needle, to avoid shearing the wire on the bevel of the needle during attempted removal. After the guidewire is successfully inserted, the needle is removed. It is important at all times to keep control of the guidewire so that it does not completely enter the vein. A small skin incision is made at the access site large enough to allow the dilator and catheter to pass. The dilator is then passed over the guidewire, always maintaining at least one hand on the wire. During this process, there is usually some mild resistance as the dilator passes through the wall of the vein. The dilator is then removed over the guidewire, and the catheter is placed over the guidewire. All ports are aspirated and flushed to confirm access. If a permanent port or tunneled catheter is to be created, that can be completed at this time. If only temporary access is required, the catheter is secured to the patient's skin. A sterile dressing should be applied after completion of the procedure.

Complications

Complications of subclavian venous access can often be avoided with proper technique.[6][7][8] It is important to recognize complications that do occur as quickly as possible. Ordering a post-procedure chest x-ray should be standard practice. Complications include-

Immediate Complications

Immediate complications occur either during or immediately following central line insertion. They are classified into cardiac, pulmonary, vascular, and catheter placement complications. [9] These complications result from the mistakes made during the insertion process. Therefore, to reduce these complications, we must address the mistakes and try to rectify them. One such advancement is the use of ultrasound for central line placement which has significantly reduced the immediate complication rates. [10]

Cardiac complications

Cardiac complications are one of the immediate complications which occur during subclavian line placement. Most common is the onset of arrhythmias (premature atrial and ventricular contractions) which occur when guidewire comes in contact with the right atrium. [9]These arrhythmias can be easily managed by slightly removing the guidewire.

Vascular complications

The vascular complications encountered during subclavian line placement are arterial injury, bleeding, venous injury, and hematoma formation. [9] Arterial injuries are more common in femoral vein central lines while they are least common in subclavian vein central lines. [11] Various studies have reported the incidence of arterial puncture to be between 4.2 % to 9.3 %. [12][13] The arterial puncture is recognized by the pulsatile flow of blood from the puncture needle but sometimes it may be difficult to elicit the characteristic flow in patients suffering from shock. [12][13]Though the use of ultrasound has reduced the arterial puncture rate, still sometimes, the central line ends up in the arterial system. Leaving the venous catheter in the artery for a long time can lead to the development of stroke, thrombus in the artery, and subsequent neurological manifestations while instant removal with pressure over the artery may lead to the development of hemorrhage, pseudoaneurysm, or an AV fistula. [9] The risk of hemorrhage is increased in patients taking antiplatelet or anticoagulants. [12] Evidence has shown that while keeping the arterial catheter in place, the primary repair was associated with lesser morbidity and mortality than removing the catheter and applying pressure for a variable time. [14] Central venous catheter placement can also be associated with venous injuries. It includes injury to the vena cava, right atrium, and vessels in the mediastinum. [9] Evidence suggests that 4.7% of all central line placement is associated with hematoma formation. [13] Most of the hematomas are small and limited to the tissue plane at the site of needle puncture but sometimes blood collects in the thorax or mediastinum resulting in hemothorax or hemomediastinum, respectively.

Catheter placement complications

There are many case reports of guidewire and catheter entanglement with the IVC filters which were corrected by taking the help of fluoroscopy. [15] There are also reports of catheter entrapment with sutures during cardiovascular surgery. [16] There are many reports of guidewire being entrapped or lost during line placement which was managed by traction removal, surgical removal, or fluoroscopic guidance. [17][18][19]

Pulmonary complications:

Subclavian line placement may be associated with pneumothorax, chylothorax, pneumomediastinum, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, tracheal injury, and air embolism. [9] Pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum occurs in about one percent of cases.[10][11][13] An increased number of attempts during insertion and a large diameter catheter increases the risk of pneumothorax. Chylothorax occurs due to injury to the lymphatic system. Left-sided subclavian line placement has a high risk of lymphatic injury due to the presence of a thoracic duct on the left side. [9] Recurrent laryngeal nerve injuries during central line placement occur due to accidental trauma to the nerve or due to perineural hematoma formation. [9] Tracheal injuries have also been reported during central line placement. They were mainly due to accidental puncture of the trachea by either finder needle or by the large bore central line needle. [9][20] At last, air embolism which is an uncommon but potentially lethal complication of central line placement. Both the volume of air as well as their rate of entry into the venous circulation determine the effect of venous air embolism. Small air embolism is of little significance but large volume can result in acute right heart failure which can progress to cardiogenic shock, pulmonary edema, and stroke through paradoxical air embolism.

The Delayed Complications

Infection and device dysfunction are the delayed complication of central line placements.

Infections: it can lead to sepsis, shock, and death. It is mainly due to biofilm formation on the catheter with Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus aureus are the most commonly isolated organism. [9][21]

Device dysfunction: dysfunction of components of the central venous catheter can lead to the development of delayed complications like catheter blockade due to fibrin sheath formation, catheter fracture, venous thrombosis, stenosis, and infection. Fibrin sheath formation usually occurs within the first week of central line placement and they usually block the distal opening of the catheter. It is usually managed by fibrinolytic like alteplase and sometimes, line stripping is used when fibrinolytic fail to dissolve the fibrin sheath.[10][22] Catheter fracture is another complication of subclavian line placement when it is used for an extended duration. [9] It can result in life-threatening complications like endocarditis, arrhythmia, cardiac perforation, and sepsis. [20] Early and careful removal of all the parts of the catheter is important to prevent further complications. Another complication that can occur due to using central lines for an extended period is venous thrombosis. Patients generally present with ipsilateral limb edema, erythema, and paresthesia. [9] Venous thrombosis can also lead to the development of superior vena cava syndrome. Its incidence is around 1 in 1000 cases. [23] Subclavian lines have the lowest while femoral lines have the highest rate of thrombosis. [23] Venous stenosis is also the result of using a central line for a longer period. Most of the patients who develop venous stenosis are asymptomatic but if they become symptomatic then they can be treated with stenting. [22]

Clinical Significance

Central venous access is necessary for a variety of situations for both temporary and permanent catheterization. Subclavian access can be a safe and reliable technique to achieve central venous access. Subclavian access is used daily by many practitioners and is a valuable skill for any health care provider.[24]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

IV access is essential in hospitalized patients. When patients do not have peripheral access, central lines are inserted. While the central line is usually inserted by a physician, the management of the line is done by a nurse. Today, most hospitals have a team that just caters to central lines and oversees antiseptic techniques, indications, and complications. The nurse is in a prime position to assess the line for complications like infection, thrombosis or dislodgement and report findings to the clinical team. There are now protocols on central line dressings and how long a line should be left in the central vein. The key is to prevent complications by using an interprofessional approach, as failure to do so may prolong hospital stay and increase morbidity. [25][26](Level V)

Outcomes

Data on outcomes after central line placement indicate that complications are not uncommon. Complication rates ranging from 3-20% have been reported and include hemothorax, pneumothorax, infection and air embolism. Studies show that when the central line is inserted in an aseptic fashion, the risk of infection is low. However, there is a great variance in skills among physicians when it comes to insertion of central lines. Thus, many hospitals have a dedicated team that inserts central lines and monitors them until patient discharge [7][27](Level V)

Media

References

Butt MU, Gurley JC, Bailey AL, Elayi CS. Pericardial Tamponade Caused by Perforation of Marshall Vein During Left Jugular Central Venous Catheterization. The American journal of case reports. 2018 Aug 9:19():932-934. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.909005. Epub 2018 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 30089768]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCriss CN, Claflin J, Ralls MW, Gadepalli SK, Jarboe MD. Obtaining central access in challenging pediatric patients. Pediatric surgery international. 2018 May:34(5):529-533. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4251-3. Epub 2018 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 29582149]

Struck MF, Ewens S, Schummer W, Busch T, Bernhard M, Fakler JKM, Stumpp P, Stehr SN, Josten C, Wrigge H. Central venous catheterization for acute trauma resuscitation: Tip position analysis using routine emergency computed tomography. The journal of vascular access. 2018 Sep:19(5):461-466. doi: 10.1177/1129729818758998. Epub 2018 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 29529967]

Paik P, Arukala SK, Sule AA. Right Site, Wrong Route - Cannulating the Left Internal Jugular Vein. Cureus. 2018 Jan 9:10(1):e2044. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2044. Epub 2018 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 29541565]

Merchaoui Z, Lausten-Thomsen U, Pierre F, Ben Laiba M, Le Saché N, Tissieres P. Supraclavicular Approach to Ultrasound-Guided Brachiocephalic Vein Cannulation in Children and Neonates. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2017:5():211. doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00211. Epub 2017 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 29051889]

Wang H, Chen Y, Liu A, Xiang J, Lin Y, Wen Y, Wu X, Peng J. [Complications analysis of subcutaneous venous access port for chemotherapy in patients with gastrointestinal malignancy]. Zhonghua wei chang wai ke za zhi = Chinese journal of gastrointestinal surgery. 2017 Dec 25:20(12):1393-1398 [PubMed PMID: 29280123]

Shibata W, Sohara M, Wu R, Kobayashi K, Yagi S, Yaguchi K, Iizuka Y, Iwasa M, Nakahata H, Yamaguchi T, Matsumoto H, Okada M, Taniguchi K, Hayashi A, Inazawa S, Inagaki N, Sasaki T, Koh R, Kinoshita H, Nishio M, Ogashiwa T, Ookawara A, Miyajima E, Oba M, Ohge H, Maeda S, Kimura H, Kunisaki R. Incidence and Outcomes of Central Venous Catheter-related Blood Stream Infection in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Routine Clinical Practice Setting. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2017 Nov:23(11):2042-2047. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001230. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29045261]

Akaraborworn O. A review in emergency central venous catheterization. Chinese journal of traumatology = Zhonghua chuang shang za zhi. 2017 Jun:20(3):137-140. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2017.03.003. Epub 2017 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 28552330]

Kornbau C, Lee KC, Hughes GD, Firstenberg MS. Central line complications. International journal of critical illness and injury science. 2015 Jul-Sep:5(3):170-8. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.164940. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26557487]

Bhutta ST, Culp WC. Evaluation and management of central venous access complications. Techniques in vascular and interventional radiology. 2011 Dec:14(4):217-24. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2011.05.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22099014]

McGee DC, Gould MK. Preventing complications of central venous catheterization. The New England journal of medicine. 2003 Mar 20:348(12):1123-33 [PubMed PMID: 12646670]

Bowdle A. Vascular complications of central venous catheter placement: evidence-based methods for prevention and treatment. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2014 Apr:28(2):358-68. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.02.027. Epub 2013 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 24008166]

Vats HS. Complications of catheters: tunneled and nontunneled. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2012 May:19(3):188-94. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.04.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22578679]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePatel AR, Patel AR, Singh S, Singh S, Khawaja I. Central Line Catheters and Associated Complications: A Review. Cureus. 2019 May 22:11(5):e4717. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4717. Epub 2019 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 31355077]

Schelling G, Briegel J, Eichinger K, Raum W, Forst H. Pulmonary artery catheter placement and temporary cardiac pacing in a patient with a persistent left superior vena cava. Intensive care medicine. 1991:17(8):507-8 [PubMed PMID: 1797901]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAndrews RT, Geschwind JF, Savader SJ, Venbrux AC. Entrapment of J-tip guidewires by Venatech and stainless-steel Greenfield vena cava filters during central venous catheter placement: percutaneous management in four patients. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 1998 Sep-Oct:21(5):424-8 [PubMed PMID: 9853151]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang HE, Sweeney TA. Subclavian central venous catheterization complicated by guidewire looping and entrapment. The Journal of emergency medicine. 1999 Jul-Aug:17(4):721-4 [PubMed PMID: 10431965]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSong Y, Messerlian AK, Matevosian R. A potentially hazardous complication during central venous catheterization: lost guidewire retained in the patient. Journal of clinical anesthesia. 2012 May:24(3):221-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.07.003. Epub 2012 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 22495087]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJalwal GK, Rajagopalan V, Bindra A, Rath GP, Goyal K, Kumar A, Gamanagatti S. Percutaneous retrieval of malpositioned, kinked and unraveled guide wire under fluoroscopic guidance during central venous cannulation. Journal of anaesthesiology, clinical pharmacology. 2014 Apr:30(2):267-9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.130061. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24803771]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKonichezky S, Saguib S, Soroker D. Tracheal puncture. A complication of percutaneous internal jugular vein cannulation. Anaesthesia. 1983 Jun:38(6):572-4 [PubMed PMID: 6869717]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEarly TF, Gregory RT, Wheeler JR, Snyder SO Jr, Gayle RG. Increased infection rate in double-lumen versus single-lumen Hickman catheters in cancer patients. Southern medical journal. 1990 Jan:83(1):34-6 [PubMed PMID: 2300831]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKhouzam RN, Soufi MK, Weatherly M. Heparin infusion through a central line misplaced in the carotid artery leading to hemorrhagic stroke. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2013 Sep:45(3):e87-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.12.026. Epub 2013 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 23849360]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKusminsky RE. Complications of central venous catheterization. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2007 Apr:204(4):681-96 [PubMed PMID: 17382229]

Matsushima H, Adachi T, Iwata T, Hamada T, Moriuchi H, Yamashita M, Kitajima T, Okubo H, Eguchi S. Analysis of the Outcomes in Central Venous Access Port Implantation Performed by Residents via the Internal Jugular Vein and Subclavian Vein. Journal of surgical education. 2017 May-Jun:74(3):443-449. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.11.005. Epub 2016 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 27932306]

Acar Y, Tezel O, Salman N, Cevik E, Algaba-Montes M, Oviedo-García A, Patricio-Bordomás M, Mahmoud MZ, Sulieman A, Ali A, Mustafa A, Abdelrahman I, Bahar M, Ali O, Lester Kirchner H, Prosen G, Anzic A, Leeson P, Bahreini M, Rasooli F, Hosseinnejad H, Blecher G, Meek R, Egerton-Warburton D, Ćuti EĆ, Belina S, Vančina T, Kovačević I, Rustemović N, Chang I, Lee JH, Kwak YH, Kim do K, Cheng CY, Pan HY, Kung CT, Ćurčić E, Pritišanac E, Planinc I, Medić MG, Radonić R, Fasina A, Dean AJ, Panebianco NL, Henwood PS, Fochi O, Favarato M, Bonanomi E, Tomić I, Ha Y, Toh H, Harmon E, Chan W, Baston C, Morrison G, Shofer F, Hua A, Kim S, Tsung J, Gunaydin I, Kekec Z, Ay MO, Kim J, Kim J, Choi G, Shim D, Lee JH, Ambrozic J, Prokselj K, Lucovnik M, Simenc GB, Mačiulienė A, Maleckas A, Kriščiukaitis A, Mačiulis V, Macas A, Mohite S, Narancsik Z, Možina H, Nikolić S, Hansel J, Petrovčič R, Mršić U, Orlob S, Lerchbaumer M, Schönegger N, Kaufmann R, Pan CI, Wu CH, Pasquale S, Doniger SJ, Yellin S, Chiricolo G, Potisek M, Drnovšek B, Leskovar B, Robinson K, Kraft C, Moser B, Davis S, Layman S, Sayeed Y, Minardi J, Pasic IS, Dzananovic A, Pasic A, Zubovic SV, Hauptman AG, Brajkovic AV, Babel J, Peklic M, Radonic V, Bielen L, Ming PW, Yezid NH, Mohammed FL, Huda ZA, Ismail WN, Isa WY, Fauzi H, Seeva P, Mazlan MZ. 12th WINFOCUS world congress on ultrasound in emergency and critical care. Critical ultrasound journal. 2016 Sep:8(Suppl 1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13089-016-0046-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27604617]

Hamilton H. Central venous catheters: choosing the most appropriate access route. British journal of nursing (Mark Allen Publishing). 2004 Jul 22-Aug 11:13(14):862-70 [PubMed PMID: 15284651]

Alexandrou E, Spencer TR, Frost SA, Mifflin N, Davidson PM, Hillman KM. Central venous catheter placement by advanced practice nurses demonstrates low procedural complication and infection rates--a report from 13 years of service*. Critical care medicine. 2014 Mar:42(3):536-43. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a667f0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24145843]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence