Introduction

A chalazion is a chronic sterile lipogranuloma. They are typically slowly enlarging and non-tender. A deep chalazion is caused by inflammation of a tarsal meibomian gland. A superficial chalazion is caused by inflammation of a Zeis gland. Chalazia are typically benign and self-limiting, though they can develop chronic complications.[1] Recurrent chalazia should be evaluated for malignancy.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Chalazia are caused by inflammation and obstruction of sebaceous glands of the eyelids. While infection can cause the inflammation or obstruction that leads to a chalazion, the lesion itself is an inflammatory lesion.

Epidemiology

It is a common condition, though the exact incidence in either the US or worldwide is not documented. It appears to affect males and females equally, but exact numbers are not available. Chalazia occur more commonly in adulthood (ages 30-50).

Pathophysiology

Chalazia are inflammatory lesions that form when lipid breakdown products leak into surrounding tissue and incite a granulomatous inflammatory response. For this reason, a chalazion is also called a conjunctival granuloma. Meibomian glands are embedded in the tarsal plate of the eyelids; therefore, edema due blockage of these glands is ordinarily contained to the conjunctival portion of the lid. On occasion, a chalazion may enlarge and break through the tarsal plate to the external portion of the lid. Chalazia due to blockage of Zeis glands are usually located along the lid margin.

Histopathology

Histopathology evaluation is rarely needed in the diagnosis and management of chalazia. If obtained, histologic examination reveals a chronic granulomatous reaction with numerous lipid-filled, Touton-type giant cells. Typically, the nuclei of these cells are located around a central foamy cytoplasmic area that contains the ingested lipid material. Mononuclear cells, including lymphocytes or macrophages, may also be found at the periphery of the lesion as this is an inflammatory process. If a secondary bacterial infection develops, then one could expect to find an acute necrotic reaction with PMNs.[2]

History and Physical

A chalazion usually presents as a painless swelling on the eyelid for weeks or months before the patient seeks medical treatment. Often a chalazion causes impaired vision or discomfort or becomes inflamed, painful, or infected. Frequently, the patient will have a history of previous similar lesions, as chalazia tend to recur in predisposed individuals.

Because chalazion is largely a clinical diagnosis, the chief complaint must be examined thoroughly to exclude other possible diagnoses, requiring a more involved workup. Typical history questions should cover the character of the lesion, the speed of onset, progression of the lesion, aggravating/alleviating factors, associated symptoms, and history of similar lesions. Lesions that recur in a particular location require workup to exclude carcinoma. Travel history is important to obtain as well, particularly patient visits to regions endemic for tuberculosis and leishmaniasis. Case reports have identified these as etiologies mistaken for chalazion.[3][4] Further history should be evaluated for visual changes, recent infections, recent antibiotics, skin infections, trauma to the lid, toxic exposures, immunocompromised status, history of cancer or history of/exposure to tuberculosis. Symptoms point to a diagnosis other than a chalazion include acute visual changes or eye pain that recurs in the same location, fever, extraocular movement limitations, and diffuse eyelid or facial swelling.

Physical findings consistent with chalazion include a palpable, usually non-tender (though in acute inflammation there may be some associated tenderness), non-fluctuant, non-erythematous nodule on the eyelid. The chalazion would be expected to be less than 1 cm in size. It presents more often on the upper lid as a single lesion, though multiple lesions are possible. Chalazia tend to be deeper within the lid than hordeolum. Hordeolum are usually tender, superficial, and centered on an eyelash. The eyelid should be everted as part of the examination to evaluate for an internal chalazion. Visual acuity should be assessed. If there is a pain of the globe, fluorescein staining can evaluate for an associated corneal abrasion.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of a chalazion is usually clinical. If history and examination are consistent, no further workup is required. If there is a question of an alternative diagnosis, a biopsy should be considered.

Treatment / Management

Conservative management is the initial strategy for chalazia.[5] Warm compresses should be applied to the affected lid for 15 minutes 2 to 4 times per day. Lid massage and possibly using baby shampoo on the lids can also be effective. Most chalazia resolve within one month with these conservative measures. If symptoms persist beyond one month, a referral to ophthalmology is recommended. There have been case reports of migration of the lesion with conservative management. [6] If this occurs, referral to ophthalmology for surgical management is suggested. There is potential for larger central lesions to cause complications, so earlier referral for surgical management should be considered in these cases as well. Antibiotics are not routinely needed as this is an inflammatory condition. However, there may be times when an associated infectious etiology is suspected. If an infection is considered, tetracyclines are the antibiotics of choice. Doxycycline 100 mg by mouth twice daily for 10 days or minocycline 50 mg by mouth daily for 10 days would be reasonable options. In patients unable able to take tetracycline, metronidazole is the preferred alternative. If there is no evidence of infection, intralesional steroids could be used. Injection of 0.2 to 2 mL of triamcinolone 40 mg/mL solution would be a typical choice. Larger lesions may require a repeat injection in 2 to 7 days. Persistent lesions require surgical intervention. Smaller lesions may be treated with surgical curettage and dissection. Larger lesions require a more extensive excision. Recurrent chalazia should be biopsied to rule out sebaceous cell carcinoma.

Differential Diagnosis

While less common than chalazion, neoplasms must be considered, particularly in recurrent chalazia in the elderly. Carcinoma such as a sebaceous cell, basal cell, and squamous cell must be ruled out by biopsy if there is a clinical concern. Infectious etiologies such as blepharitis, dacryocystitis, herpes zoster, herpes simplex, molluscum contagiosum, Leishmaniasis, and cellulitis should be considered and treated when appropriate. Benign lesions such as papillomas, hordeolum, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and xanthelasma should be considered if appearance is not typical for chalazia.[7]

Prognosis

Prognosis is excellent for patients with chalazia. There is often resolution with conservative management.[8]

Complications

Untreated chalazia can predispose patients to preseptal cellulitis, which can lead to lid disfiguration with progression. Large central chalazia can cause visual disturbances due to the effects of direct contact with the cornea. Upper lid chalazion increases astigmatism and corneal aberrations, especially at the peripheral cornea. This risk is significantly increased by chalazion greater than 5 mm in size. Therefore excision of these lesions should be considered.[9][10]

Consultations

As discussed above, complicated, large or non-responding chalazia should be evaluated by an ophthalmologist.

Deterrence and Patient Education

There is no specific preventive strategy for avoiding chalazia, although cleaning the eyelids regularly and using warm compresses are thought to have some preventative effects. [11]

Pearls and Other Issues

Remember that chalazia themselves are an inflammatory, not an infectious process. Antibiotics are only indicated if there is evidence of an associated infectious process. The majority of chalazia respond very well to conservative management. Ophthalmology should be consulted for recurrent or refractory chalazia.[5]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Chalazia are often encountered in clinical practice by nurse practitioners, primary care providers, internists, and emergency department physicians. While the majority of these lesions can be managed conservatively, it is important to refer the patient to the ophthalmologist if the lesion is recurrent, infected or causing visual problems. Most healthcare professionals do not have the technical expertise to surgically manage these lesions. The prognosis for chalazion is excellent. Most resolve with conservative treatment.[5][12] (Level V)

Media

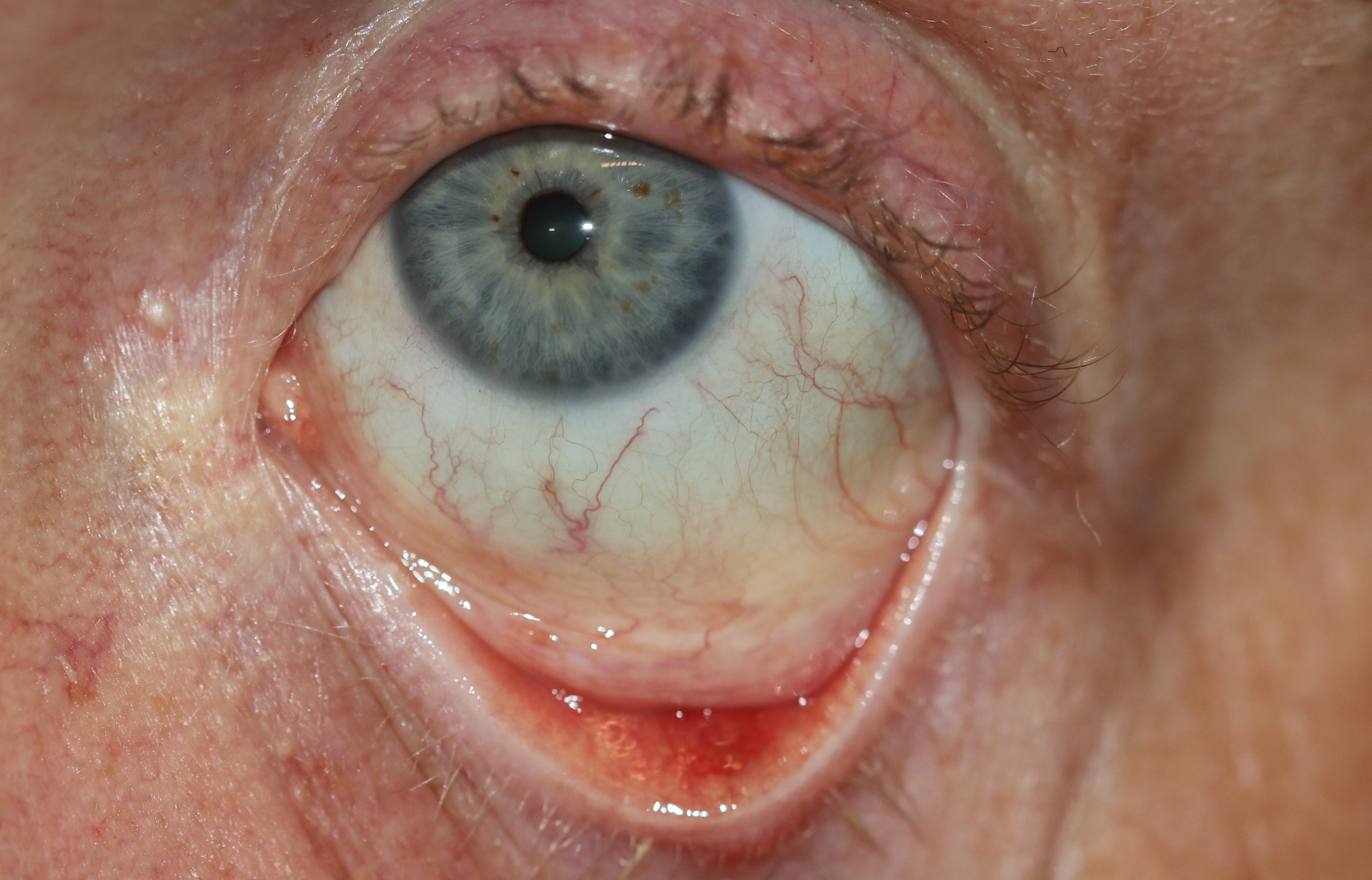

(Click Image to Enlarge)

A 28-year-old male presents with a "bump" that has been there for two weeks and one week before presentation, it drained a mucoid material on the inner side of the lid. The bump was painful but is no longer painful and the bump is smaller. This an example of a left lower eyelid chalazion which has spontaneously drained. These will generally get better with no further treatment needed although physicians will often ask the patient to apply erythromycin eye ointment twice a day to the bump and also apply warm soaks to the eyelid twice a day. Contributed by Prof. Bhupendra C. K. Patel MD, FRCS

References

Jin KW, Shin YJ, Hyon JY. Effects of chalazia on corneal astigmatism : Large-sized chalazia in middle upper eyelids compress the cornea and induce the corneal astigmatism. BMC ophthalmology. 2017 Mar 31:17(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s12886-017-0426-2. Epub 2017 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 28359272]

Fukuoka S, Arita R, Shirakawa R, Morishige N. Changes in meibomian gland morphology and ocular higher-order aberrations in eyes with chalazion. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2017:11():1031-1038. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S133060. Epub 2017 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 28615923]

Mittal R, Tripathy D, Sharma S, Balne PK. Tuberculosis of eyelid presenting as a chalazion. Ophthalmology. 2013 May:120(5):1103.e1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23642745]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHanafi Y, Oubaaz A. [Leishmaniasis of the eyelid masquerading as a chalazion: Case report]. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2018 Jan:41(1):e31-e33. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2017.03.026. Epub 2018 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 29310954]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWu AY, Gervasio KA, Gergoudis KN, Wei C, Oestreicher JH, Harvey JT. Conservative therapy for chalazia: is it really effective? Acta ophthalmologica. 2018 Jun:96(4):e503-e509. doi: 10.1111/aos.13675. Epub 2018 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 29338124]

Chang M, Park J, Kyung SE. Extratarsal presentation of chalazion. International ophthalmology. 2017 Dec:37(6):1365-1367. doi: 10.1007/s10792-016-0409-y. Epub 2016 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 27942990]

Carlisle RT, Digiovanni J. Differential Diagnosis of the Swollen Red Eyelid. American family physician. 2015 Jul 15:92(2):106-12 [PubMed PMID: 26176369]

Ozer PA, Gurkan A, Kurtul BE, Kabatas EU, Beken S. Comparative Clinical Outcomes of Pediatric Patients Presenting With Eyelid Nodules of Idiopathic Facial Aseptic Granuloma, Hordeola, and Chalazia. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2016 Jul 1:53(4):206-11. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20160511-03. Epub 2016 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 27182747]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAycinena AR, Achiron A, Paul M, Burgansky-Eliash Z. Incision and Curettage Versus Steroid Injection for the Treatment of Chalazia: A Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2016 May-Jun:32(3):220-4. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000483. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26035035]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePark YM, Lee JS. The effects of chalazion excision on corneal surface aberrations. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association. 2014 Oct:37(5):342-5. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2014.05.002. Epub 2014 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 24890201]

Arbabi EM, Kelly RJ, Carrim ZI. Chalazion. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2010 Aug 10:341():c4044. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4044. Epub 2010 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 21155069]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGörsch I, Loth C, Haritoglou C. [Chalazion - diagnosis and therapy]. MMW Fortschritte der Medizin. 2016 Jun 23:158(12):52-5. doi: 10.1007/s15006-016-8447-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27324006]