Introduction

A chordoma is a low-grade, slow-growing, but locally invasive and locally aggressive tumor. Chordomas belong to the sarcoma family of tumors. They arise from the remnants of the notochord and occur in the midline along the spinal axis from the clivus to the sacrum, anterior to the spinal cord. The location distribution of chordomas is 50% sacral, 35% skull base, and 15% occur in the vertebral bodies of the mobile spine (most commonly the C2 vertebrae followed by the lumbar then thoracic spine). Overall 5-year survival is approximately 50%, and treatment is en bloc surgical resection followed by high-dose conformal radiation therapy such as proton beam radiation.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Chordomas arise from the notochord. The notochord is the mesodermal structure in the embryo, which serves to help signal tissues for organization and differentiation. The notochord ultimately becomes the nucleus pulposus in humans as it regresses. Genes implicated in chordoma formation include the brachyury gene, mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signing pathway, phosphatase, and tensin homolog (PTEN) gene deficiency, INI-1 and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFR-beta) although no definitive genetic marker has as of yet been identified.[3] There are currently a few reported familial clusters of chordomas.

Epidemiology

Chordomas typically affect those in the 40-60-year-old age group but have been reported in children and the very elderly. Most believe males are more commonly affected than females in an approximately 2:1 ratio with an annual incidence of 1:1,000,000 for new diagnoses. Chordomas account for approximately 20% of primary spinal tumors and only 3% of all bone tumors. The most common location is in the sacrum/coccygeal region (50%), followed by 35% located in the spheno-occipital region, and the remaining chordomas (about 10% to 15%) located in the mobile spine. [2]

Pathophysiology

Chordomas present with slow-growing, locally invasive tumors with distant metastases are rarely occurring and only late in the disease. Although they are considered indolent tumors, there is a significant risk for multiple recurrences locally.

History and Physical

The patient history and physical findings are dependent on the specific location of the chordoma. Skull base and clival chordomas typically present with headaches and or cranial nerve dysfunctions, most often cranial nerve VI (abducens nerve), although the lower cranial nerves can also be affected. Rarely a clival chordoma will present with rhinorrhea due to a cerebrospinal fluid leak. Cervical chordomas typically present with non-specific neck, shoulder or arm pain, and occasionally dysphagia due to mass effect. Cervical chordomas can also invade cranially to cause lower cranial nerve dysfunction as well as compression of the spinal cord or exiting nerves causing myelopathy or radiculopathy, respectively. Thoracic and lumbar chordomas also present with non-specific localized pain and, also, may be the cause of a pathologic fracture or radiculopathy or myelopathy. Sacral chordomas share a similar presentation as thoracic and lumbar chordomas with localized pain and possible radiculopathy as well as possible dysfunction of the bladder, bowel, or autonomic nervous system if the tumor involves the lumbosacral plexus.

Evaluation

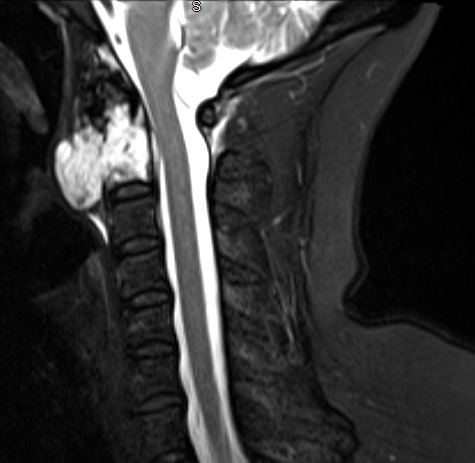

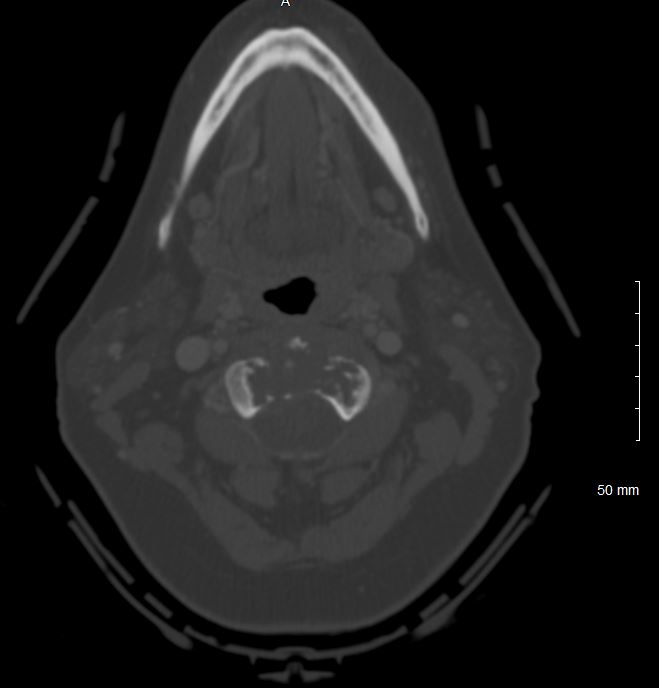

Evaluation of chordomas revolves around imaging and biopsy. A plan x-ray will demonstrate a locally destructive lytic lesion. Computed tomography (CT) imaging is better for demonstrating the destructive lytic chordoma. Occasionally the chordoma will have sclerosis at the margin. Chordomas are hypodense compared to bones on CT and may demonstrate irregular dystrophic calcification. Chordomas demonstrate moderate to significant enhancement in contrasted CT imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) best delineates the extent of a chordoma. Chordomas have lower signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging and may show foci of hyperintensity, which represents intratumoral hemorrhage. T1-weighted imaging with gadolinium contrast demonstrates heterogeneous contrast enhancement of the tumor with a honeycomb appearance. On T2-weighed imaging, chordomas tend to be hyperintense. Gradient-echo MRI imaging can confirm intratumoral hemorrhage. Bone scans are sometimes obtained during the workup, and chordomas have normal to decreased uptake.

Many times a needle or open biopsy is performed to confirm the diagnosis of chordoma. Care needs to be taken when planing and performing the biopsy as the chordoma can seed along the biopsy tract. Thus the biopsy tract should be included in the future chordoma resection to decrease the risk of local recurrence.

Treatment / Management

The treatment which provides the longest survival is complete en bloc resection of the tumor with clean margins. This can prove to be challenging either due to the location of the chordoma or reconstructive needs after resection. Intratumoral resection and piecemeal resection may also provide a similar benefit if complete chordoma resection can be achieved without local seeding. Local debulking is sometimes advocated if complete resection is not technically feasible. Local debulking can alleviate symptoms secondary to mass effect as well as provide a smaller target volume for future radiation therapy.

Most physicians advocate for radiation therapy after any type of chordoma resection due to the high local recurrence rate. Chordomas are relatively radioresistant, necessitating high-dose radiation therapy. As chordomas are found near neuronal structures, highly-conformal radiotherapy is used, including proton beam radiation or radiosurgery. Conventional photon radiation is currently thought to be of no benefit to chordoma patients.

The slow-growing nature of chordomas makes them resistant to most current conventional chemotherapeutic agents. If a chordoma is treated with chemotherapy, then treatment typically occurs within a clinical trial.

Due to the high local recurrence of chordomas, most physicians recommend lifelong surveillance with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without gadolinium contrast. Metastatic chordoma should be on the differential if new lesions arise elsewhere in the body as up to 20% of chordomas can metastasize.[4]

Differential Diagnosis

Clival/Spheno-occipital lesions:

- Benign notochordal cell tumor

- Chondrosarcoma

- Ecchordosis physaliphora

- Meningioma

- Pituitary macroadenoma

- Plasmacytoma

Vertebral lesions:

- Chondrosarcoma

- Giant cell tumor

- Plasmacytoma

- Spinal metastases

- Spinal lymphoma

Pearls and Other Issues

It should be stressed that if chordoma is entertained in the differential diagnosis, there should be careful planning of any biopsy as the biopsy tract needs to be included in the ultimate resection of the chordoma to decrease the risk of local recurrence.

Despite the low-grade status of chordomas, they have a high recurrence rate and significant mortality. Five-year survival is approximately 50% overall but improved with complete resection with negative margins to a 65% 5-year survival rate. Surgical resection with positive margins is approximately 50% 5-year survival, and if the chordoma is inoperable 5-year survival is approximately 40%.

Macroscopically chordomas are soft, gelatinous tumors and may have hemorrhage present. Microscopically they consist of fibrous septa separating lobules of physaliferous (bubbly) cells with an extensive myxoid stroma and rare mitotic figures.

Chordomas can be divided into four subtypes: conventional, poorly differentiated, dedifferentiated, and chondroid. Conventional (classic) chordomas are the most common variety and may show areas of dedifferentiation. Poorly differentiated chordomas are more common in young adult and pediatric patients as well as skull base chordomas. Poorly differentiated chordomas show a loss of the gene INI-1. Dedifferentiated chordomas typically are the fastest growing and most aggressive chordomas and can also have a loss of INI-1 and are more common in pediatric patients. Chondroid chordoma describes chordomas that are difficult to distinguish from chondrosarcoma on histology. Typically chordomas express the gene brachyury, whereas chondrosarcomas do not express the brachyury gene.

Chordomas have been reported to dedifferentiate into high-grade spindle cell tumors, which portend a worse prognosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of chordoma is best done with an interprofessional team that includes an orthopedic surgeon, radiologist, neurologist, and pathologist. Depending on the location, other specialists may be involved like the neurosurgeon, oncology nurse, pediatrician, and ENT surgeon. Chordomas are locally aggressive tumors and wide en bloc resection is the ideal treatment. Nurses are involved in perioperative care, recovery, and rehabilitation. They monitor patient status, educate patients and their families, and update the rest of the team. Pharmacists review medications, check for drug-drug interactions and provide education too. Oncology specialty pharmacists can assist with clinical trial selection if chemotherapy is considered. Recurrences are common and in some cases, the tumor may degenerate into aggressive cancer. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Young VA, Curtis KM, Temple HT, Eismont FJ, DeLaney TF, Hornicek FJ. Characteristics and Patterns of Metastatic Disease from Chordoma. Sarcoma. 2015:2015():517657. doi: 10.1155/2015/517657. Epub 2015 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 26843835]

George B, Bresson D, Herman P, Froelich S. Chordomas: A Review. Neurosurgery clinics of North America. 2015 Jul:26(3):437-52. doi: 10.1016/j.nec.2015.03.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26141362]

Gulluoglu S, Turksoy O, Kuskucu A, Ture U, Bayrak OF. The molecular aspects of chordoma. Neurosurgical review. 2016 Apr:39(2):185-96; discussion 196. doi: 10.1007/s10143-015-0663-x. Epub 2015 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 26363792]

Heery CR. Chordoma: The Quest for Better Treatment Options. Oncology and therapy. 2016:4(1):35-51. doi: 10.1007/s40487-016-0016-0. Epub 2016 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 28261639]