Introduction

Gestational trophoblastic diseases were first described in 400 BC by Hippocrates.[1] Choriocarcinoma, a subtype of gestational trophoblastic disease,[2] is a rare and aggressive neoplasm.[3] The 2 significant choriocarcinoma subtypes, namely: gestational and non-gestational, have very different biological activity and prognoses. Choriocarcinoma predominately occurs in women but can also occur in men, usually as part of a mixed germ cell tumor.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Choriocarcinoma develops from an abnormal trophoblastic population undergoing hyperplasia and anaplasia, most frequently following a molar pregnancy.[3] There are 2 forms of choriocarcinoma, gestational and non-gestational. The former arises following a hydatidiform mole, normal pregnancy, or most commonly, spontaneous abortion, while non-gestational choriocarcinoma arises from pluripotent germ cells.[4] Non-gestational choriocarcinomas form in males or females, in the gonads, or midline structures with pluripotent germ cells.[4]

Epidemiology

Choriocarcinoma is a very rare neoplasm with varied incidence worldwide.[3] In Europe and North America, about 1 in 40,000 pregnant patients and 1 in 40 patients with hydatidiform moles will develop choriocarcinoma.[3][5] In Southeast Asia and Japan, 9.2 in 40,000 pregnant women and 3.3 in 40 patients with hydatidiform moles will subsequently develop choriocarcinoma.[3] In China, 1 in 2882 pregnant women will develop choriocarcinoma.[5] This correlates with an increased risk for the development of choriocarcinoma in Asian, American Indian, and African American women.[3] Other risk factors include prior complete hydatidiform mole (a 100-fold increased risk), advanced age, long-term oral contraceptive use, and blood type A.[3]

Choriocarcinoma composes less than 0.1% of primary ovarian neoplasms in a pure form.[6]

Choriocarcinoma can also occur in males, usually those between ages 20 to 30.[7] Less than 1% of testicular tumors are pure choriocarcinoma.[6][7] Mixed germ cell tumors occur much more frequently in the testicle, with choriocarcinoma as a component in 15% of these tumors.[7]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathogenesis of choriocarcinoma has not been fully explained or understood, but studies have shown cytotrophoblastic cells function as stem cells and undergo malignant transformation. The neoplastic cytotrophoblast further differentiates into intermediate trophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblast.[8] The mixture of cells mimics the normal development of a previllous blastocyst, a feature seen in other gestational trophoblastic neoplasms.[9]

Overexpression of p53 and MDM2 have been demonstrated in choriocarcinoma, with no evidence of somatic mutation. Other genes implicated with either overexpression or down-regulation via hyper-methylation include NECC1, epidermal growth factor receptor, DOC-2/hDab2, Ras GTPase-activating protein, E-cadherin, HIC-1, p16, and TIMP3. HLA-G is demonstrated at very high levels in choriocarcinoma and functions to change the tumor microenvironment through the inactivation of the local immune system.[9]

Histopathology

Syncytiotrophoblasts, large eosinophilic smudgy multinucleated cells with known, large hyperchromatic nuclei, are intermixed with cytotrophoblasts, polygonal cells with distinct borders, and single irregular nuclei.[7] Additionally, choriocarcinoma is an extremely vascular carcinoma characterized by necrosis and the absence of chorionic villi.[3]

Following chemotherapy, the cytotrophoblasts may predominate, making the diagnosis more difficult. Within the uterus, choriocarcinoma invades vessels to spread throughout the body, a relatively early finding.[3]

Intra-placental choriocarcinoma demonstrates trophoblast proliferation around villi in a third-trimester placenta, usually otherwise normal in appearance.[10][11]

In mixed germ cell tumors, choriocarcinoma will also have a mixture of syncytiotrophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts and varying components of other germ cell tumors.

History and Physical

The healthcare professional should conduct a thorough history and physical examination of any patient with suspected choriocarcinoma. In women, clinicians should pay particular attention to reproductive history because spontaneous abortions and molar pregnancies increase the risk for choriocarcinoma. One should consider post-menopausal bleeding suspicious. Choriocarcinoma tends to metastasize, and clinicians should note symptoms that arise from other organ systems, for example, hemoptysis or gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.[5]

Due to elevations in human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels, patients can present with abnormal uterine bleeding, gynecomastia (in men), or hyperthyroidism.[6]

Males will present can present with symptoms of metastatic disease, often hemoptysis, but the liver, GI tract, and brain are also frequently involved.[7]

Evaluation

Many laboratory tests can assess for choriocarcinoma, including complete blood count (CBC), coagulation studies, body chemistries, renal function panels, liver function panels, type and screen, and quantitative hCG.[12]

The United Kingdom registers and monitors all patients with hydatidiform or molar pregnancies and utilizes the following criteria to start chemotherapy for gestational trophoblastic disease:[1]

- Plateaued or rising hCG following uterine evacuation

- Heavy vaginal bleeding

- Gastrointestinal or intraperitoneal bleeding

- Histologic evidence of choriocarcinoma

- Evidence of metastases in brain, liver, or gastrointestinal tract

- Lung opacities greater than 2 cm

- Serum hCG greater than 20,000 IU/L 4 weeks following evacuation

- Elevated hCG greater than 6 months after evacuation even when decreasing

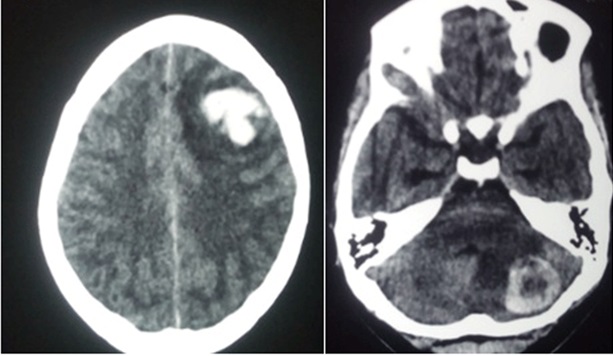

Following the diagnosis of choriocarcinoma, the healthcare professional should evaluate patients for metastasis; the lungs are the most common site for metastasis.[5] Chest, abdomen, and pelvic computed tomography are recommended in staging due to the highly metastatic nature of choriocarcinoma. Evaluate the brain via computer tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[12] See Image. Choriocarcinoma Metastasis to Brain.

In males who have developed choriocarcinoma, the testicular anatomy is usually very small or even regressed, leaving only metastatic disease and cells.[7]

Treatment / Management

A low-risk (cumulative score less than 7, see staging section below) and stage I to III choriocarcinoma can be treated with a single agent, either methotrexate or actinomycin D chemotherapy.

High-risk (a cumulative score greater than 7, see staging section below) and stage II to IV disease are treated with multi-agent chemotherapy, adjuvant radiation, and surgery.[12]

Following treatment and hCG normalization, quantitative hCG levels should be checked monthly for one year with a physical exam twice in the same time frame. If a subsequent pregnancy occurs, first-trimester pelvic ultrasound should be performed to confirm uterine location due to the small but present risk of recurrent choriocarcinoma; the placenta should be submitted for histologic examination of recurrence.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes:[3][7]

- Placental site trophoblastic tumor

- Seminoma

- Mixed germ cell tumor

- Solid variant of yolk sac tumor

- Embryonal carcinoma

Surgical Oncology

Surgical resection of either the uterus or metastatic foci is utilized in conjunction with chemotherapy in approximately half of the patients with high-risk choriocarcinoma.[12]

Radiation Oncology

The use of 3000 cGy, given in 200 cGy fractions, is done for whole-brain irradiation of central nervous system (CNS) metastases.[12]

Medical Oncology

In the United States, low-risk (cumulative score less than 7, refer to staging section below) and stage I to III choriocarcinoma is treated with either methotrexate or actinomycin D chemotherapy with survival rates approaching 100%.

In the United States and the United Kingdom, multi-agent chemotherapy with etoposide, actinomycin D, methotrexate, folinic acid, cyclophosphamide, and vincristine are utilized as first-line treatment for patients with high-risk choriocarcinoma.[1][12]

In the United Kingdom, gestational choriocarcinoma is usually treated with a combination of etoposide, methotrexate, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide, and vincristine.[1] If the patient has a large tumor load, induction therapy with etoposide and cisplatin has shown good results.[4]

Staging

The World Health Organization and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics developed the following staging system for choriocarcinoma:[1][12]

- Stage I: Disease confined to the uterus

- Stage II: Disease extending beyond the uterus, but confined to genital structures

- Stage III: Disease extending to the lungs

- Stage IV: Disease invading other metastatic sites

Criteria

Furthermore, the patients are then stratified into low- and high-risk groups to determine treatment based on the following criteria:

Age

- 0: Younger than 39 years old

- 1: Greater than 39 years old

Antecedent Pregnancy

- 0: Mole

- 1: Abortion

- 2: Term

Pregnancy Event to Treatment Interval

- 0: Less than 4 months

- 1: 4 to 6 months

- 2: 7 to 12 months

- 4: Greater than 1 year

Pretreatment hCG (mIU/ml)

- 0: Less than 10^3

- 1: 10^3 to 10^4

- 2: 10^4 to 10^5

- 4: Greater than 10^5

Largest Tumor Mass

- 0: Less than 3 cm

- 1: 3 to 4 cm

- 2: Greater than 5 cm

Site of Metastases

- 0: None

- 1: Spleen, kidney

- 2: GI tract

- 4: Brain, liver

Number of Metastases

- 0: None

- 1: 1 to 4

- 2: 5 to 8

- 4: Greater than 8

Previous Failed Chemotherapy

- 0: None

- 2: Single-drug

- 4: Greater than 2 drugs

Cumulative Score

- Low-risk: Less than 7

- High-risk: Greater than 7

Prognosis

Gestational choriocarcinoma and non-gestational choriocarcinoma have different prognoses, with non-gestational choriocarcinoma having a much worse prognosis.[4][13] The latter is also much less chemosensitive. Genotyping highlights the difference in gestational and non-gestational choriocarcinoma; gestational choriocarcinoma usually has a paternal chromosome complement while non-gestational choriocarcinoma has DNA that matches the patient, with occasional karyotype abnormalities.[13]

Low-risk gestational choriocarcinoma has almost 100% survival in women treated with chemotherapy, and high-risk gestational choriocarcinoma patients have 91% to 93% survival when utilizing multi-agent chemotherapy with or without radiation and surgery. Adverse risk factors making death more likely include stage IV disease or a cumulative score greater than 12 in women.[12]

In men with mixed germ cell tumors, increasing amounts of choriocarcinoma portend a worse prognosis, with pure choriocarcinomas having the worst prognosis in testicular germ cell neoplasms. An hCG greater than 50,000 mIU/ml also correlates to a worse prognosis in men.[7]

Intra-placental choriocarcinoma with metastasis to the infant carries a very poor prognosis, with less than 20% survival.[10]

Complications

Without treatment, choriocarcinoma can result in death. With the advent of chemotherapy, many patients can achieve remission and cure of their disease. The utilization of chemotherapy is not without its risks, including the development of secondary malignancies, nausea, vomiting, hair loss, diarrhea, fevers, infections, and the need for transfusion of blood productions.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Women who experience a molar pregnancy, whether complete or incomplete, should be counseled as to the risk for the development of choriocarcinoma. These patients should be monitored closely for resolution of their hCG levels. Any woman who has given birth, but particularly if she is a high risk, should be counseled to return for continued post-partum bleeding.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Elevated hCG levels in a woman without confirmed intrauterine pregnancy should prompt a search for both ectopic pregnancy and the possibility of a malignancy secreting hCG. Lack of response to methotrexate makes a malignancy much more likely.[14]

- False-positive elevations in hCG can be due to heterophile (human anti-mouse) antibodies and should be considered before treating patients surgically or with systemic chemotherapy.[3]

- In men, choriocarcinoma usually occurs as part of a mixed germ cell tumor; when occurring in a pure form, the primary tumor may be very small or even regressed while symptoms are all related to metastasis.[7]

- Intra-placental choriocarcinoma is a very rare variant usually, presenting with metastatic symptoms in the post-partum mother, and rarely with metastasis in the infant, and should be included on the differential diagnosis of elevated AFP in a postpartum patient.[10]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Clinicians taking care of patients following molar pregnancy should remain aware and vigilant of the pitfall of heterophile (human anti-mouse) antibodies occurring in 3% to 4% of patients, resulting in falsely positive elevated hCG. The presence of heterophile antibodies can be teased out by serial dilution of serum, which will not show a parallel decrease with dilution or sending of serum and patient urine to a reference hCG laboratory.[3]

High clinical suspicion should be maintained for choriocarcinoma in women with hemoptysis and molar pregnancy, current, or recent pregnancy, or irregular vaginal bleeding.[5] An interprofessional treatment center with nurses and clinicians specializing in gestational trophoblastic disease is beneficial to improving outcomes. [Level 1 and 2]

Media

References

Seckl MJ, Sebire NJ, Berkowitz RS. Gestational trophoblastic disease. Lancet (London, England). 2010 Aug 28:376(9742):717-29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60280-2. Epub 2010 Jul 29 [PubMed PMID: 20673583]

Bruce S, Sorosky J. Gestational Trophoblastic Disease. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261918]

Lurain JR. Gestational trophoblastic disease I: epidemiology, pathology, clinical presentation and diagnosis of gestational trophoblastic disease, and management of hydatidiform mole. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010 Dec:203(6):531-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.073. Epub 2010 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 20728069]

Stockton L, Green E, Kaur B, De Winton E. Non-Gestational Choriocarcinoma with Widespread Metastases Presenting with Type 1 Respiratory Failure in a 39-Year-Old Female: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case reports in oncology. 2018 Jan-Apr:11(1):151-158. doi: 10.1159/000486639. Epub 2018 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 29681814]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZhang W, Liu B, Wu J, Sun B. Hemoptysis as primary manifestation in three women with choriocarcinoma with pulmonary metastasis: a case series. Journal of medical case reports. 2017 Apr 16:11(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s13256-017-1256-9. Epub 2017 Apr 16 [PubMed PMID: 28411623]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceUlbright TM. Germ cell tumors of the gonads: a selective review emphasizing problems in differential diagnosis, newly appreciated, and controversial issues. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2005 Feb:18 Suppl 2():S61-79 [PubMed PMID: 15761467]

Ali TZ, Parwani AV. Benign and Malignant Neoplasms of the Testis and Paratesticular Tissue. Surgical pathology clinics. 2009 Mar:2(1):61-159. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2008.08.007. Epub 2009 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 26838100]

Mao TL, Kurman RJ, Huang CC, Lin MC, Shih IeM. Immunohistochemistry of choriocarcinoma: an aid in differential diagnosis and in elucidating pathogenesis. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2007 Nov:31(11):1726-32 [PubMed PMID: 18059230]

Shih IeM. Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia--pathogenesis and potential therapeutic targets. The Lancet. Oncology. 2007 Jul:8(7):642-50 [PubMed PMID: 17613426]

Liu J, Guo L. Intraplacental choriocarcinoma in a term placenta with both maternal and infantile metastases: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecologic oncology. 2006 Dec:103(3):1147-51 [PubMed PMID: 17005243]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHeller DS. Update on the pathology of gestational trophoblastic disease. APMIS : acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica. 2018 Jul:126(7):647-654. doi: 10.1111/apm.12786. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30129126]

Lurain JR. Gestational trophoblastic disease II: classification and management of gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2011 Jan:204(1):11-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.072. Epub 2010 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 20739008]

Savage J, Adams E, Veras E, Murphy KM, Ronnett BM. Choriocarcinoma in Women: Analysis of a Case Series With Genotyping. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2017 Dec:41(12):1593-1606. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000937. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28877059]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLarish A, Kumar A, Kerr S, Langstraat C. Primary Gastric Choriocarcinoma Presenting as a Pregnancy of Unknown Location. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2017 Feb:129(2):281-284. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001808. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28079767]