Introduction

Choroid plexus papillomas are rare central nervous system tumors, comprising less than 1% of all brain tumors. Although choroid plexus papillomas may occur at any age, 70% of patients with this neoplasm are less than 2 years of age.[1] Choroid plexus papillomas are neuroepithelial tumors that are World Health Organization grade I or II. In contrast, the rarely encountered choroid plexus carcinoma is classified as World Health Organization grade III.[2] Choroid plexus papillomas are more common in the infratentorial compartment in adults and the supratentorial compartment in children. Patients with choroid plexus papillomas often present with communicating hydrocephalus secondary to cerebrospinal fluid overproduction. The prognosis of these benign neoplasms is favorable, and gross total resection is frequently curative.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of choroid plexus papillomas is undetermined. Neonatal choroid plexus papillomas are thought to be congenital.[3] Some studies have demonstrated an association between simian virus 40 (SV40) and the occurrence of choroid plexus tumors.[4] BK virus and John Cunningham (JC) viruses have also been implicated.[5] Complexes of SV40 large T antigen and TP53 and Rb proteins have been identified in humans with choroid plexus tumors.[5] The R248W mutation of TP53 is one of the most common mutations in choroid plexus tumors, but current data do not support a causative role.[6]

Epidemiology

Choroid plexus tumors are rare tumors of neuroectodermal origin. In the pediatric population, they are the third-most common congenital brain tumor, after teratomas and gliomas, comprising 0.4% to 0.6% of all intracranial neoplasms.[7] Adults may develop choroid plexus tumors, but the neoplasm is generally a disease of childhood; the median age at diagnosis is 3.5 years, and 70% of patients are less than 2 years of age at the time of diagnosis.[1] In infants, these neoplasms are typically supratentorial within the left lateral ventricles, most commonly the atrium.[8] In contrast, adult choroid plexus papillomas are usually infratentorial in the fourth ventricle and rarely at the cerebellopontine angle.[9]

Some choroid plexus tumors occur in association with specific syndromes, including Aicardi syndrome, hypomelanosis of Ito, chromosome 9p duplication, and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome.[10]

Histopathology

The World Health Organization classifies choroid plexus tumors as papillomas (grade I), atypical tumors (grade II), or carcinomas (grade III).[11] Grossly, the tumors are soft, globular, friable pink masses with irregular projections and high vascularity.

Choroid Plexus Papilloma

Histologically, choroid plexus papillomas have a benign architecture with papillary fronds lined by bland columnar epithelium, resembling the normal choroid plexus. Mitotic activity, nuclear pleomorphism, and necrosis are typically absent.[12] Immunohistochemistry staining is typically positive for cytokeratin, vimentin, podoplanin, and S-100 protein.[13][12] Glial fibrillary acidic protein may be positive in up to 20% of choroid plexus papillomas.[14] Studies have shown that patients 20 years and older express more GFAP and transthyretin than younger patients, and fourth ventricle tumors express more S-100 protein than lateral ventricle tumors.[15]

Genetic analyses have reported germline mutations in TP53 in some patients with choroid plexus papilloma.[16] These tumors rarely show positive nuclear staining for TP53.

Atypical Choroid Plexus Papilloma

The presence of more than 2 mitoses per high-power field is indicative of atypical CPP.

Choroid Plexus Carcinoma

The presence of 4 or more of the following malignant histopathological characteristics is indicative of choroid plexus carcinoma:

- Brisk mitotic activity (> 5 mitoses per 10 high-power fields)

- Nuclear pleomorphism

- High cellularity

- Blurring of the papillary growth pattern

- Necrosis.

DNA Methylation Profiling

DNA methylation profiling of choroid plexus tumors has revealed 3 distinct molecular subgroups or clusters that may provide prognostic information beyond that traditionally provided by routine histopathological identification.[17] Cluster 1 comprises supratentorial pediatric low-risk choroid plexus tumors, including benign papillomas and atypical tumors. Cluster 2 comprises infratentorial adult low-risk choroid plexus papillomas and atypical tumors. Cluster 3 comprises supratentorial pediatric high-risk choroid plexus tumors, including papilloma, atypical tumors, and carcinomas.[17]

History and Physical

Most patients with choroid plexus papillomas present with signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure secondary to hydrocephalus.[18] These symptoms may include headache, nausea with or without vomiting, fussiness, lethargy, and craniomegaly. Depending on the location of the lesion, patients may present with meningismus secondary to subarachnoid hemorrhage, seizures, and focal neurologic deficits characterized by sensory deficits, hemiparesis, cranial nerve palsies, or cerebellar signs.

Hydrocephalus may occur as a result of direct mechanical obstruction to the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) due to an arachnoid granulation blockage from hemorrhage or from CSF overproduction.[19] Choroid plexus papillomas may exhibit rapid growth despite their benign nature.[20] In some patients, CSF rhinorrhea or hemifacial spasms may be the only clinical abnormalities.[21][22]

Evaluation

Diagnostic imaging is indicated in patients with the signs and symptoms of hydrocephalus or those suggestive of an intracranial mass. If the fontanelles are not fused, ultrasonography via the anterior fontanelle may demonstrate an echogenic lesion within the ventricles. This lesion will demonstrate bidirectional flow throughout diastole, indicating blood flow through chaotically arranged vessels. Some lesions have been diagnosed antenatally via ultrasonography.[23]

Computed tomography (CT) may reveal an isodense or slightly hyperdense lesion within the ventricles and consequent ventriculomegaly.[24] Hydrocephalus is typical. Approximately 25% of patients with a choroid plexus papilloma demonstrate speckled intralesional calcifications. The lesions are typically lobulated with slightly irregular margins and intense, somewhat heterogeneous contrast enhancement. Angiographic and cross-sectional imaging frequently demonstrate enlargement of the choroidal artery.

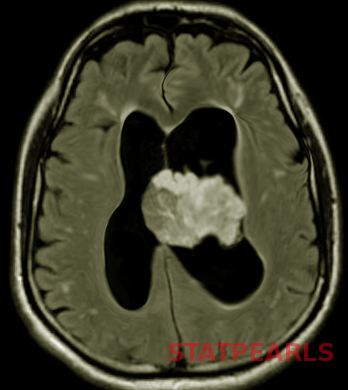

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of choroid plexus papillomas usually demonstrates well-defined, frond-like intraventricular lobulated masses that are hypointense on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences.[25] Flow voids indicative of active blood flow are typical, and this rich vascularity promotes avid enhancement. Arterial spin labeling may help distinguish choroid plexus papilloma from carcinoma.[26] A prominent blush with enlarged choroidal arteries can be visualized on digital subtraction angiography.[2]

Treatment / Management

There is controversy regarding the timing of surgical intervention for incidentally detected choroid plexus papillomas.[27] Prompt surgical resection is one option. However, surgery may be delayed until the patient becomes symptomatic or follow-up imaging demonstrates radiographic tumor progression or hydrocephalus. Tumor resection is facilitated by hydrocephalus; the length of the cortical corridor to the ventricles reduces, and space around the tumor increases. The disadvantage of delayed intervention is the interim development of focal deficits from mass effect, cognitive deficits, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or seizures.[28]

Gross total resection of these benign tumors is the treatment of choice in symptomatic patients. Recent advances in radiographic imaging, surgical approaches, operating microscopy, and quality of intensive care have improved surgical outcomes; long-term cure rates approach 100%.[8] Unfortunately, the pediatric perioperative mortality is 12%; choroid plexus neoplasms are highly vascular, and catastrophic hemorrhage is problematic.[29] Preoperative tumor embolization can minimize this risk and optimize complete resection of the tumor.[30] Percutaneous stereotactic intratumoral embolization with a sclerosing agent has been reported.[31] Radiosurgery may be a possible treatment option; further studies are required.[32](B2)

Postoperative subdural collections may occur following transcortical tumor excision, occasionally resulting from a persistent ventriculosubdural fistula; subdural-peritoneal shunt placement may be required.[1] Although limited in use, adjuvant chemotherapy can prevent recurrence and prolong survival.[33] Expanding residual choroid plexus papillomas may be irradiated with subsequent subtotal resection to improve longevity. Adjuvant therapy is also necessary for malignant tumors and those that exhibit leptomeningeal spread.[34] Recent studies show an increasing role of bevacizumab in disseminated choroid plexus tumors.[35](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for choroid plexus papillomas include other intraventricular tumors, infectious processes, or vascular lesions.[36] These diagnoses include but are not limited to:

- Ependymoma

- Central neurocytoma

- Subependymal giant cell tumor

- Subependymoma

- Atypical choroid plexus papilloma

- Choroid plexus carcinoma

- Medulloblastoma

- Meningioma

- Chordoid glioma

- Rosette-forming glioneuronal tumor

- Central nervous system lymphoma

- Metastases

- Colloid cyst

- Arachnoid cyst

- Epidermoid or dermoid cyst

- Craniopharyngioma

- Infectious etiology such as cysticercosis caused by the parasite Taenia solium

- Arteriovenous malformation.

Prognosis

Improvements in surgical and intensive care techniques have vastly improved the prognosis of patients with WHO grade I choroid plexus papillomas.[37] Maximum tumor resection correlates with an increase in progression-free and overall survival.[38] Recurrences are rare, and complete resection can be curative. WHO grade II atypical choroid plexus papillomas are more likely to recur than their grade I counterparts. Suprasellar metastases and craniospinal seeding, though rare, have been reported, more commonly in choroid plexus carcinomas.[39]

Complications

Children with features of prolonged raised intracranial pressure, such as papilledema, optic atrophy, and visual loss, may not achieve postoperative resolution of these symptoms.[40] Some may develop persistent cognitive deficits, intracranial hemorrhage, and seizures.[41][27]

The risk of excessive intraoperative blood loss is high for patients with choroid plexus papillomas.[30] Postoperative CSF rhinorrhea has been reported.[42]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Choroid plexus papillomas are rare, benign intracranial tumors occurring primarily in the pediatric population. The typical clinical presentation is that of hydrocephalus, which may present with headache, nausea with or without vomiting, or altered sensorium. However, these lesions may also present with a focal neurologic deficit, such as numbness, weakness, or cranial nerve palsy. Prompt evaluation via cranial imaging is warranted; MRI is preferred. A cure is achievable with complete tumor resection. Choroid plexus papillomas are benign lesions; adjuvant therapy is typically not required.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effectively treating patients with choroid plexus papillomas requires an interprofessional team that includes the referring pediatrician or primary care practitioner, neurosurgeon, anesthesiologist, ophthalmologist, neurologist, and neuroscience specialty–trained nurses. Ancillary staff, including physical, occupational, and speech therapy may also be of assistance for disposition evaluation, treatment while in the hospital, and after-discharge rehabilitation in some instances.

Educating parents and family members is imperative; even though these lesions are benign, complications can occur during surgery. A thorough discussion between the neurosurgeon and family should take place. With adequate preparation and complete removal of the lesion, outcomes are excellent.[43]

Media

References

Boyd MC, Steinbok P. Choroid plexus tumors: problems in diagnosis and management. Journal of neurosurgery. 1987 Jun:66(6):800-5 [PubMed PMID: 3572508]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmith AB, Smirniotopoulos JG, Horkanyne-Szakaly I. From the radiologic pathology archives: intraventricular neoplasms: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2013 Jan-Feb:33(1):21-43. doi: 10.1148/rg.331125192. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23322825]

Ellenbogen RG, Winston KR, Kupsky WJ. Tumors of the choroid plexus in children. Neurosurgery. 1989 Sep:25(3):327-35 [PubMed PMID: 2771002]

Okamoto H, Mineta T, Ueda S, Nakahara Y, Shiraishi T, Tamiya T, Tabuchi K. Detection of JC virus DNA sequences in brain tumors in pediatric patients. Journal of neurosurgery. 2005 Apr:102(3 Suppl):294-8 [PubMed PMID: 15881753]

Zhen HN, Zhang X, Bu XY, Zhang ZW, Huang WJ, Zhang P, Liang JW, Wang XL. Expression of the simian virus 40 large tumor antigen (Tag) and formation of Tag-p53 and Tag-pRb complexes in human brain tumors. Cancer. 1999 Nov 15:86(10):2124-32 [PubMed PMID: 10570441]

Yankelevich M, Finlay JL, Gorsi H, Kupsky W, Boue DR, Koschmann CJ, Kumar-Sinha C, Mody R. Molecular insights into malignant progression of atypical choroid plexus papilloma. Cold Spring Harbor molecular case studies. 2021 Feb:7(1):. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a005272. Epub 2021 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 33608379]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBahar M, Hashem H, Tekautz T, Worley S, Tang A, de Blank P, Wolff J. Choroid plexus tumors in adult and pediatric populations: the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals experience. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2017 May:132(3):427-432. doi: 10.1007/s11060-017-2384-1. Epub 2017 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 28290001]

Dash C, Moorthy S, Garg K, Singh PK, Kumar A, Gurjar H, Chandra PS, Kale SS. Management of Choroid Plexus Tumors in Infants and Young Children Up to 4 Years of Age: An Institutional Experience. World neurosurgery. 2019 Jan:121():e237-e245. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.089. Epub 2018 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 30261376]

Prasad GL, Mahapatra AK. Case series of choroid plexus papilloma in children at uncommon locations and review of the literature. Surgical neurology international. 2015:6():151. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.166167. Epub 2015 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 26500797]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBlamires TL, Maher ER. Choroid plexus papilloma. A new presentation of von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease. Eye (London, England). 1992:6 ( Pt 1)():90-2 [PubMed PMID: 1426409]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRuggeri L, Alberio N, Alessandrello R, Cinquemani G, Gambadoro C, Lipani R, Maugeri R, Nobile F, Iacopino DG, Urrico G, Battaglia R. Rapid malignant progression of an intraparenchymal choroid plexus papillomas. Surgical neurology international. 2018:9():131. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_434_17. Epub 2018 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 30105129]

Khade S, Shenoy A. Ectopic Choroid Plexus Papilloma. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Jan-Mar:13(1):191-194. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.185067. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29492159]

Ikota H, Tanaka Y, Yokoo H, Nakazato Y. Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 20 choroid plexus tumors: their histological diversity and the expression of markers useful for differentiation from metastatic cancer. Brain tumor pathology. 2011 Jul:28(3):215-21. doi: 10.1007/s10014-011-0024-6. Epub 2011 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 21394517]

Prendergast N, Goldstein JD, Beier AD. Choroid plexus adenoma in a child: expanding the clinical and pathological spectrum. Journal of neurosurgery. Pediatrics. 2018 Apr:21(4):428-433. doi: 10.3171/2017.10.PEDS17290. Epub 2018 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 29393815]

Paulus W, Jänisch W. Clinicopathologic correlations in epithelial choroid plexus neoplasms: a study of 52 cases. Acta neuropathologica. 1990:80(6):635-41 [PubMed PMID: 1703384]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTabori U, Shlien A, Baskin B, Levitt S, Ray P, Alon N, Hawkins C, Bouffet E, Pienkowska M, Lafay-Cousin L, Gozali A, Zhukova N, Shane L, Gonzalez I, Finlay J, Malkin D. TP53 alterations determine clinical subgroups and survival of patients with choroid plexus tumors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Apr 20:28(12):1995-2001. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8169. Epub 2010 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 20308654]

Thomas C, Metrock K, Kordes U, Hasselblatt M, Dhall G. Epigenetics impacts upon prognosis and clinical management of choroid plexus tumors. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2020 May:148(1):39-45. doi: 10.1007/s11060-020-03509-5. Epub 2020 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 32342334]

Zhou WJ, Wang X, Peng JY, Ma SC, Zhang DN, Guan XD, Diao JF, Niu JX, Li CD, Jia W. Clinical Features and Prognostic Risk Factors of Choroid Plexus Tumors in Children. Chinese medical journal. 2018 Dec 20:131(24):2938-2946. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.247195. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30539906]

Piguet V, de Tribolet N. Choroid plexus papilloma of the cerebellopontine angle presenting as a subarachnoid hemorrhage: case report. Neurosurgery. 1984 Jul:15(1):114-6 [PubMed PMID: 6332280]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJamjoom AA, Sharab MA, Jamjoom AB, Satti MB. Rapid evolution of a choroid plexus papilloma in an infant. British journal of neurosurgery. 2009 Jun:23(3):324-5. doi: 10.1080/02688690902756694. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19533469]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMula-Hussain L, Malone J, Dos Santos MP, Sinclair J, Malone S. CSF Rhinorrhea: A Rare Clinical Presentation of Choroid Plexus Papilloma. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont.). 2021 Jan 31:28(1):750-756. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28010073. Epub 2021 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 33572678]

Navarro-Olvera JL, Covaleda-Rodriguez JC, Diaz-Martinez JA, Aguado-Carrillo G, Carrillo-Ruiz JD, Velasco-Campos F. Hemifacial Spasm Associated with Compression of the Facial Colliculus by a Choroid Plexus Papilloma of the Fourth Ventricle. Stereotactic and functional neurosurgery. 2020:98(3):145-149. doi: 10.1159/000507060. Epub 2020 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 32316018]

Li Y, Chetty S, Feldstein VA, Glenn OA. Bilateral Choroid Plexus Papillomas Diagnosed by Prenatal Ultrasound and MRI. Cureus. 2021 Mar 6:13(3):e13737. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13737. Epub 2021 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 33842115]

Cao LR, Chen J, Zhang RP, Hu XL, Fang YL, Cai CQ. Choroid Plexus Papilloma of Bilateral Lateral Ventricle in an Infant Conceived by in vitro Fertilization. Pediatric neurosurgery. 2018:53(6):401-406. doi: 10.1159/000491639. Epub 2018 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 30391955]

Pandey SK, Mani SE, Sudhakar SV, Panwar J, Joseph BV, Rajshekhar V. Reliability of Imaging-Based Diagnosis of Lateral Ventricular Masses in Children. World neurosurgery. 2019 Apr:124():e693-e701. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.196. Epub 2019 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 30660880]

Dangouloff-Ros V, Grevent D, Pagès M, Blauwblomme T, Calmon R, Elie C, Puget S, Sainte-Rose C, Brunelle F, Varlet P, Boddaert N. Choroid Plexus Neoplasms: Toward a Distinction between Carcinoma and Papilloma Using Arterial Spin-Labeling. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2015 Sep:36(9):1786-90. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4332. Epub 2015 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 26021621]

Laarakker AS, Nakhla J, Kobets A, Abbott R. Incidental choroid plexus papilloma in a child: A difficult decision. Surgical neurology international. 2017:8():86. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_386_16. Epub 2017 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 28607820]

Ito H, Nakahara Y, Kawashima M, Masuoka J, Abe T, Matsushima T. Typical Symptoms of Normal-Pressure Hydrocephalus Caused by Choroid Plexus Papilloma in the Cerebellopontine Angle. World neurosurgery. 2017 Feb:98():875.e13-875.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2016.11.106. Epub 2016 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 27913261]

Toescu SM, James G, Phipps K, Jeelani O, Thompson D, Hayward R, Aquilina K. Intracranial Neoplasms in the First Year of Life: Results of a Third Cohort of Patients From a Single Institution. Neurosurgery. 2019 Mar 1:84(3):636-646. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyy081. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29617945]

Aljared T, Farmer JP, Tampieri D. Feasibility and value of preoperative embolization of a congenital choroid plexus tumour in the premature infant: An illustrative case report with technical details. Interventional neuroradiology : journal of peritherapeutic neuroradiology, surgical procedures and related neurosciences. 2016 Dec:22(6):732-735 [PubMed PMID: 27605545]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJung GS, Ruschel LG, Leal AG, Ramina R. Embolization of a giant hypervascularized choroid plexus papilloma with onyx by direct puncture: a case report. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2016 Apr:32(4):717-21. doi: 10.1007/s00381-015-2915-z. Epub 2015 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 26438551]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim IY, Niranjan A, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, Lunsford LD. Gamma knife radiosurgery for treatment resistant choroid plexus papillomas. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2008 Oct:90(1):105-10. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9639-9. Epub 2008 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 18587534]

Turkoglu E, Kertmen H, Sanli AM, Onder E, Gunaydin A, Gurses L, Ergun BR, Sekerci Z. Clinical outcome of adult choroid plexus tumors: retrospective analysis of a single institute. Acta neurochirurgica. 2014 Aug:156(8):1461-8; discussion 1467-8. doi: 10.1007/s00701-014-2138-1. Epub 2014 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 24866474]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMorshed RA, Lau D, Sun PP, Ostling LR. Spinal drop metastasis from a benign fourth ventricular choroid plexus papilloma in a pediatric patient: case report. Journal of neurosurgery. Pediatrics. 2017 Nov:20(5):471-479. doi: 10.3171/2017.5.PEDS17130. Epub 2017 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 28841111]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAnderson MD, Theeler BJ, Penas-Prado M, Groves MD, Yung WK. Bevacizumab use in disseminated choroid plexus papilloma. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2013 Sep:114(2):251-3. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1180-9. Epub 2013 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 23761024]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMuly S, Liu S, Lee R, Nicolaou S, Rojas R, Khosa F. MRI of intracranial intraventricular lesions. Clinical imaging. 2018 Nov-Dec:52():226-239. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2018.07.021. Epub 2018 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 30138862]

Siegfried A, Morin S, Munzer C, Delisle MB, Gambart M, Puget S, Maurage CA, Miquel C, Dufour C, Leblond P, André N, Branger DF, Kanold J, Kemeny JL, Icher C, Vital A, Coste EU, Bertozzi AI. A French retrospective study on clinical outcome in 102 choroid plexus tumors in children. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2017 Oct:135(1):151-160. doi: 10.1007/s11060-017-2561-2. Epub 2017 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 28677107]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSafaee M, Oh MC, Sughrue ME, Delance AR, Bloch O, Sun M, Kaur G, Molinaro AM, Parsa AT. The relative patient benefit of gross total resection in adult choroid plexus papillomas. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2013 Jun:20(6):808-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.08.003. Epub 2013 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 23623658]

Abdulkader MM, Mansour NH, Van Gompel JJ, Bosh GA, Dropcho EJ, Bonnin JM, Cohen-Gadol AA. Disseminated choroid plexus papillomas in adults: A case series and review of the literature. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2016 Oct:32():148-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2016.04.002. Epub 2016 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 27372242]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFujimura M, Onuma T, Kameyama M, Motohashi O, Kon H, Yamamoto K, Ishii K, Tominaga T. Hydrocephalus due to cerebrospinal fluid overproduction by bilateral choroid plexus papillomas. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2004 Jul:20(7):485-8 [PubMed PMID: 14986042]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWard C, Phipps K, de Sousa C, Butler S, Gumley D. Treatment factors associated with outcomes in children less than 3 years of age with CNS tumours. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2009 Jun:25(6):663-8. doi: 10.1007/s00381-009-0832-8. Epub 2009 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 19247674]

Lechanoine F, Zemmoura I, Velut S. Treating Cerebrospinal Fluid Rhinorrhea without Dura Repair: A Case Report of Posterior Fossa Choroid Plexus Papilloma and Review of the Literature. World neurosurgery. 2017 Dec:108():990.e1-990.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.08.121. Epub 2017 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 28866068]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHallaert GG, Vanhauwaert DJ, Logghe K, Van den Broecke C, Baert E, Van Roost D, Caemaert J. Endoscopic coagulation of choroid plexus hyperplasia. Journal of neurosurgery. Pediatrics. 2012 Feb:9(2):169-77. doi: 10.3171/2011.11.PEDS11154. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22295923]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence