Introduction

Colitis is inflammation of the mucosal lining of the colon which may be acute or chronic. Colitis is common and increasing in prevalence worldwide. Patients with colitis present with watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, tenesmus, urgency, fever, tiredness, and blood in the stool. However, colitis has different types and results from several mechanisms including infection, autoimmunity, ischemia, and drugs. Also, it may occur secondary to immune deficiency disorders or secondary to exposure to radiation. Because the clinical presentation can be the same across different types of colitis, there is a need for a review presenting an approach to assess patients presenting with colitis. Searching the literature reveals that this area is deficient, and nearly most publications are focused on one aspect of colitis or are disease-based articles. This review discusses the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, evaluation, differential diagnosis, complications and management of patients with colitis.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

In adults, colitis may be the result of infection, inflammatory bowel disease, microscopic colitis, ischemia, drugs, secondary to immune deficiency disorders, or radiation.

- Infection: Bacterial infections including Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Clostridium difficile responsible for Pseudomembranous colitis. Parasites such as Entamoeba histolytica, and viruses such as cytomegalovirus.

- Inflammatory bowel disease: This refers to Crohn disease (CD) and Ulcerative colitis (UC).

- Microscopic colitis: This condition is a relatively common cause of chronic watery diarrhea, especially in the elderly. The disease has two main subtypes, collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC), which are very similar clinically with the main distinction being the presence or absence of a thickened subepithelial collagen band. The disease is associated with autoimmune disorders such as celiac disease, type 1 diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, and psoriasis.

- Ischemic colitis: Occurs when there is hypoperfusion in blood supply below that required for the metabolic needs of the colon resulting in colonic mucosal ulceration, inflammation, and hemorrhage.

- Drug-induced colitis: Drugs such as non-steroidal inflammatory drugs, aspirin, proton pump inhibitors, Hreceptor antagonists, beta blockers, statins, immunosuppressive drugs, vasopressors may cause colitis.

- Secondary to immune deficiency disorders

- Tuberculous colitis

- Radiation colitis: This can occur secondary to pelvic radiotherapy for gynecological, urological and rectal cancers.

Epidemiology

Campylobacter jejuni is the number one bacterial cause of diarrheal illness worldwide with an estimated prevalence of 25 to 30 per 100000 population. For Salmonella and Shigella, the prevalence estimates are 20 cases per 100000 population.

Inflammatory bowel disease has been increasing in incidence and prevalence in various regions in the globe with the highest rates in North America and Europe.[1] The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the USA is 263 per 100000 for adults.

Microscopic colitis is most commonly present in older adults with an average age between 50 and 70 years. Microscopic colitis is more common in women than in men with a female-to-male ratio typically higher in CC ranging up to 9 to 1. The incidence of MC is between 1 and 30 per 100000 person-year.

The incidence of ischemic colitis has risen from 6.1 cases per 100000 person-year in 1976 to 1980 to 22.9 per 100000 in 2005 to 2009.[2] While the reason for such increase may be related to several reasons including the improvement in medical intervention and the use of endoscopy in diagnosis, the prevalence of this condition increases with age and comorbidity and hence the increases in incidence as the population ages.

M. tuberculosis colitis is endemic in many countries, and there has been a resurgence of tuberculosis in the Western world. The annual global incidence of tuberculosis is estimated to be 9.4 million cases. The global case fatality rate was 23 to 25% and exceeded 50% in some African countries with high HIV prevalence rates.[3]

Pathophysiology

The pathologic basis includes:

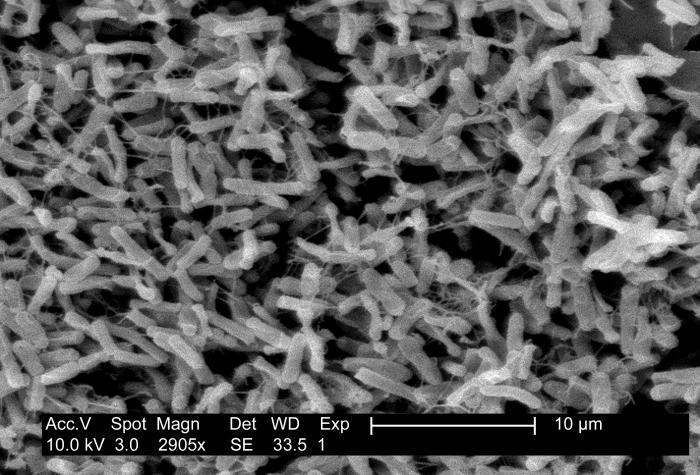

- Infection with Campylobacter jejuni is a result of orally ingested contaminated food or water. Infection influences include several factors including the dose of bacteria ingested, the virulence of organisms, and the immunity of the host. The median incubation period is 2 to 4 days. C jejuni multiplies in the bile and then invades the epithelial layers and travels to the lamina propria producing a diffuse, bloody, edematous enteritis. Pseudomembranous colitis is caused by toxin-producing Clostridium difficile. The disease develops as a result of altered normal microflora (usually by antibiotic therapy such as cephalosporin and beta-lactam antibiotics) that enables overgrowth and colonization of the intestine by Clostridium difficile and production of its toxins.[4]

- Inflammation in ulcerative colitis involves the rectum in 95% of patients and extends proximally in a continuous pattern. The disease may affect the entire colorectum (termed pancolitis) or only limited to the rectum (termed proctitis). Some patients may develop limited terminal ileal involvement (backwash ileitis) that can be challenging to differentiate from Crohn disease.[5][6]

- The pathophysiology of microscopic colitis is not well understood. Several hypotheses have been placed to explain the disease underlying mechanisms and pathogenesis including genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, immune dysregulation to a reaction to a luminal antigen such as various infectious agents and medications, as well as bile acid malabsorption.[7][8][9]

- In ischemic colitis, the duration and severity of hypoperfusion will determine the colonic injury. Reperfusion injury could also be a significant contributing factor. Patients with ischemic colitis usually have (1) comorbidities including heart failure, atherosclerosis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), atrial fibrillation (emboli), concurrent malignancy and hematological disorders (thrombosis). (2) Iatrogenic causes including abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, bowel preparation media for a colonoscopy and colonoscopy. Two mechanisms may cause bowel ischemia, the first is diminished bowel perfusion due to low cardiac output (heart failure, shock), and the second is occlusive disease including atherosclerosis, embolism with inadequate collateral circulation.[10]

- In drug-induced colitis, the pathophysiology and pathology vary and may mimic microscopic colitis and or ischemic colitis.

- In colitis secondary to immune deficiency disorders, several factors might be responsible for colitis and diarrhea including HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy, opportunistic infection (particularly cytomegalovirus), and cryptosporidiosis.

Histopathology

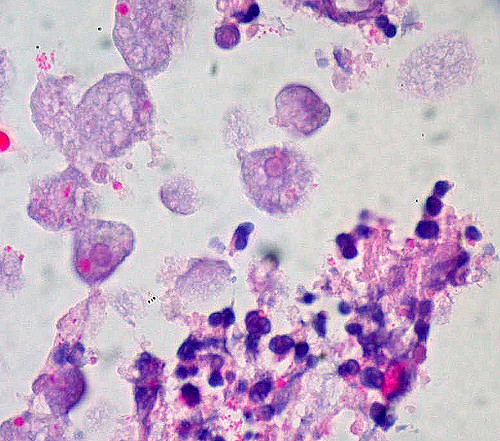

While there is no specific approach for assessing histological changes associated with colitis, the histological pattern approach described by Jessurun seems to be practical and the current recommendation. The patterns include (1) acute colitis associated with colonic infections and drug-induced injuries, inflammation may be patchy or diffuse, and mixed inflammatory cells and abundant neutrophils are usually present (2) focal active colitis, mostly seen in drug-induced injuries, but maybe a manifestation of inflammatory bowel disease especially Crohn disease. (3) Pseudomembranous colitis pattern associated with C. difficile infection, although it can result from other infections such as Shigella, drugs, and radiation injury, (4) hemorrhagic colitis is associated with the entero-hemorrhagic strain of E. coli 0157: H7. The lamina propria appears hemorrhagic and edematous. Fibrin thrombi are present within capillaries, and crypts show ischemic injury, and (5) ischemic colitis associated with acute ischemic colitis. The extent of mucosal injury determines the clinical presentation; however, colonoscopy and biopsies are seldom necessary for patients presenting with acute abdomen due to embolic occlusion, or intestinal obstruction.[5]

History and Physical

Patients with colitis present with abdominal pain, watery diarrhea, fever, urgency, and blood in the stool. Examining doctor should look for red flags such as patient’s age, hemodynamic changes, nocturnal diarrheas, tenesmus, urgency, weight loss, comorbidities, history of heart failure, arrhythmias, autoimmune disorders, detailed history of patient’s medication, signs suggestive of toxic megacolon, and anemia.

In ulcerative colitis, extraintestinal manifestations associated with colitis and disease activity include arthropathies, eye changes (episcleritis, scleritis, uveitis), skin changes (erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum). Other extraintestinal manifestations reported in colitis include sacroiliitis, ankylosing spondylitis, hepatic dysfunction, and primary sclerosing cholangitis.[6]

Evaluation

Diagnosis of colitis has its basis in clinical findings, laboratory tests, endoscopy, and biopsy. Endoscopy and biopsy should not be the primary investigations and may be arranged after a critical evaluation of the patient’s condition and the results from the initial examinations.

- Because colonic infection is a common etiology of colitis and can produce clinical presentations indistinguishable from inflammatory bowel disease, microbiological studies and cultures for bacterial and parasitic infestations should be the primary investigations. Laboratory workup including complete blood count, ESR, CRP, arterial blood gases, activated partial thromboplastin time, serum albumin, total protein, blood urea, creatinine, electrolytes, and purified protein derivative, should be ordered.

- D-lactate levels in the blood could be a sensitive marker of colonic ischemia; however, it is an experimental laboratory test.

- Electrocardiogram, transthoracic and even Holter monitoring may be necessary in patients with ischemic colitis.

- Plain X-ray is of limited value; however, it may be useful in the diagnosis of toxic megacolon, bowel obstruction, and intestinal perforation (pneumoperitoneum). Thumbprinting is a classic finding for mucosal edema though not specific for ischemic colitis.

- Multidetector CT and thin sections, can accurately demonstrate inflammatory changes in the colonic wall and help assess the extent of disease. Ulcerative colitis is distinguishable from granulomatous colitis (Crohn disease) in terms of location of involvement, extent, and appearance of colonic wall thickening, and type of complications.

- Colonoscopy or proctosigmoidoscopy is essential for the final diagnosis; it typically appears normal in microscopic colitis although edema or erythema may present. Ulceration suggests an alternative diagnosis, although these can be present in patients on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Other colonoscopy changes, depending on the etiology, include loss of typical vascular pattern, granularity, friability, and ulceration.

- Several laboratory tests specific to certain colitis may be ordered including perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (P-ANCA), which may present in Crohn disease, anti-saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA), a feature in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which is elevated in patients with active ulcerative colitis.[6]

- Assess the extent, degree, and severity of the disease and any complications.

Treatment / Management

Not all infectious colitis requires antibiotic therapy; patients with mild to moderate C. jejuni or Salmonella infections do not need antibiotic therapy because the infection is self-limited. Treatment with quinolinic acid antibiotics is reserved for patients with dysentery and high fever suggestive of bacteremia. Also, patients with AIDS, malignancy, transplantation, prosthetic implants, valvular heart disease or extreme age will require antibiotic therapy. For mild to moderate cases of C. difficile infection metronidazole is the preferred treatment. In severe cases of C. difficile infection oral vancomycin is recommended. In complicated cases, oral vancomycin with intravenous metronidazole is recommended. Cytomegalovirus colitis is treated with valganciclovir; the duration of treatment should be individualized depending on the clinical picture and laboratory parameters.[11](B3)

5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) drugs are the standard treatment in ulcerative colitis for induction and maintenance of remission of mild and moderate cases. The place of 5-ASA in the management of Crohn disease is controversial. Immunomodulators including azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, and methotrexate, are the mainstay of treatment in maintenance therapy for patients with mild to moderately severe Crohn disease and frequently relapsing ulcerative colitis where 5-ASA drugs failed. Biological therapies, tumor necrosis factor-oe, such as infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab are available for the management of Crohn disease, to get the disease under control and long-term maintenance. Corticosteroids are effective in reducing remission in inflammatory bowel disease and are cheap. However, they are not recommended for maintenance therapy and are associated with serious side effects. Surgery is recommended in patients not responding to medical therapy.[6][12][13]

In microscopic colitis, discontinuation of any offending medication and smoking cessation are vital. While anti-diarrheal medications, bismuth subsalicylate or cholestyramine may help, budesonide is effective in inducing remission and should be the first medication to start.[14] Patients in whom budesonide therapy is not feasible, bismuth salicylate or mesalamine is an option.

Patients with ischemic colitis without peritoneal signs, medical management may be safely employed including intravenous fluid resuscitation, optimizing cardiac output, use of supplementation of oxygen, placing the bowel on rest, parenteral nutrition, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics to cover both aerobic and anaerobic coliform bacteria and close monitoring. Failure of medical management and the development of peritoneal signs or intestinal perforation necessitates surgical intervention and bowel resection.[10][15]

Anti-tuberculous treatment comprising isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for 2 months is recommended in tuberculous colitis followed by isoniazid and rifampin for 7 months. The duration of treatment is nine months, and patients should be regularly followed up for assessing their response to the treatment.[16]

Differential Diagnosis

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Celiac disease (patients with celiac disease who have continued to have watery motions despite being on a strict gluten-free diet should be investigated for microscopic colitis)

- Colorectal cancer

- Diverticulitis

- Toxic megacolon

- Viral/bacterial gastroenteritis

- Other types of colitis

Complications

Complications include:

- Intestinal perforation

- Bowel strictures, fistulas, abscess, and intestinal obstruction

- Fecal incontinence

- Pelvic abscess

- Enterocutaneous fistulas, particularly in Crohn disease

- Pouchitis

- Guillain-Barre syndrome (Campylobacter jejuni colitis, cytomegalovirus colitis, and reported in ulcerative colitis)

- Hemolytic uremic syndrome (enterohemorrhagic E coli, Shigella)

- Encephalopathy, seizures (Shigella)

Toxic megacolon is an uncommon complication of colitis, characterized by total or segmental nonobstructive colonic dilatation, associated with systemic toxicity and has an overall mortality of 19%.[17] Diseases such as ulcerative colitis and pseudomembranous colitis are well-known to be complicated and develop toxic megacolon for over 60% of cases.[18] Other conditions associated with inflammation of colon including Campylobacter and shigella colitis may develop toxic megacolon.

Pearls and Other Issues

The symptoms of colitis are non-specific, detailed medical, examination and laboratory workup are needed; however, endoscopic evaluation and mucosal biopsy are essential to confirm the diagnosis and exclude inflammatory bowel disease-associated colitis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Colitis, depending on its cause, may be self-limited, life-threatening, chronic or recurrent. Patients with chronic and recurrent colitis need lifelong monitoring. The general practitioners have key roles in early diagnosis of the disease, support of the patients and assisting them with smoking cessation and management of their disease. The patients should be encouraged by nursing to take responsibility for their condition and provide knowledge of their pathology and drugs used. The pharmacists should be aware of the disease and drugs that could cause colitis and assist in explaining the potential complications. The nurse and pharmacist should report untoward complications to the clinical team. Other healthcare professionals including nurses need to be mindful of the clinical picture, common presentations, management, and care of patients with chronic and recurrent colitis. The surgeons play a key role with specific aspects of colitis in emergencies and in cases that failed to respond to medical therapy. Patients with chronic colitis develop depression and anxiety and need mental health support. All these various disciplines need to work together collaboratively in an interprofessional team to bring about the best outcomes for patients who have colitis. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, Kaplan GG. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012 Jan:142(1):46-54.e42; quiz e30. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. Epub 2011 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 22001864]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYadav S, Dave M, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, Harmsen WS, Tremaine WJ, Zinsmeister AR, Sweetser SR, Melton LJ 3rd, Sandborn WJ, Loftus EV Jr. A population-based study of incidence, risk factors, clinical spectrum, and outcomes of ischemic colitis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2015 Apr:13(4):731-8.e1-6; quiz e41. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.07.061. Epub 2014 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 25130936]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDye C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathania V, Raviglione MC. Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring Project. JAMA. 1999 Aug 18:282(7):677-86 [PubMed PMID: 10517722]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNapolitano LM, Edmiston CE Jr. Clostridium difficile disease: Diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment update. Surgery. 2017 Aug:162(2):325-348. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.01.018. Epub 2017 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 28267992]

Jessurun J. The Differential Diagnosis of Acute Colitis: Clues to a Specific Diagnosis. Surgical pathology clinics. 2017 Dec:10(4):863-885. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2017.07.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29103537]

Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Apr 29:389(10080):1756-1770. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32126-2. Epub 2016 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 27914657]

Pardi DS. Diagnosis and Management of Microscopic Colitis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2017 Jan:112(1):78-85. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.477. Epub 2016 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 27897155]

Brown WR, Tayal S. Microscopic colitis. A review. Journal of digestive diseases. 2013 Jun:14(6):277-81. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12046. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23419063]

Ianiro G, Cammarota G, Valerio L, Annicchiarico BE, Milani A, Siciliano M, Gasbarrini A. Microscopic colitis. World journal of gastroenterology. 2012 Nov 21:18(43):6206-15. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6206. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23180940]

Washington C, Carmichael JC. Management of ischemic colitis. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2012 Dec:25(4):228-35. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1329534. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24294125]

Tortora A, Purchiaroni F, Scarpellini E, Ojetti V, Gabrielli M, Vitale G, Giovanni G, Gasbarrini A. Colitides. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2012 Nov:16(13):1795-805 [PubMed PMID: 23208963]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNguyen GC, Loftus EV Jr, Hirano I, Falck-Ytter Y, Singh S, Sultan S, AGA Institute Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Management of Crohn's Disease After Surgical Resection. Gastroenterology. 2017 Jan:152(1):271-275. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.10.038. Epub 2016 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 27840074]

Marchioni Beery R, Kane S. Current approaches to the management of new-onset ulcerative colitis. Clinical and experimental gastroenterology. 2014:7():111-32. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S35942. Epub 2014 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 24872716]

Nguyen GC, Smalley WE, Vege SS, Carrasco-Labra A, Clinical Guidelines Committee. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Medical Management of Microscopic Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2016 Jan:150(1):242-6; quiz e17-8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.008. Epub 2015 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 26584605]

Trotter JM, Hunt L, Peter MB. Ischaemic colitis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2016 Dec 22:355():i6600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6600. Epub 2016 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 28007701]

Mukewar S, Mukewar S, Ravi R, Prasad A, S Dua K. Colon tuberculosis: endoscopic features and prospective endoscopic follow-up after anti-tuberculosis treatment. Clinical and translational gastroenterology. 2012 Oct 11:3(10):e24. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2012.19. Epub 2012 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 23238066]

Gan SI, Beck PL. A new look at toxic megacolon: an update and review of incidence, etiology, pathogenesis, and management. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2003 Nov:98(11):2363-71 [PubMed PMID: 14638335]

Ausch C, Madoff RD, Gnant M, Rosen HR, Garcia-Aguilar J, Hölbling N, Herbst F, Buxhofer V, Holzer B, Rothenberger DA, Schiessel R. Aetiology and surgical management of toxic megacolon. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2006 Mar:8(3):195-201 [PubMed PMID: 16466559]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence