Introduction

Craniosynostosis is the result of the early fusion of cranial sutures. These sutures exist to facilitate the passage of the baby through the birth canal and later on allow the expansion and growth of the brain. When one or more sutures close prematurely, the structure of the skull becomes altered, growing on the path of least resistance (perpendicularly to the closed suture) and resulting in an atypically shaped skull leading to increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and having an effect on the respiratory and neurologic systems, as well as the development of the child.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Craniosynostosis can classify as simple when involving a single suture and complex when involving multiple sutures. Another popular way to classify them is in syndromic (Apert, Crouzon, Pfeiffer) and non-syndromic with an isolated finding. [1][3]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of craniosynostosis is 1 per 2000 to 1 per 2500 live births. It has risen with time, the predisposing factors being either environmental (maternal smoking, in utero exposure to teratogens, intrauterine constraint, fetal positioning) or genetic (mutations). Almost 20% of all craniosynostoses are due to genetic causes, most of these being inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, although new mutations arise in 50% of cases.[2] Non-syndromic craniosynostosis occurs in 75% of cases, and 25% account for syndromic craniosynostosis.[2]

The craniosynostoses are classified depending on the suture that is affected, sagittal being affected in 55% to 60% of the cases, coronal (20% to 25%), metopic (approximately15%) and lambdoid (3% to 5%). Clinical identification is usually within the first year of life.[1][2]

History and Physical

As with any other condition, a thorough history and physical examination are most helpful in determining the diagnosis.

While taking the history, it is vital to know if there is any family history of abnormal head shapes, in utero exposure to teratogenic drugs, intrauterine restrains, or an abnormal fetal position, as well as any complications during pregnancy and any delayed milestones.

The physical examination allows the clinician to evaluate whether a suture fusion is present and whether any concomitant features would make the craniosynostosis part of a syndrome, like any congenital anomalies and dysmorphic features.

Assessing the skull is critical. Looking at it from all directions and measuring the head circumference to calculate the cephalic index (maximum breadth of the skull multiplied by 100 divided by the maximum length of the skull). The examiner should also note and touch the scalp to feel any sutural ridging, prominent vessels over the skull, and examine and measure the fontanelles.[2]

Besides these, depending on the severity of the condition, the patient might present with other clinical manifestations as consequences of the craniosynostosis, which must be kept in mind and monitored. Therefore an ophthalmologic examination should be done if any signs of intracranial pressure (ICP) are present which will show papilledema. Examine possible airway obstructions and feeding difficulties.

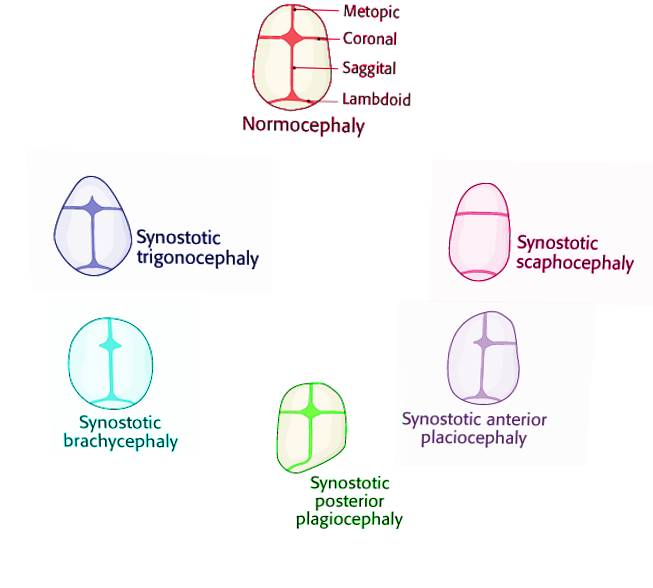

The different non-syndromic craniosynostoses are described below:

- Scaphocephaly or dolichocephaly (premature fusion of the sagittal suture). These patients have a long, narrow-shaped head with a higher anteroposterior diameter. Frontal bossing is often present.[2][1][4]

- Anterior plagiocephaly (premature fusion of 1 coronal suture). The forehead appears flat on the affected side, Harlequin sign (high supraorbital margins seen in radiographs), frontal bossing on the unaffected side, and nasal deviation towards the normal side.[2][1]

- Posterior plagiocephaly (premature fusion of 1 lambdoid suture). Frontal and occipital bossing, ipsilateral ear moved downward, from above the head looks like a trapeze.[2][1][4]

- Trigonocephaly (premature fusion of the metopic suture). The forehead is narrow and pointed; the head has a triangular shape viewed from above, hypotelorism.[2][1]

- Brachycephaly (bi-coronal premature fusion). Short skull, forehead, and occiput flattened but the frontal bone in long (vertically) and prominent, hypertelorism, and Harlequin malformation.[2][1][4]

- Oxycephaly (turricephaly). The fusion of all or most of the cranial sutures.

The different syndrome presenting with craniosynostoses are described below:

- Apert: affects coronal suture. Presenting with midface hypoplasia, hypertelorism (bulging and wide-set eyes), beaked nose, underdeveloped jaw (that leads to crowded teeth), syndactyly of hands and feet, hearing loss. They can have mild to moderate intellectual disabilities.[4][5][6][7]

- Crouzon: affects coronal, sagittal, and/or lambdoid sutures; features midface hypoplasia, beaked nose, exophthalmos, hypertelorism, cervical vertebral fusion, and hearing loss. Some can present with cleft lip and/or palate. They usually have normal intelligence.[4][5][6][7]

- Pfeiffer: features brachycephaly (bi-coronal sutures), hypertelorism, maxillary hypoplasia, broad thumbs, great toe, syndactyly, brachydactyly, hearing loss.[4][7]

- Muenke: affecting coronal suture (uni or bilateral); features midface hypoplasia, hypertelorism, macrocephaly, and hearing loss.[4][6][7]

- Kleeblattschadel (cloverleaf deformity, synostosis of the coronal and lambdoid sutures producing a tri-lobar-shaped head): featuring “beak-shaped” nose, maxillary hypoplasia with proptosis, ears displaced inferiorly. This craniosynostosis is associated with hydrocephalus.[8]

Evaluation

Although the diagnosis is clinical, many professionals will require radiologic imaging to evaluate further and confirm the diagnosis.

The most accurate method is the CT scan with 3D reconstruction, where all sutures are assessable, but due to the radiation risk, this option requires thoughtful consideration. Plain x-rays are low-cost. Therefore they are useful to assess infants will low risk of craniosynostosis, but it is not accurate enough. MRI is less accurate when compared to CT, but is still a great method to use, but usually reserved for children in which the CT revealed any anomalies of the brain.[2]

Ultrasound is a low-cost modality (but technician-dependent) that can only be used with open fontanelles but is very useful to visualize and follow up the sutures at every examination.

New modalities are now in use, like GRASE (gradient-and-spin-echo), a type of MRI, which enhances bone-soft tissue boundaries showing the cranial sutures as hyperintense.[2]

When encountered with syndromic craniosynostosis, genetic testing is the usual followup (recommended mostly when two or more sutures are affected), testing for FGF receptor genes, which have been the genes most commonly related to these syndromes. FGFR2 and FGFR3 undergo testing, as well as transcription factors (TWIST, MSX2). Increasing levels of research have taken place to understand and determine the genetic causes of these syndromes. To date, 57 genes have been identified to have a relationship and be the underlying cause of the craniosynostosis, the most common ones being the ones mentioned above.[2][3][6]

Treatment / Management

The management of these patients depends on the kind of craniosynostosis. The uncomplicated and non-syndromic types can be managed surgically but electively compared to some syndromic forms that require urgent surgical intervention due to the involvement of the airway, ophthalmologic, and neurological system.[1][2] A conservative approach with remodeling helmets could be attempted first in cases in which unilateral craniosynostosis is not too severe.[2]

The extent, as well as the type of surgery, depends on the age and presentation of the patient. Two modalities are in use:

- Endoscopic suturectomy: done in a patient less than six months of age because the bone is more flexible and manageable by an endoscope. The postoperative recovery is faster, there is less blood loss, and the surgery is shorter compared to open craniotomy. The only downside is that most times, there is a need to combine the surgery with the postoperative use of remodeling helmet for 4 to 6 months.[1][2]

- Open craniotomy: done in patients older than six months because the bones are more rigid and cannot be manipulated as well with an endoscope. This modality allows for a better remodeling of the skull and decreases the need for helmet use postoperatively.[1][2]

The main goal of surgery is to create enough space in the cranial vault for the brain to grow and develop properly as well as to provide the child with a more decent-looking appearance.

The best time in which the correction should be done is between 6 to 12 months of age when there are no signs of increased ICP or airway compromise, and this correlates with the period in which the infant’s brain and head grow the most.[2]

The need for additional intervention can always arise and is more bound to occur in syndromic cases.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

Positional plagiocephaly requires differentiation from craniosynostosis. It has no premature fusion of sutures. It presents with a parallelogram of the head, ipsilateral anterior displacement of the ear and head, ipsilateral occipital flattening with contralateral occipital bossing.[5][6] The prevalence has increased over time due to the "back to sleep campaign" to reduce the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome. Still, the only concern is cosmetic, and it can be managed supportively by alternating the side of the head on which the baby sleeps. Remodeling helmets are also an option. This condition does not require surgical intervention and does not affect neurologic development. Parents should be reassured and instructed to continue making the baby sleep on his back.[2][9][1]

Prognosis

Left untreated, craniosynostosis can affect the development of the child; this is due to the restriction for growth of the brain and damage to the brain tissue due to increased intracranial pressure.[5][6] The degree of developmental delay hinges on the kind of craniosynostosis. Children with sagittal synostosis have a lower risk of learning disabilities compared to those with metopic, uni-coronal, or lambdoid synostosis. With early identification of developmental gaps and placement in support programs, a negative academic and cognitive outcome for these children could be reduced if not prevented.[2][10]

When surgical intervention occurs promptly, cases have an excellent outcome with relatively normal growth and development. Follow up for another fusion of sutures and head growth is crucial to determine the need for re-intervention in these patients, with a particular focus on syndromic craniosynostosis. [2][1]

Complications

Surgical treatment can lead to several complications like postoperative hyperthermia (most common), infections (meningitis), seizures, subgaleal hematoma, subcutaneous hematoma, and cerebrospinal fluid leakage. The risk of complications increases with reintervention, as well as with open craniotomy (compared to the endoscopic approach where the complications are minimal). In case of severe blood loss, mortality and morbidity can reach up to 50%.[2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

The occurrence of syndromic craniosynostosis is only preventable with genetic counseling.[11] As for the positional plagiocephaly, alternating the side of the head that the baby sleeps on helps prevent it.[9]

Pearls and Other Issues

- Craniosynostosis is a premature fusion of one or more sutures and is a common condition (1 per 2000 to 1 per 2500) that can categorize into syndromic and non-syndromic types.

- The most common non-syndromic craniosynostosis is by premature fusion of the sagittal suture.

- In syndromic cases, the most commonly affected genes are FGF receptor genes.

- Early surgical management between 6 to 12 months is the treatment of choice in syndromic craniosynostosis.

- Positional plagiocephaly does not require surgical therapy.

- The degree of developmental delay is dependent on the kind of craniosynostosis. Children with sagittal synostosis have a lower risk of learning disabilities compared to those with metopic, uni-coronal, or lambdoid synostosis.

- With early identification of developmental gaps and placement in support programs, a negative academic and cognitive outcome for these children could be reduced if not prevented.

- An interprofessional approach to care is essential in the management of patients.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional approach to care is essential in the management of patients with craniosynostosis, especially those with syndromic craniosynostosis. The team should include pediatrics, neurosurgery, plastic surgery, maxillofacial surgery, ophthalmology, genetics, nurses, respiratory sleep physician, orthopedics, and later on, a developmental specialist.[7]

Referral to a nurse specializing in developmental pediatric care for early intervention and developmental monitoring is important in the implementation of a special plan of education to improve the patient's possible weaknesses since they are at risk of developmental delay. Early identification and referral for prompt management are key in giving these patients their best chance.

They will also require physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy as well as possible hearing or vision aid, and placement in an appropriate school setting.

Each of these disciplines must engage the other members of the interprofessional healthcare team. They must communicate their findings and ensure that other clinicians are aware of changes or therapy results that have ramifications across interprofessional lines. Only then can outcomes be optimally directed. [Level 5]

The follow up is for a prolonged period because as the infant grows, physical and mental deficits may come to light. With early identification of developmental gap and placement in support programs, a negative academic and cognitive outcome for these children is minimized, if not prevented

The outcomes for most children are guarded and depend on the type of genetic syndrome acquired. But with adequate nursing care, the lives of some children can be improved.

Media

References

Johnson D, Wilkie AO. Craniosynostosis. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2011 Apr:19(4):369-76. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.235. Epub 2011 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 21248745]

Kajdic N, Spazzapan P, Velnar T. Craniosynostosis - Recognition, clinical characteristics, and treatment. Bosnian journal of basic medical sciences. 2018 May 20:18(2):110-116. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2017.2083. Epub 2018 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 28623672]

Senarath-Yapa K, Chung MT, McArdle A, Wong VW, Quarto N, Longaker MT, Wan DC. Craniosynostosis: molecular pathways and future pharmacologic therapy. Organogenesis. 2012 Oct-Dec:8(4):103-13. doi: 10.4161/org.23307. Epub 2012 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 23249483]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGovernale LS, Craniosynostosis. Pediatric neurology. 2015 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 26371995]

Padmanabhan V, Hegde AM, Rai K. Crouzon's syndrome: A review of literature and case report. Contemporary clinical dentistry. 2011 Jul:2(3):211-4. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.86464. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22215936]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAgochukwu NB, Solomon BD, Muenke M. Impact of genetics on the diagnosis and clinical management of syndromic craniosynostoses. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2012 Sep:28(9):1447-63. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1756-2. Epub 2012 Aug 8 [PubMed PMID: 22872262]

O'Hara J, Ruggiero F, Wilson L, James G, Glass G, Jeelani O, Ong J, Bowman R, Wyatt M, Evans R, Samuels M, Hayward R, Dunaway DJ. Syndromic Craniosynostosis: Complexities of Clinical Care. Molecular syndromology. 2019 Feb:10(1-2):83-97. doi: 10.1159/000495739. Epub 2019 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 30976282]

M Das J,Bhimji SS, Pfeiffer Syndrome 2019 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 30422477]

Linz C, Kunz F, Böhm H, Schweitzer T. Positional Skull Deformities. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2017 Aug 7:114(31-32):535-542. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0535. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28835328]

Shim KW, Park EK, Kim JS, Kim YO, Kim DS. Neurodevelopmental Problems in Non-Syndromic Craniosynostosis. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2016 May:59(3):242-6. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2016.59.3.242. Epub 2016 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 27226855]

Kutkowska-Kaźmierczak A, Gos M, Obersztyn E. Craniosynostosis as a clinical and diagnostic problem: molecular pathology and genetic counseling. Journal of applied genetics. 2018 May:59(2):133-147. doi: 10.1007/s13353-017-0423-4. Epub 2018 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 29392564]