Introduction

The thyroid gland is a midline endocrine structure located in the anterior neck. It lies in front of the trachea, and the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the infrahyoid muscles cover its lateral and anterior borders. The sternocleidomastoid is a large muscle located in the posterior triangle of the neck. This muscle runs anterior to the common carotids and is a typical muscular landmark during neck surgery. The strap muscles, also known as the infrahyoid muscles, are composed of four paired muscles – the sternohyoid, the sternothyroid, the omohyoid, and the thyrohyoid. These muscles have both a superficial layer, composed of the sternohyoid and the omohyoid, and a deep layer, consisting of the sternothyroid and the thyrohyoid.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The lateral surface of the thyroid is comprised of the sternothyroid muscle, whose attachment to the thyroid cartilage supports the superior pole of the thyroid gland. Anteriorly lies the superior belly of the omohyoid and the sternohyoid muscles. The anterior aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle overlaps these two muscles. Avascular fascia joins the sternothyroid and sternohyoid muscles midline, and this fascia commonly gets incised during thyroid surgery. Together, the infrahyoid muscles are important for swallowing and phonation due to their actions of gross movement of and positioning of the larynx. The sternocleidomastoid muscle arises from the clavicle and sternum and has a medial and lateral head. The muscle acts to turn the head towards the ipsilateral side and to turn the shoulder towards the contralateral side.[2]

Embryology

The muscles of the head and neck derive from six pairs of branchial arches. These arches form during weeks 4 to 7 of gestation. The arches consist of neural crest cells and mesoderm, with the mesodermal layer giving rise to the muscles surrounding the thyroid gland. The thyroid gland is endodermal in origin. It descends anteriorly and inferiorly, beginning at the foramen cecum in the posterior tongue. The thyroid will reach its final anatomical location by the seventh week of gestation, midline and anterior to the trachea.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The thyroid region has an extensive blood supply. The main arterial supply to the thyroid gland is the superior and inferior thyroid arteries. These two arteries have a rich collateral system composed of many branches and anastomoses, both ipsilaterally and contralaterally. The superior thyroid artery is a branch of the external carotid artery. It courses under the omohyoid and sternohyoid muscles and runs lateral to the larynx. The cricothyroid artery, a branch of the superior thyroid artery, enters the cricothyroid muscle’s superficial surface and contributes to its blood supply. The inferior thyroid artery is a branch of the thyrocervical trunk, which arises from the subclavian artery. Most of its branches supply blood to the lateral aspect of the thyroid gland and the lateral muscles of the thyroid region. Specifically, the muscular branches of the inferior lateral artery supply the infrahyoid, anterior scalene, longus colli, and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles. In 10% of the population, an additional artery called the thyroid ima may be present and contribute to the blood supply of the thyroid.

The superior, middle, and inferior thyroid veins provide the venous drainage of the thyroid region. The superior thyroid vein courses along the superior thyroid artery and eventually drains into the internal jugular vein. The middle thyroid vein runs directly lateral to the internal jugular vein. The left inferior thyroid vein drains into the left brachiocephalic vein. The right inferior thyroid vein may drain into either the left brachiocephalic vein or the right brachiocephalic vein.

There is an abundant lymphatic supply to the thyroid region, including the prelaryngeal, paratracheal, pretracheal, and cervical nodes. The lower deep cervical nodes and the paratracheal nodes drain the isthmus and inferior thyroid. The cervical nodes and superior pretracheal nodes drain the superior thyroid. After immediate drainage to these periglandular lymph nodes, further lymphatic drainage continues to the mediastinal nodes.[2]

Nerves

The infrahyoid muscles receive innervation from the deep ansa cervicalis (C1 to C3), a branch of the cervical plexus. The thyrohyoid muscle also receives nerve supply by the superior ansa cervicalis going alongside the hypoglossal nerve.[3]

The sternocleidomastoid muscle receives motor innervation from the ipsilateral spinal accessory nerve (CN XI). The ventral rami of C2 and C3 from the cervical plexus provide sensory input to the sternocleidomastoid.

Muscles

The infrahyoid muscles and the sternocleidomastoid muscle directly border the thyroid gland. These muscles and other important muscles of note in the thyroid region are:

Infrahyoid muscles: Together, the infrahyoid muscles play an active role in swallowing through the movement of the larynx. The omohyoid, sternohyoid, and thyrohyoid act to depress the hyoid bone. The thyrohyoid elevates the larynx whereas the sternothyroid depress the larynx. The omohyoid also has a function in ensuring proper venous blood return through its attachment to the carotid sheath. When the omohyoid pulls on the carotid sheath, the internal jugular vein maintains a low-pressure system, leading to increased blood return to the superior vena cava.

Sternocleidomastoid muscle: the sternocleidomastoid muscle arises from the clavicle and sternum. It is composed of two heads—a lateral/clavicular head and a medial/sternal head. Upon contraction of one side of the muscle, it rotates the head towards the contralateral side of the body and pulls the head towards the ipsilateral shoulder. When both sternocleidomastoid muscles act together, they function to flex the cervical vertebral column. Working together, they also aid in forced inspiration through elevation of the thorax.

Cricothyroid muscle: the cricothyroid muscle is a relatively thin and flat muscle located on the lateral and anterior segment of the cricoid cartilage. It inserts at the lower laminar and inferior cornu of the thyroid cartilage. It is the only tensor muscle of the larynx that aids in phonation. When stimulated, the muscle elongates and tenses the vocal cords. It does this by gently tilting the thyroid cartilage forward. With this action, the distance between the angle of the thyroid and vocal processes is increased, with consequent elongation of the folds; the eventual result is a higher pitch in voice.[4]

Platysma: the platysma muscles are paired, superficial muscles arising from the subcutaneous layer and fascia of the neck. The platysma functions to depress the lower lip and draws down the lower lip. It also tenses the skin of the neck during clenching of the jaw, often seen when making facial expressions of anger. It receives innervation by the cervical branch of the facial nerve (CN XII).[5]

Suprahyoid muscles: the suprahyoid muscles are composed of the digastrics, stylohyoid, mylohyoid, and geniohyoid. During swallowing, these muscles act to elevate the hyoid bone and the base of the tongue. Additionally, they function to depress the mandible when the hyoid bone is in a fixed position. The mylohyoid branch of the inferior alveolar nerve supplies the anterior belly of the digastric muscle and the mylohyoid muscle. The facial nerve provides innervation to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and the stylohyoid muscle. Nerve fibers from C1 innervate the geniohyoid muscle.[2]

Physiologic Variants

Sternocleidomastoid innervation: As previously described, the sternocleidomastoid is typically innervated by the spinal accessory nerve, C2, and C3 ventral rami. Multiple aberrant variants of innervation to the sternocleidomastoid have been described, such as the branches for the external laryngeal nerve, the hypoglossal nerve, accessory branches of the vagus nerve, branches of the facial nerve, and the transverse cervical nerve.[6]

Cricothyroid innervation: In the majority of the population, the cricothyroid muscle gets its innervation solely by the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. Cases reports exist of the cricothyroid muscle receiving nerve supply from branches of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, which is the nervous supply to the endolaryngeal muscles. This anomaly is important to consider during thyroid surgery, as possible changes can arise to the patient’s voice if the innervation to the cricothyroid muscle is injured.[7]

Surgical Considerations

The thyroid muscles and surrounding vasculature are essential to consider during surgery in the neck region. The infrahyoid muscles may require incision during thyroid surgery to increase exposure to the thyroid gland. There has been some evidence to show that injury to the infrahyoid muscles during thyroid surgery may impact patients’ voices. The primary finding regarding this injury is that patients’ ability to reach high pitches decreased postoperatively. Additionally, when dissecting the superior pole of the thyroid, it is important not to perform high ligation of the superior thyroid artery. The reason behind this is that the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve is in the vicinity and can be injured. Thus, the patient will present with dysphonia if the nerve has suffered an injury.[8]

Clinical Significance

The thyroid muscles are critical anatomical landmarks during thyroid surgery, and injury to these muscles can result in various pathologies:

Infrahyoid muscle paralysis: Damage to the ansa cervicalis can occur due to the result of a trauma in the cervical spine; this may result in infrahyoid muscle paresis or even paralysis. This injury may present in various manifestations, such as a hoarse voice, swallowing difficulties, and throat tightness. The ansa cervicalis may also be deliberately sacrificed during a radical neck dissection. This procedure may be necessary when malignancy is found in the head and neck region and can cause permanent deficits for the patient postoperatively.

Torticollis: Unilateral shortening or tightening of the sternocleidomastoid muscle may result in a pathology known as torticollis—flexion, extension, or twisting of the neck to one side of the body. The muscular contractions causing torticollis can be intermittent or sustained, acute or chronic, acquired or congenital. It is oftentimes associated with muscle spasms and can be painful. Surgical correction may be indicated in severe cases.[9][10][9]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

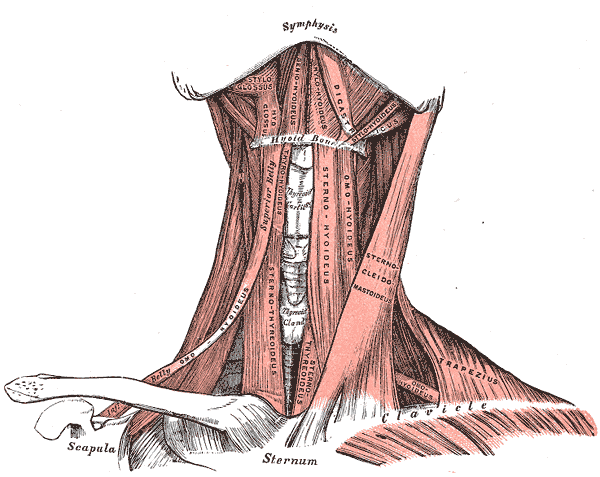

Anterior Neck Muscles and Related Structures. This illustration shows the supra- and infrahyoid, styloglossus, hyoglossus, geniohyoideus, mylohyoideus, digastricus, stylohyoideus, omohyoideus, sternothyroideus, sternohyoideus, omohyoideus, sternocleidomastoideus, trapezius, and omohyoideus muscles. The mandibular symphysis, thyroid cartilage, thyroid gland, hyoid bone, clavicles, scapula, and sternum are also shown.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Gervasio A, Mujahed I, Biasio A, Alessi S. Ultrasound anatomy of the neck: The infrahyoid region. Journal of ultrasound. 2010 Sep:13(3):85-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2010.09.006. Epub 2010 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 23396844]

Allen E, Fingeret A. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Thyroid. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262169]

Meguid EA, Agawany AE. An anatomical study of the arterial and nerve supply of the infrahyoid muscles. Folia morphologica. 2009 Nov:68(4):233-43 [PubMed PMID: 19950073]

Pei YC, Fang TJ, Li HY, Wong AM. Cricothyroid muscle dysfunction impairs vocal fold vibration in unilateral vocal fold paralysis. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Jan:124(1):201-6. doi: 10.1002/lary.24229. Epub 2013 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 23712513]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencede Almeida ART, Romiti A, Carruthers JDA. The Facial Platysma and Its Underappreciated Role in Lower Face Dynamics and Contour. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2017 Aug:43(8):1042-1049. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001135. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28394862]

Paraskevas G, Lazaridis N, Spyridakis I, Koutsouflianiotis K, Kitsoulis P. Aberrant innervation of the sternocleidomastoid muscle by the transverse cervical nerve: a case report. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2015 Apr:9(4):AD01-2. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/11787.5757. Epub 2015 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 26023545]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMiyauchi A, Masuoka H, Nakayama A, Higashiyama T. Innervation of the cricothyroid muscle by extralaryngeal branches of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The Laryngoscope. 2016 May:126(5):1157-62. doi: 10.1002/lary.25691. Epub 2015 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 26509739]

Tinckler LF. Strap muscles in thyroid surgery: to cut or not to cut? Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 1993 Sep:75(5):378-9 [PubMed PMID: 8215159]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKessomtini W, Chebbi W. [Congenital muscular torticollis in children]. The Pan African medical journal. 2014:18():190. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.18.190.4863. Epub 2014 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 25419317]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDo TT. Congenital muscular torticollis: current concepts and review of treatment. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2006 Feb:18(1):26-9 [PubMed PMID: 16470158]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence