Introduction

Cryptococcus is an encapsulated hetero-basidiomycetous fungus that is an opportunistic pathogen. These fungi are present in the environment in sexual and asexual forms. These fungi infect immunocompromised host as well as immunocompetent persons. These fungi show a strong tropism for the central nervous system but are also known for their dermatographism.[1][2][3][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Cryptococcus was first identified in peach juice in Italy by Sanfelice in 1894. In 1895, the first human case was reported. This case was a young woman with a chronic, non-healing skin ulcer on her shin. Yeasts were found in her ulcer, and later at autopsy, yeasts were found in multiple internal organs. These yeasts were Cryptococcus neoformans. The sexual form of this fungus was identified in 1976 and named Filobasidiella neoformans. Thus far, 19 species of Cryptococcus have been identified. Two are pathogenic. There are two serotypes in each of these species. Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans is serotype D, Cryptococcus neoformans var. grubii is serotype A, and Cryptococcus gattii has two serotypes: B and C. The Cryptococcus neoformans genome was published in 2005.[5][6][7]

Cryptococcus species are found in soil contaminated by guano. Cryptococcus gattii has a clear association with eucalyptus trees and a variety of coniferous trees.

The life cycle of this fungus involves two distinct forms, sexual and asexual. The asexual form exists as yeast that divides by narrow-based budding. Yeast forms are primarily seen in clinical specimens. The sexual forms exist in nature in two mating types, “alpha” or “a.” When opposite types mate, meiosis occurs, resulting in chains of basidiospores. These basidiospores are 1 micrometer to 2 micrometer long and are the infectious particles, which are inhaled and reach the alveoli.

Cryptococcus grows well on fungal or bacterial culture mediums in 48 to 72 hours. The colonies appear mucoid.

Epidemiology

Cryptococcus neoformans is endemic in the United States along the Pacific coast extending into Canada. Cryptococcus gattii was recently reported from northern California and Vancouver Island in Canada. C. gattii is endemic in Papua, New Guinea, and northern Australia. While C. neoformans mainly affects patients with AIDS and those who are immunosuppressed, a quarter of patients with C. gattii infections are immunocompetent and healthy.

Prior to the AIDS epidemic, the incidence of Cryptococcus disease was very low at 0.8 per million in the United States, but in 1992 at the height of AIDS epidemic, the incidence increased to 5 per 100,000. Since the use of ART, the incidence has declined to very low levels once again. However, in sub-Saharan Africa, where the AIDS epidemic is raging, the burden of Cryptococcus disease is very high. In sub-Saharan Africa, cryptococcal meningitis is the most common culture-positive meningitis and leads to half a million deaths annually, which is more than mortality due to tuberculosis. Therefore, this disease is a marker of HIV patients with poor access to health care.

Most patients with disseminated disease have an underlying immunocompromised state such as AIDS, transplant patients, those on long-term corticosteroids and those who are prescribed monoclonal antibodies.

Pathophysiology

The polysaccharide capsule, production of melanin, and growth at high temperatures are considered virulence factors for Cryptococcus species. The initial exposure occurs via the lungs through inhalation of basidiospores (1 micrometer to 2 micrometer in length) or dehydrated yeast of appropriate size. Most immunocompetent patients do not succumb to disease unless the inoculum is overwhelming. An effective immune response is generated by alveolar macrophages, which eliminate the yeast. In immunocompromised patients, the yeast continues to divide within the macrophages, which disseminate the infection throughout the body. Skin is the third most common organ system to be involved after lungs and the central nervous system.

History and Physical

Cryptococcus infections present with a wide variety of skin lesions. Skin lesions are frequently a sentinel for disseminated disease; however, primary cutaneous lesions do occur in immunocompetent persons. The primary cutaneous lesion may be a papule, maculopapular lesion with an ulcerated center or a violaceous nodular lesion. Often there is a discharging sinus that connects to the underlying deep abscess or the underlying bone. Some strains of C. neoformans show dermatropism. However, primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Skin lesions in HIV patients can be identical to a bacterial abscess in appearance and clinical presentation. Cutaneous cryptococcosis may present as a cold abscess, without fever and signs of inflammation. Therefore, it is important to send cultures from any abscess drained from an immunocompromised patient. Cutaneous cryptococcal lesions in an AIDS patient may present as crusty, ulcerative lesions that develop slowly. Sometimes the skin lesions of Cryptococcus are umbilicated and can be mistaken for Molluscum contagiosum. Frequently there is simultaneous pulmonary and central nervous system (CNS) involvement.

Cryptococcosis is the third most common invasive fungal infection in organ transplant recipients, after candidiasis and aspergillosis. It is often a late disease occurring at three to ten years post-transplant. Solid organ transplant (SOT) patients have a greater propensity for Cryptococcus skin infections when compared to hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients, for unclear reasons. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can mimic acute bacterial cellulitis in solid organ transplant patients. Cutaneous manifestations can be protean, may mimic an abscess, present as cellulitis that later ulcerates, blisters and shows necrosis, or mimic panniculitis. Primary cutaneous lesions do occur in solid organ transplant patients, but a disseminated disease is more common. In a study of 146 patients with cutaneous cryptococcosis, the following lesions were present in one-third of the patients: nodular mass, papule, ulcer/abscess, and cellulitis. Two-thirds of the skin lesions occurred in the lower extremities, and in 70% of cases, the patients had disseminated disease. The CNS was involved in 90% of cases with disseminated disease.

Evaluation

No skin lesion is characteristic of cutaneous cryptococcosis; therefore, a biopsy is important. A good epidemiological history is important. Patients must be evaluated for an underlying immunosuppressed state. Patients with cutaneous cryptococcosis should be evaluated for the involvement of other organ systems such as the lungs and the CNS.[8][9]

The polysaccharide capsule antigen is a large molecule, and assays have been developed to detect the antigen in serum and other body fluids. If cryptococcal polysaccharide antigen (CA) is present in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), then there is a good chance that the yeast is present as well. The cryptococcal polysaccharide antigen assay is nearly 100% sensitive and 96% to 99.5% specific in serum and 96% to 100% sensitive and 93.5% to 99.8% specific in CSF.

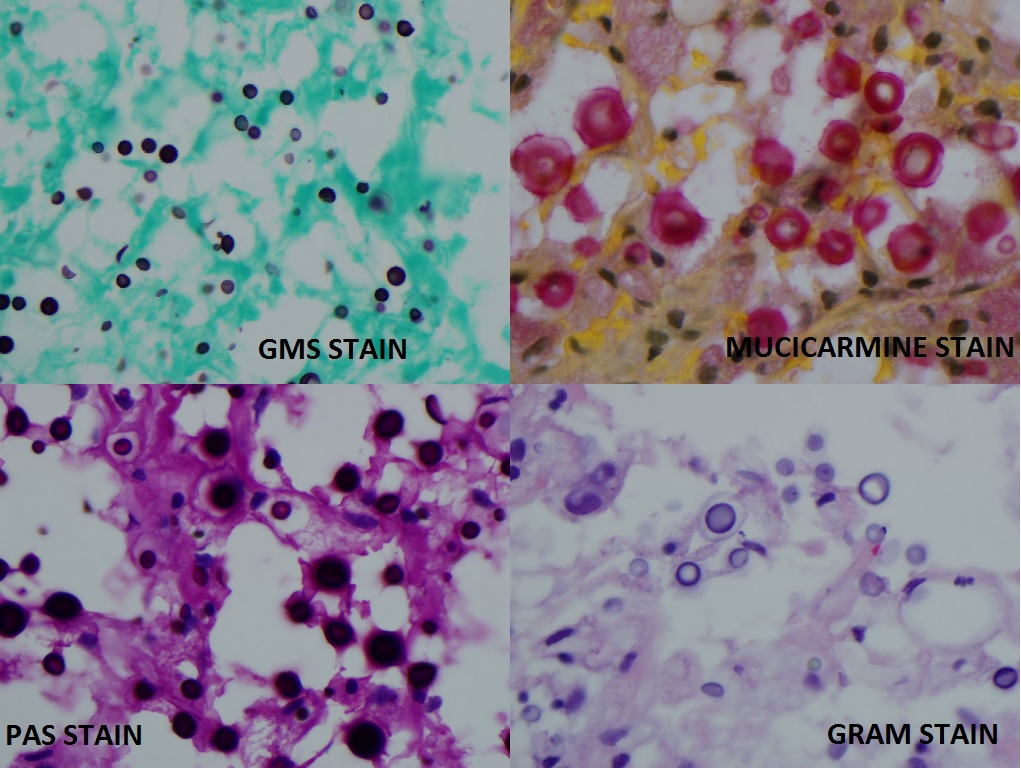

Other microbiological tests to identify Cryptococcus are India-ink preparations and Grocott's methenamine silver stain (GMS). Cryptococcemia can be easily detected by automated systems and seldom results in shock or signs and symptoms of sepsis.

Treatment / Management

Treat HIV patients with a disseminated cryptococcal disease with Amphotericin B (0.7 mg/kg/d to 1.0 mg/kg/d intravenously (IV)) and flucytosine (100 mg/kg/d to 125 mg/kg/d divided into four oral doses) for two weeks, which is the induction phase. Follow this therapy with fluconazole (400 mg [6 mg/kg] per day orally) for a minimum of eight weeks which is the consolidation phase. All forms of amphotericin preparations work equally well, but liposomal amphotericin (AmB) may be preferred in the setting of renal dysfunction. Fluconazole 200 mg daily by mouth is then used as suppressive or maintenance therapy. The duration of maintenance therapy can extend from six months to two years. If the patient is on antiretroviral therapy (ART), then it is reasonable to stop suppression after 12 months of therapy when the viral load is undetectable, and CD4 count is over 100 for three months.

In organ transplant patients with disseminated disease, the regimen is the same, although liposomal amphotericin (AmB) (3 mg/kg/d to 4 mg/kg/d IV) may be preferred. If there is a large fungal burden, a higher dose of AmB (6 mg/kg/d) should be used. If flucytosine is not available for use in the induction phase, then amphotericin therapy should be extended to four weeks. After that, fluconazole maintenance therapy should be continued for at least six to 12 months. Immunosuppressive management should include gradual withdrawal of immunosuppressants, beginning with corticosteroids.

In immunocompetent patients, the principles of therapy are the same. Begin induction therapy with AmB (0.7 mg/kg to 1.0 mg/kg per day IV) plus flucytosine (100 mg/kg per day orally in four divided doses) for at least four weeks. Follow this with eight weeks of consolidation therapy with fluconazole (800 mg [12 mg/kg] per day orally) for eight weeks. After that, continue maintenance therapy with fluconazole (200 mg [3 mg/kg] per day orally) for six to 12 months.

Differential Diagnosis

- Acne vulgaris

- Acute complications of sarcoidosis

- Atypical mycobacterial diseases

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Cellulitis

- Dermatological manifestations of Coccidioidomycosis

- Dermatological manifestations of Kaposi sarcoma

- Molluscum contagiosum

- Pediatric syphilis

- Tuberculosis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of disseminated cryptococcal disease is with an interprofessional team that includes an infectious disease expert, internist, primary care provider, neurologist, pulmonologist and dermatologist. The majority of these patients are immunosuppressed and thus therapy is often extended for several years. The outlook for these patients is guarded and depends on the cause of immunosuppression, extent and other comorbidity. [10](Level V)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ajmal S, Keating M, Wilhelm M. Multifocal Soft Tissue Cryptococcosis in a Renal Transplant Recipient: The Importance of Suspecting Atypical Pathogens in the Immunocompromised Host. Experimental and clinical transplantation : official journal of the Middle East Society for Organ Transplantation. 2021 Jun:19(6):609-612. doi: 10.6002/ect.2017.0292. Epub 2018 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 29957160]

Cohen R, Babushkin F, Shapiro M, Ben-Ami R, Finn T. Cryptococcosis as a cause of nephrotic syndrome? A case report and review of the literature. IDCases. 2018:12():142-148. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2018.05.004. Epub 2018 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 29942774]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHenderson GP, Dreyer S. Ulcerative cellulitis of the arm: a case of primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Dermatology online journal. 2018 Feb 15:24(2):. pii: 13030/qt4rc0q7vx. Epub 2018 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 29630156]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChakradeo K, Paul Chia YY, Liu C, Mudge DW, De Silva J. Disseminated cryptococcosis presenting initially as lower limb cellulitis in a renal transplant recipient - a case report. BMC nephrology. 2018 Jan 27:19(1):18. doi: 10.1186/s12882-018-0815-7. Epub 2018 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 29374464]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWalsh TJ, McCarthy MW. The expanding use of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectroscopy in the diagnosis of patients with mycotic diseases. Expert review of molecular diagnostics. 2019 Mar:19(3):241-248. doi: 10.1080/14737159.2019.1574572. Epub 2019 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 30682890]

Trevijano-Contador N, Zaragoza O. Immune Response of Galleria mellonella against Human Fungal Pathogens. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Dec 26:5(1):. doi: 10.3390/jof5010003. Epub 2018 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 30587801]

Dellière S, Guery R, Candon S, Rammaert B, Aguilar C, Lanternier F, Chatenoud L, Lortholary O. Understanding Pathogenesis and Care Challenges of Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome in Fungal Infections. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Dec 17:4(4):. doi: 10.3390/jof4040139. Epub 2018 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 30562960]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRajasingham R, Wake RM, Beyene T, Katende A, Letang E, Boulware DR. Cryptococcal Meningitis Diagnostics and Screening in the Era of Point-of-Care Laboratory Testing. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2019 Jan:57(1):. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01238-18. Epub 2019 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 30257903]

Farmakiotis D, Kontoyiannis DP. Epidemiology of antifungal resistance in human pathogenic yeasts: current viewpoint and practical recommendations for management. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2017 Sep:50(3):318-324. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.05.019. Epub 2017 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 28669831]

Tugume L, Rhein J, Hullsiek KH, Mpoza E, Kiggundu R, Ssebambulidde K, Schutz C, Taseera K, Williams DA, Abassi M, Muzoora C, Musubire AK, Meintjes G, Meya DB, Boulware DR, COAT and ASTRO-CM teams. HIV-Associated Cryptococcal Meningitis Occurring at Relatively Higher CD4 Counts. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2019 Feb 23:219(6):877-883. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy602. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30325463]