Introduction

Cystic hygromas are one of the most commonly presenting lymphangiomas.[1] They are congenital malformations of the lymphatic drainage system that typically form in the neck, clavicle, and axillary regions. They are most commonly found in young infants or on prenatal ultrasound, and depending on the anatomical site, have the potential to obstruct the airway. Respiratory distress, infection, and aesthetic reasons are the main indications for treatment.[2] The mainstay of management is surgical excision.[3] This article focuses on the presentation, evaluation, and management of cystic hygromas in infants, children, and adults.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

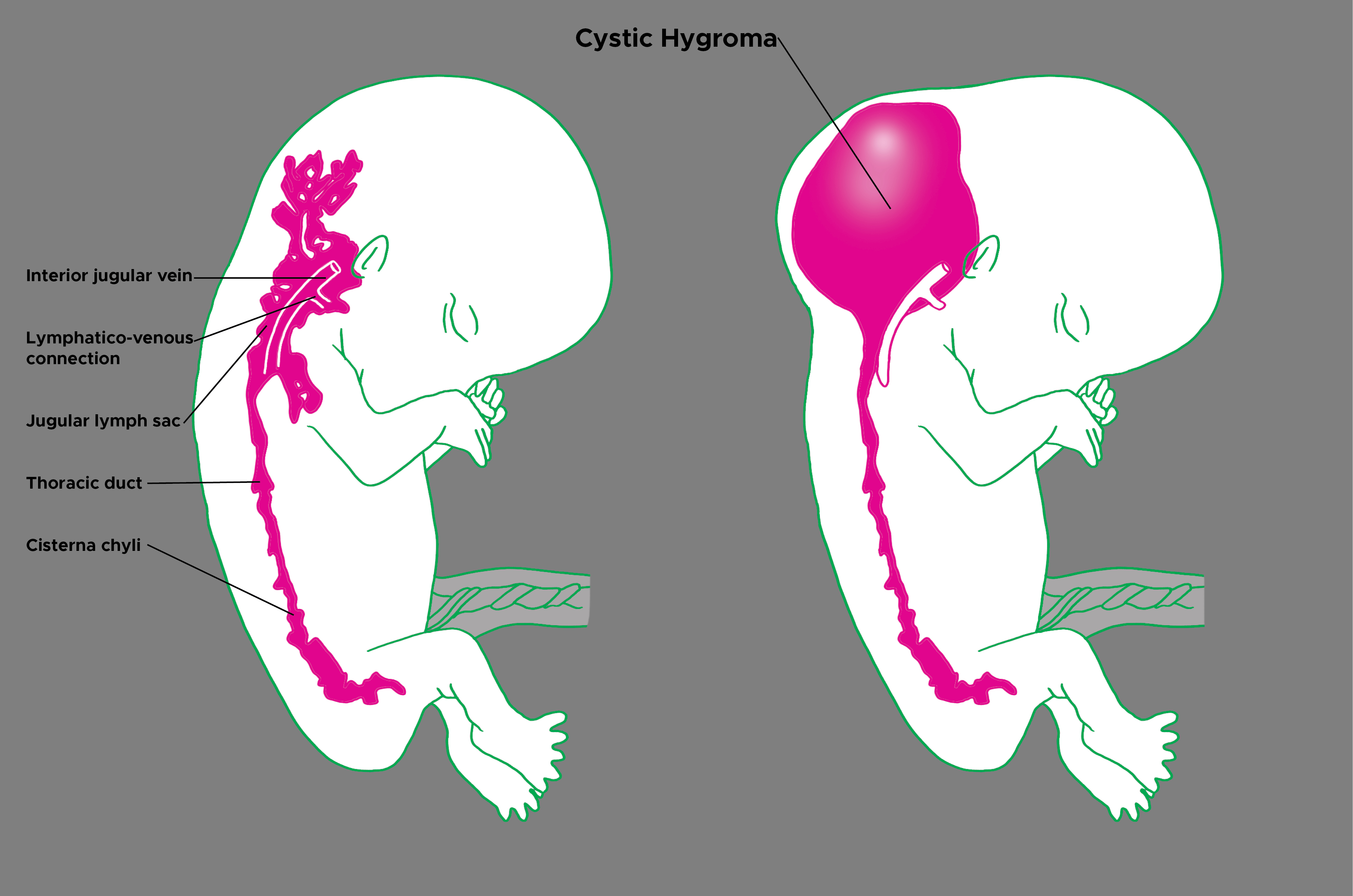

Cystic hygromas are benign cysts that form due to malformations of the lymphatic system.[4] The exact embryonic origin is unclear; however, they are believed to be the result of developmental defects or cystic malformation of dilated lymphatic channels.[4] It is understood that they arise from the remnants of embryonic lymphatic tissue that retains the ability to proliferate.[5] They have been found to be associated with certain conditions, such as chromosome aneuploidies, hydrops fetalis, and intrauterine death.[6]

Epidemiology

Cystic hygromas are rare, accounting for 6% of all benign lesions of infancy and early childhood.[7] They are, however, the most commonly presenting subtype of lymphangioma. 50% of these lesions are present since birth, and the remaining 50% appear by the age of 2.[7] Up to 90% of cases are diagnosed in infants under the age of 2, with most being diagnosed between the ages of 3 and 5.[5] Of all cystic hygroma lesions, 75 to90% are cervical, 20% are axillary, and the remainder is inguinal, retroperitoneal, and thoracic.[4]

Pathophysiology

Cystic hygromas originate embryologically, typically forming at the point of lymphatic-venous collection.[1] It is because of this that they commonly occur in the posterior triangle of the neck.[8] This failure of communication between lymph and venous pathways ultimately causes an accumulation of lymph, resulting in the formation of a cystic structure.[3] They can frequently cross the midline of the body, extending into the axilla and the mediastinum.[4] They may grow rapidly due to the accumulation of lymph itself, blood secondary to hemorrhage, or pus secondary to infection.[9]

Histopathology

Histologically, cystic hygromas are characterized by the proliferation of small lymphatic vessels combined with fibrous tissue.[10] They exhibit large macroscopic cystic spaces that are usually multiloculated.[4] These spaces may be as small as capillary dimensions or as large as cysts that are centimeters in diameter.[5]

History and Physical

The majority of cystic hygromas present in pediatric patients, as adult presentations are considered exceedingly rare. A thorough history from either the patient or a collateral history from the infant’s carer, including a review of systems, is essential to narrowing down the provider’s differential diagnosis.

The patient will commonly present with a large, diffuse, and painless lump. When taking the history, the provider should establish when the lump was first noticed. If the onset was at the time of birth or before the age of 2, this would be in keeping with cystic hygroma. As aforementioned, they can present in adults albeit rare. It is important to enquire about any underlying diseases the individual may have that may predispose the patient to cystic hygromas, such as any underlying chromosomal abnormalities. A thorough review of symptoms should be done to rule out any symptoms of infection, such as fever, rigors, or feeling generally unwell.

Symptoms will depend on the anatomical location of the lump. Depending on their size and site, the patient may present with pain, hoarseness, dysphagia, or shortness of breath. These symptoms can occur following compression of major structures within the neck, such as the larynx, trachea, esophagus, or great vessels.[11] Patients may or may not also complain of restriction of neck movement.

As mentioned previously, cystic hygromas are most commonly found in the posterior triangle of the neck, although they may occur at any anatomical site. On examination, cystic hygromas are soft, fluctuate, and freely mobile, and they transilluminate well.[4] They are typically non-pulsatile and increase in size with coughing and crying.

They can vary in size, ranging from 1-30cm in diameter.[5] The skin overlying the cystic hygroma is often normal, and they are usually painless on palpation. They may be unilateral or bilateral. An infected cystic hygroma is likely to present in a similar fashion; however, they may be exquisitely tender and have erythematous skin overlying them.

Evaluation

Bedside investigations such as basic observations and routine blood tests are likely to be unremarkable in the case of a benign, non-infected cystic hygroma. If the patient has developed an abscess, this may cause a raised white cell count with raised inflammatory markers. Aspiration of the lump in combination with imaging is the gold standard for diagnosing cystic hygromas.

Various imaging modalities like ultrasonography, computerized tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging are used to confirm the diagnosis. Ultrasonography is the least invasive of all and typically shows multicystic lesions with internal septations.[2] CT and MRI can be helpful in delineating the lesion further and for planning surgery as they help to illustrate the involvement and proximity to neighboring structures.[5] Aspiration is likely to produce serous, serosanguinous, or straw-colored fluid.[12]

Occasionally karyotyping might be done in case of any doubt of chromosomal disorder.

Treatment / Management

Cystic hygromas are benign lesions, and if asymptomatic, they do not necessitate treatment. Indications for treatment include infection, hemorrhage, respiratory distress, dysphagia, or disfigurement. The mainstay of management is surgical; however, other options include sclerotherapy, drainage, radio-frequency ablation, or cauterization.[11] Treatment options will be individualized depending on the size, anatomical location, and complications of the lesion.[13] (B3)

Cystic hygromas that develop into abscesses will require antibiotics, antipyretics, and analgesia, with or without subsequent surgical management. Surgical treatment, if needed, is usually withheld till the next three months after the antibiotic course.

Differential Diagnosis

Neck lumps are a common presentation in both children and adults, and therefore have a wide range of differential diagnoses. Lumps that present from birth are more likely to be congenital in origin. Congenital differentials include thyroglossal cysts, branchial cysts, dermoid cysts, or teratomas. Other differentials include infective causes, such as reactive lymphadenopathies, or neoplastic causes, such as lymphoma. The provider should also consider inflammatory causes such as sarcoidosis, traumatic such as hematomas, and vascular causes such as carotid body tumors.

Prognosis

The prognosis of a patient with a cystic hygroma will largely depend on the anatomical site and whether or not the patient develops any secondary complications. Cystic hygromas that are diagnosed prenatally generally have a poorer prognosis than those diagnosed after birth.[8] Surgical excision generally has good outcomes with the complete resolution provided the mass is completely excised; however, the surgical excision rate can be as high as 53% in some cases.[1] This can be improved through the use of adjuncts, such as sclerosing agents.

Cystic hygromas that are left without any intervention are likely to continue to enlarge and cause further complications.

Complications

Complications can arise due to the rapid enlargement of the cystic hygroma, causing infiltration of the neck. This can result in complete or incomplete airway obstruction, dysphagia, and obstructive sleep apnoea. Other complications include hemorrhage within the cystic hygroma leading to infection and later abscess formation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is crucial in order to avoid complications resulting from the delayed presentation. Severe complications such as airway obstruction can rapidly lead to mortality if not promptly treated.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with cystic hygromas may exhibit non-specific signs and symptoms, such as a painless neck lump. The cause may be due to a myriad of diagnoses, including congenital, neoplastic, infective, inflammatory, and vascular etiologies. Although cystic hygroma can be diagnosed clinically, imaging studies are must prior to any further management.

Specialist pediatric surgeons will most likely be involved with the management of pediatric patients presenting with cystic hygromas; however, it is important to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that include a pediatrician, radiologist, and ENT surgeons due to the potential infiltration of surrounding structures.

The nurses are also a vital member of the interprofessional group as they will monitor the patient's vital signs and assist with the education of the patient and family. In the postoperative period for pain and wound infection, the pharmacist will ensure that the patient is on the right analgesics, antiemetics, and appropriate antibiotics. The radiologist also plays a vital role in determining the cause when it comes to interpreting images. The need for meticulous planning and discussion with other professionals involved in the management of the patient is highly recommended to lower the morbidity and improve outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Damaskos C, Garmpis N, Manousi M, Garmpi A, Margonis GA, Spartalis E, Doula C, Michail-Strantzia C, Patelis N, Schizas D, Arkoumanis PT, Andreatos N, Tsourouflis G, Zavras N, Markatos K, Kontzoglou K, Antoniou EA. Cystic hygroma of the neck: single center experience and literature review. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2017 Nov:21(21):4918-4923 [PubMed PMID: 29164568]

Mirza B, Ijaz L, Saleem M, Sharif M, Sheikh A. Cystic hygroma: an overview. Journal of cutaneous and aesthetic surgery. 2010 Sep:3(3):139-44. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.74488. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21430825]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBloom DC, Perkins JA, Manning SC. Management of lymphatic malformations. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2004 Dec:12(6):500-4 [PubMed PMID: 15548907]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVeeraraghavan G,Denny C,Lingappa A, Cystic hygroma in an adult; a case report. The Libyan journal of medicine. 2009 Dec 1; [PubMed PMID: 21483540]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuruprasad Y, Chauhan DS. Cervical cystic hygroma. Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery. 2012 Sep:11(3):333-6. doi: 10.1007/s12663-010-0149-x. Epub 2011 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 23997487]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen YN, Chen CP, Lin CJ, Chen SW. Prenatal Ultrasound Evaluation and Outcome of Pregnancy with Fetal Cystic Hygromas and Lymphangiomas. Journal of medical ultrasound. 2017 Jan-Mar:25(1):12-15. doi: 10.1016/j.jmu.2017.02.001. Epub 2017 Apr 17 [PubMed PMID: 30065449]

Kumar N, Kohli M, Pandey S, Tulsi SP. Cystic hygroma. National journal of maxillofacial surgery. 2010 Jan:1(1):81-5. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.69152. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22442559]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGallagher PG, Mahoney MJ, Gosche JR. Cystic hygroma in the fetus and newborn. Seminars in perinatology. 1999 Aug:23(4):341-56 [PubMed PMID: 10475547]

Kahn A, Blum D, Hoffman A, Hamoir M, Moulin D, Spehl M, Montauk L. Obstructive sleep apnea induced by a parapharyngeal cystic hygroma in an infant. Sleep. 1985 Dec:8(4):363-6 [PubMed PMID: 3880177]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBahl S, Shah V, Anchlia S, Vyas S. Adult-onset cystic hygroma: A case report of rare entity. Indian journal of dentistry. 2016 Jan-Mar:7(1):51-4. doi: 10.4103/0975-962X.179374. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27134456]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKamath BS, Chatterjee AS, Chandorkar I, Bhanushali H. GIANT RECURRENT CYSTIC HYGROMA: A CASE REPORT. Journal of the West African College of Surgeons. 2014 Apr-Jun:4(2):100-11 [PubMed PMID: 26587526]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKocher HM, Vijaykumar T, Koti RS, Bapat RD. Lymphangioma of the chest wall. Journal of postgraduate medicine. 1995 Jul-Sep:41(3):89-90 [PubMed PMID: 10707725]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHa J, Yu YC, Lannigan F. A review of the management of lymphangiomas. Current pediatric reviews. 2014:10(3):238-48 [PubMed PMID: 25088344]