Introduction

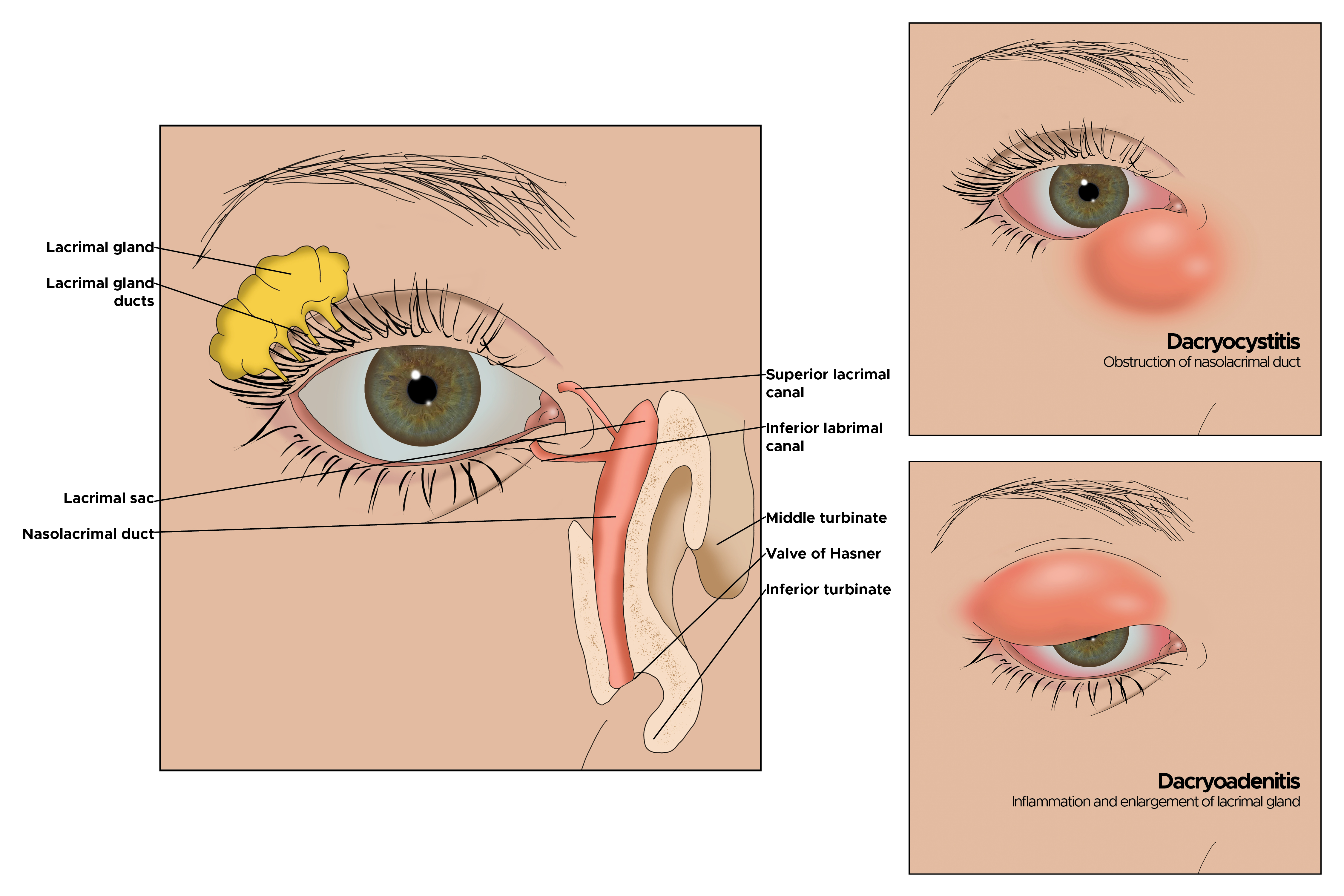

Dacryoadenitis refers to inflammation of the lacrimal gland and may be unilateral or bilateral. The lacrimal gland is located superotemporally to the globe, within the extraconal orbital fat. The gland consists of palpebral and orbital lobes, which are separated by the lateral horn of the levator aponeurosis. Inflammation of the gland can be due to infectious or inflammatory sources but may be idiopathic. Viral dacryoadenitis is self-resolving, while bacterial sources may require antibiotic administration. Inflammatory causes may respond to steroids, or demonstrate a chronic relapsing course requiring long-term treatment to maintain remission.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Lacrimal gland inflammation can be acute or chronic. Cases of acute dacryoadenitis are frequently infectious and are typically unilateral.[1] Infection most commonly ascends from the conjunctiva, but also may be from the skin, penetrating trauma, or seeding in the setting of bacteremia. The causative pathogens are more often viral than bacterial, particularly in children and young adults. Viruses typically result in acute nonsuppurative dacryoadenitis. The most common viral etiology is Epstein-Barr virus; others include adenovirus, mumps, herpes simplex, and herpes zoster.[2] Bacterial sources tend to induce suppuration; while the primary bacterial pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus, others include Streptococcus pneumoniae and gram-negative rods. Rarely, fungal sources such as Histoplasma, Blastomyces, or Nocardia may be found. Chronic infectious dacryoadenitis is uncommon, with most cases attributed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis.[3]

More often chronic cases of dacryoadenitis are inflammatory. Associated conditions include Sjogren syndrome, sarcoidosis, Crohn disease, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Despite a new understanding of and testing for these conditions, a large portion of inflammatory cases remains idiopathic. There has also been academic interest in the recently described immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-related dacryoadenitis, which accounts for 23% to 35% of reports of previously idiopathic orbital inflammation.[4][5]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of dacryoadenitis is not reported, but it is less common than dacryocystitis (inflammation or infection of the lacrimal sac). Acute dacryoadenitis is most commonly identified in children and young adults.[1] Dacryoadenitis that is associated with an autoimmune disease appears to be more prevalent in women than in men, consistent with the gender predilection in systemic autoimmune disease overall.[6]

Histopathology

Nonspecific inflammation of the lacrimal gland may demonstrate several patterns on histopathology. Inflammation may be composed of predominantly lymphocytic infiltration, or mixed with neutrophilic infiltration. The pattern of infiltration may be focal, diffuse, or perivascular. Fibrosis and/or acinar destruction may be present.[6] When associated with sarcoidosis, non-necrotizing granulomas of epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells may be observed. IgG4-related dacryoadenitis demonstrates lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and may develop interlobular fibrosis.[7] Immunohistochemical staining can indicate the increased number of IgG4-positive plasma cells.[8]

History and Physical

Acute dacryoadenitis frequently presents with erythema and tenderness over the superotemporal orbit, with enlargement of the gland causing the lateral portion of the eyelid to fall, creating a characteristic S-shaped curve of the eyelid margin. There can also be associated suppurative discharge from lacrimal ducts, pouting of the lacrimal ductules, conjunctival chemosis, and swollen preauricular and cervical lymph nodes. Fever and malaise may be present. Inflammatory causes of dacryoadenitis may present subacutely with typically painless swelling of the lacrimal glands and may be bilateral.

Evaluation

Acute lacrimal gland swelling that presents in association with a viral illness does not require biopsy or comprehensive laboratory evaluation. However, if there are atypical features or if the swelling does not resolve with treatment, an additional workup is merited. Occurrence in older adults, bilateral presentation, and systemic symptoms may suggest a malignant or systemic autoimmune process, in which case additional workup is strongly advisable.

Laboratory evaluation for the etiology of dacryoadenitis may include a complete blood count, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA). Angiotensin-converting enzyme is an unreliable marker of sarcoidosis. Testing for anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies in cases of suspected Sjogren syndrome is reasonable, although the yield is low.

Radiologic imaging with CT or MRI reveals diffuse, potentially oblong, enlargement of the lacrimal gland. Imaging of acute dacryoadenitis may reveal adjacent lateral rectus myositis, periscleritis, or scleritis.[9] Chronic inflammatory conditions are not associated with scleral enhancement.

Lacrimal gland biopsy may be of use in cases of dacryoadenitis that are atypical, of unclear etiology, or fail to respond appropriately to therapy. In a review of biopsy performed on 60 cases of lacrimal gland inflammation of unknown cause, 61.7% were found to have specific histopathology, and 38% connected to systemic diseases.[6] As steroids can alter the histologic demonstration, it is advisable to avoid systemic steroids before the biopsy when possible. A biopsy is generally performed via a transcutaneous approach, sampling the orbital lobe to avoid the tear ducts that drain through the palpebral lobe to the temporal conjunctival fornix. Submitted tissue samples may be fixed in formalin while fresh tissue is required for flow cytometry. When performing a biopsy of a lacrimal gland with unknown etiology, always contact your laboratory to ensure they are aware that you will be sending a fresh sample and one in formalin. Some laboratories have specific requirements of how to transport the specimen, especially for flow cytometry.

Treatment / Management

Acute viral dacryoadenitis is typically self-resolving within 4 to 6 weeks. The benefit of oral antiviral medications is uncertain. Bacterial dacryoadenitis requires systemic antibiotic therapy, and coverage for methicillin-resistant S. aureus is prudent. When purulence is present, obtaining cultures of the discharge can guide antibiotic therapy. Abscess formation may necessitate surgical drainage.

Corticosteroids will induce shrinkage of an enlarged lacrimal gland from almost all sources of dacryoadenitis; therefore, a trial of steroids for diagnostic purposes is not warranted. One study suggests that idiopathic dacryoadenitis may respond to surgical debulking, with a low relapse rate.[10] Refractory cases of inflammatory dacryoadenitis may benefit from orbital radiotherapy, methotrexate, or rituximab. IgG4-related disease has a high rate of remission with rituximab, but this effect may be temporary.[11](B2)

Management of IgG4-related dacryoadenitis is still debated. An initial trial of corticosteroids is reasonable. Immunosuppression is only rarely necessary. There are reports suggesting that sclerosing dacryoadenitis that is associated with IgG4 can go on to develop lymphoma.[12](B2)

In patients with dacryoadenitis who respond to treatment but the lacrimal mass does not resolve by 3 months, a lacrimal gland biopsy after appropriate scanning is necessary.[13]

Differential Diagnosis

When focal swelling of the lacrimal gland is present, particularly in an older patient with an indolent course, it is important to exclude malignancy. Lymphomatous lesions can infiltrate the lacrimal gland. Such processes fall on a spectrum from reactive lymphoid hyperplasia through atypical lymphoid hyperplasia to malignant lymphoma. Benign and malignant lymphoid tumors cause diffuse enlargement of both lacrimal lobes on imaging. Epithelial tumors of the lacrimal gland may have a similar clinical presentation, including benign mixed tumors, adenoid cystic carcinoma, mixed malignant carcinoma, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Of etiologies that induce enlargement of the lacrimal gland, approximately 50% are infectious or inflammatory, 25% are lymphoid tumors, and 25% are salivary tumors.[14]

Thyroid eye disease (TED) may sometimes resemble dacryoadenitis, presenting with diplopia from restrictive inflammation of the extraocular muscles. Typically, TED results in lid retraction rather than mild ptosis as is seen in dacryoadenitis.

Other infectious conditions that can cause periorbital swelling, erythema, and pain must be considered, such as preseptal or orbital cellulitis. Focal swelling of the upper eyelid may be due to chalazion or hordeolum, neither of which is associated with true lacrimal gland enlargement.

Prognosis

Infectious dacryoadenitis may require antibiotics but typically resolves without complications. Inflammatory dacryoadenitis is more resistant to therapy and depends on the underlying systemic process if present. These cases may require an extended steroid taper, chronic immunomodulatory therapy, or surgical debulking.[10] As with any non-specific inflammation in the orbit, if there is a recurrence or failure to resolve, a biopsy or repeat biopsy is necessary.

Complications

While complications from infectious dacryoadenitis are rare, a lacrimal gland abscess may develop, or the infection may lead to preseptal or orbital cellulitis.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with infectious dacryoadenitis should be counseled that the condition will typically resolve and may require antibiotic therapy. Monitoring for vision changes, pain with eye movements, or suppuration can be important to detect complications such as orbital cellulitis or abscess formation. When dacryoadenitis is connected to an autoimmune process, patients should be educated on the disease and potential systemic manifestations, as well as the potential need for an extended taper of steroids or long-term immunomodulatory therapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Dacryoadenitis is an uncommon disease process, and thus communication between health care providers can facilitate appropriate diagnosis and treatment of patients with the disease. An oculoplastic surgeon may be needed to perform a lacrimal gland biopsy to aid in diagnosis. In cases of inflammatory dacryoadenitis that recur after completion of a steroid taper, collaboration with a rheumatologist to consider initiation of immunomodulatory therapy is frequently beneficial. Similarly, coordination with rheumatology and internal medicine is advisable when patients with dacryoadenitis report extraocular symptoms that may indicate a systemic disease process. (Level V) an interprofessional team approach involving plastic specialty certified nurses and specialist physicians providing evaluation and follow up will result in the best outcomes. [Level V]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mafee MF,Haik BG, Lacrimal gland and fossa lesions: role of computed tomography. Radiologic clinics of North America. 1987 Jul [PubMed PMID: 3299475]

Rhem MN,Wilhelmus KR,Jones DB, Epstein-Barr virus dacryoadenitis. American journal of ophthalmology. 2000 Mar [PubMed PMID: 10704555]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMadge SN,Prabhakaran VC,Shome D,Kim U,Honavar S,Selva D, Orbital tuberculosis: a review of the literature. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2008 [PubMed PMID: 18716964]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAndrew NH,Sladden N,Kearney DJ,Selva D, An analysis of IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) among idiopathic orbital inflammations and benign lymphoid hyperplasias using two consensus-based diagnostic criteria for IgG4-RD. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2015 Mar [PubMed PMID: 25185258]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDeschamps R,Deschamps L,Depaz R,Coffin-Pichonnet S,Belange G,Jacomet PV,Vignal C,Benillouche P,Herdan ML,Putterman M,Couvelard A,Gout O,Galatoire O, High prevalence of IgG4-related lymphoplasmacytic infiltrative disorder in 25 patients with orbital inflammation: a retrospective case series. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2013 Aug [PubMed PMID: 23759440]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLuemsamran P, Rootman J, White VA, Nassiri N, Heran MKS. The role of biopsy in lacrimal gland inflammation: A clinicopathologic study. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2017 Dec:36(6):411-418. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2017.1352608. Epub 2017 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 28816552]

McNab AA,McKelvie P, IgG4-Related Ophthalmic Disease. Part II: Clinical Aspects. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015 May-Jun [PubMed PMID: 25564258]

Go H,Kim JE,Kim YA,Chung HK,Khwarg SI,Kim CW,Jeon YK, Ocular adnexal IgG4-related disease: comparative analysis with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and other chronic inflammatory conditions. Histopathology. 2012 Jan [PubMed PMID: 22211288]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAndrew NH,Kearney D,Sladden N,McKelvie P,Wu A,Sun MT,McNab A,Selva D, Idiopathic Dacryoadenitis: Clinical Features, Histopathology, and Treatment Outcomes. American journal of ophthalmology. 2016 Mar [PubMed PMID: 26701269]

Mombaerts I,Cameron JD,Chanlalit W,Garrity JA, Surgical debulking for idiopathic dacryoadenitis: a diagnosis and a cure. Ophthalmology. 2014 Feb [PubMed PMID: 24572677]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEbbo M,Patient M,Grados A,Groh M,Desblaches J,Hachulla E,Saadoun D,Audia S,Rigolet A,Terrier B,Perlat A,Guillaud C,Renou F,Bernit E,Costedoat-Chalumeau N,Harlé JR,Schleinitz N, Ophthalmic manifestations in IgG4-related disease: Clinical presentation and response to treatment in a French case-series. Medicine. 2017 Mar [PubMed PMID: 28272212]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCheuk W,Yuen HK,Chan AC,Shih LY,Kuo TT,Ma MW,Lo YF,Chan WK,Chan JK, Ocular adnexal lymphoma associated with IgG4+ chronic sclerosing dacryoadenitis: a previously undescribed complication of IgG4-related sclerosing disease. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2008 Aug [PubMed PMID: 18580683]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRose GE, A personal view: probability in medicine, levels of (Un)certainty, and the diagnosis of orbital disease (with particular reference to orbital "pseudotumor"). Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2007 Dec [PubMed PMID: 18071128]

Gao Y,Moonis G,Cunnane ME,Eisenberg RL, Lacrimal gland masses. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2013 Sep [PubMed PMID: 23971467]