Introduction

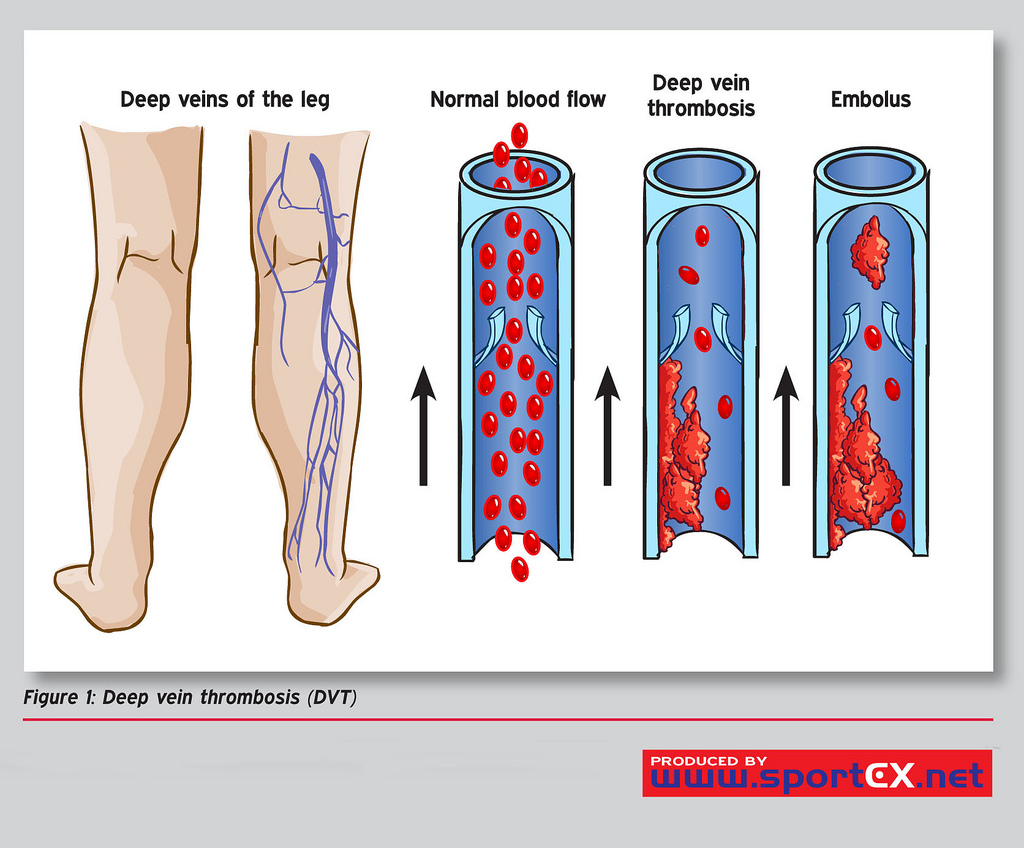

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, and sequelae range from venous stasis to pulmonary embolism (PE). DVT occurs when a thrombus (thrombus) forms in 1 of the body's deep veins. See Image. Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT).

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Virchow's triad of venous stasis or turbulence, coagulopathy, and endothelial injury highlight the major risk factors for developing a DVT. Other known and common risk factors include malignancy, recent surgery, immobilization, estrogen therapy, especially when combined with tobacco abuse, a history of previous DVT or PE, and strong family history.[1][2][3][4][3]

Epidemiology

DVT is a common problem in primary care, acute care, and inpatient settings. It is not clear what the actual incidence is, but DVT is found in about 80 out of 100,000 cases. One out of 20 people develops a DVT sometime during their lifetime. DVTs account for approximately 600,000 hospitalizations per year in the United States. DVTs occur more commonly in those older than 40 years old. There is an increased incidence in the male and African American populations.

Pathophysiology

Venous stasis, endothelial damage, or inflammation are typically present and lead to a hypercoagulable state. Activation of the clotting cascade and aggregation of platelets and blood cells occurs simultaneously to form a thrombus. The thrombus can cause complete or partial vein occlusion, leading to venous stasis, lymphedema, and possibly ischemia to surrounding tissue. A DVT can propagate and lead to PE.

History and Physical

Specific historical features that assist in the diagnosis of a DVT are those related to DVT risk factors and include a history of cancer, exogenous estrogen therapy, recent surgery, smoking tobacco, previous history of DVT, immobility, age, history of a hypercoagulable state, and other comorbidities. Patients often present with a chief complaint of unilateral leg swelling and discomfort. Be mindful to ask about symptoms related to a PE, such as chest pain, shortness of breath, and syncope. The physical exam most commonly demonstrates unilateral extremity swelling, warmth and discomfort over the vein, and, perhaps, a palpable "cord" where the DVT is located.

Evaluation

Clinical decision rules such as the Pulmonary Embolism Rule-Out Criteria (PERC) and the Wells Criteria should be employed when the patient presents with a possible DVT. Risk stratification is crucial in deciding diagnostic and management options. Patients who meet PERC criteria may need no further testing. In contrast, those who do not meet PERC criteria and are low probability based on the Wells Criteria may be candidates for rule-out with a D-dimer. The D-dimer test is sensitive but not specific. It should be used selectively in low-probability patients who do not have other confounding diagnoses that could produce a false positive test. The test should also be used cautiously, with different cut-off values for the elderly.[5][6][7][8]

Imaging modalities for DVT evaluation include diagnostic ultrasound, vascular studies, CT venograms, and point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS). The POCUS exam is described below.

Rapid diagnosis or rule-out by the emergency provider can expedite necessary treatment, reduce the length of stay, and is particularly useful where access to 24-hour ultrasound is unavailable. There is evidence that emergency practitioners can perform a 2-point compression exam at the 2 highest probability sites for identifying a DVT: femoral and popliteal veins. However, recent literature suggests a 2-region approach where clinicians do serial compression testing, which may greatly improve diagnostic sensitivity without increasing diagnostic time. This point-of-care ultrasound exam should be used with other clinical decision rules and is perhaps most useful in those patients with high and low pre-test probability.

With the patient supine in the frog-leg position, approximately 20 to 30 degrees of reverse Trendelenburg is applied to increase venous distention. Place the high-frequency linear transducer (5 to 10 MHz) in the transverse plane at the anatomical location of the inguinal ligament. The common femoral vein can be visualized just distal to the inguinal ligament. Apply direct pressure to the vein. The complete collapse of the vein indicates there is no presence of a DVT. Continue distally along the femoral vein to where the greater saphenous and deep femoral veins deviate from the common femoral veins. Compression of all venous structures at these levels rules out a proximal DVT.

Next, proceed to the popliteal region. Laterally rotate the leg, flex the knee, and place the high-frequency transducer transversely in the popliteal fossa. The popliteal vein typically resides just anterior to the popliteal artery. Apply a compressive force once again and observe for complete compression. Compress the proximal and distal areas to the popliteal fossa to complete the 2-region technique. See Video. Popliteal Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) With Partial Color Flow.

If DVT studies are negative, repeat testing may be required in 1 to 2 weeks to rule out a propagating calf DVT further. Alternatively, sending a D-dimer test may be adequate in certain patient populations. Typical laboratory tests also should be sent to evaluate for coagulation status, blood count, and renal function.[9][10]

Treatment / Management

There are many options available to manage DVT. The first decision that should be made is whether the patient requires hospital admission or can be discharged on anticoagulation. This complex decision depends on many factors, including patient adherence to medication, insurance issues, the reliability of follow-up, renal function, comorbidities, concomitant medications, the risk of falling, and how ill the patient appears. The traditional treatment option is to use heparin or low-molecular-weight heparin and bridge to warfarin therapy. This often requires hospital admission, but it may be managed as an outpatient in some healthcare settings. New anticoagulants such as direct antithrombin inhibitors are also options, but the use of these medications must be made on an individual basis.

Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters have been used historically to avoid the propagation of DVTs in the pulmonary artery. Based on current literature, it is unclear if IVC filters prevent PEs, and therefore, they are falling out of favor. However, they may still be indicated in specific clinical situations.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremity include the following:

- Baker cyst imaging

- Budd-Chiari syndrome imaging

- Cellulitis

- Dependent oedema

- Heart failure

- Hepatic disease

- Pulmonary embolism

- Renal failure

- Septic thrombophlebitis

- Nephritic syndrome

Pearls and Other Issues

The 2-region ultrasound examination commonly misses calf DVTs. Complete compression of the veins is the only measure that rules out DVTs. Doppler and color may be used but are not necessary for this evaluation. This safe and rapid exam does not lead to DVT propagation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Deep vein thrombosis is a common occurrence in hospitalized patients. The condition has no specific signs and symptoms, and to prevent high morbidity and mortality, it is best managed by an interprofessional team that consists of a nurse practitioner, hematologist, internist, and pharmacist. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are key. There are many treatment options today, but some anticoagulation therapy is required. The condition is best treated by prophylaxis with unfractionated heparin or LMWH. Compression stockings and early mobility after surgery are essential. For those treated promptly, the outlook is good, but postphlebitic syndrome is known to occur in a significant number of patients.[11][12]

Media

(Click Video to Play)

Popliteal Deep Vein Thrombosis With Partial Color Flow

Contributed by M Schick, DO

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Brandão GMS, Cândido RCF, Rollo HA, Sobreira ML, Junqueira DR. Direct oral anticoagulants for treatment of deep vein thrombosis: overview of systematic reviews. Jornal vascular brasileiro. 2018 Oct-Dec:17(4):310-317. doi: 10.1590/1677-5449.005518. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30787949]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJara-Palomares L, van Es N, Praena-Fernandez JM, Le Gal G, Otten HM, Robin P, Piccioli A, Lecumberri R, Religa P, Rieu V, Rondina M, Beckers M, Prandoni P, Salaun PY, Di Nisio M, Bossuyt PM, Kraaijpoel N, Büller HR, Carrier M. Relationship between type of unprovoked venous thromboembolism and cancer location: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Thrombosis research. 2019 Apr:176():79-84. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.02.011. Epub 2019 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 30780008]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceXu S, Chen JY, Zheng Q, Lo NN, Chia SL, Tay KJD, Pang HN, Shi L, Chan ESY, Yeo SJ. The safest and most efficacious route of tranexamic acid administration in total joint arthroplasty: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Thrombosis research. 2019 Apr:176():61-66. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.02.006. Epub 2019 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 30776688]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLi J, Zhang F, Liang C, Ye Z, Chen S, Cheng J. The Diagnostic Efficacy of Age-Adjusted D-Dimer Cutoff Value and Pretest Probability Scores for Deep Venous Thrombosis. Clinical and applied thrombosis/hemostasis : official journal of the International Academy of Clinical and Applied Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 2019 Jan-Dec:25():1076029619826317. doi: 10.1177/1076029619826317. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30754991]

Tran HA, Gibbs H, Merriman E, Curnow JL, Young L, Bennett A, Tan CW, Chunilal SD, Ward CM, Baker R, Nandurkar H. New guidelines from the Thrombosis and Haemostasis Society of Australia and New Zealand for the diagnosis and management of venous thromboembolism. The Medical journal of Australia. 2019 Mar:210(5):227-235. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50004. Epub 2019 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 30739331]

Coolidge W. Development of a Pharmacologic Venous Thromboembolism Protocol for Trauma Patients. South Dakota medicine : the journal of the South Dakota State Medical Association. 2018 Oct:71(10):438-444 [PubMed PMID: 30731517]

Alyea E, Gaston T, Austin LS, Wowkanech C, Cypel B, Pontes M, Williams G. The Effectiveness of Aspirin for Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis for Patients Undergoing Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Orthopedics. 2019 Mar 1:42(2):e187-e192. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20181227-05. Epub 2019 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 30602049]

Kim JS. Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis after Total Hip Arthroplasty in Asian Patients. Hip & pelvis. 2018 Dec:30(4):197-201. doi: 10.5371/hp.2018.30.4.197. Epub 2018 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 30534537]

Ohmori H, Kanaoka Y, Yamasaki M, Takesue H, Sumimoto R. Prevalence and Characteristic Features of Deep Venous Thrombosis in Patients with Severe Motor and Intellectual Disabilities. Annals of vascular diseases. 2018 Sep 25:11(3):281-285. doi: 10.3400/avd.oa.18-00028. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30402176]

Tritschler T, Kraaijpoel N, Le Gal G, Wells PS. Venous Thromboembolism: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2018 Oct 16:320(15):1583-1594. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14346. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30326130]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLópez-Núñez JJ, Trujillo-Santos J, Monreal M. Management of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH. 2018 Dec:16(12):2391-2396. doi: 10.1111/jth.14305. Epub 2018 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 30246407]

Milinis K, Shalhoub J, Coupland AP, Salciccioli JD, Thapar A, Davies AH. The effectiveness of graduated compression stockings for prevention of venous thromboembolism in orthopedic and abdominal surgery patients requiring extended pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. Journal of vascular surgery. Venous and lymphatic disorders. 2018 Nov:6(6):766-777.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvsv.2018.05.020. Epub 2018 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 30126797]