Introduction

The diaphragm is a thin, dome-shaped muscular structure that functions as a respiratory pump and is the primary muscle for inspiration.[1] Elevated hemidiaphragm occurs when one side of the diaphragm becomes weak from muscular disease or loss of innervation due to phrenic nerve injury. Patients may present with difficulty breathing, but more commonly elevated hemidiaphragm is found on imaging as an incidental finding, and patients are asymptomatic.

The phrenic nerve runs in the fascia over the anterior scalene muscle. An anesthesiologist commonly performs interscalene blocks for shoulder surgery, such as a rotator cuff repair, humeral fracture, total shoulder replacement, and other arm surgery. phrenic nerve paralysis is a known complication from the interscalene block. It has been observed in many case reports and series in both anesthesia and neurosurgical literature, but only a single case report in the emergency medicine literature.

The diaphragm is the primary muscle for inspiration along with secondary muscles such as the sternocleidomastoid, external intercostals, and scalene muscles. During inspiration, the diaphragm flattens pulling air into the lungs, whereas during expiration, the diaphragm relaxes, allowing air to flow out of the lungs passively. As the diaphragm flattens during inspiration subatmospheric, negative pressure is created within the thoracic cavity that overcomes atmospheric pressure. This forms a vacuum that facilitates the movement of air into the lungs. Also, as the diaphragm contracts, the floor of the thoracic cavity moves downward, and the walls move outward. This causes inflation of the lungs and allows for gas exchange to occur. As the diaphragm relaxes, the tension on the chest wall muscles decreases, causing the muscles to recoil and passively push the air out during expiration.

The diaphragm has three points of origin, creating a C shape that culminates in a stable, dense fibrous center tendon. The sternal group of muscle fibers is attached to the posterior aspect of the xiphoid process. The costal group of muscle fibers originates from the inner surface of seven to twelfth ribs. The lumbar group of muscular fibers arises from the medial and lateral arcuate ligaments and anterior longitudinal ligament, and lumbar vertebral bodies of L2-L3. There are three openings in the diaphragm, allowing structures to pass between the thoracic and abdominal cavity. The esophageal hiatus through which the esophagus and vagus nerve pass, the aortic hiatus through which the aorta, azygos vein and thoracic duct pass, and the caval hiatus through which the inferior vena cava passes.

The diaphragm anatomically separates the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity,[1] making the diaphragm the base of the thoracic cavity and the apex of the abdominal cavity. The diaphragm is separated into the right and left half. Each side has it's own blood supply from the inferior and superior phrenic arteries arising directly from the aorta, subcostal and intercostal arteries. Phrenic veins drain blood from the diaphragm directly into the inferior vena cava.

The diaphragm is innervated by the ipsilateral phrenic nerve that arises from the cervical nerve roots of C3-C5.[2] The phrenic nerve emerges through the anterior scalene muscle on either side of the neck and courses posteriorly to the subclavian vein. Both phrenic nerves enter into the thoracic cavity through the thoracic aperture. In the thoracic cavity, the right and left phrenic nerves follow different paths. The right phrenic nerve descends anteriorly over the right atrium of the heart and exits through the inferior vena cava opening to innervate the inferior surface of the hemidiaphragm. The left phrenic nerve crosses the aortic arch and pericardium overlying the left ventricle until it pierces through the diaphragm to innervate the inferior surface of the left hemidiaphragm. Sensory innervation of the diaphragm is from the intercostal nerves 6-11.

Elevated Hemidiaphragm is a condition where one portion of the diaphragm is higher than the other. Often elevated hemidiaphragm is asymptomatic and visualized as an incidental finding on radiologic studies like chest X-ray or chest CT (computed tomography). Patients are typically asymptomatic due to the compensation and recruitment of other inspiratory muscles, and often the healthy hemidiaphragm compensates to maintain the pressure gradient required for adequate gas exchange. However, evidence suggests that the function of the contralateral, healthy hemidiaphragm may be impacted by lower abdominal pressure.[3][4]

In severe cases of unilateral hemidiaphragm paralysis, patients may lose their inspiratory capacity, which can impair the ability of the heart to pump efficiently. Under normal circumstances, the intrathoracic pressure and contraction of the diaphragm overcome the force of gravity and propel blood into the right atrium from the inferior vena cava (IVC). When the pressure gradient cannot be maintained, the right atrium will collapse, and the patient may present as though they have cardiac tamponade.[5] Accurate diagnosis, treatment, and management of elevated hemidiaphragm are essential in patients presenting with dyspnea and multi-organ involvement.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The causes of elevated hemidiaphragm can be divided into three categories: above the diaphragm, at the diaphragm, and below the diaphragm.

Above the Diaphragm

The phrenic nerve innervates the diaphragm. Any injury, trauma, or disease affecting the phrenic nerve will lead to weakening or paralysis of the diaphragm, also called diaphragmatic palsy. Damage to the phrenic nerve may originate from the brain, spine, spinal cord, trauma, autoimmune disease, or can be from an unknown cause.[6] Neuromuscular disorders like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), multiple sclerosis (MS), myasthenia gravis, or muscular dystrophy can impair the phrenic nerve and or musculature of the diaphragm leading to diaphragmatic weakness. However, this is more commonly seen with bilateral diaphragm palsy and, ultimately, paralysis.

In the brain, a middle cerebral artery (MCA) stroke will cause paralysis of the contralateral side, potentially leading to elevated hemidiaphragm on the opposite side of the occlusion of MCA. The phrenic nerve originates from the cervical roots of C3-C5; therefore, injury to the brachial plexus can impair the proper function of the phrenic nerve. Isolated brachial plexus injury is typically seen as a congenital defect and from direct trauma. However, many pathological processes or trauma from the neck down to the subphrenic region may cause weakness in the phrenic nerve that can cause ipsilateral elevated hemidiaphragm. Elevated hemidiaphragm can result from neck surgery, trauma, compression fractures to the cervical spine, bronchial artery embolization, or cervical spondylosis.[7][8] Injury to the phrenic nerve causing phrenic nerve palsy and temporary or permanent paralysis is also seen when anesthesiologist performs interscalene blocks for procedures in shoulder injuries such as rotator cuff repair, humeral fracture, shoulder replacement surgery.[9]

Unilateral injury to the phrenic nerve is a common complication of cardiac surgery. The left phrenic nerve is often injured when the heart is cooled during the procedure, and if the phrenic nerve is stretched during surgery. The damage to the left phrenic nerve leads to elevated left hemidiaphragm.[10]

Lung pathologies such as pneumothorax, atelectasis, partial or complete pneumonectomy, and or congenital defects like pulmonary hypoplasia or diaphragmatic eventration may result in elevated hemidiaphragm usually on the ipsilateral side of pathology. In rare cases, chronic coughing in asthmatics has led to a spontaneous diaphragmatic hernia, which caused an elevated right hemidiaphragm.[11]

Diaphragm

Congenital defect leading to partial or incomplete muscularization of the diaphragm causing an abnormal contour of the diaphragm in that region is referred to as diaphragmatic eventration. Most of the congenital malformations are in the right hemidiaphragm and, more specifically, in the anteromedial portion. These defective areas are covered with a thin membrane in place of healthy muscle, which can appear as an elevated hemidiaphragm on imaging studies.

Elevated hemidiaphragm can also occur when there is direct injury to the diaphragm from penetrating trauma such as a stab wound.

Below the Diaphragm

Liver pathologies are more commonly linked to right elevated hemidiaphragm. Enlarged liver, whether homogenous hepatomegaly or secondary to an abscess or hepatic tumor, can push up the right hemidiaphragm. Distention of the stomach, abdominal tumors, distended abdomen, subphrenic abscess, splenomegaly, or colon malrotation can present as elevated left hemidiaphragm. Elevated hemidiaphragm may occur secondary to pneumoperitoneum from a ruptured stomach or colon where free air becomes trapped under the diaphragm.

In rare cases, the colon wraps above the liver; on radiographic images, this appears as air below the right diaphragm called Chilaiditi sign. Most patients are asymptomatic, but in rare situations, the portion of intestine lopped above the liver can become obstructed, causing Chilaiditi syndrome.

Epidemiology

Elevated hemidiaphragm is more common than bilateral diaphragm weakness. The causes of both elevated hemidiaphragm and bilateral diaphragm paralysis are similar, with the significant difference being the rate of incidence. The exact frequency of diaphragmatic disorders is not known and is difficult to estimate. It is likely that diaphragmatic disorders are under-diagnosed due to subtle clinical findings and varying etiologies. However, the incidence of many specific causes of diaphragmatic disorders is known.

Coronary artery bypass grafting surgery is associated with lesions of the phrenic nerves resulting in postoperative diaphragmatic paralysis, with a reported incidence varying from 1% to 5%, with some reports as high as 60%. Internal mammary artery harvesting and the use of frozen slurry during cardiac surgery increase the risk of phrenic nerve injury.[12][13][14] Up to 25% of patients with Guillain-Barre disease will develop diaphragmatic weakness requiring mechanical ventilation.[15]

Pathophysiology

Almost 90% of cases of elevated hemidiaphragm are asymptomatic.[3] In severe cases or with bilateral phrenic nerve paralysis causing diaphragmatic palsy, patients will present with dyspnea or orthopnea.[16] Pulmonary function test results will resemble that of restrictive lung disease. A restrictive profile is seen when the lungs are smaller or stiffer and occur in conditions where the lungs cannot fully expand. The weakened hemidiaphragm initially moves paradoxically during inspiration, which can increase the work of inspiration, causing dyspnea.

Over time, compliance of the muscle decreases, and the increased work of breathing subsides. In severe cases where the pressure gradient is not maintained, the heart may also be affected, causing dyspnea, tachypnea, and jugular vein distention. In this situation, the patient will require immediate life-saving intervention, such as intubation or surgery.

History and Physical

A proper history and physical is vital in determining the cause of elevated hemidiaphragm. Recent pulmonary infection, neuromuscular diseases, autoimmune disease, congenital malformations, and direct trauma should all be considered. In cases where patients present with severe pulmonary distress and a proper history cannot be obtained, imaging studies will help rule out differential causes of elevated hemidiaphragm. Most patients with unilateral diaphragm dysfunction have no symptoms, and they are generally found with the incidental elevation of a hemidiaphragm on chest imaging.[12] Symptoms include mild exertional dyspnea, generalized muscle fatigue, chest wall pain, and resting dyspnea while lying with the paralyzed side down or when the abdomen is submerged underwater. Symptoms are more severe in patients with concomitant lung disease.

Physical examination findings in case of unilateral diaphragm paralysis include decreased breath sounds, dullness on the lower chest on percussion of the involved side, paradoxical abdominal wall retraction during inspiration, hypoxemia secondary to atelectasis, generalized or focal neurological deficit.

Evaluation

Elevated hemidiaphragm is usually asymptomatic, and 90% of cases are diagnosed incidentally on imaging studies. In emergencies, the quickest and most reliable test to assess diaphragm function is an ultrasound that can be performed at the bedside.

1.Imaging Studies to Diagnose Elevated Hemidiaphragm

Fluoroscopy:

This was the test of choice. Have the patient perform sniff maneuvers with a fluoroscopic examination of the diaphragm. In patients with elevated hemidiaphragm, the weakened hemidiaphragm will move paradoxically during inspiration. The fluoroscopic examination involves ionizing-radiation, which may increase cancer risk.

Ultrasound:

This testing modality is fast, non-invasive, portable, and safe since there is no radiation. Therefore, ultrasound is now the better choice for assessing diaphragmatic function. The diaphragm is visualized best in M mode and appears as a thick line. During inspiration, when the diaphragm contracts, it is about 20% thicker than at the end of quiet respiration. Diaphragmatic weakness is suggested if the thickness does not increase by 20% or if the diaphragm thickness is <15mm.[17] Diaphragmatic paralysis leads to paradoxical movement of the diaphragm during inspiration.

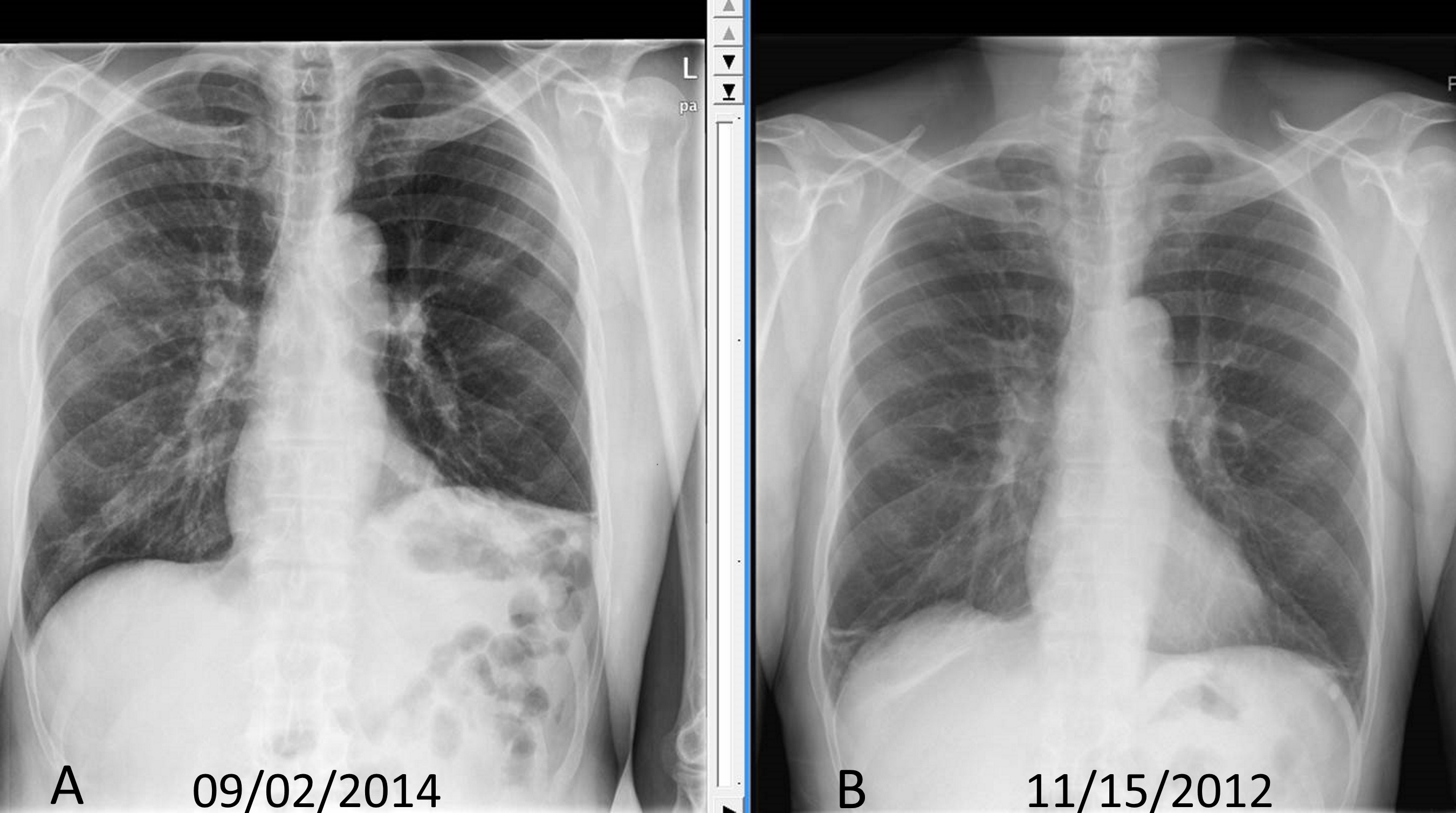

Chest X-Ray:

To best see the diaphragm, the patient should take a deep breath, be standing upright. If elevated hemidiaphragm is present, the PA view will show either side of the diaphragm is more than 2cm higher than the other side. Chilaiditi sign can be visualized on a chest x-ray, identifying bowel loops over the liver.

Chest and Abdomen Computed Tomography (CT):

All patients suspected of diaphragmatic injury should undergo a chest CT. It is vital to diagnose, identify, and rule out the causes of elevated hemidiaphragm. A chest and abdomen CT will help identify any masses, thoracic, and or abdominal pathologies that explain the reason for elevated hemidiaphragm.

2.Non-imaging Tests

EKG:

Rules out acute coronary syndrome and evaluates whether the heart is functioning properly.

Echocardiogram:

Evaluates the ability of the heart to pump and function properly.

Pulmonary Function Tests (PFT):

The diaphragm is the primary muscle for inspiration since it accounts for 80% of the power required for respiration.[3] Without a properly functioning diaphragm, the lungs cannot expand sufficiently and thus yield a restrictive lung disease pattern. An elevated hemidiaphragm will show a reduced forced vital capacity (FVC) of 30% of the standard predicted value. With bilateral diaphragm paralysis, the FVC may decrease by 75% of the expected value.

Electrophysiological studies- Aid in determining whether the etiology of diaphragmatic dysfunction is muscular or neurological.

3.Lab Tests

Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis:

Determines whether there is adequate gas exchange.

Treatment / Management

The management of elevated hemidiaphragm is determined by the severity of the disease and the underlying etiology. The severity of the disease is assessed by the level of respiratory impairment based on patient presentation, imaging, and lab results. Those with elevated hemidiaphragm should also be evaluated for chronic comorbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart failure, or obesity that can augment the severity of respiratory symptoms. The most definitive treatment for elevated hemidiaphragm is to treat the underlying pathology.

A patient presenting with respiratory distress or complete diaphragm paralysis may require endotracheal intubation and ventilation. However, most patients with elevated hemidiaphragm are asymptomatic. Asymptomatic patients with idiopathic etiology may not require any intervention. Elevated hemidiaphragm caused by phrenic nerve impairment can be transient and may resolve without further intervention. In some patients, training targeted to strengthen inspiratory muscles, including the diaphragm, has shown benefit. Based on the severity of phrenic nerve impairment and diaphragm weakness, or the presence of respiratory symptoms, ventilator support at bedtime can be helpful.

Patients with elevated hemidiaphragm should be monitored with imaging studies periodically. No definitive test or timeline has been established for this screening. However, to minimize radiation exposure, an ultrasound every 3-6 months may be the ideal choice of monitoring the condition. Ultrasound is quickly becoming the gold standard as it shows the movement and size of the diaphragm in real-time for an adequate comparison over time.

In situations where diaphragmatic palsy has progressed to complete paralysis, the diaphragm has not healed within one year, or the work of breathing has increased, a more invasive approach with surgical diaphragmatic plication may be warranted. In several studies, diaphragm plication showed evidence of decreased dyspnea and improved lung function by 10 to 30%.[18] The preferred method is laparoscopic diaphragmatic plication, where the weakened hemidiaphragm is sewn to the central tendon and peripheral muscles.[19] With the weaker hemidiaphragm fixed taut, the lung can inflate, allowing for better ventilation and perfusion, and the work of the contralateral hemidiaphragm decreases.[18] Surgical intervention is contraindicated for patients with bilateral diaphragmatic weakness, neuromuscular disease, and obesity.(B2)

Intervention with phrenic nerve pacing may provide significant improvement of symptoms in patients with diaphragm palsy due to spinal cord injury and neuromuscular disease.[20] This laparoscopic procedure involves mapping the motor units of the diaphragm for the placement of electrodes at those sites. Electrical impulses are sent through an intact phrenic nerve, which stimulates the motor units of the diaphragm, causing it to contract. Some patients have been successfully weaned off ventilators with a good prognosis after undergoing phrenic nerve pacing.

Differential Diagnosis

Injury to the phrenic nerve or hemidiaphragm is a direct cause of elevated hemidiaphragm. Indirect causes of elevated hemidiaphragm include a traumatic injury, neurologic disease, or cancerous processes within the thoracic and abdominal cavity. The presenting symptoms of diaphragm disease can range from asymptomatic to severe respiratory distress. Diagnosing the cause of elevated hemidiaphragm is vital to its treatment and management. However, several conditions may present with similar symptoms and radiographic findings, which should be ruled out.

The differential diagnosis for elevated hemidiaphragm includes:

Subpulmonic Effusion - Fluid collected at the base of the lung and the line of demarcation may look similar to an elevated hemidiaphragm.

Diaphragmatic Hernia - Most commonly seen in newborns, a diaphragmatic hernia occurs when there is an incomplete closure of the diaphragm muscles, causing a pathological opening in the diaphragm. Morgagni hernia is usually in the anterior portion of the diaphragm, and radiograph examinations may resemble an elevated hemidiaphragm.

Diaphragmatic Rupture - Rupture of the diaphragm may occur secondary to traumatic injury.

Diaphragm or Pleural Tumor - The tumor may extend along the surface of the diaphragm or push on the diaphragm and resemble an elevated hemidiaphragm.

Prognosis

The prognosis of elevated hemidiaphragm depends on the severity and cause of elevated hemidiaphragm. If etiology is related to subdiaphragmatic organ pathology, surgical removal or repair can resolve the elevated hemidiaphragm. A patient with traumatic injury to the phrenic nerve will often have a better prognosis than those with bilateral diaphragm weakness caused by neuromuscular diseases. The most common cause of mortality in patients with neuromuscular disorders such as ALS, MS, or myasthenia gravis is respiratory failure secondary to diaphragm paralysis.

Complications

Complications of elevated hemidiaphragm related to neuropathic or muscular causes can lead to respiratory distress, which can progress to respiratory failure or heart failure. The complications are related to the diaphragm's inability to function as a primary muscle for respiration and secondary to impairment of the pressure gradient required for adequate blood flow to the heart.

Consultations

A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and management of elevated hemidiaphragm is the best. Following specialities coordination is needed.

- Pulmonologist

- Neurologist

- Thoracic surgeon

- Radiologist

- Intensive care provider

Deterrence and Patient Education

All patients with elevated hemidiaphragm should be educated to understand signs and symptoms that warrant emergency intervention, worsening of the disease, and the importance of adherence to follow-up care and medications. Patients with an underlying neuromuscular disease will warrant additional care with specialists such as neurologists, rheumatologists, or pulmonologists.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Elevated hemidiaphragm can be an incidental, asymptomatic finding or can be the cause of respiratory failure. The diaphragm is vital for respiration, specifically the inspiratory phase. A dysfunctional diaphragm will cause various degrees of dyspnea, and in severe cases, it can cause respiratory failure, which may lead to death. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the function and causes of dysfunction of the diaphragm.

Phrenic nerve injury remains one of the most common causes of elevated hemidiaphragm. Phrenic nerve pacing through diaphragm motor unit mapping and electrode placement has successfully assisted in the recovery of patients with spinal cord injury (SCI). Patients with SCI were weaned off from ventilator-supported breathing through phrenic nerve pacing.[21] The prognosis is dependent upon the health of the diaphragm itself, meaning the ability for the diaphragm to contract. In general, the prognosis of elevated hemidiaphragm depends on the mechanism of injury and degree of treatment for the underlying disease causing an elevated hemidiaphragm.

Typically, the prognosis of elevated hemidiaphragm yields spontaneous resolution with respiratory compensation. The prognosis is much worse when the diaphragm is entirely diseased, as seen in autoimmune, neuromuscular diseases. However, the same phrenic nerve pacing has proven to delay the demand for ventilator support in patients with ALS. They were directly reducing the risk of infection and ventilator-associated adverse events, which may positively impact the rate of survival.[20] Recent study results show that injury to the hemidiaphragm may also impair the contralateral healthy hemidiaphragm.[4] Care should be coordinated for the best patient outcome. Asymptomatic patients primarily require routine screening with their primary provider.

Patients who experience symptoms require a multi-disciplinary team, including primary care provider, neurologist, a cardiothoracic surgeon for possible diaphragmatic fixation or phrenic nerve stimulator, or pulmonologist. Additionally, they may require physical therapy or respiratory therapy to improve diaphragmatic strength.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Roussos C, Macklem PT. The respiratory muscles. The New England journal of medicine. 1982 Sep 23:307(13):786-97 [PubMed PMID: 7050712]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFell SC. Surgical anatomy of the diaphragm and the phrenic nerve. Chest surgery clinics of North America. 1998 May:8(2):281-94 [PubMed PMID: 9619305]

Kokatnur L, Rudrappa M. Diaphragmatic Palsy. Diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Feb 13:6(1):. doi: 10.3390/diseases6010016. Epub 2018 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 29438332]

Caleffi-Pereira M, Pletsch-Assunção R, Cardenas LZ, Santana PV, Ferreira JG, Iamonti VC, Caruso P, Fernandez A, de Carvalho CRR, Albuquerque ALP. Unilateral diaphragm paralysis: a dysfunction restricted not just to one hemidiaphragm. BMC pulmonary medicine. 2018 Aug 2:18(1):126. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0698-1. Epub 2018 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 30068327]

Thomas SC, Garg A, Pulkkinen C, Smith S, Kumar A, Atoui R. An Unusual Case of Cardiac Tamponade Secondary to an Elevated Right Hemidiaphragm. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2018 Dec:34(12):1688.e21-1688.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2018.10.008. Epub 2018 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 30527167]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKharma N. Dysfunction of the diaphragm: imaging as a diagnostic tool. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2013 Jul:19(4):394-8. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283621b49. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23715292]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcCaul JA, Hislop WS. Transient hemi-diaphragmatic paralysis following neck surgery: report of a case and review of the literature. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. 2001 Jun:46(3):186-8 [PubMed PMID: 11478021]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChapman SA, Holmes MD, Taylor DJ. Unilateral diaphragmatic paralysis following bronchial artery embolization for hemoptysis. Chest. 2000 Jul:118(1):269-70 [PubMed PMID: 10893396]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDoyle MP, McCarty JP, Lazzara AA. Case Study of Phrenic Nerve Paralysis: "I Can't Breathe!". The Journal of emergency medicine. 2020 Jun:58(6):e237-e241. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.03.023. Epub 2020 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 32354588]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCanbaz S, Turgut N, Halici U, Balci K, Ege T, Duran E. Electrophysiological evaluation of phrenic nerve injury during cardiac surgery--a prospective, controlled, clinical study. BMC surgery. 2004 Jan 14:4():2 [PubMed PMID: 14723798]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNguyen MTH, Reid FSW, Barnett SA, Bentley L, Rees MA. Unusual cause of an elevated hemidiaphragm: large right-sided spontaneous diaphragmatic hernia induced by severe chronic cough in an adolescent patient with asthma. Internal medicine journal. 2019 Feb:49(2):273-274. doi: 10.1111/imj.14196. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30754083]

Dubé BP, Dres M. Diaphragm Dysfunction: Diagnostic Approaches and Management Strategies. Journal of clinical medicine. 2016 Dec 5:5(12): [PubMed PMID: 27929389]

Deng Y, Byth K, Paterson HS. Phrenic nerve injury associated with high free right internal mammary artery harvesting. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2003 Aug:76(2):459-63 [PubMed PMID: 12902085]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAguirre VJ, Sinha P, Zimmet A, Lee GA, Kwa L, Rosenfeldt F. Phrenic nerve injury during cardiac surgery: mechanisms, management and prevention. Heart, lung & circulation. 2013 Nov:22(11):895-902. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.06.010. Epub 2013 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 23948287]

van Doorn PA, Ruts L, Jacobs BC. Clinical features, pathogenesis, and treatment of Guillain-Barré syndrome. The Lancet. Neurology. 2008 Oct:7(10):939-50. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70215-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18848313]

Gibson GJ. Diaphragmatic paresis: pathophysiology, clinical features, and investigation. Thorax. 1989 Nov:44(11):960-70 [PubMed PMID: 2688182]

Blumhof S, Wheeler D, Thomas K, McCool FD, Mora J. Change in Diaphragmatic Thickness During the Respiratory Cycle Predicts Extubation Success at Various Levels of Pressure Support Ventilation. Lung. 2016 Aug:194(4):519-25. doi: 10.1007/s00408-016-9911-2. Epub 2016 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 27422706]

Groth SS, Andrade RS. Diaphragm plication for eventration or paralysis: a review of the literature. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2010 Jun:89(6):S2146-50. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.021. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20493999]

Groth SS, Rueth NM, Kast T, D'Cunha J, Kelly RF, Maddaus MA, Andrade RS. Laparoscopic diaphragmatic plication for diaphragmatic paralysis and eventration: an objective evaluation of short-term and midterm results. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2010 Jun:139(6):1452-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.10.020. Epub 2010 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 20080267]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOnders RP, Elmo M, Khansarinia S, Bowman B, Yee J, Road J, Bass B, Dunkin B, Ingvarsson PE, Oddsdóttir M. Complete worldwide operative experience in laparoscopic diaphragm pacing: results and differences in spinal cord injured patients and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients. Surgical endoscopy. 2009 Jul:23(7):1433-40. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0223-3. Epub 2008 Dec 6 [PubMed PMID: 19067067]

Posluszny JA Jr, Onders R, Kerwin AJ, Weinstein MS, Stein DM, Knight J, Lottenberg L, Cheatham ML, Khansarinia S, Dayal S, Byers PM, Diebel L. Multicenter review of diaphragm pacing in spinal cord injury: successful not only in weaning from ventilators but also in bridging to independent respiration. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2014 Feb:76(2):303-9; discussion 309-10. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000112. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24458038]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence