Introduction

Eosinophils are a kind of blood granulocytes that express cytoplasmic granules that contain basic proteins and bind with acidic dyes like “eosin.” They derive from bone marrow, and IL-5, IL-3, and GM-CSF stimulate their production.[1] They have a circulating half-life of 4.5 to 8 hours. They can reside in tissues, mostly in the respiratory tract and gastrointestinal tract, for 8 to 12 days. Eosinophils are less than 5% of circulating leukocytes. Eosinophilia is defined as an increase of circulating eosinophils >500 /mm^3.[1]

Based on the counts, eosinophilia can subdivide into different categories: mild (500 and 1500/mm^3), moderate (1500 to 5000/mm3), and severe (> 5000/mm^3). Hypereosinophilic syndrome is defined as an absolute eosinophil count greater than 1500/mm3 on two occasions at least one month apart or marked tissue eosinophilia.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Eosinophilia can be primary or secondary[3]:

- Chronic eosinophilic leukemia

- Myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms with rearrangements of PDGFRA, PDGFRAB, or FGFR1 genes

- Hereditary eosinophilia

- Idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome

Secondary causes [4]:

- Parasitic infestations: ancylostomiasis, ascariasis, cysticercosis, echinococcosis (hydatid cyst), schistosomiasis, strongyloidiasis, trichinellosis, visceral larva migrans (toxocariasis)

- Fungal and bacterial infections: bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, chronic tuberculosis (occasionally), coccidioidomycosis, disseminated histoplasmosis, scarlet fever

- Allergic disorders: bronchial asthma, hay fever, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, drug, and food allergic reactions, DRESS syndrome

- Skin diseases: Atopic dermatitis, eczema, pemphigus, Mycosis fungoides, Sezary syndrome

- Graft versus host reaction

- Connective tissue disease: Chrug-Strauss syndrome, eosinophilic myalgia syndrome

- Miscellaneous: reactive pulmonary eosinophilia, tropical eosinophilia, pancreatitis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of eosinophilia are not well described. There is no sex predilection for eosinophilia. However, there can be geographical influences depending on its cause. Parasitic infestations are more prevalent in tropical countries. Allergic disorders are commonplace in developed countries.[5] Idiopathic hypereosinophilia is diagnosed between 20 and 50 years of age, but extreme ages at both ends of the curve are also known to occur.

Pathophysiology

Eosinophils become differentiated in bone marrow, and once they leave the marrow, they stop maturing further. They reside in tissues, mostly outside the vasculature. In eosinophil related disorders, eosinophils are recruited into the involved tissues. T helper-2 cells mediated immune responses, and IL-5 production induce eosinophilopoiesis and eosinophil activation. The major cytokine responsible for eosinophil production and activation is IL-5 [9,10]. After activation, eosinophils degranulate and release the cationic proteins into the tissues through which eosinophils perform their functions. These released proteins can be proteolytic enzymes, which can cause damage to the host wall as well. Eosinophil also releases cytokines, like IL-10 and IL-14, which aid in maintaining homeostasis and immunoregulation.[6][7]

Histopathology

An eosinophil is around 12 to 17 µm in diameter and has a segmented nucleus. It has abundant cytoplasmic granules that contain proteolytic enzymes. Four major proteins comprise the granules: major basic protein (MBP1), eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP), eosinophil derived neurotoxin (EDN), and eosinophil peroxidase (EOP). They stain red-orange with Romanowsky stains.[4]

History and Physical

Due to the heterogeneous manifestations of the disease and severity varying from mild to end-organ damage, comprehensive history taking and diligent physical examination is extremely important, and sometimes enough, for diagnosis.[4] Skin, pulmonary, and gastrointestinal organ systems are commonly involved. Constitutional symptoms like low-grade fevers, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss can occur in multiple conditions, including myeloproliferative and lymphoid neoplasms, Churg Strauss syndrome, DRESS syndrome.

Skin rashes, pruritus can be seen in cutaneous T cell lymphoma, eczema. Dyspnea, cough, wheezing can be seen in multiple conditions, including bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, Loeffler's syndrome, hay fever, asthma, reactive pulmonary eosinophilia, Churg strass syndrome. Detailed travel history, work environment, drug history, close contacts with HIV, syphilis helps identify infections, parasitic infestations, and drug adverse reactions.[8][9] Physical examination should be complete, including a skin assessment, lung auscultation to look for rhonchi, wheezes, abdomen exam to look for splenomegaly.

Evaluation

Secondary causes of eosinophilia should be ruled out first. The evaluation for primary eosinophilia should begin with screening peripheral blood for FIP1L1- PDGFRA gene fusion. Diagnostic testing should start with peripheral smear. Cytogenetic testing and FISH analysis can be performed on peripheral blood as well.[4][8]

Concurrent cytophilias or cytopenias, if present, can help with diagnosis. In that case, a bone marrow biopsy, along with karyotype and genetic screen of chromosomes, may be required.[5][10]

B12 level and tryptase level, along with cytogenetic/immunophenotypic testing and marrow findings, help diagnose chronic mastocytosis, acute/chronic myeloid leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and MDS/MPN overlap. When skin rashes are present, skin biopsy helps to diagnose cutaneous disorders like pemphigoid, eczema, mycosis fungoides, and Sezary syndrome. Imaging of the chest helps diagnose aspergillosis, Loeffler syndrome, and Churg Strauss syndrome. Ultrasound abdomen helps to evaluate for splenomegaly. Stool testing helps to assess for parasitic infections.

Treatment / Management

Management depends on the underlying cause. The goal of the therapy is to mitigate end-organ damage from eosinophilia.[10] In mild cases without any symptoms or signs of organ involvement, a conservative approach can be undertaken. In emergency conditions with hemodynamic instability or organ failure, treatment with IV steroids is important.[8]

For some conditions like drug and food allergies or infections, treatment can be simple, like withdrawing the offending agent or treating it with antibiotics. But in some conditions, due to the varying clinical manifestations and multi-systemic involvement, an interprofessional approach involving hematologists, pulmonologists, and infectious disease specialists, might be necessary. In steroid-resistant cases of hypereosinophilic syndrome and chronic eosinophilic leukemia, hydroxyurea and interferon-alpha have demonstrated efficacy.

In aggressive forms of the disease, second-line cytotoxic agents and stem cell transplants have proven some benefits. Antibody use against interleukin-5 (IL-5) (mepolizumab), the IL-5 receptor (benralizumab), and CD52 (alemtuzumab), as well as other targets on eosinophils, continues to be an active area of investigation.[10][9] Timely intervention is vital to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnoses can be narrowed down based on the predominant system involved. For example, when manifested with pulmonary symptoms: asthma, bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, with hay fever: skin involvement: Mycosis fungoides, Sezary syndrome, eczema, and bullous pemphigoid.

Prognosis

Prognosis can be varying from mild disease to fatal outcome, depending on multiple factors like the cause of the eosinophilia, the presence of organ damage, the subtype of eosinophilia, and the timeline of intervention.

Complications

As eosinophils can produce proinflammatory cytokines and contain proteolytic enzymes that can damage the host cell wall, tissue damage can occur if not treated appropriately. Based on the etiology, the outcome can be fatal and cause severe end-organ damage.

Deterrence and Patient Education

When multiple symptoms are not explainable or when there is an exacerbation of an underlying condition without any risk factors, patients need to seek prompt medical attention. They need to give their physician a detailed history, including their living conditions, travel, and medications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

When there is no obvious cause found, pathologists should recommend further hematology testing like FISH analysis and cytogenetics. When there is a multi-systemic involvement, early intervention with an interprofessional approach helps.[8]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

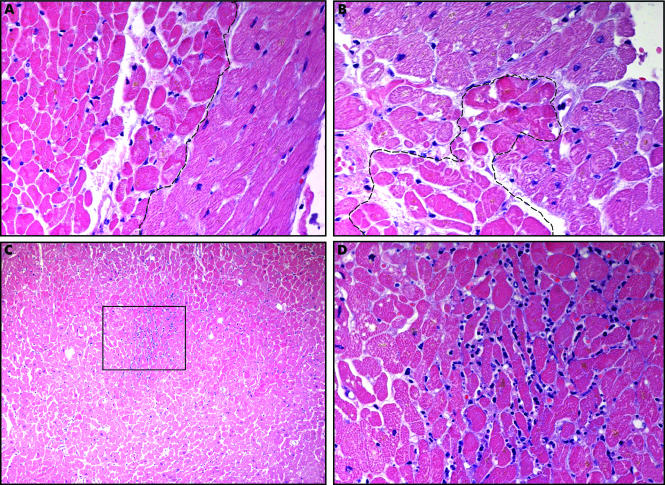

Coagulative Necrosis in Myocytes During Silent Myocardial Ischemia. Small foci of coagulative necrosis can be recognized on hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections: ischaemic myocytes typically show the hypereosinophilia that characterizes early phases of coagulative necrosis. (A) The ischemic myocytes are located on the left side of the panel; (B) the ischemic myocytes are positioned at the bottom left; (C) low magnification view showing a small area of acute myocardial infarction in which granulocyte infiltration is visible among the myocytes showing coagulative necrosis (squared area and (D), inset at higher magnification). The front of the myocardial ischemia is in the top half of the image.

Pasotti M, Prati F, Arbustini E. The pathology of myocardial infarction in the pre- and post-interventional era. Heart. 2006;92(11):1552-1556. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.086934.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kovalszki A, Weller PF. Eosinophilia. Primary care. 2016 Dec:43(4):607-617. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2016.07.010. Epub 2016 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 27866580]

Klion AD. Eosinophilia: a pragmatic approach to diagnosis and treatment. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2015:2015():92-7. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.92. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26637706]

Magnaval JF, Laurent G, Gaudré N, Fillaux J, Berry A. A diagnostic protocol designed for determining allergic causes in patients with blood eosinophilia. Military Medical Research. 2017:4():15. doi: 10.1186/s40779-017-0124-7. Epub 2017 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 28546866]

Larsen RL, Savage NM. How I investigate Eosinophilia. International journal of laboratory hematology. 2019 Apr:41(2):153-161. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12955. Epub 2018 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 30499630]

Naymagon L, Marcellino B, Mascarenhas J. Eosinophilia in acute myeloid leukemia: Overlooked and underexamined. Blood reviews. 2019 Jul:36():23-31. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2019.03.007. Epub 2019 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 30948162]

Fulkerson PC, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophil Development, Disease Involvement, and Therapeutic Suppression. Advances in immunology. 2018:138():1-34. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2018.03.001. Epub 2018 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 29731004]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiao W, Long H, Chang CC, Lu Q. The Eosinophil in Health and Disease: from Bench to Bedside and Back. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2016 Apr:50(2):125-39. doi: 10.1007/s12016-015-8507-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26410377]

Butt NM,Lambert J,Ali S,Beer PA,Cross NC,Duncombe A,Ewing J,Harrison CN,Knapper S,McLornan D,Mead AJ,Radia D,Bain BJ, Guideline for the investigation and management of eosinophilia. British journal of haematology. 2017 Feb [PubMed PMID: 28112388]

Leiferman KM, Peters MS. Eosinophil-Related Disease and the Skin. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology. In practice. 2018 Sep-Oct:6(5):1462-1482.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.06.002. Epub 2018 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 29902530]

Gotlib J. World Health Organization-defined eosinophilic disorders: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and management. American journal of hematology. 2017 Nov:92(11):1243-1259. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24880. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29044676]