Introduction

Epiglottitis is an inflammatory condition, usually infectious in origin, of the epiglottis and nearby structures like the arytenoids, aryepiglottic folds, and vallecula. Epiglottitis is a life-threatening condition that causes profound swelling of the upper airways which can lead to asphyxia and respiratory arrest.[1] Before the development of the Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine, the majority of cases were caused by H.influenzae and the condition was far more common. In the post-vaccine era, the pathogens responsible are more varied and can also be polymicrobial. For this reason, the term "supraglottitis" is often preferred, as the infections may affect the supraglottic structures more generally. Edema due to infection of the epiglottis and supraglottic structures can be gradually progressive until a critical mass is reached, and the clinical scenario can rapidly deteriorate and lead to airway obstruction, respiratory distress, and death. Symptoms can be exacerbated by patient discomfort and agitation, particularly in children, so any patient with a diagnosis of true supraglottis must have their airway secured under the most controlled circumstances possible, and every attempt should be made to keep the patient as calm and comfortable as possible until an airway is secured. The airway should not be instrumented for oral exams or endoscopy in the clinic or Emergency Department, and no patient with a potentially unstable airway should be sent to the radiology department for imaging.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The cause of epiglottitis is most commonly infectious, whether bacterial, viral, or fungal in origin. In children, Haemophilus influenzae type B (HIB) is still the most common cause. However, this has decreased dramatically since the widespread availability of immunizations. Other agents such as Streptococcus pyogenes, S pneumoniae, and S aureus have been implicated. In patients who are immunocompromised, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida have been named. Noninfectious causes can be traumatic such as thermal, caustic, or foreign body ingestion.[2][3][4]

While viruses do not cause epiglottitis, a prior viral infection may allow bacterial superinfection to develop. Viruses that may allow a superinfection include varicella-zoster, herpes simplex, and Epstein-Barr virus.

Epidemiology

Since the addition of the HIB vaccine to the infant immunization schedule in many countries worldwide, the annual incidence of epiglottitis in children has decreased overall. However, the incidence in adults has remained stable. Additionally, the age of children who have had epiglottitis has increased from three years old to six to twelve years old in the post-vaccine era.[5] While in the past epiglottitis was thought to be primarily a disease of young children, it is now much more likely practitioners will encounter epiglottitis/supraglottitis in adults as well.

Pathophysiology

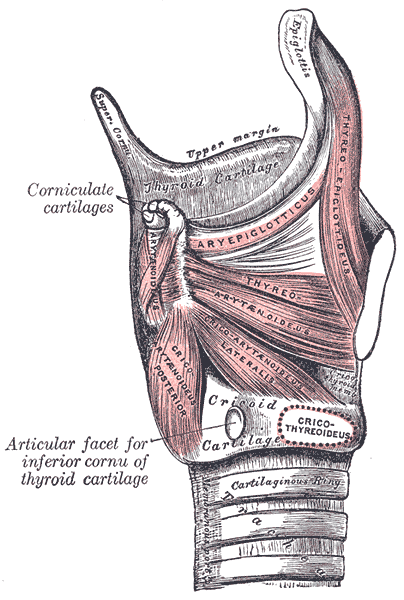

The airway in the pediatric population is markedly different compared to that of an adult (see Image. The Muscles of the Larynx). In a young child, the epiglottis is located more superiorly and anteriorly than in an adult. There is also a more oblique angle with the trachea. The narrowest portion of the infant and pediatric airway is the subglottis, while in adults it is the glottis. Furthermore, the infant epiglottis is comprised of cartilage that is far more pliant when compared to that of an adult, whose epiglottis is more rigid (this is the natural progression of cartilage maturation, and explains why laryngomalacia is more prevalent in very young children). It is not surprising, then, that an infectious process that leads to edema and increase in weight and mass of the epiglottis is more likely to cause symptoms in a child - the pliancy of the cartilage allows a ball-valve effect, where each inspiration pulls an edematous epiglottis over the laryngeal airway, causing symptoms. In adults, whose cartilages are stiffer, an isolated epiglottic infection and the resultant increase in epiglottic mass may be resisted by the more rigid laryngeal/epiglottic cartilage; but an infection that encompasses more of the tissues of the supraglottis, leading to edema, can lead to symptoms and an unstable airway.

H. influenzae and other, infections of the epiglottis can lead to marked edema and swelling 0f the epiglottis and supraglottis of patients of any age. This edema can rapidly spread to adjacent structures leading to the rapid development of airway obstruction symptoms. While H. influenzae remains the most common pathogen in both adults and children, other organisms such as S. Pneumoniae, S. aureus, and beta-hemolytic Streptococcus sp. are important pathogens also in both adults and children. In immunocompromised patients, the list of potential causes is much longer and must include Mycobacterium tuberculosis, as well as a litany of others, though the relative frequencies remain the same.

Toxicokinetics

Other complications of epiglottitis include:

- Cervical adenitis

- Empyema

- Epiglottic abscess

- Meningitis

- Pneumonia

- Pneumothorax

- Sepsis

- Septic arthritis

- Septic shock

- Vocal cord granuloma

- Ludwig angina-type submental infection

History and Physical

The history will often reveal an antecedent URI, though not always. Symptoms may be very mild for a period of hours to days, until they dramatically worsen, mimicking a sudden onset. This will usually have occurred within the past 24 hours, or sometimes the last 12 hours. The patient will appear very uncomfortable, and possibly overtly toxic. Most children have no prodromal symptoms. In the emergency department, the child will likely be sitting upright with the mouth open in a tripod position and possibly have a muffled voice. Adults may be minimizing symptoms, but will likely be reluctant to lie flat or be uncomfortable when doing so. Drooling, dysphagia, and distress, or anxiety may be present (especially in children, but also in adults). These are often referred to as the 3 Ds. Swelling of the upper airway results in turbulent airflow during inspiration or stridor. Signs of severe upper airway obstruction such as intercostal or suprasternal retractions, tachypnea, and cyanosis are concerning for impending respiratory failure and should signal the provider to act quickly. Avoid an exam of the throat with a tongue blade or a flexible laryngoscope, as it may result in the loss of the airway.

Anterior examination of the neck may reveal lymphadenopathy. If cyanosis is present, it is indicative of advanced infection and poor prognosis.

Evaluation

An oropharyngeal exam is usually not performed to evaluate a suspected case of epiglottitis because manipulation of the oral cavity may lead to disaster, such as respiratory arrest. This diagnosis is primarily one of clinical suspicion. A lateral neck radiograph will show swelling of the epiglottis, also referred to as the “thumb sign.” See Image. Lateral X-ray, Epiglottitis. It is not necessary to make the diagnosis but can be used to narrow down the provider’s differential diagnosis. This should only be performed in the most stable, comfortable, and cooperative of patients. A flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy can be performed theoretically, but only in a very controlled setting such as the operating room due to the risk of inducing laryngospasm. This is almost always never done. If clinical suspicion for acute epiglottitis exists, the patient should be taken emergently to the operating room for airway examination under the most optimal conditions possible.

Ultrasonography has been mentioned as another way to evaluate these patients, revealing an “alphabet P sign” in a longitudinal view. This must also be weighed against the clinical condition and may be ill-advised in children. A complete blood count with differential, a blood culture, and an epiglottal culture should only be obtained in patients with a secured endotracheal tube.[6]

CT scan of the neck is rarely needed and can precipitate disaster. Placing the patient in a supine position can trigger respiratory crises. If this diagnosis is yielded unexpectedly on a CT scan, the child (or adult) should not be left alone in the radiology suite and should be transported emergently to the operating room for airway evaluation and intubation.

The chest x-ray may reveal concomitant pneumonia in 10-15% of patients. A lateral neck X-ray can be obtained in select cooperative patients as detailed previously (with great caution). A standard portable P-A X-ray may also suggest the diagnosis via a narrowing of the laryngotracheal area easily confused with the "steeple sign" of laryngotracheal bronchitis (croup). Therefore, this remains a purely clinical diagnosis.[7]

Treatment / Management

The singular, most important, aspect of treatment is to secure the airway. Experienced providers should intubate these patients since their airways are regarded as difficult. An individual capable of performing a tracheotomy should be available if needed. This likely involves an inhalation induction of general anesthesia and subsequent intubation, though this varies from patient to patient. The patient should be admitted to the intensive care unit after the airway is secured, and culture swabs should be sent at the time of intubation after the tube is placed. The use of corticosteroids to reduce edema has been cited, with an overall shorter intensive care unit stay for these patients. Empiric antimicrobials should be initiated. Once culture and sensitivity results are available, the regimen should be adjusted. Once a leak around the endotracheal tube can be demonstrated with the cuff deflated, extubation can be entertained.[8][9](B2)

All non-intubated patients must be admitted for observation and a tracheostomy tray must be available at the bedside. The ENT surgeon and the anesthesiologist must be notified of the admission in case an emergency airway is required. Nurses should be warned not to place the child in a supine position. In reality, this is rare - patients with a high suspicion of epiglottitis should be intubated as soon as possible.

If an emergency airway is needed, it should ideally be obtained in the operating room. The airway should be visualized with a laryngoscope first. if endotracheal intubation is not an option, then a tracheostomy should be performed.

Antibiotics usually administered should cover common respiratory and oral cavity flora, and can include cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, and cefotaxime.

Differential Diagnosis

Because of the availability of the HIB vaccine, acute epiglottitis due to H. influenzae is less common (though this is sporadically increasing due to public misconception regarding vaccination), though still remains the single most common pathogen responsible for the condition in both adults and children. Thus, most health care providers may have less insight into the disorder. This lack often leads to delays in starting antibiotics. Acute epiglottitis can result in sudden airway obstruction. It is never wise to send the patient anywhere without proper monitoring and resuscitative equipment if this diagnosis is remotely suspected.

Other conditions that can mimic the presentation include an airway obstruction from a foreign object, acute angioedema, caustic ingestion causing airway compromise, diphtheria, or peritonsillar and retropharyngeal abscesses.

Prognosis

For most patients with epiglottitis, the prognosis is good when the diagnosis and treatment are prompt. Even those who require intubation are usually extubated in a few days without any residual sequelae. However, when the diagnosis is delayed in children, airway compromise can occur, and death is possible.

The cause of death is usually due to sudden upper airway obstruction and difficulty intubating the patient, with extensive swelling of the laryngeal structures. Thus, every patient admitted with a diagnosis of acute epiglottitis must be seen by an ear, nose, and throat surgeon or anesthesiologist, and a tracheostomy tray must be made available at the bedside. Globally, a mortality rate of 3% to 7% has been reported in patients with unstable airways.

Complications

Complications of epiglottitis include the following:

- Cellulitis

- Cervical adenitis

- Death

- Empyema

- Epiglottic abscess

- Meningitis

- Pneumonia

- Pulmonary edema

- Respiratory failure

- Septic shock

- Hypoxia

- Prolonged ventilation

- Tracheostomy

- Death

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Once the patient is admitted, the following care is necessary:

- Do not agitate the patient

- Administer humidified oxygen

- Allow the patient to choose the position which is most comfortable

- Avoid the use of inhalers and sedatives

- Be prepared for a sudden worsening of the clinical condition

- Always have a tracheostomy cut down set at the bedside

With appropriate treatment, most patients improve within 48-72 hours but antibiotics are still required for 7 days. Only afebrile patients should be discharged home.

Consultations

Once a patient has been diagnosed with acute epiglottitis, the following professionals should be consulted:

- Anesthesiologist, in case an airway is required

- Ear, nose, and throat specialist or surgeon, in case a tracheostomy is needed

- Intensivist

- Infectious disease specialist

- Pulmonologist

Deterrence and Patient Education

Close contacts of patients with H. influenzae who are not immunized should be prescribed rifampin prophylaxis. One may opt to administer the HIB vaccine, but it is not 100% effective.

Patients who have recurrent episodes of acute epiglottitis warrant investigation for immunosuppression.

To prevent epiglottitis, vaccination should be encouraged. Children should be immunized according to the schedule prescribed by the WHO.

Pearls and Other Issues

Clinical Negligence Leading to Malpractice

- Underestimating the potential for sudden airway compromise and respiratory arrest

- Failure to send the patient to a monitored room or inadequate monitoring

- Failure to have a tracheostomy set at the bedside

- Rushing to intubate the patient without having a support team that includes an ear, nose, and throat surgeon or anesthesiologist

- Performing an oral exam that results in irritation of the upper airways and sudden airway compromise, leading to death

- Sending an unstable airway to radiology

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Epiglottitis is a relatively common fear in the emergency department, but actually rather rare. Because of its high morbidity and mortality, ER providers must be familiar with its presentation and management and it is highly recommended that the disorder be managed by an interprofessional team that includes an intensivist, pulmonologist, infectious disease consult, anesthesiologist, and an ENT surgeon. Since most patients present to the emergency room, it is important that the triage nurse and emergency room physician know the signs and symptoms of the disorder. The condition can rapidly lead to respiratory distress and death.

Once the patient has been admitted, the emergency department physician should consult with an infectious disease expert and the ENT surgeon. Nurses should be educated about not placing the patient supine and the importance of monitoring oxygenation. Nurses should also be aware that the patient should never be allowed to go to a radiology suite alone and without monitoring equipment.

Some patients may require mechanical ventilation for a few days. However, all patients with acute symptoms must be admitted, and a tracheostomy tray must be available at the bedside. The oral cavity should not be probed until the airway is secure, and the patient must not be stressed. Once the patient is admitted, the ENT surgeon must be notified in case there is a need for an airway if they have not been intubated already.[10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Muscles of the Larynx. The larynx muscles (side view) are the aryepiglotticus, epiglottis, thyroarytenoid, cricoarytenoid posterior, and lateral.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Baird SM, Marsh PA, Padiglione A, Trubiano J, Lyons B, Hays A, Campbell MC, Phillips D. Review of epiglottitis in the post Haemophilus influenzae type-b vaccine era. ANZ journal of surgery. 2018 Nov:88(11):1135-1140. doi: 10.1111/ans.14787. Epub 2018 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 30207030]

Schröder AS, Edler C, Sperhake JP. Sudden death from acute epiglottitis in a toddler. Forensic science, medicine, and pathology. 2018 Dec:14(4):555-557. doi: 10.1007/s12024-018-9992-8. Epub 2018 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 29926438]

Tsai YT, Huang EI, Chang GH, Tsai MS, Hsu CM, Yang YH, Lin MH, Liu CY, Li HY. Risk of acute epiglottitis in patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: A population-based case-control study. PloS one. 2018:13(6):e0199036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199036. Epub 2018 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 29889887]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChen C, Natarajan M, Bianchi D, Aue G, Powers JH. Acute Epiglottitis in the Immunocompromised Host: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Open forum infectious diseases. 2018 Mar:5(3):ofy038. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy038. Epub 2018 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 29564363]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceButler DF, Myers AL. Changing Epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae in Children. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2018 Mar:32(1):119-128. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.10.005. Epub 2017 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 29233576]

Shapira Galitz Y, Shoffel-Havakuk H, Cohen O, Halperin D, Lahav Y. Adult acute supraglottitis: Analysis of 358 patients for predictors of airway intervention. The Laryngoscope. 2017 Sep:127(9):2106-2112. doi: 10.1002/lary.26609. Epub 2017 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 28493349]

Solomon P, Weisbrod M, Irish JC, Gullane PJ. Adult epiglottitis: the Toronto Hospital experience. The Journal of otolaryngology. 1998 Dec:27(6):332-6 [PubMed PMID: 9857318]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGottlieb M, Long B, Koyfman A. Clinical Mimics: An Emergency Medicine-Focused Review of Streptococcal Pharyngitis Mimics. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2018 May:54(5):619-629. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.01.031. Epub 2018 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 29523424]

Lindquist B, Zachariah S, Kulkarni A. Adult Epiglottitis: A Case Series. The Permanente journal. 2017:21():16-089. doi: 10.7812/TPP/16-089. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28241903]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDamm M, Eckel HE, Jungehülsing M, Roth B. Airway endoscopy in the interdisciplinary management of acute epiglottitis. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 1996 Dec 5:38(1):41-51 [PubMed PMID: 9119592]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence