Introduction

Erythema toxicum neonatorum is a condition that has been described (rash) as early as the 15th century by a pediatrician named B. Metlinger. It has been associated with a reaction to meconium to the skin of the baby, and the name of the condition has changed several times over the years, from erythema populated to erythema dyspepsia and erythema neonatorum allergicum. In 1912, Dr. Karl Leiner, an Austrian pediatrician, named the condition erythema toxicum neonatorum and currently this is the denomination used for these skin findings.[1]

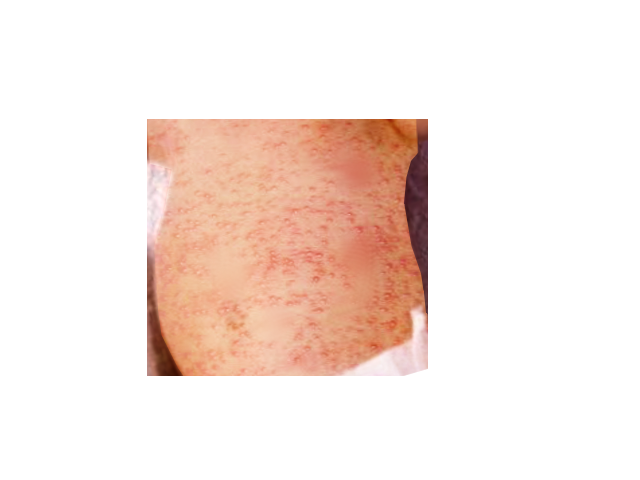

The eruption features small yellowish pustules and papules that are surrounded by an irregular reddish wheal. The majority of lesions are temporary, often disappearing within a few hours and reappearing elsewhere. Asides from the soles and palms, these lesions can occur on any part of the body.

The skin disorder presents within the first week of life and usually resolves within 7-14 days.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Erythema toxicum neonatorum is a benign, self-limited, transient, evanescent eruption that occurs in approximately 48% to 72% of full-term infants. A 1986 study reported that 40.8% of 5387 Japanese neonates examined over a period of 10 years were identified as having erythema toxicum neonatorum. Preterm infants with birth weight less than 2500 grams are less likely to be affected.[2][3]

There are a significant amount of eosinophils in the lesions, which some suspect may be due to an allergic response.

Epidemiology

While there is no racial predilection, males appear more commonly affected compared to females. In 356 Spanish newborns, 25.3% had erythema toxicum neonatorum (61.9% were males, and 38.1% were females). Recurrence is exceedingly rare, although there have been some reports of recrudescence within the first month of life. [4]

Pathophysiology

The etiology of this condition is completely unknown: a graft-versus-host reaction against maternal lymphocytes has been postulated as a possible mechanism, but recent studies failed to show the presence of maternal cells in these lesions. Another theory proposes an immune response to microbial colonization through the hair follicles as early as one day of age. Immunohistochemical study of lesions from 1-day-old infants supports the accumulation and activation of immune cells in erythema toxicum neonatorum lesions. A variety of inflammatory mediators such as IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-8, eotaxin, aquaporins 1 and 3, psoriasin, nitric oxide synthetases 1, 2 and 3, and HMGB-1 have been associated with erythema toxicum neonatorum immunohistochemically. Tryptase-expressing mast cells, however not the cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide LL-37, have been located in erythema toxicum neonatorum biopsy specimens.

Histopathology

The pustules form below the stratum corneum or deeper in the epidermis and represent collections of eosinophils that also accumulate around the upper portion of the pilosebaceous follicle. The eosinophils can be demonstrated in Wright-stained smears of the intralesional contents. The pustules usually contain around 50% eosinophils, and it can approach up to a 95%. Cultures are sterile, no organisms are seen on Gram stain. Microscopic observation of the erythematous macules and patches shows superficial dermal edema with a mild diffuse and perivascular eosinophilic infiltrate. Papules display mild hyperkeratosis and a more pronounce edema with eosinophilic infiltration. Hair follicles, eccrine glands, and ducts tend to be strongly affected.

History and Physical

The lesions are firm, yellow-white, 1 to 3-mm papules or pustules with a surrounding irregular erythematous base. They also have been described as having a “flea-bitten appearance” or a papule surrounded by a sea of erythema. At times, splotchy erythema is the only manifestation. Lesions may be sparse or numerous and they can be either clustered in several sites or widely dispersed over much of the body surface.

Erythema toxicum neonatorum has been described as consisting of two likely variations: an erythematous papular or a pustular variant. During the first day of presentation, macules tend to appear within and outside the erythematous lesions. It usually begins on the cheeks and rapidly spreads to the forehead, the rest of the face, chest, trunk, and extremities but there are several case reports of patients with erythema toxicum neonatorum lesions over the skin of the scrotum. The blotchy appearance ensues as the macules become confluent, sometimes resembling urticarial lesions on the trunk. The palms and soles are usually spared, this pattern of involvement may be correlated to the distribution of hair follicles.

Clinicians have a harder time seeing erythema toxicum neonatorum in babies with darker skin. This makes the identification of the problem somewhat challenging. Erythematous macules often are evanescent, but when they persist, papules then tend to appear, papules also may arise as de novo. Some papules may become superficial, particularly on the skin of the back and abdomen. It is very uncommon for the pustules to become secondarily infected. The peak incidence occurs on the second day of life, but new lesions may erupt during the first few days as the rash waxes and wanes, although recurrences may occur in up to 11% of neonates. The onset may occasionally be delayed for a few days to weeks in premature infants. There is no systemic manifestation associated with the condition, and one might rarely see some eosinophilia in blood studies and counts as high as 18% have been reported.[5][6]

Evaluation

No laboratory workup is usually required as the diagnosis in most cases is clinical. The sterile papule may reveal eosinophils. In some infants, herpes simplex and varicella-zoster should be ruled out. Fungal infection should be ruled out with a simple potassium hydroxide preparation

Treatment / Management

Treatment starts with education to the parents about the natural course of the condition: it is benign and will resolve without any sequelae. Because of the appearance of the rash creates great parental concerns, reassuring the parents has paramount significance.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis to this condition includes sepsis, staphylococcal folliculitis, acne neonatorum, pyoderma, congenital candidiasis, herpes simplex, infantile acropustulosis, neonatal varicella, pustular miliaria, miliaria cristalina, miliaria rubra, transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) and incontinentia pigmenti.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis and incontinentia pigmenti can be distinguished without any difficulty from erythema toxicum neonatorum. Transient neonatal pustular melanosis present at birth as does erythema toxicum neonatorum, but transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) involves the palms and soles, there is no erythematous component, and it shows only neutrophils with cytologic debris. However, both condition can present at the same time. Incontinentia pigment presents with vesicles filled with eosinophils, and it is more common in boys but is rarely pustular, and the appearance is in a linear pattern different from the pattern of erythema toxicum neonatorum. The distribution of the rash can also be useful to differentiate erythema toxicum neonatorum from infantile acropustulosis, while erythema toxicum neonatorum spares the palm and soles, the hallmark of infantile acropustulosis characteristically include the acral surfaces hence its name. Erythema toxicum neonatorum can be differentiated from miliaria rubra, a condition in which the vesicles are related to the sweat ducts rather than hair follicles and the lesions containing mononuclear cells rather than eosinophils. Congenital cutaneous candidiasis can also present at birth or in the first days of life, with a diffuse erythematous rash with overlying papules, pustules and vesicles, but the palms and soles are not spared.

Prognosis

The prognosis is excellent with lesions resolving within 7-14 days. There are no residual sequelae.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Long term follow-up is required as there is a link between erythema toxicum and eosinophilic esophagitis. Children who do present with symptoms of esophagitis should be asked about a rash in the neonatal period.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Erythema toxicum is a benign self-limited skin disorder that is only seen in neonates. Unfortunately, many worried parents bring the child to the healthcare provider for treatment and undergo unnecessary testing and treatment. When the primary care clinician is unsure about the diagnosis, a dermatology referral is recommended.

The key to this disorder is parent education. The primary care provider, nurse practitioner, pharmacist and healthcare professionals in the emergency department need to reassure the parent that the disorder is harmless and will resolve spontaneously. Parents should be told to avoid unnecessary treatments as this may lead to more harm than good.

The prognosis for most neonates is excellent, with the rash resolving in 10-14 days.[7]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Reginatto FP, Muller FM, Peruzzo J, Cestari TF. Epidemiology and Predisposing Factors for Erythema Toxicum Neonatorum and Transient Neonatal Pustular: A Multicenter Study. Pediatric dermatology. 2017 Jul:34(4):422-426. doi: 10.1111/pde.13179. Epub 2017 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 28543629]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceReddy HB, Gandra NR, Katta TP. Cutaneous Changes in Neonates in the First 72 Hours of Birth: An Observational Study. Current pediatric reviews. 2017:13(2):136-143. doi: 10.2174/1573396313666170216120230. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28215177]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRayala BZ, Morrell DS. Common Skin Conditions in Children: Neonatal Skin Lesions. FP essentials. 2017 Feb:453():11-17 [PubMed PMID: 28196316]

Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian journal of dermatology. 2015 Mar-Apr:60(2):211. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.152558. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25814724]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReginatto FP, DeVilla D, Muller FM, Peruzzo J, Peres LP, Steglich RB, Cestari TF. Prevalence and characterization of neonatal skin disorders in the first 72h of life. Jornal de pediatria. 2017 May-Jun:93(3):238-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2016.06.010. Epub 2016 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 27875703]

Reginatto FP, Villa DD, Cestari TF. Benign skin disease with pustules in the newborn. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2016 Apr:91(2):124-34. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164285. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27192509]

Kanada KN, Merin MR, Munden A, Friedlander SF. A prospective study of cutaneous findings in newborns in the United States: correlation with race, ethnicity, and gestational status using updated classification and nomenclature. The Journal of pediatrics. 2012 Aug:161(2):240-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.02.052. Epub 2012 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 22497908]