Introduction

The most prevalent cause of infectious esophagitis is esophageal candidiasis. Of patients that have infectious esophagitis, 88% are from Candida albicans, 10% are from herpes simplex virus, and 2% are from cytomegalovirus. Patients with esophageal candidiasis may have a wide range of symptoms or may be asymptomatic. The most common symptoms being dysphagia, odynophagia, and retrosternal pain. Candida infections of the esophagus are considered opportunistic infections and are seen most commonly in immunosuppressed patients. Candida can be part of the normal oral flora. When host defense mechanisms are impaired, this allows for a proliferation of candida on the esophageal mucosa forming adherent plaques. Esophageal candidiasis can is treatable with various forms of oral and intravenous antifungal medications.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

By far the highest risk factor for developing esophageal candidiasis is impaired cell-mediated immunity. Immunosuppressed patients at risk for esophageal candidiasis include HIV positive and AIDS patients, chemotherapy patients, patients with radiation to the neck region, antibiotic therapy, patients on chronic systemic or topical inhaled corticosteroids, diabetes mellitus, adrenal insufficiency, and advanced age.[1][2] Studies have shown that the use of proton-pump inhibitors is also a strong risk factor for esophageal candidiasis in immunocompetent patients.

Epidemiology

Studies have not shown a predominance of esophageal candida in either sex. Increasing age, HIV infection and the use of corticosteroids have been found to correlate with candidal esophagitis. The median age of a person with esophageal candidiasis is 55.5 years. Several studies have shown esophageal candidiasis incidence rates ranging from 0.32 to 5.2% in the general population. There is a 9.8% prevalence in HIV-positive patients. The risk of esophageal candidiasis increases in HIV patients when the CD4 count is less than 200. The prevalence of esophageal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients appears to be decreasing due to the effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HARRT). However, the incidence in non-HIV patients appears to be increasing, possibly due to comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus or from medications such as antibiotics and corticosteroids. Some studies show that smoking tobacco also correlates with developing esophageal candidiasis.[2][3][4]

Pathophysiology

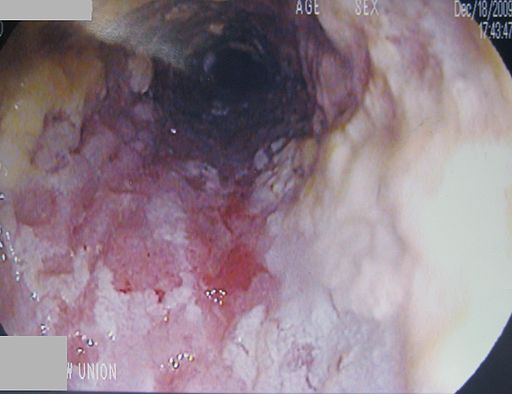

Candida albicans can be part of the normal oral flora. Due to impaired cell-mediated immunity, the esophageal epithelial layer is susceptible to infection and colonization by candida. The candida proliferates and adheres to the esophageal mucosa forming white-yellow plaques. The plaques can be seen on upper endoscopy and do not wash from the mucosa with water irrigation. These plaques can be found diffusely throughout the entire esophagus or localized in the upper, mid, or distal esophagus.[2]

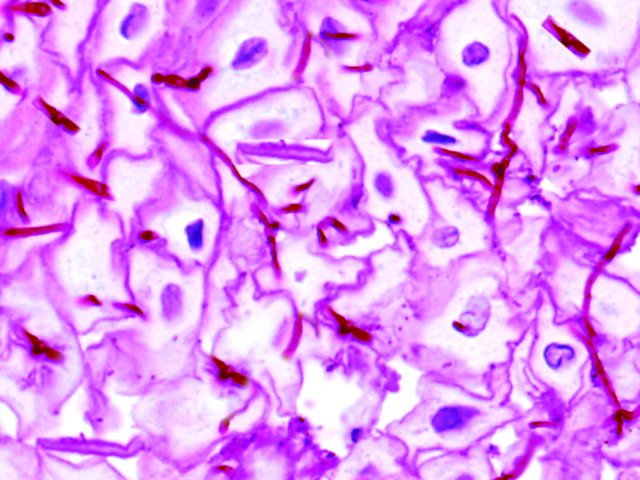

Histopathology

Histologic confirmation of candida in the esophagus is the gold standard for diagnosis. Hematoxylin and eosin stain of biopsies or brushing of esophageal candidiasis almost always show pseudohyphae which is diagnostic for esophageal candidiasis. The mucosa involved may exhibit desquamated parakeratosis which characteristically has groups of squamous cells that have detached or are in the process of detaching from the main squamous-lined tissue. This finding is not however specific to esophageal candidiasis. Pathology may demonstrate acute inflammation and/or intraepithelial lymphocytosis.[2]

History and Physical

Patients with esophageal candidiasis can have a multitude of complaints; however, patients are often asymptomatic. The most common symptoms associated with esophageal candidiasis are dysphagia, odynophagia, and retrosternal chest pain. Odynophagia is considered to be the hallmark of esophageal candidiasis. Other symptoms include abdominal pain, heartburn, weight loss, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, melena.[1][2]

The only finding may be an associated infection of the oropharynx with candida.

Evaluation

Diagnosing esophageal candidiasis is via upper endoscopic evaluation. Visualizing the candida on the esophageal mucosa as white plaques or exudates confirms the diagnosis. Plaques and exudates are adherent to the mucosa and do not wash off with water irrigation. There may also be mucosal breaks or ulcerations. Biopsies or brushings of the plaques can undergo testing for histologic confirmation of the infection.[1]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of esophageal candidiasis involves the use of antifungal therapy. Unlike oropharyngeal candidiasis, esophageal candidiasis should always be treated with systemic agents and not topical agents. The most commonly used medication to treat esophageal candidiasis is oral fluconazole 200 to 400 mg per day for 14 to 21 days. If patients cannot tolerate oral intake, then intravenous Fluconazole 400 mg daily can be used and then de-escalated to oral Fluconazole when the patient can tolerate oral medications. Fluconazole 100 to 200 mg three times per week can be used to suppress recurrent esophageal candidiasis. Micafungin 150 mg IV daily has been shown to be non-inferior to fluconazole at 200 mg daily. Itraconazole 200 mg per day orally or Voriconazole 200 mg twice daily for 14 to 21 days are other treatment options. Amphotericin B deoxycholate 0.3 to 0.7 mg/kg daily can be used in patients with refractory candida esophagitis, but it has serious medication side effects and should be avoided if possible. Posaconazole 400 mg twice daily has been effective in refractory esophageal candidiasis as well. [5][6][7] (A1)

One may also use caspofungin as it is preferred over amphotericin.

Since esophageal candidiasis is an opportunistic infection and most often seen in immunocompromised persons, the cause of the immunosuppression should be diagnosed and treated as well.[8][9][10](A1)

Patients who are immunosuppressed and have symptoms of odynophagia or dysphagia can empirically be treated with a 14-21 day course of antifungal therapy. If no improvement in symptoms is seen after 72 hours of treatment then upper endoscopy should be performed.[11] (A1)

The dose of the azole agents does need modification in patients with renal insufficiency.

Azoles are considered teratogenic, so in pregnant patients with esophageal candidiasis, Amphotericin B is preferred.

Differential Diagnosis

Other common causes of esophagitis are as follows:[1][12][13]

- Cytomegalovirus

- Herpes simplex virus

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Pill-induced esophagitis

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Radiation esophagitis

- Bacterial esophagitis (from Lactobacillus, B-hemolytic streptococci, Cryptosporidium, Pneumocystis carinii, Mycobacterium avium complex, Nocardia, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Leishmania donovani)

Prognosis

There are no specific papers discussing the prognosis of esophageal candidiasis. It is usually treated successfully with antifungal agents. Resistant and refractory infections can occur and may require alternative agents for treatment or long term antifungal prophylaxis to reduce recurrence.[7]

Complications

Esophageal candidiasis complications include esophageal ulcerations with potential for esophageal perforation and upper gastrointestinal bleeding, weight loss, malnourishment, sepsis, candidemia, esophageal stricture, fistula formation into a bronchial tree.[14][15][16][2]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

When patients are treated with azoles, there is a risk of liver damage; hence liver function tests should be regularly monitored. Long term treatment is rarely required except in patients who are immunosuppressed.

Consultations

Since upper endoscopy is a requirement for tissue sampling or brushing of the candida plaques in the esophagus, a gastroenterologist or general surgeon would be required to perform the procedure. A pathologist will make the diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis through histologic staining. Infectious disease specialists may be needed to help with treating refractory or recurrent esophageal candidiasis. Infectious disease physicians can also manage the patient's treatment for concomitant HIV which is causing their immunosuppression. Hematology/oncology specialists may also be consulted to manage patients with immunosuppression or manage chemotherapy medications which are causing immunosuppression.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Since candida is a normal oral flora that proliferates in immunocompromised states of health, one way of decreasing the risk of esophageal candidiasis is to improve health conditions that can cause immunosuppression. Decreasing the use of antibiotics, systemic steroids, and the proper use of inhaled steroids can also be used to limit the risk of esophageal candidiasis. Prophylactic fluconazole may be necessary for patients that have recurrent infections.[2]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

There may be some coordinated care between physicians in regard to interprofessional communications when it comes to dealing with esophageal candidiasis. A gastroenterologist or general surgeon may perform the upper endoscopy required for biopsies and brushings of the esophagus. A pathologist will confirm the diagnosis through histology. Most healthcare professionals feel comfortable treating esophageal candidiasis. The primary care provider including the pharmacist must emphasize medication compliance for a cure. In addition, the clinicians should monitor liver function and adjust the dose according to renal insufficiency. The infectious disease nurse must ensure that HIV patients on HAART otherwise the treatment is prolonged and often ineffective. If patients have recurrent infections or infections refractory to treatment, then an infectious disease specialist may help. Pharmacists can also help with dosing guidelines. Also, coordinating care with other specialists may be important when managing the causes of immunosuppression. These patients need long term monitoring to ensure cure. Open communication between the team members is vital to ensure good outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rosołowski M, Kierzkiewicz M. Etiology, diagnosis and treatment of infectious esophagitis. Przeglad gastroenterologiczny. 2013:8(6):333-7. doi: 10.5114/pg.2013.39914. Epub 2013 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 24868280]

Alsomali MI, Arnold MA, Frankel WL, Graham RP, Hart PA, Lam-Himlin DM, Naini BV, Voltaggio L, Arnold CA. Challenges to "Classic" Esophageal Candidiasis: Looks Are Usually Deceiving. American journal of clinical pathology. 2017 Jan 1:147(1):33-42. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqw210. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28158394]

Takahashi Y,Nagata N,Shimbo T,Nishijima T,Watanabe K,Aoki T,Sekine K,Okubo H,Watanabe K,Sakurai T,Yokoi C,Kobayakawa M,Yazaki H,Teruya K,Gatanaga H,Kikuchi Y,Mine S,Igari T,Takahashi Y,Mimori A,Oka S,Akiyama J,Uemura N, Long-Term Trends in Esophageal Candidiasis Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors with or without HIV Infection: Lessons from an Endoscopic Study of 80,219 Patients. PloS one. 2015; [PubMed PMID: 26208220]

Choi JH, Lee CG, Lim YJ, Kang HW, Lim CY, Choi JS. Prevalence and risk factors of esophageal candidiasis in healthy individuals: a single center experience in Korea. Yonsei medical journal. 2013 Jan 1:54(1):160-5. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.1.160. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23225813]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWalsh TJ, Hamilton SR, Belitsos N. Esophageal candidiasis. Managing an increasingly prevalent infection. Postgraduate medicine. 1988 Aug:84(2):193-6, 201-5 [PubMed PMID: 3041396]

Klotz SA. Oropharyngeal candidiasis: a new treatment option. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006 Apr 15:42(8):1187-8 [PubMed PMID: 16575740]

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Schuster MG, Vazquez JA, Walsh TJ, Zaoutis TE, Sobel JD. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016 Feb 15:62(4):e1-50. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ933. Epub 2015 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 26679628]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSkiest DJ, Vazquez JA, Anstead GM, Graybill JR, Reynes J, Ward D, Hare R, Boparai N, Isaacs R. Posaconazole for the treatment of azole-refractory oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis in subjects with HIV infection. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007 Feb 15:44(4):607-14 [PubMed PMID: 17243069]

Lake DE, Kunzweiler J, Beer M, Buell DN, Islam MZ. Fluconazole versus amphotericin B in the treatment of esophageal candidiasis in cancer patients. Chemotherapy. 1996 Jul-Aug:42(4):308-14 [PubMed PMID: 8804799]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencede Wet NT, Bester AJ, Viljoen JJ, Filho F, Suleiman JM, Ticona E, Llanos EA, Fisco C, Lau W, Buell D. A randomized, double blind, comparative trial of micafungin (FK463) vs. fluconazole for the treatment of oesophageal candidiasis. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2005 Apr 1:21(7):899-907 [PubMed PMID: 15801925]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBenson CA, Kaplan JE, Masur H, Pau A, Holmes KK, CDC, National Institutes of Health, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treating opportunistic infections among HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association/Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2004 Dec 17:53(RR-15):1-112 [PubMed PMID: 15841069]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAntunes C, Sharma A. Esophagitis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28723041]

Geagea A, Cellier C. Scope of drug-induced, infectious and allergic esophageal injury. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2008 Jul:24(4):496-501. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328304de94. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18622166]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOstrosky-Zeichner L, Rex JH, Bennett J, Kullberg BJ. Deeply invasive candidiasis. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2002 Dec:16(4):821-35 [PubMed PMID: 12512183]

Lee KJ, Choi SJ, Kim WS, Park SS, Moon JS, Ko JS. Esophageal Stricture Secondary to Candidiasis in a Child with Glycogen Storage Disease 1b. Pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology & nutrition. 2016 Mar:19(1):71-5. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2016.19.1.71. Epub 2016 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 27066451]

Aghdam MR, Sund S. Invasive Esophageal Candidiasis with Chronic Mediastinal Abscess and Fatal Pneumomediastinum. The American journal of case reports. 2016 Jul 8:17():466-71 [PubMed PMID: 27389822]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence