Introduction

The Eustachian tube is named after the Italian anatomist, Bartolomeo Eustachi, who observed that it was a canal that connected the nasopharynx to the middle ear. The Eustachian tube is also known as the pharyngotympanic tube or the auditory tube.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

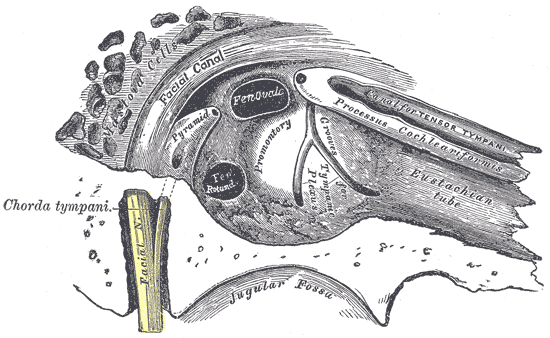

The Eustachian tube plays a role in equalization, oxygenation, and drainage of the tympanic cavity in the middle ear. More specifically, the Eustachian tube permits equalization of pressure in the middle ear with respect to ambient pressure. In doing so, the Eustachian tube allows for regulation of the pressure across the tympanic membrane. It thus influences the tension in this structure and the attached ossicles, and in this way indirectly affects the effectiveness of sound wave transmission. It is believed that the Eustachian tube also may be involved in sound transformation through reverberation phenomena. Patency of the tube allows for air exchange in the tympanic cavity to replenish oxygen to the middle ear, in addition to providing an outlet for mucus and other fluid from the middle ear.[3][4]

Partly a hollow tube in bone and partly a potential space in fibroelastic cartilage, the Eustachian tube is normally closed, as its proximal walls are collapsed. These can be actively pulled apart to open the tube with the help of accessory muscles or passively pushed apart by air exiting or entering the middle ear under pressure. The active opening of the Eustachian tube to relieve positive or negative pressure in the middle ear commonly is called “clearing the ear.”

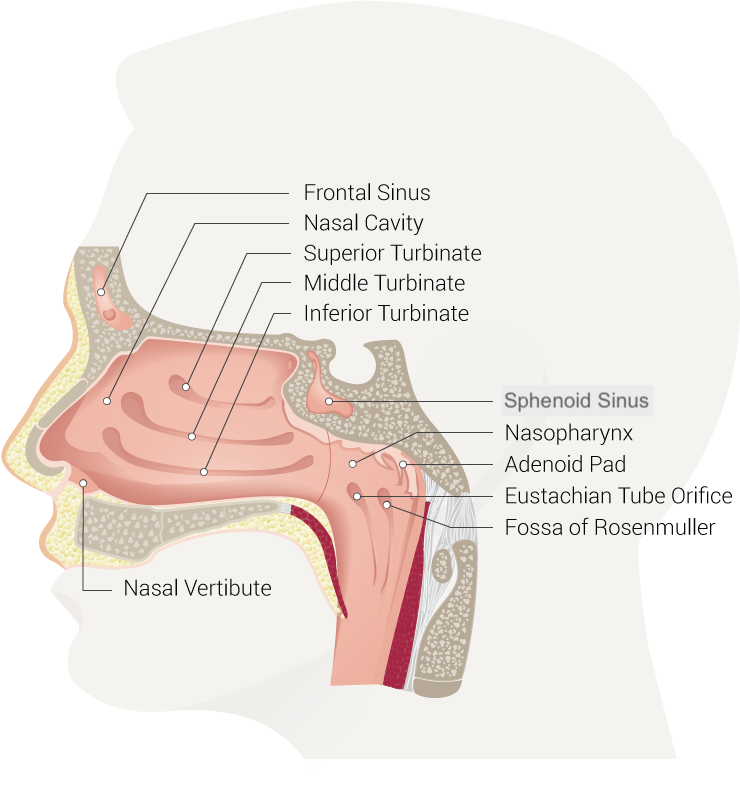

The Eustachian tube is located in the para-pharyngeal space and is closely linked to the infratemporal fossa. The Eustachian tube continues from the front wall of the middle ear to the sidewall of the nasopharynx, progressing along the posterior edge of the medial pterygoid plate. It then proceeds forward, downward, and medially, to form a 45-degree angle to the sagittal plane, and about a 30-degree angle to the horizontal plane.

The discontinuous opening of the pharyngeal ostium in the nasopharynx causes peristaltic-like movements that may be due to the visco-elastic features of the tubular structure of the cartilage.

Embryology

The Eustachian tube partially originates from the first pharyngeal pouch and extends as tubotympanic recess. After contact with the outer ear canal, mesoderm between 2 canals forms the tympanic membrane; this expands to form the tympanic recess. The stalk of the recess forms the Eustachian tube. The skeletal elements have two parts, the boney lateral portion that arises from the anterior wall of the auditory bulla and the cartilage portion that covers the dorsal region along the length of the tube.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood is supplied to the Eustachian tube by several arteries of the external carotid, including the ascending pharyngeal branch and two branches of the maxillary artery, the middle meningeal artery, and the artery of the pterygoid canal. Venous returns drain into the pterygoid venous plexus, and lymphatics drain into the retropharyngeal lymph nodes.

Nerves

Motor innervation to the muscle attachments of the Eustachian tube is provided by the pharyngeal plexus of the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) and the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). Specifically, the levator veli palatini and salpingopharyngeus muscles are innervated by cranial nerve X, and the tensor tympani and tensor veli palatini muscles are supplied by the mandibular branch of cranial nerve V. Sensory innervation to the Eustachian tube, middle ear, and the trigeminal nerve governs pharynx.

The pharyngeal ostium is affected by a pharyngeal branch of the maxillary nerve, the spine from the cartilage branch area arising from the mandibular nerve, while the osseous portion of the bone is affected by the tympanic plexus arising from the glossopharyngeal nerve.[5]

Muscles

There are 6 muscles recognized as having an active role in the functions of the tube: tensor tympani, salpingopharyngeus; tensor veli palatini; levator veli palatini; lateral and medial pterygoids. The tensor muscle of the soft palate (TVP) not only functions to open up the lumen of the Eustachian tube, but it also contributes to mastication as it is actively involved in the process of phonation, swallowing, chewing. During these motions, the ET is oriented inwards.[6][7]

The TVP is made of an external and medial portion, the first of which originates from the navicular fossa, the lateral aspect of the sphenoid bone/sulcus, and the tensor tympani muscle.

The medial segment is derived from the middle third of the posteromedial wall of the tube that is mostly cartilage; the two segments then migrate inferiorly and converge on the pterygoid hamulus forming a strong tendon that curves around the hamulus and anchors directly into the soft palate as the palatine aponeurosis. The TVP operates in combination with the tensor tympani muscle (TT), and they both share similar nerve innervation. Its lateral surface directly contacts the surface of the anterior superior medial pterygoid muscle. Its strength declines with age and a change in its force vector and a reduction in its range of motion.

The elevator of the soft palate (LVPM) is cylindrical and traverses the space just underneath the ET, entering into the cartilaginous portion. Here it forms a sling with fixed insertion points between the midline of the soft palate and the petrous apex of the temporal bone; it sits posteriorly and medially to TPV, with anatomical continuity. Its actions on the tube are not in agreement in the literature where it can be found to have an opening and closing role. The vagus nerve innervates it.

The tensor tympani (TT) is a thin muscle positioned outside the middle ear and along the tube. It is anchored to the sphenoid bone and the bony segment of the ET. distally, the tendon anchors onto the malleolus in the superior and middle segment of the ear, involving the stapedius muscle and stirrup. Its contraction assists and occurs in conjunction with the TVP, while at the same time, placing tension on the malleolus to muffle the vibrations in the eardrum during mastication and swallowing.

The TT and TVP are connected via a fascial link that receives innervation by the mandibular branch of the fifth cranial nerve (trigeminal). The salpingopharyngeal (SP) is one of the straight internal pharyngeal muscles that contribute to the process of swallowing mechanism; it receives innervation from a branch of the 10th cranial nerve (vagus). When the SP and the other 2 internal longitudinal muscles (stylopharyngeus and palatopharyngeus) contract, this results in shortening of the pharynx and laryngeal elevation. The SP is thinly spread over the cartilage segment of the ET. The muscle is small and thin so that it can easily cross the pharynx and at the same time have an anatomical relationship with the palatine tonsil. As of now, there is a scarcity of information on the exact physiological function of the SP, but most anatomists believe that it only plays a minor role in the opening of the ET.

The lateral (external) pterygoid muscle (LP) and the medial (internal) pterygoid muscle (PM) are a group of muscles involved in mastication and function of the middle ear. The LP is created by the 2 muscle heads (bellies), lower and upper.

The literature states that there is also a contribution from 2 other muscles; the pterygospinous and the pterygoideus proprius. The upper belly starts in the infratemporal surface and the crest of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone, while the inferior belly evolves from the lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid plane; both muscle segments have a horizontal orientation posterolaterally. The muscle bellies are anchored in the pterygoid fovea muscle just underneath the condylar process of the mandible. However, the superior belly of the LP does anchor to the articular disc of the temporomandibular joint and plays a role in jaw movements.

The PM is found below the LP. The PM is thinner and quadrangular in shape; it traverses the inferior segment of the infratemporal fossa. The PM has 2 muscle bellies, one shallow and one deep. The deep belly starts laterally to the maxillary tuberosity and the palatine pyramidal process, crossing just underneath the inferior belly of the LP, while the shallow belly is wider and arises from the medial surface of the lateral pterygoid plate and the pterygoid fossa. This muscle courses much deeper to the inferior segment of the LP.

Both segments of the PM travel laterally and inferiorly to anchor to the rear and inferior medial surface of the angle of the mandible. The mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve innervates the PM. An additional function of these dual masticatory muscles is to enable peristaltic movement of the tube, in cooperative interaction with the LVPM and TVP, during the process of swallowing, mimicking the same active motions of the LP, even when there is no swallowing, allowing the tube to open. Their intervention changes the shape of the tube, which becomes more convex, allowing the muscles that act directly on the tube to provide a greater force. The PM is also useful, in particular, because it may act as a fulcrum so that the musculature of the tube acts as a more efficient vector.

Physiologic Variants

Anatomic and physiologic variations within the Eustachian tube may be causative factors in cases of Eustachian tube dysfunction. Manifestations include difficulty in opening the tube and problems with patency. These variations include narrower tube diameter; flaccidity of the cartilaginous portion of the tube or surrounding tissues; and mucosal hypertrophy of the tube lining, which leads to excess mucus production and clogging.

Surgical Considerations

The structure of the Eustachian tube is made up of 2 anatomically distinct parts covered by the mucous membrane: a bony component and a cartilaginous component. The bony component courses through the petrous part of the temporal bone and represents one-third (12 millimeters) of the tube's length. The Eustachian tube follows a straight course and slopes down posteroanteriorly and lateromedially at an angle of approximately 35 degrees in adults. The tube begins with an aperture on the anterior, or carotid, wall of the middle ear at the junction of the petrous and squamous constituents of the temporal bone and opens into the tympanic cavity, the walls of which are continuous with the middle ear. Its other end opens into the lateral wall of the nasopharynx, roughly at the level of the inferior turbinate. The Eustachian tube has a diameter of approximately 3 millimeters and is widest at its two ends and narrowest at its isthmus, which typically is found in the cartilaginous portion. It normally is closed due to pressure from adjacent Ostmann fat pads. The Eustachian tube is lined with ciliated epithelium, which sweeps mucus away from the middle ear in the direction of the nasopharynx.[8][9]

Clinical Significance

In children, the Eustachian tube’s course is more horizontal than in adults (10 degrees concerning the horizontal versus 35 degrees in adults). This is believed to be a contributing factor in the development of acute otitis media in children due to impaired middle ear drainage and even reflux of nasopharyngeal contents into the middle ear through the Eustachian tube. Mucus cannot drain as readily with the smaller slope.

As a pathway connecting the middle ear to the pharynx, the Eustachian tube serves a dual purpose as an entrance and an exit to the middle ear. Gas is not the only substance that can be exchanged via this channel. Pharyngeal contents, most notably phlegm from the nasal passages and nasopharyngeal secretions, constitute liquid media that may be drawn or pushed inside the middle ear through the Eustachian tube and constitute a source of infectious organisms. Conversely, the Eustachian tube is also the principal outlet for middle ear effusions. In cases of obstruction, pressure may build up within the middle ear, leading to rupture of the tympanic membrane. This may occur in barotrauma or perforated otitis media.

Prostheses exist to facilitate Eustachian tube patency. Usually, these only are useful in the short term, as mucus rapidly plugs them.

Eustachian tube dysfunction is not limited to obstruction. It also can involve intermittent opening or patulousness of the tube. In this case, patients may complain of autophony, which is characterized by hearing their chewing and speaking unusually loudly.[4]

Other Issues

Some individuals can master active opening of their Eustachian tubes while others struggle. Difficulty in opening the Eustachian tube, and thus equalizing air pressure in the middle ear, may predispose the patient to ear pain with abrupt altitude changes. In general, air more readily escapes the middle ear than enters it under pressure. For this reason, those who fly in an airplane tend to experience more severe symptoms when going from low to high ambient pressure (landing) than from high to low ambient pressure (taking off). The Valsalva maneuver can help in opening the Eustachian tube by insufflating air inside of it. Divers must master this technique of opening their Eustachian tubes to equalize while underwater. Similar to flying, divers must more frequently perform the Valsalva maneuver when descending into greater depth (low to high ambient pressure) than ascending to the surface (high to low ambient pressure).

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kobayashi T, Morita M, Yoshioka S, Mizuta K, Ohta S, Kikuchi T, Hayashi T, Kaneko A, Yamaguchi N, Hashimoto S, Kojima H, Murakami S, Takahashi H. Diagnostic criteria for Patulous Eustachian Tube: A proposal by the Japan Otological Society. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2018 Feb:45(1):1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.09.017. Epub 2017 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 29153260]

Jufas N, Rubini A, Soloperto D, Alnoury M, Tarabichi M, Marchioni D, Patel N. The protympanum, protiniculum and subtensor recess: an endoscopic morphological anatomy study. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2018 Jun:132(6):489-492. doi: 10.1017/S0022215118000464. Epub 2018 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 29888690]

Savenko IV, Boboshko MY. [The patulous Eustachian tube syndrome: the current state-of-the-art and an original clinical observation. Second communication]. Vestnik otorinolaringologii. 2018:83(3):77-81. doi: 10.17116/otorino201883377. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29953063]

Tysome JR, Sudhoff H. The Role of the Eustachian Tube in Middle Ear Disease. Advances in oto-rhino-laryngology. 2018:81():146-152. doi: 10.1159/000485581. Epub 2018 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 29794454]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFalcon RT, Rivera-Serrano CM, Miranda JF, Prevedello DM, Snyderman CH, Kassam AB, Carrau RL. Endoscopic endonasal dissection of the infratemporal fossa: Anatomic relationships and importance of eustachian tube in the endoscopic skull base surgery. The Laryngoscope. 2011 Jan:121(1):31-41. doi: 10.1002/lary.21341. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21181982]

Okada R, Muro S, Eguchi K, Yagi K, Nasu H, Yamaguchi K, Miwa K, Akita K. The extended bundle of the tensor veli palatini: Anatomic consideration of the dilating mechanism of the Eustachian tube. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2018 Apr:45(2):265-272. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.05.014. Epub 2017 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 28625531]

Liu CL, Hsu NI, Shen PH. Endoscopic endonasal nasopharyngectomy: tensor veli palatine muscle as a landmark for the parapharyngeal internal carotid artery. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2017 Jun:7(6):624-628. doi: 10.1002/alr.21921. Epub 2017 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 28383178]

Brown EC, Lucke-Wold B, Cetas JS, Dogan A, Gupta S, Hullar TE, Smith TL, Ciporen JN. Surgical Parameters for Minimally Invasive Trans-Eustachian Tube CSF Leak Repair: A Cadaveric Study and Literature Review. World neurosurgery. 2019 Feb:122():e121-e129. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.123. Epub 2018 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 30266704]

Sun X, Yan B, Truong HQ, Borghei-Razavi H, Snyderman CH, Fernandez-Miranda JC. A Comparative Analysis of Endoscopic-Assisted Transoral and Transnasal Approaches to Parapharyngeal Space: A Cadaveric Study. Journal of neurological surgery. Part B, Skull base. 2018 Jun:79(3):229-240. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606551. Epub 2017 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 29765820]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence